Deniz Kuru

Goethe-Universität Frankfurt

This study aims to provide an exploratory analysis of Global IR, by pointing to its novelty as a tool for expanding our disciplinary frameworks, and furthermore, by connecting it to the quite simultaneously emerging field of Global Intellectual History. Such an approach enables a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics that have led to an overall focus on the “global.” The first part elaborates how the idea of Global IR has emerged as a novel disciplinary tool, and pinpoints the various meanings it has gained. Second, the focus shifts to the novel scholarship of Global Intellectual History. Elaborating this field’s most significant contributions will make it possible to emphasize the useful role it can play in furthering the idea of Global IR in a more historically (self-)conscious manner. The importance of this approach will also be underlined by referring to the increased relevance of disciplinary critique in the specific context of IR-history (dis)connections. The third part turns its attention to various cases (as vignettes) that aim to visualize how connecting these two new “Globals” (i.e. Global IR and Global Intellectual History) could provide the discipline of IR with a better means to deal with the past and present of global politics. Therefore, by explaining the conceptual, ideational, and geo-epistemological divergences and commonalities whose roots can be more concretely studied through a broader engagement with Global Intellectual History, the article clarifies the advantages of this “inter-Global” connection. It concludes by discussing the value of Global IR in terms of its potential role for broadening the discipline not just in ways that are more (IR-)introspective but also in its bridge-building capacity to other fields with similar concerns, extending to Global Intellectual History and beyond, and provides a brief list of initial suggestions.

1. Introduction

In recent years, there seems to have emerged a new turn in the discipline of International Relations (IR), but one that does not come up with another theoretical perspective to be employed.[1] Rather, it concerns the very disciplinary foundations of IR, going even beyond its debates on philosophy of science,[2] or ontology.[3] This novelty concerns an overwhelming interest in overcoming the Western-centric nature of the discipline. However, it is not necessarily overlapping with the postcolonial approaches in IR that have been the usual source when one encounters this type of critique. The recent calls for a “Global IR” provide a broader, and at times more mainstream-supported attack on the past and present of the discipline, calling for making geo-epistemological and also geo-ontological revisions in our way of looking at the world, and hence at IR. This new perspective promises a different outlook within our disciplinary enterprise, and mostly in a way that recognizes the actual changes in the domain of world politics, or as Buzan and Acharya recently stated, in the world of international relations (“ir” without upper scale letters).[4]

This study aims to provide a dual structure in order to address the issue of a possible dialogue between the emerging Global IR and the similarly novel approach in the discipline of History, namely Global Intellectual History. The article first elaborates the emergence of the idea of Global IR, underlining its definitional variations. In this regard, I also provide a quantitative study on the usage of the concept of Global IR (but also Global International Relations), explaining its growing popularity in the aftermath of Amitav Acharya’s presidential speech at the International Studies Association (ISA), which later became an article in 2014 in its flagship journal International Studies Quarterly (ISQ).[5] Finally, the main features of Global IR are explored via a close engagement with Acharya and Buzan’s most recent take on this quest for globalizing the discipline.[6] This serves also as a connection to the discussion of Global History, and more specifically Global Intellectual History, as tools at the disposal of the Global IR project.

In the second part of the study, the emphasis shifts to the relevance of a new historiographical approach, one that is located at the intersection of Global History and Intellectual History. By examining the significance of Global Intellectual History, I aim at showing the multiple promises of this field of research in the realization of Global IR. First, there follows an examination of Global History and the consequent emergence of Global Intellectual History. Subsequently, I underline the usefulness of this approach for Global IR by providing a number of vignettes that point to potential benefits of this type of research. Later, the study turns its attention to a possible triangulation effort in the context of interdisciplinary cooperation. In this regard, I pinpoint the importance of combining Global IR and Global Intellectual History with the insights of (Global/International) Historical Sociology in order to connect the study of ideas to their institutional and structural dimensions. Here also lies a certain promise for advancing IR among other social sciences. The conclusion, in turn, considers the prospects of these connections, especially between Global IR and Global Intellectual History and provides a list of to-dos which could further the project of Global IR.

2. Global IR for the Mainstream – Redefinition and Popularization

There are a number of varying definitions for the idea/approach of Global IR. However, interest in it has witnessed a dramatic rise in the last couple of years. Before approaching the various engagements within IR, I propose to focus on Acharya’s 2014 piece and point to its leading role in widening the usage of the concept, making it thereby a popular and more familiar perspective in IR scholarship. Based on this, I offer a brief discussion on varying understandings of Global IR, returning consequently to the approach put forward by Acharya (and Buzan). This prepares the way for the later parts on Global Intellectual History.

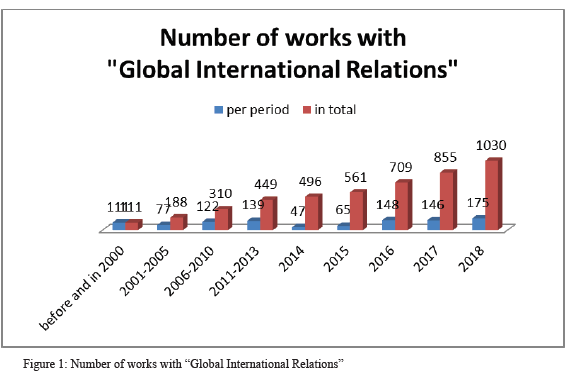

In order to check whether Acharya’s ISA presidential address, which became an ISQ piece in 2014, had a major impact in making the concept a popular one for IR scholars around the globe, I looked at two widely used sources: Google Scholar and Web of Science. The analysis sought to gauge for the temporal frequency of the usage of both “Global International Relations” and “Global IR.” In this framework, it became clear that the former has been used also in broader senses, e.g. the wider structure of world politics, etc. This resulted in more than 1000 texts for the period until 2019. Of this, some 100 were found in the years up to and including 2000, whereas more than 300 new texts were published up to and including 2013. Afterwards, I focused on individual years, and found a visible tendency of continuous increase (from some 47 in 2014 to 175 alone in 2018). This means that even the more diversely employed concept of “Global International Relations” (which in many individual instances was in fact employed as global international relations) still points to the growing influence of the idea of a disciplinary “Global International Relations” from 2014 on (see figure 1).

