Ali Bakir

Qatar University

Eyüp Ersoy

King’s College London

Asymmetry of knowledge production in global international relations manifests itself in a variety of forms. Concept cultivation is a foundational form that conditions the epistemic hierarchies prevalent in scholarly encounters, exchanges, and productions. The core represents the seemingly natural ecology of concept cultivation, while the periphery appropriates the cultivated concepts, relinquishing any claim of authenticity and indigeneity in the process. Nonetheless, there have been cases of intellectual undertakings in the periphery to conceive, formulate, and articulate conceptual frames of knowledge production. This paper, first, discusses the fluctuating fortunes of homegrown concepts in the peripheral epistemic ecologies. Second, it introduces the concept of ‘strategic depth’ as articulated by the Turkish scholar Ahmet Davutoğlu and reviews its significance for the formulation and implementation of recent Turkish foreign policy. Third, it examines the causes of its recognition and acclaim in the local and global IR communities subsequent to its inception. The paper contends that there have been three fundamental sets of causes for the initial ascendancy of the concept. These are categorized as contemplative causes, implementative causes, and evaluative causes. Fourth, it traces the sources of its fall from scholarly grace. The paper further asserts that the three fundamental sets of causes were also operational in the eventual conceptual insolvency of strategic depth. The paper concludes by addressing remedial measures to vivify concept cultivation in the periphery and to conserve the cultivated concepts.

1. Introduction

Asymmetry of knowledge production in global international relations manifests itself in various forms. Concept cultivation is a foundational form that conditions the epistemic hierarchies prevalent in scholarly encounters, exchanges, and productions. The core represents the seemingly natural ecology of concept cultivation, while the periphery appropriates the cultivated concepts, relinquishing any claim of authenticity and indigeneity in the process.[1] Nonetheless, there have been cases of intellectual undertakings in the periphery to conceive, formulate, and articulate conceptual frames of knowledge production. The concept of ‘strategic depth’ propounded by the Turkish scholar Ahmet Davutoğlu exemplifies the attempts of local epistemic communities to overcome the conceptual marginalization they are subjected to through the cultivation of homegrown concepts.

This paper, first, discusses the fluctuating fortunes of homegrown concepts in the peripheral epistemic ecologies. Second, it introduces the concept of ‘strategic depth’ as articulated by Ahmet Davutoğlu and reviews its significance for the formulation and implementation of recent Turkish foreign policy. Third, it examines the causes of its recognition and acclaim in the local and global IR communities subsequent to its inception. The paper contends that there have been three fundamental sets of causes for the initial ascendancy of the concept. These are categorized as contemplative causes, implementative causes, and evaluative causes. Fourth, it traces the sources of its fall from scholarly grace. The paper further asserts that the three fundamental sets of causes were also operational in the eventual conceptual insolvency of strategic depth. The paper concludes by addressing remedial measures to vivify concept cultivation in the periphery and to conserve the cultivated concepts.

2. The Rise and Fall of Homegrown Concepts in Global IR

Thanks to a combination of material shifts in the global distribution of power and ideational transformations in approaches to the study of international affairs, once-marginalized peripheral knowledge production has increased in vitality, maturity, and productivity.[2] An integral element of peripheral knowledge production is the cultivation of homegrown concepts, frequently accompanied by “a self-reflexive process of exploring and exploiting native conceptual resources.”[3] Accordingly, a great many concepts that originated in peripheral academia have been introduced in the disciplinary progression of international relations. A recent example is the concept of ‘relationality.’ Developed by the Chinese scholar Yaqing Qin, relationality draws on “the Confucian cultural community over millennia,” and “conceives the world of IR as one composed of ongoing relations rather than discrete individual entities, assumes international actors as actors-in-relations, and takes processes defined in terms of relations in motion as ontologically significant.”[4] Since its inception, relationality has elicited a good deal of sustained academic interest.[5]

Still, in many cases, following the initial ascendancy, homegrown concepts have failed to sustain their disciplinary appeal. While the pattern of the rise and fall of homegrown concepts is observable in these cases, depending on specific circumstances, the life cycle of indigenous conceptual innovations varies in duration. As one of the most influential and resilient homegrown concepts in international relations, ‘dependencia/dependency’ is illustrative of the fluctuating fortunes of peripheral disciplinary interventions.

