Melisa Deciancio

FLACSO Argentina/CONICET

Cintia Quiliconi

FLACSO Ecuador

The field of IPE has traditionally being conceptualized as an Anglo Saxon construct, in this paper we argue that it is critically important to reflect on the way IPE has developed outside the mainstream, in the periphery, focusing on the case studies of Africa – in particular South Africa; Asia – in particular China; and South America, in order to start a conversation that engages with the contributions of peripheral IPE. By bringing to light the way IPE has been approached in these regions of the world we identify problems, ideas, and concerns different from those in the North and which also call attention to the necessity of a conscious reading of these works and to opening a dialogue and comparison among them. The paper explores the contributions made by IPE in Africa, Asia and South America in order to discuss the possibility of widening IPE’s ‘global conversation’ including peripheral approaches.

1. Introduction

In 2008 Benjamin Cohen in his book “International Political Economy (IPE): An Intellectual History” proposed a global conversation within the IPE field. However, the center of that ‘global’ dialogue was American and British IPEs, focused on English speaking authors and approaches as he mainly explored the composition of IPE in the United States and Europe. Along the same lines, in the last decades several authors have started to reflect about academic fields like International Relations (IR) and IPE, in close connection with the growing development that those fields have had around the globe. This development has spurred a number of criticisms about Western approaches in both IR[1] and more incipiently in IPE,[2] that strive to develop new lines of research that bring the periphery[3] to the center of the scene, constructing alternative contributions to those imposed and/or disseminated from the centers of world power. Thus, lately, some relevant studies have emerged on the role that national and regional schools occupy within social sciences and the work of numerous scholars has aimed at making them more ‘global’[4]. As Beigel points out, “the main differences between mainstream academies and peripheral circuits are not precisely in the lack of indigenous thinking, but in the historical structure of academic autonomy”,[5] in other words, the scarce recognition and awareness of peripheral knowledge in mainstream debates. A global approach to IPE does not mean just setting the lens at the global level; on the contrary it means as Narlikar brings up that “we no longer allow the marginalization of the ‘rest’...from the mainstream debate. It means not being ‘critical’ for the sake of it, but engaging with content from the South/ the regions – be it theoretical or empirical- on its own terms. The two keywords that define this content are inclusiveness and pluralism”.[6]

Political economy is about the sources of political power and its uses for economic ends; it is about the co-constitutive relations among the market, the state and the society. As power distribution varies around the globe, so does development and its approach to it. As Benjamin Cohen puts it, “the field of International Political Economy (IPE) teaches us how to think about the connections between economics and politics beyond the confines of a single state”.[7] However, not all states look alike. As ideas and knowledge travel, so do disciplines. The way IPE developed in the center set the main bases of its study in other regions of the world, focusing on the way markets and power operate worldwide. However, when approaching the way IPE developed in the periphery, particularities emerged, and a whole set of conceptualizations and questions that differ in great manner from those in the center have appeared. Markets, states and power are main concerns in the capitalist world we live in but the way we think about that interaction changes if we are on one side of the globe or the other(s). Enquiries, ideas, methodologies and analysis in the periphery are proof of that. Thinking capitalism from the core - namely Europe and the US - has a completely different approach than thinking it from other areas of the world; thinking capitalism from the perspective of developed countries is completely different from thinking it from that of the developing world or as an emerging economy. Problems and approaches vary depending on how you are inserted in the international economy structure, if you are a rule maker or a rule taker, if you are a producer of manufactures or a commodity exporter, if you are a creditor or a debtor.

Within this framework, we highlight the global character of IPE not in its scope but mainly in the recognition of its theoretical and empirical roots. We also ask, what are the main drivers that IPE has experienced in Africa, China and South America? We compare these regions in order to understand how peripheral IPE has developed and also to highlight its main and barely recognized contributions within the mainstream IPE. Since IPE as a field started to develop in the 1970s in the core, it is assumed that its main ideas then traveled to the periphery in the following decades; but in fact, many of the main IPE questions were being explored in Latin America and other regions as development debates or dependency debates much before this decade. In this sense, it is important to consider whether IPE’s conversation can be international given that ‘globalizing’ fields of research can also constitute a trap to achieve those knowledge international standards. As globalization itself became a way of homogenization and westernization of the rest of the world, making disciplines more global (despite such efforts’ good intentions) could also be, on the one hand, the way the mainstream comprises concepts and ideas from other regions of the world but does nothing with them and, on the other hand, the ways in which the periphery embraces mainstream and critical IPE concepts to adapt its own IPE production to mainstream standards imposed from the North. In this sense, we can think of IPE as being global in its subject study, but we can question its globalizing scope in Western academic terms showing the risk that internationalization creates for the way different parts of the world approach IPE in its own terms. Making it global can also mean making peripheral problems more diffuse, blurry and imperceptible, which can imply that the only ones capable of thinking about and developing solutions to those problems are the same ones that cause them. In this sense, inclusiveness can only be assured if we are ready to take into account excluded voices and pluralism can only be achieved if we are willing to recognize alternative ideas, theories and even practices.[8]