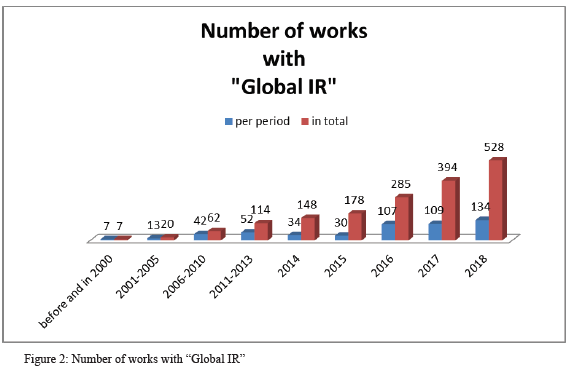

In the more specific instance of “Global IR” (where the search was secured by additionally checking for “international relations” in order to detach it from similar but unrelated usages of the shortening “IR”), the results emphasized in an even more evident manner the popularity of the concept starting in 2014. Prior to 2001, it was used in only seven works, and there were in total merely some 100 pieces before 2014. In that year there followed some 30 new publications, only to increase to circa 110 in 2017 and 134 in the following year. The total has risen from some 150 in 2014 to more than 500 four years later (see figure 2).

An analysis of the Web of Science records provides us with an even clearer picture. There is just one article referring to “Global International Relations” prior to Acharya’s 2014 piece. On the other hand, in its aftermath, there would be already 16 works using this concept, showing that his article has played the role of a popularizing factor for this rather recent labelling. When gauging for the impact of “Global IR” in a separate manner, one finds 29 studies in the area of IR, with only two of them preceding Acharya’s article. This again underlines the effect his ISA speech and ISQ piece seem to have had on the broader employment of this concept.

In addition to these figures, the citation numbers of Acharya’s article also demonstrate its significant role, with some 250 by Google Scholar and close to 90 by Web of Science.[7] These findings suggest two important insights. First, Acharya’s piece has played a path-breaking role in making the concept of “Global International Relations”/“Global IR” a freshly popular label for the wider IR community. Second, this novelty is reflected in the concept’s broader usage within the last couple of years.[8] In light of this, it becomes useful to turn our attention to the different ways in which Global IR can be understood and the changes it could implement for the discipline. Such a broader overview can demonstrate both the multiple meanings Global IR has taken on and the greater relevance of the approach developed by Acharya (and Buzan, with whom he frequently cooperates in this area), as related to this preceding analysis.

Although Acharya’s article has been shown to play a major role in popularizing “Global IR,” we still need to be careful when approaching this concept, for its usage has not seen a single path commonly followed by all. In this regard, I want to explain certain divergences that emerge in its employment, and clarify the reasons for such differences among IR scholars. First, it is important to acknowledge the role played by postcolonialist scholars[9] and later decolonial approaches[10] for overcoming the Western-centric nature and structure of the discipline.[11] Their distinct call is itself not of a very old origin, having started to significantly impact IR in the 1990s. Developments in other fields, most famously Edward Said’s study on Orientalism and Foucauldian approaches had a visible influence in this context. The main theme of postcolonial scholars has been to call for a more inclusive IR that would, through this less Western-centric understanding of its role and contents, become a better tool for understanding more than just the Western world and its impact. It would also offer an explanation about how the broader world and its “international relations” function. In this framework, a specific focus was on concepts like the Global South, with at times has focused largely on differences between the North and the South. The time was seen as having arrived for the latter to have finally (or once again) a say in world politics and in its study. Decolonial contributions later enriched this approach by further emphasizing the problematic nature not only of the Western dominance in knowledge production but also the multiple ways in which this knowledge was assumed to be of universal validity, further strengthened by the power political hegemony of Western powers.[12] In these analyses, there exists an urgent need for overcoming these obstacles in order to pave the way for the non-Western sources of knowledge and their promotion.

Alternatively, one should also take into account the various scholarly communities who consider the necessity of widening IR by taking in insights from local/national/regional IR scholarship. While this has also been partially a quest of earlier postcolonial scholars, the limits of such an approach have led to multiple debates on the actual ways of undertaking this task. On the one hand, there exist scholars who underline the structural constraints of such contributions within IR, pointing to non-Western scholarship’s failure to come up necessarily with original contributions, mostly due to the perceived manners of reproducing earlier Western-derived knowledge.[13] On the other hand, there are scholars who insist on the benefits of a sustainable focus on the insights to be gained by turning our attention more closely to homegrown theorizing in IR, with its inclusion of non-Western sources of ideational and material backgrounds.[14]

A historically more self-conscious approach would require us to remember the days of the interwar International Studies Conference (ISC) that held regular meetings in the 1930s.[15] Its scholarly and institutional membership structures as well as congresses used to bring academics and representatives of earlier think tanks and philanthropic foundations together, and without the hermetically sealed off disciplinary structure that we witness today: political scientists, sociologists, historians, legal scholars, and others were involved in what we could call Global Studies.[16] Therefore, following such a path would lead us to think of calls for “Global IR” as a move that pushes the discipline closer to its historical roots. In this sense, the ISC and interwar IR are not that distant from this call, serving partially as proto-Global IR, both with their global membership structure and international participation (beyond the West, but not necessarily beyond the North) in its annual gatherings.