In the wake of the Second World War, dependency was reconceived in the context of Latin America by local scholars to account for the structural dynamics and debilitating effects of the global political economy on the states and peoples of the region. Based on a novel reinterpretation of dependency, Brazilian scholar Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Chilean scholar Enzo Faletto “developed an original theory of international relations with a specific analytical version of a world order that accounts for an alternative and nuanced version of North–South relations in terms of the international political economy.”[6] Their work was to become a seminal text in the canon of the dependency theory of international political economy.[7] Dependency theory has been “touted as the one authentically peripheral formula for confronting problems of development and global insertion.”[8]

The concept, and the theory, initially achieved widespread disciplinary recognition manifested in insightful intellectual engagements both in the periphery and the core.[9] This peripheral theoretical perspective was also subject to severe criticism, especially from the core. As an example, according to Stanley Hoffmann, if established elites in the developing countries “that are eager to boost national power against foreign dominance” were to “follow the advice of ‘dependencia’ theorists, the result is not likely to be a world of peace and justice, but a world of revolutions, and new conflicts, and new inequities.”[10]

Nonetheless, in subsequent decades, dependency as a concept and as a theory has progressively become marginalized in the discipline. One practical reason, it can be asserted, is the substantial economic growth experienced by several developing countries, especially in Asia, in contrast to the prognoses of the theory. Ultimately, despite the foundational role of several Brazilian scholars, such as Fernando Cardoso, Celso Furtado, and Ruy Marini, dependency theory has come to occupy only a marginal position within Brazilian IR itself.[11] A similar trend has taken place in the core as well. For instance, in recent disciplinary history, “for a brief time, the Dependencia tradition from Latin America [has] been actively engaged by U.S. scholars in leading research departments,” and today “like the other works in the radical tradition, the dependency approach is no longer assigned in any of the top ten departments [in the US].”[12]

3. A Homegrown Concept in Turkish IR: Strategic Depth

The last two decades have witnessed a similar pattern of the rise and fall of homegrown concepts in Turkey. The concept of ‘strategic depth’ that was introduced by Turkish scholar Ahmet Davutoğlu in 2001 in an eponymous book, Strategic Depth, received extensive interest both intellectually and politically in national and, to some extent, international settings.[13] However, after a decade of analytical popularity, scholarly attention towards strategic depth has transformed substantially. Originally developed in military studies and referred to habitually in strategic studies and security studies,[14] strategic depth was redefined by Davutoğlu to construct an all-embracing metanarrative of Turkish foreign policy.

and “geostrategic” pillars

Davutoğlu received his PhD in comparative political theory, and prior to his entry into practical politics, he was an accomplished university professor and intellectual.[15] Davutoğlu was to become an ‘intellectual of statecraft,’ that is, a member of a “community of state bureaucrats, leaders, foreign-policy experts and advisors throughout the world who comment upon, influence and conduct the activities of statecraft,” when he began his political career in 2003 as the chief advisor to the Turkish Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.[16] Davutoğlu was promoted to Minister of Foreign Affairs in May 2009, and served until August 2014, when he became the Prime Minister of Turkey. Davutoğlu was to resign from his post in May 2016 only to launch his political party in December 2019.[17]

Ahmet Davutoğlu articulated a novel assessment of Turkish foreign policy encapsulated in the concept of strategic depth for the incremental expansion of Turkey’s influence in designated geopolitical areas called territorial, maritime, and continental basins.[18] In this exposition, strategic depth is comprised of geographical depth and historical depth. Drawing on the perceived opportunities provided by Turkey’s geographical environment and historical engagement, strategic depth was expected to constitute the foundation for the emerging agency of Turkey in global politics.[19] Multiple dimensions of this new geopolitical vision were elaborated in complementary publications by Davutoğlu subsequent to Strategic Depth in 2001.[20] Ahmet Davutoğlu’s book has become a seminal text in the analytical discussions and polemical debates on the notion of strategic depth. The book was referred to, in a somewhat sympathetic collection of essays on Ahmet Davutoğlu and strategic depth, as “a founding text,”[21] and “the book still the most comprehensive and the richest in content which determines the strategy for Turkish foreign policy.”[22] In brief, the book has been perceived as advancing an alternative and ambitious paradigm for the imagination and implementation of Turkish foreign policy.[23]