In this paper we address the way IPE developed outside the mainstream, in the periphery, focusing on the case studies of Africa – particularly South Africa; Asia - particularly China; and South America in order to call for a deeper and stronger conversation among peripheral countries and with the intention of enhancing a debate about their own production and debates leaving aside mainstream standards. We assume the core to be mainstream Western or Anglo-Saxon IPE (specially developed in the US and the UK), while the periphery will be constituted by non-western and Global South approaches. Bringing to light the way that IPE has been addressed in these regions of the world will allow us to identify problems, ideas, and concerns different from those in the North, and also call attention to the necessity of conscious reading of these works in order to develop suitable solutions to the market-power dynamics affecting ‘the rest of the world’. It seeks to explore the contributions made by locally grounded IPE in order to open up discussion about the possibility of widening IPE’s ‘global conversation’ to include peripheral approaches and embracing its contributions in an inclusive way.

2. From Decolonization to Foreign Aid: The Basis of the IPE Field in Africa

African IPE has been almost entirely unexamined, and disciplinary reflections on it are mostly nonexistent. Although IPE as a field of research--as considered in Western universities--is quite new, in African research institutions studies on development and political economy relations date back to the 1960s when IR was first being institutionalized as a discipline.[9] In fact, development studies pioneered the studies of IR along with debates on decolonization. As can be seen in the Latin American case, in Development Studies a political economy dimension was present from the beginning but not considered within Western/mainstream IPE standards as part of the field. Structural and institutional factors were assigned a key role in the development process. As Ohiorhenuan and Keeler pointed out, in the initial phase of the field, the state was also assigned a large role in promoting development almost as an historical imperative.[10] Dependency theorists in the 1960s and 1970s explicitly introduced a political economy dimension to analyze the asymmetric relationships among the industrial primary producing countries.[11] As such, Development Studies considered within the wider definition of IPE have a long tradition in Africa. Questions of poverty, development, and underdevelopment have always been key in the debates concerning African IPE.[12]

In Africa, IR works that “travelled” were developed more from outside the continent[13] than from within, often defined and oriented by the dominant international and geopolitical agendas of the day.[14] In Western IR, although they haven’t been completely absent, African states have not constituted a key core theoretical concern of either IR or IPE. This lack of attention by the IR field is still surprising. Where there have been attempts at bringing Africa into the fold, it has been done from the perspective of ‘what can Western IR do to incorporate Africa’, rather than ‘what can we learn from Africa,’[15] a trend that is similar in all the regions addressed in this paper. In fact, the literature on colonialism and imperialism in Africa existed parallel to the development of mainstream western IR but was left aside by it.

Within IPE, the main change was made during the postwar and postcolonial era, when world system theory and ‘development studies’ began considering Africa as part of the debate. These investigations acknowledged that the economic governance structures of the former colonial metropole directed the postcolonial economies.[16] However, we argue that as development studies have always been separated from IPE, and African countries were only included in the analysis as ‘case studies’ but not as agents of knowledge production, the local contribution of African IPE has been under-recognized in Western IPE.

After political independence, the preoccupation was the search for economic and social independence. During the 1970s, debates within African IPE were mainly focused on inequalities, but the orthodox paradigms were more preoccupied with notions of modernization, political capacity, and political responsiveness, as well as with concepts of development, adaptation, integration, and unity. Social scientists borrowed from the Latin American ‘dependentist’ school in their aim to develop their own approach to local problems. Scholars such as Samir Amin and Walter Rodney focused their research on the causes of Africa’s underdevelopment.[17] This line opened the path to a neo-Marxist approach led by Amin and Segun Osoba,[18] who criticized other scholars for being super-structural and state-centric, and for assuming the state in the developing world as an autonomous actor rather than an instrument of foreign states and global capitalism. Along with Immanuel Wallerstein’s world-systems approach most African representatives of this school highlighted the external constraints imposed on African societies, and focused their attention on emerging class conflicts.[19] However, as Ofuho points out, although providing new insights into the role of capitalism in constraining African development, this approach was not in vogue for long: “Dependency theory imposed uniformity in the study of contemporary Africa, thus treating the continent as if it were a homogenous entity. In concentrating upon external sources of dependency, it also failed to consider the intricacies of the domestic political upheavals that engaged in the continent during the 1970s and the 1980s”.[20] Along the same lines, Algerian jurist, Mohammed Bedjaoui, provided the most elaborate legal-theoretical articulation of how to accomplish the economic objectives of the New International Economic Order. Bedjaoui criticized the existing formal structure of international law, as organized to systematically favor former imperial powers, reflecting and enabling the structural inequality of the global economy.[21]

In the 1990s, the centrality of neoliberal economic arguments began to be challenged from African IPE with a pragmatic perspective. After more than two decades of liberal market reform throughout much of Africa, belief in the positive power and effects of markets alleviating the African economic condition began to be opened to empirical contestation in the region. There was no firm consensus on the effects of liberal market reforms in Africa, but a powerful and growing African perspective began to argue that these reforms not only failed to improve the African condition, but made it worse.[22] The importance of this perspective as a criticism of the liberal paradigm cannot be overstated, because if true, the liberal assumption in international relations of open markets offering opportunities for mutual gain was out of necessity opened up to question.[23]