Another way to engage with the recent “global turn” in IR could lead us to perceive, at least some of the usages of the concept, as part of the discipline’s often witnessed tendency for fads and fashions. This signifies an inclination for using concepts without much careful analytical consideration of their specific and broader meaning. In the specific case of “global IR,” where it is now possible to observe a very significant increase in the frequency with which this concept is employed (as discussed above), one should take care not to miss the forest for the trees. Not all uses of the concept refer to the same idea. Therefore, at a time when even a recent textbook edition has a subsection on “global IR” discussing, respectively, IR theories in China, India, Latin America, the Islamic world, and Africa, one needs to differentiate between these varying associations of “Global IR.”[17] Regional specifications of IR do not necessarily end up bringing about a globalized IR, but can indeed act as further mechanisms of parochialism, especially if regional compartmentalization does not add up to a more globalized IR.

At this juncture, let us shift our focus to Acharya’s call for a “Global IR” and briefly elaborate on his understanding of what it stands for. His interest in broadening IR does not derive just from his period as ISA president, but has earlier origins in his work on the relevance of non-Western IR theories, including his co-authored article-later-turned-into-book (with Buzan) where they tried to answer the question “Why is there no non-Western international relations theory.”[18] Later on, this quest for broadening the knowledge sources of IR went beyond a narrow focus on theories, with his interest extending towards the direction of globalizing IR. This meant making the discipline more familiar and inclusive with broader engagement of processes that had origins, changes, modifications, or renovations in non-core regions of IR.

Now we have a more developed analysis by Acharya and Buzan that encompasses virtually all the history of IR and “ir”, based on the assumed centenary of the discipline’s 1919 post-World War I foundation, and published on this (mythical) 100th anniversary. In their The Making of Global International Relations – Origins and Evolution of IR at its Centenary,[19] the two scholars employ a heavily externalist account of disciplinary history,[20] one that discusses the prospects of a Global IR at times of an emerging post-Western world. It is in this book that one finds the most up-to-date conceptualization of Global IR within the frameworks employed by Acharya and Buzan. For the authors, their approach’s distinction from the postcolonial approaches is quite clear, with the former seen as being open for both mainstream theories and postcolonial or critical approaches. Global IR, for the two scholars, is, in consequence, not to be interpreted as a rejection of mainstream theories, a point they put forward very explicitly.[21]

The question that necessitates an answer relates to their own definition of what the aim and the contents of Global IR are to be. According to Acharya and Buzan, it should not be seen as “a theory or method,” but rather to be understood as “more a framework of inquiry and analysis of international relations in all its diversity, especially with due recognition of the experiences, voices and agency of the Non-Western peoples, societies and states,” actors which are seen as having remained largely overlooked by IR.[22] In this regard, their approach to Global IR emerges like a much needed disciplinary aggiornamento, which refers to the need for updating the discipline and its frameworks of study, theorizing and teaching in a rapidly post-Westernizing world.

At the same time, theirs is a certain type of via media approach, not atypical in IR scholarship.[23] Its positioning seems to accept not a few of the postcolonial assumptions, trying, however to find a less critical location; one which would make Global IR more suitable to mainstream scholars. In an interesting move, the two authors emphasize Global IR as an approach that does not try to challenge “any particular theory” by offering “an alternative.”[24] Rather, their goal is for Global IR to make the discipline “truly global” by offering means of overcoming its “mainly West- and indeed Anglosphere-centric” nature.[25]

They relate the concept of Global IR to seven dimensions around which it could be structured. As the consequent discussion is based on some of these elements, a brief exploration of them is of much importance. First, the concept emerges from what they call a pluralistic universalism, with the concomitant readiness for “recognizing and respecting the diversity of humankind.” It is “grounded in world history,” making it broader than the usual focuses on “Greco-Roman, European or US history” that structure and generate much of IR scholarship. Third, extant theories and methods are to be subsumed, not supplanted. Fourth, “the study of regions, regionalisms, and Area Studies” are to be integrated into the discipline. Also, it rejects those frameworks that are grounded “on national or cultural exceptionalism.” Furthermore, there is not just “the state and material power,” but more than one form of agency playing a role in world politics. Lastly, globalization is not seen as merely influencing processes of “the diffusion of wealth, power and cultural authority,” considering also the role of interdependence and “shared fates”.[26]

Later on, the authors also provide a list of items that should present the research agenda of Global IR. These include “discovering new patterns, theories and methods from world histories,” dealing with recent global power shifts that relate to the demise of “Western dominance,” engaging with “regional worlds” with all their interconnections, integrative employment of IR and “Area Studies knowledge,” as well as “[e]xamining how ideas and norms circulate between global and local levels,” and inter-civilisational processes of “mutual learning.” At the same time, they tie Global IR to IR theorizing by pointing to certain sources for a more global IR theory, seeing not only in contemporary Critical IR, postcolonial leaders or the practices of world politics such sources, but also in classical traditions, and in the thought of historical figures.[27]

Acharya and Buzan take care to refrain from constraining Global IR to becoming a spatializing or totalizing concept, disconnecting it, respectively from a mere insistence on being geographically all encompassing, or just inclusive of all issue areas. The “global” presents for them at the same time “an intersubjective notion” with all the concomitant references to “interdependence and linkages between actors … and areas”. The two scholars recognize the significance, in this context, of paying special attention to “the origins and meanings of concepts and practices” as “their autonomous, comparative and connected histories and manifestations” matter a lot.[28]

Based on Acharya and Buzan’s understanding of the “global”, their explorations of Global IR’s dimensions, its research agenda, and the elaboration of “possible sources of theorizing across regions,” there emerges a distinct framework. It is these features listed above that provide in turn the basis on which to connect the discussion on Global IR to this article’s second focal point, to wit, Global Intellectual History. As is visible in Acharya and Buzan’s emphases, Global IR offers a way of tackling the new world politics of a post-Western world, without necessarily creating hermetic separations between the West and the non-West. Indeed, it is the artificiality of such an approach against which the authors explicitly warn us already at the very start of their book.[29]

In the aspects of Global IR that they explored, and that I emphasized above, there are certain ones which lead us to the direction of Global History, and more specifically Global Intellectual History. Let us now turn to these references, explain the only implicitly defined role for History in these new functions of Global IR, and discuss, in the following part, in more detail how the connection between Global IR and Global Intellectual History could serve to the actual realization of the former.