4. A Homegrown Concept in Turkish IR: Strategic Depth

After its publication in April 2001, Strategic Depth rapidly captured the interest of academia as well as the general public opinion, turning into an indispensable reference in studies of Turkish foreign policy. As of March 2021, the book has recorded 121 editions, an unprecedented figure for a scholarly book in Turkey.[24] Though Strategic Depth has yet to be translated into English at the explicit request of its author,[25] the book has reached a broader international audience through its translations into multiple languages, including Albanian, Arabic, Bulgarian, Greek, Hungarian, Japanese, Persian, Russian, and Serbian.[26] The book also has Wikipedia entries in Arabic and Armenian, besides Turkish. Since its appearance, scholarly studies referring to strategic depth in relation to Turkish foreign policy have proliferated.[27]

There have been three fundamental sets of causes for the initial ascendancy of the concept. These can be categorized as contemplative causes, implementative causes, and evaluative causes. Contemplative causes are pertinent to the substance and the argumentation of strategic depth. First and foremost, strategic depth signifies a compelling alternative discourse on Turkish foreign policy predicated on quite systematic and coherent reasoning with new postulations, assumptions, and conclusions. Strategic depth represents a novel geopolitical imagination in Turkish foreign policy that entails, and in fact calls for, dynamism, activism, ambition, and expansion.[29] In its final paragraph, Strategic Depth highlights Turkey’s “responsibility to form a new and meaningful whole between its historical depth and strategic depth, and to actualize this whole within the geographical depth.”[30] In a similar vein, strategic depth has purported to construct a new identity for Turkey in global affairs, and thereby transcend dichotomous self-representations that have afflicted the Turkish mindset, arguably suffering from a self-induced cognitive dissonance.[31] According to Strategic Depth, in contrast to societies enduring “identity distress,” only those societies “that have a strong sense of identity and belonging stemming from a common time-space consciousness and that can mobilize psychological, sociological, political, [and] economic elements with this sense” can perform “constantly renewable strategic openings.”[32]

Implementative causes are pertinent to the application of strategic depth, both in style and in substance, in Turkish foreign policy. In general, Turkish foreign policy during the tenure of Ahmet Davutoğlu as the chief foreign policy advisor, and especially as foreign minister, was characterized by an unusual degree of activism.[33] For some observers, strategic depth represented a source of epiphany after decades of insouciant apathy in Turkish foreign policy.[34] According to the director of the Office of Public Diplomacy in Turkey at the time, “the recent activism in Turkish foreign policy…[was] driven largely by a concern to create an orderly political environment in which it is easier to address pressing issues in Turkey’s immediate neighbourhood while also turning Turkey into a major powerhouse in the region.”[35]

One dimension of this new activism concerned a multidimensional approach to foreign policy. For example, a commentator stated in 2010 that “the sheer number and level of visits to and from neighbouring countries [was] a clear indicator of the new activism vis-à-vis Turkey’s neighbourhood. From Moscow to Tehran, from Athens to Baghdad and Damascus, from Belgrade to Beirut, Turkey [was] engaged in a very proactive outreach.”[36] Others were explicit in attributing the sources of this multidimensional activism to strategic depth as it was asserted that the Justice and Development Party (JDP) government’s “multidimensional approach to foreign policy was very much influenced by Ahmet Davutoğlu’s ‘strategic depth’ perspective.”[37] The argument here is not that this unusual activism in Turkish foreign policy was unanimously identified as an auspicious development.[38] It is contended, rather, that the motives to make sense of this unusual degree of activism culminated in a growing interest in strategic depth that was generally conceived to have imparted a new ethos to Turkish foreign policy.[39]

Evaluative causes are pertinent to the factors that condition the assessments of the thought and practice of strategic depth. On the articulation of strategic depth, one conditioning parameter has been the ideological orientation of the discursive framework wherein the concept is devised. Strategic depth did advance a reasonably cogent alternative to the prevalent narratives about Turkish foreign policy with distinct ideological underpinnings. One observer noted that there had been three different geopolitical imaginations with paradigmatic pretensions in Turkey, which were Kemalist geopolitics, Turkist-nationalist geopolitics, and Islamist-conservative geopolitics. Strategic Depth, it is further claimed, is “a geopolitical text that is both the source and the agent of the discursive constitution of” the Islamist-conservative geopolitical imagination in Turkey.[40] Among the ‘identity actors’ in Turkish foreign policy, Hasan Kösebalaban subsumed strategic depth under Islamic liberalism.[41] Accordingly, strategic depth captivated the attention of conservative intelligentsia immediately after its inception.