Despite the contributions outlined above, African IPE as a constituted and institutionalized field is quite new by Anglo-Saxon academic standards. Scholars working on the field have been mainly based in universities’ departments and think tanks that emerged in order to deal with African IR, particularly Africa’s place in the global economy and African security issues. In South Africa, for example, The South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), the Institute for Global Dialogue (IGD), the Centre for Conflict Resolution (CCR), the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS) and to a lesser extent the Institute for Strategic Studies (ISSUP) and the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) have led the debates on IR and, to a lesser extent, IPE. The Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) based in Dakar, Senegal has been mainly focused on security and education issues, but has included some IPE works among its publications.[24]

Regarding the dissemination of African IPE works, we found that IPE journals are scarce in Africa. The most specialized journal both in terms of relevance and theme, is the Review of African Political Economy (ROAPE), which has been published by Taylor & Francis since 1974. Although not specifically international, this journal brings together the main debates by African and non-African scholars about Africa’s IPE. The first article of the first issue was Samir Amin’s seminal work “Accumulation and development: a theoretical model”.[25] The most relevant journals publishing IR issues, both based in South Africa, are Politikon, the journal of the South African Association of Political Science (SAAPS), and the South African Journal of International Affairs (SAJIA) published by SAIIA.

In recent decades African IPE has been addressing the specificity of African economies, marked by the participation of foreign actors in their economic structure, also discussing foreign aid and its consequences, issues which have marked a strong part of African IPE debates. In South Africa, although not much IPE doctoral work has been produced, such specialization is to be found in university teaching at Cape Town, Pretoria, Johannesburg, Rhodes and Stellenbosch. More recent African IPE has focused, firstly, on the political and economic implications of foreign aid, especially addressing the administration of these funds and the political and economic implications they have on the continent.[26] The actors involved in the administration of the funds also differ from other regions of the world. Compared to Latina America or Asia, a large percentage of the capital entering and exiting African economies either is mediated by public-sector organizations and/or NGOs, or is not captured in official records.

3. Marxism, State-led Development and Hegemony: IPE with Chinese Characteristics

Though the IPE field started to develop in the 1970s and took off in the mid 1980s it was not until the 1990s that it began to emerge in China. Song[27] attributed the neglected of IPE in China to the following reasons: mutual isolation of universities from research institutions in a situation in which scholars studying international politics knew little about international economy and vice versa, and an approach based on policy-oriented research and applied studies, given that academic research in China has a close link with national policies. In this sense, the Marxian theoretical approach was central until the 1990s when western IPE as a set of concepts caught on quickly among Chinese scholars.

There was an important level of academic insularity in China that was understandable, given the relatively limited involvement that the country experienced in international markets in the 1970s and 1980s.[28] In this sense, the dominant approaches to studying China’s international relations and IPE overemphasized the national level of analysis and were built on statist and realist notions of international relations that are also reflected in the way in which IPE has emerged as a field of enquiry within China itself. Most academic explanations of China’s reforms, and even its foreign policy, have been based on domestic politics and have paid less attention to the international dimension. Song argues that “the divides which separate disciplines and institutions are still very deep in China,” and that this is a consequence of “the social setting in which the study of IR and IPE in China takes place – namely, the dominance of policy related research, the residual ideology, and the fact that the state remains a very powerful force in current China.[29] These factors combined reinforce the separation of disciplines and have obstructed the emergence of an IPE field, which considers the importance of non-state actors and economics in general.”[30] Given that IPE is by definition multidisciplinary and international in its underpinnings, the separation of disciplines and the focus on domestic rather that international variables have worked as impeding forces to the development of the field.

Nonetheless, some ideas have gained traction and influence, but with some important differences from the basic assumptions of IPE in the West. Particularly, the roots in Marxian thinking as the official doctrine since 1949 and China’s socialist economy were simply too powerful, preventing changes in global prices or international economic forces from affecting domestic prices, domestic supply and demand. According to Chin, Pearson and Yong[31] the enduring influence of Marxian political economy was related to the fact that the approach dominated the analysis of all major social sciences and of think tanks such as the Institute for Marxism at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), which have historically received privileged funding from the state.

As Marxist ideology dominated Chinese society until the 1980s, academic studies in IPE strictly followed the Communist Party line. Triggered by economic reforms after 1980, the previous hard stand taken by the government was softened in order to justify the need of inviting foreign capital, technology, and professionals to China. As they were mainly from the West, the inflow of information including international institutions, whether regionally or politically orientated (NATO or the European Union) or economy-related (the IMF and World Bank among others), this interaction taught the Chinese how to deal with or make use of their functions in the world.