The most directly tackled issue concerns the role of history. While they do not spend much time discussing History as a discipline (with even some of the index entries for “History [the academic discipline]” not in fact reflecting History as a discipline), one cannot easily overlook the focus on it. Indeed, they keep repeating the formula of world history/ies when asking for a disciplinary approach (theoretical and empirical) that would not merely base itself on Western history, or Western sources of history. Looking back at the issues of Global IR’s dimensions and research items, this emphasis is clearer. What gets repeated in these lists is the relevance of broadening not merely the empirical pool of historical observations, which are criticized for having largely remained contained to a Western(-centric) past, but also the neglected importance of following the trajectory of change that various ideas can undergo (during their global voyages across tempo-spatial variations).

On a related level, one finds in their listing of Global IR’s features and tasks the readiness to deal with the contingencies of world politics that also affect the realm of ideas. Furthermore, their calls for rejecting regional or national exceptionalisms, and looking more for inter-civilizational ties lead us even more to the direction of Global Intellectual History, which is the very historiographical domain that engages with these aspects of the past. Similarly, their invitation for more work on connections between local and global level connections, when it comes to the circulation of ideas, pushes the scholarship towards the similarly developed research agenda of this new direction in History. Acharya and Buzan’s focus on interactions, interdependencies, and linkages testifies therefore further to the impact Global (Intellectual) History can make, a point I elaborate in the consequent part, explaining simultaneously the main contributions of this novel historiographical approach.

3. Global Intellectual History for Global IR

So far, the discussion has related to the brief history of the idea of a, or for some the, “Global IR.” Besides the multiple meanings of this concept, I have also aimed to show how its usage by Acharya (and Buzan) could serve us for developing helpful ways of shifting mainstream IR to a more non-Western, to wit, more post-Western direction. In this regard, one should acknowledge that such a restructuration is not essentially a process merely limited to the domain of IR. On the contrary, it affects the broader social and human sciences. Therefore, the second part of this article will focus on a neighboring discipline, History, in order to connect its own recent “global” turn, especially in the field of Intellectual History, to IR’s present concerns for its disciplinary accommodation to a more global field of research. The differentiations and definitional variances elaborated in the first part will serve as the basis for engaging with Global Intellectual History. The consequent discussion will serve as a means of presenting tools, which would enrich the quest of Global IR in broadening our understanding of world politics, with a special contribution to come from our past.

The turn to the global has already affected History as a discipline. While some historians see in this a quest to reflect the changes in world politics, economies and societies that emerged as a result of globalization and the transformations brought about by its new dynamics,[30] others assert that a more inclusive historiographical approach does not necessitate the ontological background of globalization as we know it.[31] In the context of these intra-disciplinary debates on the origins of a global turn in History, it is useful to comprehend that the concept, similar to its IR usages, is bereft of a single definition. Stated differently, Global History has differing meanings for various scholars.[32] Nevertheless, it is possible to understand it, in a more inclusive manner, as a way of dealing with the past that tries to go beyond the 19th century product of national(istically shaped) history. Here, the focus is once again on the actors, factors, and structures that are not to be confined to the boundaries of the nation-states.[33]

Transnational dynamics and connections, waves of globalization, and their consequences as well as engagement with historical issues beyond temporal or spatial limits are among the main dimensions studied by Global History.[34] In this context, four significant vectors play a connective role: diffusion, outreach, dispersal, and expansion.[35] Such an approach also relocates Europe from its central position towards a broader but sub-global world that also includes the Middle East and the Mediterranean basin.[36] Some scholars like John Darwin define Global History as an approach that enables us to study globalization with its “very long history,” rejecting associations with just the current wave of globalization.[37] As Jürgen Osterhammel, a leading scholar of Global History suggests, one can still talk, not unlike in Global IR, of different types of Global Histories, reaching from comprehensive “histories of ‘something’”, universal histories, movement histories to competition histories of “material progress and backwardness,” network histories of expansion and connection histories with their focus on interactions and transfers.[38]

In recent years, the impact of a more global engagement with the past has also generated a major impact on a specific subfield of History, namely Intellectual History.[39] For a long time focusing on thinkers and their ideas mostly in the confines of their national frameworks, Intellectual History has at other times tended to mostly extend itself to a Western-centric analysis of the impact these ideational forces had on the “others”/“the Rest” by supposing a one-way influence that reaches the peripheries from the core.[40] However, the “global turn” has reached by now also the shores of Intellectual History, engendering in the process a novel historiographical approach: “Global Intellectual History.” Following Lovejoy, the “founding father” of the history of ideas/intellectual history, it becomes again important to underline that “ideas are the most migratory things in the world.” In this sense, this turn is for some also a return to the field’s origins.[41]

This recently elaborated way of studying the past is seen by its promoters as a means of widening the field of Intellectual History by making use of the fresh insights that come from Global History.[42] In Moyn and Sartori’s path-opening collection, the two editors emphasize that one is “at a threshold moment in the possible formation of an intellectual history extending across geographical parameters far larger than usual.”[43] However, they are also careful in not constraining themselves with a geographical framework, stating later that Global Intellectual History could also focus more on “mediators and go-betweens”[44] or “popularizers and the intellectual vulgate.”[45] In this regard, the focus is on the intermediaries, those who function as transmitters of inter-regional knowledge. Most importantly, these carriers are not merely connecting the West to the non-West, but act also in the other direction.[46] At the same time, these people process the various books, ideas, peoples’ opinions with which they interact and add (as well as subtract) their own insights to these elements.[47] Furthermore, what emerges is not merely a trans-national, and trans-border history but also one that engages with the shifts, (mis)translations, ideational overlaps and (re)formulations.[48]