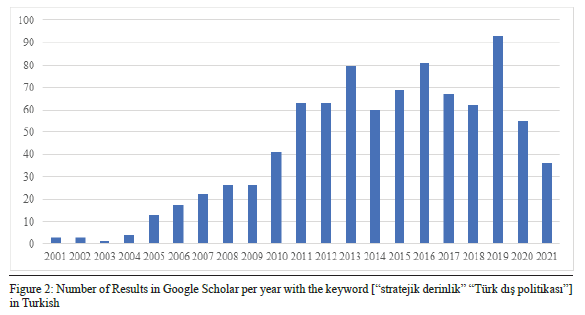

On the implementation of strategic depth, two critical junctures proved to be momentous. The first one was the advent of a single-party government in 2003, two years after the publication of Strategic Depth, whose ideological orientation was congruous with the premises and the dictates of the new foreign policy approach put forward in the book. As a counterfactual, without the JDP coming to power in November 2002, strategic depth would not have been subjected to the same level of analytical scrutiny. The second pivotal moment was the promotion of Ahmet Davutoğlu from the chief foreign policy adviser to the foreign minister in May 2009. This has created a practical necessity for scholars and policy analysts alike to reflect more scrupulously upon the opinions and intentions of the person customarily dubbed as ‘the architect’ of new Turkish foreign policy. [42] The proliferation of scholarly publications referring to strategic depth after 2009 in the abovementioned graphs can be explained, in part, with reference to the growing interest in the worldview of this “energetic foreign minister.”[43]

In particular, the rapid rapprochement observed in Turkey’s relations with Syria after 2003 appeared as a veritable vindication of the promise of strategic depth at the time. While the unresolved disputes brought the two states to the very brink of war in 1998,[44] bilateral relations reached an advanced level in the ensuing period. In 2007, Ahmet Davutoğlu declared that “in contrast to that of 5-10 years ago, Turkey’s level of relations with Syria today [stood] as a model of progress for the rest of the region.”[45] In September 2009, visa liberalization was announced between the two countries, and the inaugural meeting of the high-level strategic cooperation council convened in Damascus three months later.[46] In Syria, Turkey was also seen as “the most likely place” for “a reasonably free, democratic and secular model that works in a Muslim society.”[47] Those were the “years of euphoria” in Turkey’s relations with Syria.[48]

5. A Homegrown Concept in Turkish IR: Strategic Depth

Over the course of the last decade, despite initial conceptual celebrity, strategic depth has fallen from scholarly grace. This has not been a descent in quantitative terms, though, as the number of scholarly publications continues to reveal an enduring interest in strategic depth.[49] Strategic depth has fallen in credibility as an analytical framework, as well as a practical template for Turkish foreign policy. Worse, the concept has become a target of vindictive animadversions, and on some occasions, a victim of denigrating ridicule. There have been three fundamental sets of causes for the ultimate downfall of the concept.

In terms of contemplative causes, several critiques have addressed perceived deficiencies in the conception and argumentation of strategic depth. It is argued, for instance, that

…“historical” and “geostrategic” pillars [of strategic depth] are informed by a certain conservative communitarianism on the one hand, and interest-maximizing opportunism on the other. Since the Foreign Minister sensibly downplays the former, given the great diversity, complexity, and sensitivity of Turkey and its neighborhoods, and since the latter is effectively amoral, the “strategic depth” doctrine lacks normative traction. Therefore, it has been only partially successful in capturing the imagination of those within and beyond Turkey.[50]