The global rise of China and particularly China’s ‘open policy,’ and its deeper engagement with the global economy allowed a more suitable environment for Western IPE to become known by Chinese scholars. In the 1990s a new momentum triggered by the promotion to a higher level of the open-door policy supported by Deng Xioping to open China up to foreign investments vis-á-vis high-speed economic growth, allowed for the introduction of mainstream IPE. Concepts such as globalization and interdependence began to be widely discussed in China and, given the more open times, IPE escaped the typical fate of Western international relations theories that usually were suspected, selectively introduced, criticized and modified.[32]

In general, the development of IPE in China is divided into three phases. The first phase, which lasted until the 1990s, marked a period in which a Marxist view and structuralist ideas dominated the field. The second phase, which started in the 1990s, is when the field became institutionalized as the Ministry of Education recognized IPE as an official subject to study in international politics and diplomacy.[33] While the very first texts on IPE lean on classical Marxist views,[34] later ones began to incorporate Western ideas[35] as the IPE field blossomed in many universities. Finally, a third period began in the 2000s, as Western IPE became fully incorporated in Chinese academia and began to share similarities with the Global North debates.

Looking within China there is a diversity of IPE views, but three concepts have been key in Chinese IPE: development; hegemony; and globalization. These concepts have been related with the Chinese need to respond to changes in official policy and the norms of the governing Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In this sense, we agree with Chin, Pearson and Yong[36] that Chinese IPE is powerfully induced by political power and the role of the CCP defining the parameters of the policy and academic debates, which are closely intertwined and which set ideas as the dominant and correct approach.

Finally, in terms of publishing venues, there are various journals that publish IPE articles in China, among the most relevant appear to be Comparative Economic and Social Systems, International Economic Review, International Politics Quarterly, Studies on Marxism, and World Economics and Politics, most of which are published by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The Journal China Political Economy is on online journal that was launched in 2018 and is managed by an editor on Nanjing University. However, taking a look at the articles that are published we see a trend in which IPE topics are not the majority of the issues addressed in these publications. They also tend to publish mainly Chinese authors, showing that, despite embracing Western IPE, true internationalization of their journals is still rare. As Chin, Pearson and Yong[37] point out, there are various institutions that currently offer programs that study IPE, among them Renmin University China (People`s University), which was the first to incorporate the study of IPE in the 1990s, as well as also other institutions such as Fudan University and Peking University that developed specialized programs in the late 1990s or start of the 2000s. In a similar vein, recently, in 2011, the CASS created the Institute of World Economy and Politics. The spread of programs, journals and academics shows that the IPE field is gradually consolidating in China and is embracing new approaches related to the West.

4. Dependency, Development and Regionalism in South American IPE

Diana Tussie points out that, in South America, IPE had two strong pushes: the first ignition marked by the impulse of Dependency theory; and another more recent one, in the 1990s, with the creation of Mercosur, the re-launching of the Andean Community and the blossoming of the regional integration debate.[38] This second stimulus gave a less deterministic tone to academic research that at the same time initiated a dialogue and a more intimate interaction with public policy. Both show the great amount of changes that have marked the development of IPE, granting them their own characteristics and altering their course. This approach to IPE and theoretical developments transcended national borders to become a phenomenon of regional scale. That is why it wouldn’t be accurate to address these contributions as exclusively of one country, although much of the debate was in fact driven by Raúl Prebisch, an Argentine intellectual. Since its beginnings, Latin American IPE has been a phenomenon that developed at the regional level and that stimulated studies on this and other branches of the discipline in many Latin American countries. While various scholars in Latin America have emerged from development, others have close ties with Economic History and Sociology, enabling spaces for situated knowledge and even more important, methodologically, for considering wider conceptions of agency.[39] Within this framework, the study of regions and regionalism acquired special relevance. This does not imply that this has been the only contribution of Latin American IPE but it has been the one that emerged as one of the most relevant research issues within the IR discipline, along with the more preponderant studies of foreign policy and international security.[40] Latin American versions of Developmental Sociology and Developmental Economics, based on structuralism, critical sociology and dependency theory, were expressions of the ability of social scientists in the region to confront dominant ideas in the international debate questioning conventional wisdom and transforming it to reinvent it.[41] This origin opened up the door to multidisciplinary works, allowing a fertile ground for IPE to grow.

In Latin American IR, field attention has mainly been centered on such issues as the Cold War, Defense, and Security, and national and regional Foreign Policies, with indifference and even denial given to the gravity of economic forces and market operators. It is in part for this reason that IPE constantly calls into question analyses that presume an excessive autonomy of economics over politics. For Guzzini, for example, IPE emerged as a reaction, partly in favor and partly against, the much more systemic--but restricted--neorealist IR theory proposed by Kenneth Waltz.[42]

By the end of the 1970s, political economy gained strength from scholars’ discomfort with the distance between abstract models of political and economic behavior and what was really happening in Latin American economies and politics. At the same time, economic crises were becoming increasingly politicized while concerns within political systems on economic factors started to increase.[43]

Economics and Economic Sociology were key fields in Latin America that contributed to the development of an approach to IR where new actors and processes were included in a field that, as noted earlier, was traditionally centered on the State as the main actor and producer of international relations. The inclusion of economic variables and forces into the dynamics of foreign relations was mainly motivated, in its beginnings, by the regional integrationist proposals as the peripheral place of the region in international economic relations was assumed. As a result, from the first works of Argentine engineer Alejandro Bunge and his proposal to create a Southern Customs Union, to the integrationist project of the 1960s, led by Raúl Prebisch and Latin American developmentalists, studies on regional integration have marked and promoted IPE in Latin America. As a result, by the 1960s, center-periphery tensions established a new understanding of international politics. At the same time, the IR field started to be recognized as an autonomous discipline as it was institutionalized in universities in the context of a growing sense of urgency regarding the political and economic dependence of the region.[44] Thus, three schools can be seen as key in the development of IPE in South America: structuralism; dependency; and autonomy; all three of which have close links to the analysis of practical problems that the region was experiencing.