Global Intellectual History aims to demonstrate the intricate ways in which our past has been marked by global(ly influential) phenomena, processes, and people. What is of utmost importance is to highlight both the globality[49] of these dimensions and the possibility of presenting a globally structured history regarding their roles and functions. It is about overcoming “scholarly parochialism” and methodological nationalism.[50] It can be either a scholarly instrument, in the sense of a more comparatively developed framework,[51] or a focus on an event from the past, which shows clear signs of globally marked patterns of interactions.[52] Beyond the question of whether the scholarly choice plays a bigger role than the “givenness” of “the global,”[53] what matters most is the explanatory enrichment that is produced by a history dealing with ideas that takes on a global dimension. That is, we need to engage with non-national terms, and not to “scal[e] up” taken-for-granted “national frameworks to the global level.”[54] Yet, it is important to stress that the exact definitional outline of the “global” is not clearly put forward, and depends in many instances on the scholar’s preference.[55]

When it comes to the distinct features of Global Intellectual History, it is useful to underline the way it focuses on the actors. Here, unlike the usual pathways of Intellectual History, the focus is on those individuals, but also groups/collectives, which find or consciously situate themselves at the intersections of an idea’s global voyage. Multiple tools are offered to study these, ranging from a focus on the ideas in their circulation, to the interactions between individuals across varying geo-epistemological contexts,[56] all the while trying to overcome certain nationalistically formed claims for ontological difference that end up reproducing various centrisms that resemble the Eurocentric problematique.[57] Furthermore, it is important to underline that in this novel setting, Western intellectual history cannot be taken for the whole of intellectual history.[58]

4. Vignettes for the dialogue of “the Globals”

The preceding section provides us with a basis upon which to develop a combination of the insights and goals of Global IR with those of Global Intellectual History. In order to do this, I offer some vignettes that should help in two aspects: demonstrating potential ways of putting Global Intellectual History to the use of Global IR, and simultaneously, illustrating disciplinary overlaps in this process. The brief elaborations will serve at the same time in further exploring the insights of Global Intellectual History within a more IR-pertinent context.

However, prior to these undertakings, a brief overview of the extant connections (literature-wise) is of much pertinence. An important early contribution is an article by Phillips discussing the significance of, more broadly, Global History, for the project of Global IR, explicitly referring to Global IR’s emphasis on a different take with history.[59] More recently, it has become possible to pinpoint works that offer studies at the crossroads of Global IR and Global Intellectual History.[60] Due to its concomitant focus on ideas and the expansion of international society, it is possible that the scholars from the (broader) British sphere would be most at ease to come with similar work in the future. Also, there is a recent article that provided a study on a 20th century Japanese intellectual, which openly asserted its aim to answer Acharya’s call for Global IR.[61] Finally, a leading international historian, Armitage offers important works in the area, but outside of the realm of Global IR.[62]

As shown in the preceding elaborations, based on the promises of Global Intellectual History, it becomes possible to connect Global IR to the former. I propose now some vignettes that would function as exploratory tools in furthering the quest for a more globally shaped IR. This way, I aim to show how recent innovations from within Global Intellectual History could help support the ongoing efforts for globalizing IR.

In Global IR literature, many discussions have focused on the relevance of finding local sources of knowledge, which could, in turn, be employed both for a better comprehension of various non-Western localities, as well as for developing distinct theories that would make use of these different insights. In this context, ideas and their carriers matter a lot. However, taking the 19th century with its wide-sweeping dynamics of change into account,[63] not to mention the dynamics of globalization associated with the last couple of decades, one needs to be careful in stating the case for local knowledge. For much of this knowledge is, to different extents, already a result of its interaction (according to different perceptions in the form of impregnation, intoxication, innovation) with Western-derived ideas. However, at the same time, studies shaped by approaches related to Global Intellectual History caution us from conceptualizing these connections as one-way processes where the non-West is merely at the receiving end. In this regard, it is important to demonstrate the role of “transnational circulation” in the development of “social thought”.[64]

For instance, let us take the case of the idea of positivism, which became a significant ideational source in the reformist and independentist movements in many regions including the Middle East in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[65] By understanding the ways in which this idea/ideology gained adherents throughout the Ottoman Empire, it becomes possible to notice both the different mechanisms that led to its variation among the local political elites and intellectuals,[66] and to explain how the intellectual journeys changed its overall ideational luggage, generating unexpected outcomes also in the sphere of international relations.[67] As many of the modernizing elites were heavily influenced by positivism,[68] considering the features and transformations of this outlook[69] could play a much needed role in offering more illuminating studies on the post-Ottoman Empire restructurations in this region.

A further element, which one can also approach in a different and more comprehensive manner, with the help of Global Intellectual History, is the impact and influence of transmitting agents. As already pointed out above in discussing the approach of Acharya and Buzan, IR could become more global by engaging intensively with the role of scholars and thinkers from across the globe. It is at this crossroads that the greatest contributions can originate from more ties to Global Intellectual History. The position of agents with their transnational connections was shown earlier to be one of the distinct features of this novel historiographical turn. At the same time, such a focus should not merely be about connecting the non-West to the West, for it also promises new insights into intra-Western interactions that have been often ignored. With the role of German émigré scholars for the development of IR only lately emerging as a topic of research,[70] it becomes clear that much more needs to be done in order to expand our knowledge about various channels of scholarly interaction, be it direct influence, issues of (mis)translation, or conceptual journeys that at times create more enriched meanings.[71] Most importantly, paying such attention to scholarly undertakings within IR also enables us to be more careful when dealing with the realm of ideas.[72] Otherwise, there awaits often the looming threat of seeing ideas as “timeless entities” leading to their “reification or hypostasisation”.[73]