One possible criticism involves the conception of ‘history’ in strategic depth. History is constitutive of the analytical framework propounded by Ahmet Davutoğlu as Strategic Depth is replete with references to historical consciousness, historical alienation, historical memory, historical legacy, de-historicization, and above all, historical depth.[51] In Davutoğlu’s view, as an example, “societies’ perceptions of space which take their own geographical locations as the axis, and their perceptions of time which take their own historical experiences as the axis constitute the infrastructure of the mindset that influence [foreign policy?] orientations and foreign policymaking.”[52] Furthermore, in this historical experience, the Ottoman Empire occupies a magisterial position, and represents more than a political entity. Turkey, to quote Davutoğlu, “is the center of a civilization [qua the Ottoman Empire] that established a unique and long-lasting political order in the past, which also comprised the intersection points of the world main landmass.”[53]

Notwithstanding, as one of the ironies of strategic depth, the concept would not have constituted a point of departure for the Ottoman Empire insofar as for the Ottoman Empire, there had been no previous Ottoman Empire. That is, for the Ottoman Empire, for its foreign policy elites and the intelligentsia, there was no previous historical experience to draw on, and there was no historical depth to capitalize upon. All the strategic depth the Ottoman Empire used to possess, it created on its own by persevering through challenges.[54] For the Ottoman Empire, strategic depth was something to be constituted prospectively. On the other hand, in Ahmet Davutoğlu’s formulation, strategic depth is conceived as something to be restituted retrospectively. This is a significant difference between the historical experience of the Ottoman Empire and the interpretation of this experience in Strategic Depth.

In terms of implementative causes, the loss of credibility for strategic depth lies in its analytical utility, explanatory value, and prescriptive capacity becoming contingent upon its practicality. In general, concepts can be controverted and invalidated by state of affairs evolving in the absence of direct involvement of those that formulate and promote them. In the case of strategic depth, however, Ahmet Davutoğlu’s unmediated position in the execution of the concept he had systematized exacerbated the tragic fall of strategic depth. Davutoğlu’s propensity to relate his theory to his practice further solidified the association between the credibility of strategic depth and the practical performance of its implementation.[55] His grandiloquent discourse did not help, either. In the immediate aftermath of his promotion to foreign minister, for example, Davutoğlu declared that “no development takes place in the surrounding regions at the moment without the will, knowledge, and approval of Turkey. God willing, when we celebrate the centenary of the Republic, nothing will take place in the world without the approval and knowledge of Turkey.”[56]

In defiance of self-assured statements, the evolution of Turkish foreign policy in the ensuing period was to bring about a good deal of disillusionment with strategic depth. This disillusionment can be traced in the eventual realization of the five principles of ‘Turkey’s new foreign policy’ elaborated by Ahmet Davutoğlu in 2008.[57] These were balance between security and democracy, zero problem policy towards neighbors, developing relations with neighboring regions, multi-dimensional foreign policy, and rhythmic diplomacy.[58] Concerning the first principle, as an example, Davutoğlu was of the opinion that “if there is not a balance between security and democracy in a country, it may not have a chance to establish an area of influence in its environs,” and “Turkey’s most important soft power is its democracy.”[59]

Concurring with Davutoğlu, another influential figure made a similar claim that “one of the basic footholds of Turkey’s soft power is its democracy experience,” and “the gradual institutionalization of democracy day by day and strengthening of its legitimacy among the public is at the forefront of the dynamics that ensure Turkey’s becoming a regional and global actor.”[60] Nonetheless, a critical assessment that “the later phase of the AKP [JDP] era is a kind of limited or majoritarian understanding of democracy with new elements of exclusion built into the democratic system” was to be vindicated by later developments that severely undermined Turkey’s democratic credentials.[61] In 2016, the year Davutoğlu left office, Turkey was ranked 97th among 167 countries in the world in terms of the state of its democracy.[62] And the same year, Freedom House identified Turkey as ‘partly free.’[63]

In particular, the eruption of the Arab uprisings in 2011, especially in Syria, and the ensuing tragic course of events caught Ahmet Davutoğlu, the foreign minister, by surprise, and yet he approached the developments with unwarranted overconfidence and a propensity to take undue risks.[64] These events exposed the shortcomings and limitations of strategic depth, and revealed that it was not well equipped to face the new geopolitical realities including scenarios of a regime change in Syria.[65] As a result, Turkey has suffered, and continues to do so, in many ways and in many forms, from the adverse ramifications of the developments in Syria.[66] In the end, strategic depth has become a conceptual collateral damage of the Syrian civil war.