Until the 1980s, IPE was marked by studies on regional integration and regionalism, constituting also one of the main contributions from Latin America to global IR[45] and with a clear Southern perspective closely related to the emergence and development of regional organizations. In a way, to draw parallels with the European process, while the theory of European regional integration had its roots in the Social Sciences, Latin American regional integration has its roots in Latin American political economy[46] and, more specifically, in a regional vision of IPE.[47]

This Latin American IPE knowledge production was developed in a group of regional institutions, among the most important ones highlighted in the literature being the Economic Commission for Latin American and the Caribbean (ECLAC), created in 1948; the Latin American School of Social Sciences (FLACSO), founded in 1957; the Institute for Integration of Latin America (INTAL), originated in 1965; the Latin American Council for Social Sciences (CLACSO), organized in 1967; and the Latin American and Caribbean Economic System (SELA)[48] and the Argentine Centro de Estudios de Estado y Sociedad (CEDES), both dating from 1975.[49] Over the years, many universities in the region have been addressing IPE topics inspired by the debates produced by these regional institutions.

In the 2000s, new agendas and approaches to South American regionalism emerged, accompanying the creation of new regional organizations such as the Bolivarian Alliance of the People of Our Americas (ALBA), the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), regional groupings that were labeled by the literature as postliberal,[50] posthegemonic,[51] and post-trade.[52] These approaches delineated a new set of conceptualizations to explain the turn in policy. Since UNASUR and CELAC had a rich agenda of functional cooperation, they opened up the studies of sectoral agendas of cooperation in regionalism, ranging from defense, drugs and security,[53] health,[54] and migration[55] to infrastructure, energy and the environment.[56] This new set of regional arrangements and the variety of issues and evolving agendas bringing them together led to the debate on what kind of regionalism and overlapping of institutions the region was experiencing.[57]

Many of the debates on regionalism and regional cooperation were published not only in books but also in South American journals. In terms of specific journals publishing IPE articles in South America, for those that belong to the Scimago- Scopus database, we can only mention the Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, but there is a group of journals in political science and international relations that tend to publish IPE articles even though are not exclusively dedicated to IPE topics. Among them the most relevant ones publishing IPE articles are Colombia Internacional (Colombia), Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional (Brazil), and Estudos Internacionais (Brazil). There has also been an important trend in the region to create new International Relations and Political Science journals that publish IPE articles, among them we can mention Revista de Relaciones Internacionales and Desarrollo Económico (Argentina), Revista Uruguaya de Ciencia Polítia (Uruguay), Contexto Internacional (Colombia), Lua Nova (Brazil), Novos Estudos CEBRAP (Brazil), Revista de Sociología e Política and Carta Internacional (Brazil); Revista Chilena de Relaciones Internacionales (Chile); and Análisis Político and Desafíos (Colombia), as being among the most relevant ones.

5. IPE and the Limits of the Global Conversation: Bringing the Periphery in

Political economy has always been part of IR[58] and as such, IPE (and IR in general) has been considered a discipline designed by and especially outlined by the experiences and problems of the US and European central countries. This reality determined not only who dominated the field but also which tools and debates would constitute its mainstream. In recent years, this deep and ponderous intellectual dominance has led to many reflections from different parts of the world on the task of developing their own approaches or recovering local and regional ones to offer a broader vision of the discipline, alerted by its narrowness and by the denial of the existence of voices, experiences, knowledge, and perspectives from outside the centers. Also exposed have been the limitations of theories and approaches developed by the centers to explain--and specially to modify--the realities of the periphery. Therefore, the reflection has focused on the one-way street in the circulation of knowledge between center and periphery, and, for the focus of this paper, how that circulation has marked the way IPE has developed in other parts of the world.

It is known that IPE has achieved its greatest development in the English-speaking world, both in methodological and theoretical terms. As Benjamin Cohen[59] points out, “globally, the dominant version of IPE (we might even say the hegemonic version) is one that has developed in the United States, where most scholarship tends to stay close to the norms of conventional social science”[60] and where ‘the other’ is only British IPE.[61] As a result, on the one hand, geographically, Anglo-Saxon academia became the reference point for the development of IPE in the world, while on the other hand, the study of ‘the other’ has been mainly focused on the transatlantic dialogue between North American and British IPE. In theoretical terms, the conversation tends to leave behind Marxism, critical IPE studies and many idiosyncratic views that do not encompass a dialogue with Anglo-Saxon mainstream IPE or incorporate their methodological standards.