In the realm of ideas, Global Intellectual History warns us about the dangers of a “modernist bias,” meaning that we should not just focus on the modern era when we look for the global.[74] However, in line with the relevance of the late modern period for IR,[75] I want to point to a 20th century case, a detailed study of which could present us with a better understanding of global politics. Decolonialization, leading to a large number of newly independent states is usually taken into consideration in the context of the concomitant West-East confrontation, with less attention being paid to North-South cross-cutting ties. In this regard, the distinct Yugoslav position under Tito’s co-initiated project of the Non-Aligned Movement[76] could emerge as a useful topic of analysis when it comes to the voyage of ideas and the people who carry, receive, modify and transfer them further. Such a shift of emphasis would be in line with expectations of Global IR in the sense of a broader global outlook, especially when it comes to Yugoslavia’s relations with the Global South, thanks to its leading role in this movement. In addition, such a focus could show that a non-Western, non-Southern state could have ties to countries of the Global South in a way that was not merely shaping both actors’ ideational worlds (social imaginaries)[77] but also changing ideas and mental approaches that had their earlier impact in other contexts of relationships (such as race).[78] Under circumstances when Yugoslavia itself followed a distinct type of socialism, in its own West-East interaction,[79] it is clear that a closer engagement with ideas and their differing meaning would generate a much-needed history on Yugoslavia’s role at the intersection of the ideological and geographical dimensions.[80] This would be a further example of a globally structured intellectual history to IR; one that would also overcome the latter’s Western-centric nature where even Europe’s non-Western regions remain below the radar.

5. Conclusion

The preceding sections established a connection between Global IR and Global Intellectual History, with the addition of some vignettes above that served to elaborate a number of additional aspects of relevance for this interdisciplinary move. This closing section first emphasizes how to create an even broader interdisciplinary framework when it comes to study and understand “the global” in a more comprehensive manner, pointing to a possible triangulation between Global IR, Global Intellectual History, and Global Historical Sociology. Finally, I conclude by putting forward a number of suggestions on how to make the most of Global IR in terms of its prospects in turning IR into a leading player in the broader focus on “the global.” Particularly, this pertains to doing it in a manner that can indeed overcome the discipline’s Western-centric engagements with its subject matters and in the context of its theorizing efforts.

After having shown the usefulness of paying more attention to Global History, and more specifically to Global Intellectual History, for realizing the aims of Global IR, it is also important to acknowledge that one should not stop at this. On the contrary, there is an open space for research with its not much taken paths that includes also other branches of social sciences. In this regard, combining Global IR and Global Intellectual History could serve as just one of many novel approaches to develop. A special role could pertain to the domain of (International) Historical Sociology,[81] or its recent expansion in the shape of Global Historical Sociology.[82] As Osterhammel has also pointed out, with History taking a global turn, it is now easier to relate it,[83] and Intellectual History specifically,[84] more easily to Historical Sociology. This demonstrates to us as scholars of IR the advantages of broadening our interest in neighboring humanities and social sciences in ways that would enable Global IR to connect to similarly formed research interests, gaining in the process new insights and a chance to contribute to this broader focus on “the global.” It is even possible therefore to imagine a triangulated effort connecting the political, the sociological, and the historical.[85]

In light of these interdisciplinary connections, a turn towards a/the Global IR also offers the discipline a means of playing a vanguard role in the broader fields of humanities and social sciences. This can be done thanks to its relatively early-comer status in the “global turn.” As both Global History and (Global) Historical Sociology are rather unsecure within their own fields,[86] IR’s leading role in the study of the “global” in a truly global manner could also make it a prominent player in this turn. Such a move would also contribute to overcome growing fears on the discipline’s unsuccessful competition with other social sciences.[87]

I want to conclude with some further suggestions that refer to our tasks and options ahead. First, a closer focus on Global Intellectual History necessitates a more intensive employment of archival research, or getting familiar with the relevant secondary literature. Much of this can also require comprehensive linguistic skills in order to access documents directly. Second, IR scholars should also be prepared to go beyond their usual textual horizons, following recent calls for dealing with non-textual material in gaining access to the knowledge and ideational frameworks of various cultures.[88] Such a readiness could pave the way for evaluating different societies within the confines of their, at times distinct, practices of producing and sharing knowledge.

Third, intra-IR theoretical or paradigmatic differences will still play a major role in determining our ways of engagement. Notwithstanding Acharya and Buzan’s preference for non-discrimination among theories (but merely a wish for their broadening by interaction with non-Western sources),[89] especially realism could have difficulties in realizing the promises of Global IR. However, even there it seems important to underline how a close attention for ideas could play a significant role in furthering this theory itself. By understanding how an idea like Realpolitik has undergone a dramatic conceptual transformation before reaching the realist shores, it becomes clear that there is much to be gained with a focus on Global Intellectual History.[90] Fourth, engaging with Global Intellectual History means not only looking at the historical past, but also focusing on the intermediaries, popularizers, transmitters, that is, agents who have developed, changed, (mis)translated, and vulgarized[91] existing ideas. In this regard, Global IR’s much emphasized quest for a more intensive engagement with classical thought, as well as different past and present thinkers and political leaders,[92] needs to be strengthened by turning our attention to recent methodological, and epistemological debates that emerged with the impact of Global (Intellectual) History.

Last but not least, Global IR carries in itself, perhaps unconsciously, the seeds of a gradual return to its earlier interwar years, to a time when it used to be more interdisciplinary in its approaches.[93] Here lies thus a novel promise that should lead us to re-think our discipline’s role in a period of globality, with all its opportunities and dangers. Engaging with neighboring disciplines, be it History or Sociology, with their specialized subfields that offer possibilities for intensive cooperation, is the step ahead.

Acharya, Amitav. “Advancing Global IR: Challenges, Contentions, and Contributions.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 4–15.

–––. “Dialogue and Discovery: In Search of International Relations Theories beyond the West.” Millennium 39, no. 3 (2011): 619–37.

–––. “Global International Relations (IR) and Regional Worlds: A New Agenda for International Studies.” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 4 (2014): 647–59.