In terms of evaluative causes, politicization of the intellectual life and the concomitant epistemic polarization appear to have conditioned the assessments of the thought and practice of strategic depth. In general, politicization can take two primary forms. First, the concept itself can be politicized, and second, the individual(s) that have cultivated the concept can be politicized. In a concept’s ultimate loss of credibility, contemplative causes and implementative causes are necessary causes, but not sufficient ones. That is, a concept with weak contemplation and ineffective implementation can still be subject to non-partisan scholarly engagements, and in a non-politicized, non-polarized intellectual setting, a dynamic and productive debate can still arise about the relative merits of the concept. Nevertheless, politicization and polarization foreclose, or at least compromise, this potentiality, and instead pave the way for categorized factional approaches to the concept between its proponents and its opponents.

For proponents of strategic depth, the lack of detached assessments of the underlying premises of the concept has impaired its cultivation. One premise concerns the historical underpinnings of strategic depth. History is not just an analytical category in strategic depth, but constitutive of an identity. Thus, conception of history becomes construction of identity, and an examination of the function of history in the construction of strategic depth is perceived as subversive to the imagined identity by proponents of the concept. As a result, any analytical discussion of strategic depth is prone to beget existential disputation. Besides, Turkey, as a post-imperial nation-state, has its own shadow, i.e., the Ottoman Empire. Proponents of strategic depth in Turkey seem to bear an innate temptation to look at the shadow of the past to appraise the thought and practice of the concept. Contrary to the impulsion of the proponents of strategic depth to cast the light of the luminous history on the concept, strategic depth has remained in the twilight of the past. Conceptual defeat is an orphan as well, and today strategic depth is mostly forsaken by its former proponents.

On account of the politicization of strategic depth, two groups of opponents have emerged. For the political opponents, political affiliation of Ahmet Davutoğlu has converted the concept into a target of political rivalry. As an example, identifying Ahmet Davutoğlu with the concept, the leader of the Nationalist Action Party (MHP) scolded the formation of a new political party by Davutoğlu, arguing that “the claims of strategic pits [stratejik çukurlar] to future are a vain objective, [and] an abortive effort.”[67] During the tenure of Ahmet Davutoğlu as the foreign minister and prime minister, strategic depth was persistently denounced by members of the opposition parties in the parliamentary debates at the Turkish Grand National Assembly (TBMM). For example, it was described as a black hole, political blindness, bottomless well, strategic pit, strategic catastrophe, world of dreams, strategic quagmire, and strategic rout, among others.[68]

For the intellectual opponents of strategic depth, one analytical impediment arguably pertains to the construction of a particular identity through the concept, and trenchant criticisms of strategic depth are perceived as subversive to the imagined identity. Hence, different framing strategies for identity subversion are employed in analyses of strategic depth. One framing strategy depicts strategic depth within the discursive framework of neo-Ottomanism.[69] Another framing strategy portrays the concept within the discursive framework of Islamism/Pan-Islamism.[70] One observer asserted, for instance, that “strategic depth offers a new ‘geopolitical discourse’ about Turkey’s position in the world system that represents a secularized form of Islamic politics oriented towards increasing the power of Turkey in those regions with which it had close ties historically during the Ottoman Empire.”[71]

6. Conclusion: The Rise and Fall of Homegrown Concepts in Global IR

Asymmetry in concept cultivation between the core and the periphery in global IR is a foundational manifestation of the asymmetry of knowledge production in the discipline. Still, the discipline continues to witness the conception, formulation, and articulation of conceptual frames of knowledge production originating in peripheral epistemic communities. The concept of ‘strategic depth’ propounded by the Turkish scholar Ahmet Davutoğlu constitutes one of the contemporary attempts to rectify the disciplinary imbalance through the cultivation of homegrown concepts.[72] Following its inception, strategic depth initially attracted a great deal of recognition and acclaim in the local and global IR communities. Ultimately, though, it has fallen from scholarly grace since the concept has virtually lost its credibility as an analytical framework and a practical template for Turkish foreign policy.