To make this scenario even more complex, in the periphery, the adoption of theories and ideas from the centers were largely accepted indiscriminately without considering the structural differences among geographies. When compared with the experience of the US and European countries, the study of IPE in the periphery may seem relatively recent, but it is certainly not absent or completely new. While the development of IPE in the center came about due to challenges arising from the dynamics between markets and power, in other regions of the world the field and its main formulations developed in association with the emergence of real challenges from both the international economic scenario and the different strategies of insertion into the global economy developed by those regions. IPE in the periphery has been marked by the struggle for economic development, access to credit and foreign aid, debt payment, regional integration to access a better international insertion, and adding value to its exports. These concerns put the focus on different needs and required different approaches from those of developed countries to understand their realities.

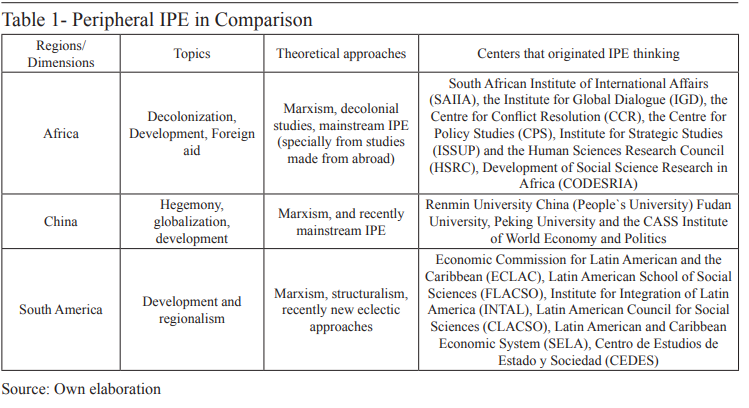

The discussion on the place that periphery has in mainstream debates has been mainly addressed by IR scholars. Several authors have pointed out the narrowness of IR theory that has arisen from the Western world centers does not serve to explain the reality of those located in the periphery because they left aside voices, experiences, knowledge and perspectives from outside of the centers.[62] For this reason, in recent years we have witnessed an increasing reflexivity among IR scholars to incorporate a new agenda for research and to bring other IR perspectives to the center of the stage, different from those imposed from the Anglo-Saxon debates. Thus, many scholars have gathered around the need to outline a global agenda centered on the place that regional and national schools have within the IR field.[63] This attempt has seen only limited efforts within IPE.[64] However, some efforts have been made among scholars in and from the periphery to think IPE differently and bring to light the specificity of the field to think their own realities, understand their own problems and policy challenges, and design their own solutions to them. In this sense, bringing together the way IPE developed in places like Africa, Asia, and South America allows us to search and encourage new channels of dialogue among Global IPE scholars. IPE from the south brings a class relational and inequality perspective that it has been left aside by mainstream debates. The following table compares the way in which IPE has evolved in the three regions explored here, in terms of topics, theoretical approaches, and the main centers that played a key role encouraging the underpinnings of the field.

6. Conclusions

Robert Cox pointed out that “theory is always for someone and for some purpose”. [65] In the case of the regions addressed in this paper we have demonstrated that in IPE, locally grounded theory has sought to speak for excluded and marginalized groups in the case of Africa; Marxism and the state in the case of China; and development and the public sector in Latin America. The main issue is that traditional IPE grounded in the North does not consider these types of debates as part of the IPE field. Given that mercantilism, liberalism and Marxism and its derivatives have been considered as the classic underpinnings of current IPE, most peripheral ideas have been unacknowledged in western IPE debates. For this reason, reflections like the one proposed here are intended to encourage greater reflexivity among IPE scholars in an attempt to incorporate a new agenda for research or to bring alternative IPE perspectives to light. It is with this goal in mind that increasing numbers of scholars have begun gathering around the need to outline a global agenda centered on the place regional and national schools have within the IR and IPE fields.[66]

Proof of the lack of recognition of alternative traditions can be found in Cohen’s recent reedition of his book Advanced Introduction to International Political Economy, in which he diagnoses that the Latin American state of IPE is unproductive, fragile, and anemic; and in which he cites only a few academics in that tradition who have recently published on IPE, selecting mostly those that live and work in the Global North.[67] In the case of China, Cohen, while recognizing that the field is thriving, nevertheless concludes that the field has not managed to provide any transformational contributions. Unfortunately, he does not address at all the state of the field in Africa. In our view, his assessment of IPE has a bias toward recognizing theories that come from the North and neglecting the contribution of IPE from the Global South due to scarce knowledge of how the field is developing in those regions.

Cox has also suggested that one´s orientation towards parts and whole is not so much chosen but acquired through disciplinary socialization,[68] and in this sense, our main aim in this paper has been to call attention to how IPE has developed in three different regions in order to highlight how disciplinary socialization has molded the idiosyncrasy of IPE in those cases. We also disagree with the way mainstream IPE has ignored Global South IPE, particularly sharing with Cohen[69] his concern about the ideas that proclaim a new era of technical sophistication and intellectual elegance coming at the price of descriptive and practical credibility. Peripheral IPE will always be practical and problem-solving given the needs of the countries in which it develops. In this sense, as Narlikar recommends a detailed context-sensitive understanding is key to spark a dialogue about how concepts and ideas travel across regions and cultures expanding the horizon of the IPE field. [70]

Acharya, Amitav. “Global International Relations (IR) and Regional Worlds: A New Agenda for International Studies.” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 4 (2014): 647–59.