Acharya, Amitav, and Barry Buzan. The Making of Global International Relations: Origins and Evolution of IR at Its Centenary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Acharya, Amitav, and Barry Buzan, eds. Non-Western International Relations Theory: Perspectives from Asia. London: Routledge, 2009.

Acharya, Amitav, and Barry Buzan. “Why Is There No Non-Western International Relations Theory? An Introduction.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 7, no. 3 (2007): 287–312.

Armitage, David. Foundations of Modern International Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

–––. “The International Turn in Intellectual History.” In Rethinking Modern European Intellectual History, edited by Darrin M. McMahon, and Samuel Moyn, 232–52. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

Aydın, Cemil. “Approaches to Global Intellectual History.” In Moyn and Sartori, Global Intellectual History, 159–86.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Julie Mathews. “Periphery Theorising for a Truly Internationalised Discipline: Spinning IR Theory out of Anatolia.” Review of International Studies 34, no. 4 (2008): 693–712.

Baker, Catherine. Race and the Yugoslav Region: Postsocialist, Post-conflict, Postcolonial? Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018.

Bakhle, Janaki. “Putting Global Intellectual History in Its Place.” In Moyn and Sartori, Global Intellectual History, 228–53.

Belich, James, John Darwin, and Chris Wickham. “Introduction.” In Belich, Darwin, Frenz, and Wickham, The Prospect of Global History, 3–22.

Belich, James, John Darwin, Margret Frenz, and Chris Wickham, eds. The Prospect of Global History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Bell, Duncan. “Making and Taking Worlds.” In Moyn and Sartori, Global Intellectual History, 254–79.

Bew, John. Realpolitik: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Bilgin, Pinar. “Thinking Past ‘Western’ IR?” Third World Quarterly 29, no. 1 (2008): 5–23.

Blaney, David L., and Arlene B. Tickner. “Worlding, Ontological Politics and the Possibility of a Decolonial IR.” Millennium 45, no. 3 (2017): 293–311.

Brown, Chris, Caroline Kennedy-Pipe, Andrew Linklater, and Ken Booth. “Roundtable: `The Future of the Discipline’.” International Relations 21, no. 3 (2007): 346–46.

Byrne, Jeffrey James. “Beyond Continents, Colours, and the Cold War: Yugoslavia, Algeria, and the Struggle for Non-Alignment.” The International History Review 37, no. 5 (2015): 912–32.

Budde, Gunilla-Friederike, Sebastian Conrad, and Oliver Janz, eds. Transnationale Geschichte Themen, Tendenzen und Theorien. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2010.

Buzan, Barry, and George Lawson. The Global Transformation: History, Modernity and the Making of International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Chatterjee, Partha. “A Brief History of Subaltern Studies.” In Budde, Conrad, and Janz, Transnationale Geschichte, 94-104.

Conrad, Sebastian. What Is Global History?. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Conrad, Sebastian, and Andreas Eckert, eds. Globalgeschichte: Theorien, Ansätze, Themen. Frankfurt; New York: Campus, 2007.

Cooper, Frederick. “How Global Do We Want Our Intellectual History to Be?” In Moyn and Sartori, Global Intellectual History, 283–294.

Darwin, John. “Afterword.” In Belich, Darwin, Frenz, and Wickham, The Prospect of Global History, 178–84.

Go, Julian, and George Lawson, eds. Global Historical Sociology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Goering, D. Timothy, ed. Ideengeschichte Heute: Traditionen und Perspektiven. Bielefeld: Transcript, 2017.

Gruffydd Jones, Branwen, ed. Decolonizing International Relations. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2006.

Hanioğlu, M. Şükrü. Atatürk: An Intellectual Biography. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Helleiner, Eric, and Antulio Rosales. “Toward Global IPE: The Overlooked Significance of the Haya-Mariátegui Debate.” International Studies Review 19, no. 4 (2017): 667–91.

Herbjørnsrud, Dag. “Beyond Decolonizing: Global Intellectual History and Reconstruction of a Comparative Method.” Global Intellectual History (2019). doi: 10.1080/23801883.2019.1616310.

Hill, Christopher L. “Conceptual Universalization in the Transnational Nineteenth Century.” In Moyn and Sartori, Global Intellectual History, 134–58.

Hobden, Stephen, and John M. Hobson, eds. Historical Sociology of International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Hobson, John M. The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics: Western International Theory, 1760-2010. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Hoffmann, Stanley. “An American Social Science: International Relations.” Daedalus 106, no. 3 (1977): 41–60.

Iriye, Akira. Global and Transnational History: The Past, Present, and Future. Palgrave Pivot, 2013.

Jackson, Patrick Thaddeus. The Conduct of Inquiry in International Relations: Philosophy of Science and Its Implications for the Study of World Politics. New York: Routledge, 2011.

Juergensmeyer, Mark, Manfred B. Steger, Saskia Sassen, and Victor Faessel, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Global Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Kapila, Shruti. “Global Intellectual History and the Indian Political.” In Rethinking Modern European Intellectual History, edited by Darrin M McMahon, and Samuel Moyn, 253–74. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

Kaviraj, Sudipta. “Global Intellectual History: Meanings and Methods.” In Moyn and Sartori, Global Intellectual History, 295–319.

Krell, Gert and Peter Schlotter. Weltbilder und Weltordnung – Einführung in die Theorie der Internationalen Beziehungen. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2018.

Levine, Emily J. “Homo Academicus Localis: The Circulation of Ideas in an International Context." in Ideengeschichte Heute: Traditionen und Perspektiven, edited by D.Timothy Goering. Bielefeld : Transcript, 2017.

Ling, Lily HM. “Decolonizing the International: Towards Multiple Emotional Worlds.” International Theory 6, no. 3 (2014): 579–83.

Long, David. “Who Killed the International Studies Conference?” Review of International Studies 32, no. 4 (2006): 603–22.