Acharya, Amitav, and Barry Buzan, eds. Non-Western International Relations Theory: Perspectives on and beyond Asia. London, UK: Routledge, 2010.

Ake, Claude. “The New World Order: A View from Africa.” In Whose World Order, edited by Hans-henrik Holm, 19–42. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Akinjogbin, Isaac Adeagbo, and Segun Osoba. Topics on Nigerian Economic and Social History. Vol. 2. Nigeria: University of Ife Press, 1980.

Amin, Samir. “Accumulation and Development: A Theoretical Model.” Review of African Political Economy 1, no. 1 (1974): 9–26.

———. Accumulation on a World Scale. Monthly Review Press, 1974.

———. Imperialism and Unequal Development. Hassocks: Haverster Press, 1977.

Battaglino, Jorge M. “Política de defensa y política militar durante el Kirchnerismo.” In La Política En Tiempos de Los Kirchner, by Malamud, Andrés and Miguel Alejandro de Luca (coord.), 241–50. Eudeba, 2012.

Beckman, Björn, and Gbemisola Adeoti. Intellectuals and African Development: Pretension and Resistance in African Politics. London; New York: Zed Books, 2006.

Beigel, Fernanda. The Politics of Academic Autonomy in Latin America. Routledge, 2016.

Bilgin, Pinar. “Thinking Past ‘Western’ IR?” Third World Quarterly 29, no. 1 (2008): 5–23.

Blyth, Mark. “Torn Between Two Lovers? Caught in the Middle of British and American IPE1.” New Political Economy 14, no. 3 (2009): 329–36.

Braz, Adriana Montenegro. “Migration Governance in South America: The Bottom-Up Diffusion of the Residence Agreement of Mercosur.” Revista de Administração Pública 52, no. 2 (2018): 303–20.

Breslin, Shaun. “Beyond the Disciplinary Heartlands: Studying China’s International Political Economy.” In China’s Reforms and International Political Economy, eds. David Zweig and Chen Zhimin, 21–41. London; New York: Routledge, 2007.

Chin, Gregory, Margaret M. Pearson, and Wang Yong. “Introduction–IPE with China’s Characteristics.” Review of International Political Economy 20, no. 6 (2013): 1145–64.

Chodor, Tom, and Anthea McCarthy-Jones. “Post-Liberal Regionalism in Latin America and the Influence of Hugo Chávez.” Journal of Iberian and Latin American Research 19, no. 2 (2013): 211–23.

Cohen, Benjamin J. Advanced International Political Economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019.

———. International Political Economy: An Intellectual History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Cox, Robert W. “Social Forces, States and World Orders: Beyond International Relations Theory.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 10, no. 2 (1981): 126–55.

Dabène, Olivier. “Explaining Latin America’s Fourth Wave of Regionalism Regional Integration of a Third Kind.” Paper presented at LASA Congress, San Francisco, May 25, 2012.

Deciancio, Melisa. “International Relations from the South: A Regional Research Agenda for Global IR.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 106–19.

———. “La economía política internacional en el campo de las relaciones internacionales argentinas.” Desafíos 30, no. 2 (2018): 15–42.

Eagleton-Pierce, Matthew. “Examining the Case for Reflexivity in International Relations: Insights from Bourdieu.” Journal of Critical Globalisation Studies 1, no. 1 (2009): 111–23.

Fan, Yongming. Xifang guoji zhengzhi jingjixue [Western international political economy]. Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin Press, 2001.

Frieden, Jeffry A., and David A. Lake. International Political Economy: Perspectives on Global Power and Wealth. Routledge, 2002.

Gilman, Nils. “The New International Economic Order: A Reintroduction.” Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development 6, no. 1 (2015): 1–16.

Goldsmith, Arthur A. “Foreign Aid and Statehood in Africa.” International Organization 55, no. 1 (2001): 123–48.

Guzzini, Stefano. Realism in International Relations and International Political Economy: The Continuing Story of a Death Foretold. Routledge, 2013.

Helleiner, Eric. “Globalising the Classical Foundations of IPE Thought.” Contexto Internacional 37, no. 3 (2015): 975–1010.

Herrero, María Belén, and Diana Tussie. “Unasur Health: A Quiet Revolution in Health Diplomacy in South America.” Global Social Policy 15, no. 3 (2015): 261–77.

Lavelle, Kathryn. “Moving in from the Periphery: Africa and the Study of International Political Economy.” Review of International Political Economy 12, no. 2 (2005): 364–79.

Legler, Thomas. “Post-Hegemonic Regionalism and Sovereignty in Latin America: Optimists, Skeptics, and an Emerging Research Agenda.” Contexto Internacional 35, no. 2 (December 2013): 325–52.

Narlikar, Amrita. “‘Because They Matter’: Recognise Diversity—Globalise Research.” GIGA Focus Global no. 1 (2016): 1–10.

Nkiwane, Tandeka C. “Africa and International Relations: Regional Lessons for a Global Discourse.” International Political Science Review 22, no. 3 (2001): 279–90.

Nolte, Detlef. “Costs and Benefits of Overlapping Regional Organizations in Latin America: The Case of the OAS and UNASUR.” Latin American Politics and Society 60, no. 1 (2018): 128–53.