Massad, Joseph. “Against Self-Determination.” Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development 9, no. 2 (2018): 161–91.

Matin, Kamran. “Redeeming the Universal: Postcolonialism and the Inner Life of Eurocentrism.” European Journal of International Relations 19, no. 2 (2013): 353–77.

McMahon, Darrin M., and Samuel Moyn, eds. Rethinking Modern European Intellectual History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

Mignolo, Walter. “The Geopolitics of Knowledge and the Colonial Difference.” The South Atlantic Quarterly 101, no. 1 (2002): 57–96.

Moyn, Samuel. “Imaginary Intellectual History.” In Rethinking Modern European Intellectual History, edited by Darrin M. McMahon, and Samuel Moyn, 112-130. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

–––. “On the Nonglobalization of Ideas.” In Moyn and Sartori, Global Intellectual History, 187–204.

Moyn, Samuel, and Andrew Sartori. “Approaches to Global Intellectual History.” In Moyn and Sartori, Global Intellectual History, 3–32.

Moyn, Samuel, and Andrew Sartori, eds. Global Intellectual History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

Osterhammel, Jürgen. “Global History and Historical Sociology.” In Belich, Darwin, Frenz, and Wickham, The Prospect of Global History, 23–43.

Özervarlı, M. Sait. “Positivism in the Late Ottoman Empire: The ‘Young Turks’ as Mediators and Multipliers.” In The Worlds of Positivism, edited by Johannes Feichtinger, Franz L. Fillafer, and Jan Surman, 81–108. Cham: Springer International, 2018.

Phillips, Andrew. “Global IR Meets Global History: Sovereignty, Modernity, and the International System’s Expansion in the Indian Ocean Region.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1( 2016): 62–77.

Quijano, Anibal. “Coloniality of Power and Eurocentrism in Latin America.” International Sociology 15, no. 2 (2000): 215–32.

Riemens, Michael. “International Academic Cooperation on International Relations in the Interwar Period: The International Studies Conference.” Review of International Studies 37, no. 2 (2011): 911–28.

Robertson, James M. “Navigating the Postwar Liberal Order: Autonomy, Creativity and Modernism in Socialist Yugoslavia, 1949–1953.” Modern Intellectual History (2018). doi: 10.1017/S1479244318000379.

Rollo, Toby. 2018. “Back to the Rough Ground: Textual, Oral and Enactive Meaning in Comparative Political Theory.” European Journal of Political Theory, doi: 10.1177/14744885118795284.

Rösch, Felix. “Policing Intellectual Boundaries? Émigré Scholars, the Council on Foreign Relations Study Group on International Theory, and American International Relations in the 1950s.” The International History Review (2019). doi: 10.1080/07075332.2019.1598464.

Rösch, Felix, and Atsuko Watanabe. “Approaching the Unsynthesizable in International Politics: Giving Substance to Security Discourses through Basso Ostinato ?” European Journal of International Relations 23, no. 3 (2017): 609–29.

Rosenboim, Or. Emergence of Globalism: Visions of World Order in Britain and the United States 1939-1950. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017.

–––. “Threads and Boundaries: Rethinking the Intellectual History of International Relations.” In Historiographical Investigations in International Relations, edited by Brian C. Schmidt and Nicolas Guilhot, 97-125. The Palgrave Macmillan History of International Thought. Cham: Springer International, 2019.

Rotschild, Emma. “Arc of Ideas. International History and Intellectual History.” In Budde, Conrad, and Janz, Transnationale geschichte, 217–26.

Sartori, Andrew. “Global Intellectual History and the History of Political Economy.” In Moyn and Sartori, Global Intellectual History, 110–33.

Schmidt, Brian C. “Internalism Versus Externalism in the Disciplinary History of International Relations.” In Historiographical Investigations in International Relations, edited by Brian C. Schmidt and Nicolas Guilhot, 127–48. The Palgrave Macmillan History of International Thought. Cham: Springer International, 2019.

–––. The Political Discourse of Anarchy: A Disciplinary History of International Relations. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1998.

Seth, Sanjay. Postcolonial Theory and International Relations: A Critical Introduction. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Söllner, Alfons. Deutsche Politikwissenschaftler in der Emigration: Studien zu ihrer Akkulturation und Wirkungsgeschichte. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1996.

–––. Political Scholar: Zur Intellektuellengeschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts. Hamburg: CEP Europäische Verlagsanstalt, 2018.

Subotic, Jelena, and Srdjan Vucetic. “Performing Solidarity: Whiteness and Status-Seeking in the Non-Aligned World.” Journal of International Relations and Development (2017). doi: 10.1057/s41268-017-0112-2.

Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. “Global Intellectual History beyond Hegel and Marx.” History and Theory 54, no. 1 (2015): 126–37.

Tickner, Arlene. “Seeing IR Differently: Notes from the Third World.” Millennium 32, no. 2 (2003): 295–324.

Tickner, Arlene B. “Hearing Latin American Voices in International Relations Studies.” International Studies Perspectives 4, no. 4 (2003): 325–50.

Tickner, Arlene B., and Ole Wæver, eds. International Relations Scholarship around the World. New York: Routledge, 2009.

Whatmore, Richard. What Is Intellectual History? Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2016.

Wight, Colin. Agents, Structures and International Relations Politics as Ontology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Zehfuss, Maja. “Constructivism and Identity: A Dangerous Liaison.” European Journal of International Relations 7, no. 3(2001): 315–48.

Zimmerman, Andrew. “Conclusion: Global Historical Sociology and Transnational History – History and Theory Against Eurocentrism.” In Global Historical Sociology, edited by Julian Go and George Lawson, 221–40. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Životić, Aleksandar, and Jovan Čavoški. “On the Road to Belgrade: Yugoslavia, Third World Neutrals, and the Evolution of Global Non-Alignment, 1954–1961.” Journal of Cold War Studies 18, no. 4(2016): 79–97.