Ofuho, Cirino Hiteng. “Africa: Teaching IR Where It’s Not Supposed to Be.” In International Relations Scholarship around the World, by Arlene B. Tickner and Ole Wæver. Routledge, 2009.

Ohiorhenuan, John F.E., and Zoë Keeler. “International Political Economy and African Economic Development: A Survey of Issues and Research Agenda.” Journal of African Economies 17, no. Supplement 1 (2008): 140–239.

Osoba, Segun. “The Deepening Crisis of the Nigerian National Bourgeoisie.” Review of African Political Economy 5, no. 13 (1978): 63–77.

———. “The Dependency Crisis of the Nigerian National Bourgeoisie.” Review of African Political Economy, no. 23 (1978).

Palestini Céspedes, Stefano, and Giovanni Agostinis. “Constructing Regionalism in South America: The Cases of Transport Infrastructure and Energy within UNASUR.” Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Paper No. RSCAS 73 (2014).

Perrotta, Daniela Vanesa. “El campo de estudios de la integración regional y su aporte a las relaciones internacionales: una mirada desde América Latina.” Relaciones Internacionales 38 (2018). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15366/relacionesinternacionales2018.38.001.

Phillips, Nicola, and Catherine Weaver, eds. International Political Economy: Debating the Past, Present, and Future. New York, NY: Routledge, 2011.

Quiliconi, Cintia. “Competitive Diffusion of Trade Agreements in Latin America.” International Studies Review 16, no. 2 (2014): 240–51.

Quiliconi, Cintia, and Renato Rivera Rhon. “Ideology and Leadership in Regional Cooperation: The Cases of Defense and the World Against Drugs Councils in UNASUR.” Revista Uruguaya de Ciencia Política 28, no. 1 (2019): 219–48.

Quiliconi, Cintia, and Raúl Salgado Espinoza. “Latin American Integration: Regionalism à La Carte in a Multipolar World?” Colombia Internacional 92 (2017): 15–41.

Riggirozzi, Pía, and Diana Tussie. “The Rise of Post-Hegemonic Regionalism in Latin America.” In The Rise of Post-Hegemonic Regionalism, edited by Pía Riggirozzi and Diana Tussie, 1–16. (Springer, 2012).

Rodney, Walter. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Verso Trade, 2018.

Sanahuja, José Antonio. “Post-Liberal Regionalism in South America: The Case of UNASUR.” EUI Working Papers RSCAS, No. 2012/05. http://hdl.handle.net/1814/20394.

Schmidt, Brian C. Political Discourse of Anarchy, The: A Disciplinary History of International Relations. Albany: SUNY Press, 2016.

Schulz, Michel, Fredrik Soderbaum, and Joakim Ojendal. Regionalization in a Globalizing World: A Comparative Perspective on Forms, Actors and Processes. London: Zed Books, 2001.

Shaw, Timothy M. “The Political Economy of African International Relations.” Issue: A Journal of Opinion 5, no. 4 (1975): 29–38.

Smith, Karen. “Reshaping International Relations: Theoretical Innovations from Africa.” All Azimuth7, no. 2 (2017): 81–92.

Taylor, Ian, and Paul Williams. Africa in International Politics: External Involvement on the Continent. Routledge, 2004.

Thomas, Caroline, and Peter Wilkin. “Still Waiting after All These Years: ‘The Third World’ on the Periphery of International Relations.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 6, no. 2 (2004): 241–58.

Tickner, Arlene B. “Hearing Latin American Voices in International Relations Studies.” International Studies Perspectives 4, no. 4 (2003): 325–50.

Tickner, Arlene B., and Ole Wæver. International Relations Scholarship Around the World. Routledge, 2009.

Tussie, Diana. “Relaciones Internacionales y Economía Política Internacional: Notas Para El Debate.” Relaciones Internacionales 24, no. 48 (2015). https://revistas.unlp.edu.ar/RRII-IRI/article/view/1457.

———. “The Tailoring of IPE in Latin America: Lost, Misfit or Misperceived?” In Handbook of International Political Economy, edited by Ernesto Vivares. 92-110. Routledge, 2019.

Tussie, Diana, and Pia Riggirozzi. “A Global Conversation: Rethinking IPE in Post-Hegemonic Scenarios.” Contexto Internacional 37, no. 3 (2015): 1041–68.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. “Dependence in an Interdependent World: The Limited Possibilities of Transformation within the Capitalist World Economy.” African Studies Review 17, no. 1 (1974): 1–26.

Wenli, Zhu. “International Political Economy from a Chinese Angle.” Journal of Contemporary China 10, no. 26 (2001): 45–54.

Xinning, Song. “Building International Relations Theory with Chinese Characteristics.” Journal of Contemporary China 10, no. 26 (2001): 61–74.

Xinning, Song, and Chen Yue. Introduction to International Political Economy. Beijing: Renmin University Press, 1999.

Zweig, David, and Zhimin Chen. “Introduction: International Political Economy and Explanations of China’s Globalization.” In China’s Reforms and International Political Economy, eds. David Zweig and Chen Zhimin, 42–61. London; New York: Routledge, 2007.