Accordingly, strategic depth is emblematic of the fluctuating fortunes of homegrown concepts in the peripheral epistemic ecologies. There have been three fundamental sets of causes for the initial ascendancy of strategic depth as well as its eventual conceptual insolvency, which are categorized as contemplative causes, implementative causes, and evaluative causes. Remedial measures to vivify concept cultivation in the periphery and to conserve the cultivated concepts need to address these sets of causes underlying the rise and fall of homegrown concepts in global IR. The case of strategic depth bears many lessons in this regard.

In terms of contemplative causes, for example, perceived deficiencies in the conception and argumentation of a homegrown concept do not necessarily constitute a serious impediment to its disciplinary recognition on the condition that it is subjected to serious and persistent scholarly inquiry by the local IR community. Homegrown concepts sustain their analytical relevance only if they are subjected to collective cultivation by local epistemic communities in peripheral contexts. As relatively successful cases of peripheral concept cultivation in the discipline, dependencia and eurasianism are both based on the works of a great many scholars representing collective scholarly undertakings.[73] In the case of strategic depth, the construction of the concept has arguably remained the undertaking of a single scholar, even though strategic depth continues to be subjected to critical conceptual deconstructions.

In terms of implementative causes, an intimate association of the analytical utility, explanatory value, and prescriptive capacity of strategic depth with its practicality has proven to be a blessing and a curse. Most cases of peripheral conceptual cultivation in global IR convey the same association. Practical applicability of homegrown concepts is conceived to buttress their conceptual validity. Nonetheless, as a corollary, unexpected turns of events in foreign policy or inadvertent consequences of certain policies are equally conceived to undermine the validity of homegrown concepts. In the end, conceptual cultivation is taken hostage by practical implementation. In the Turkish case, the fateful execution of the strategic depth doctrine has condemned the concept of strategic depth.

In terms of evaluative causes, to repeat, a homegrown concept with weak contemplation and ineffective implementation can still be subject to non-partisan scholarly engagements. In a non-politicized, non-polarized intellectual setting, a dynamic and productive debate can still arise about the relative merits of the concept. Notwithstanding, in the case of strategic depth, politicization of the concept and polarization of the local epistemic community has precluded detached and creative assessments of the thought and practice of the concept. In peripheral disciplinary contexts in global IR, politicization and polarization plague cultivation of homegrown concepts, forbidding them from flourishing or withering them away.

Acharya, Amitav, and Barry Buzan. The Making of Global International Relations: Origins and Evolution of IR at Its Centenary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Al-Azm, Sadik J. “The ‘Turkish Model’: A View from Damascus.” Turkish Studies 12, no. 4 (2011): 633–41.

Alejandro, Audrey. Western Dominance in International Relations? The Internationalization of IR in Brazil and India. Oxon: Routledge, 2019.

Aras, Bülent. “The Davutoğlu Era in Turkish Foreign Policy.” Insight Turkey 11, no. 3 (2009): 127–42.

Aras, Bülent, and Hakan Fidan. “Turkey and Eurasia: Frontiers of a New Geographical Imagination.” New Perspectives on Turkey 40 (2009): 193–215.

Aras, Damla. “Similar Strategies, Dissimilar Outcomes: Appraising of the Efficacy of Turkey’s Coercive Diplomacy with Syria and in Northern Iraq.” Journal of Strategic Studies 34, no. 4 (2011): 587–618.

Aydınlı, Ersel, and Julie Mathews. “Periphery Theorising for a Truly Internationalised Discipline: Spinning IR Theory out of Anatolia.” Review of International Studies 34, no. 4 (2008): 693–712.

Bakir, Ali. “Determinants of the Turkish Position towards the Syrian Crisis: Immediate Dimensions and Future Repercussions.” Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, June 2011. https://www.dohainstitute.org/ar/lists/ACRPS-PDFDocumentLibrary/document_6BF7FC4E.pdf [in Arabic].

Başkan, Birol. “Islamism and Turkey’s Foreign Policy during the Arab Spring.” Turkish Studies 19, no. 2 (2018): 264–88.

Bassin, Mark, Sergey Glebov, and Marlene Laruelle, eds. Between Europe and Asia: The Origins, Theories, and Legacies of Russian Eurasianism. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015.

Biersteker, Thomas J. “The Parochialism of Hegemony: Challenges for ‘American’ International Relations.” In International Relations Scholarship around the World, edited by Arlene B. Tickner and Ole Waever, 308–27. Oxon: Routledge, 2009.

Cagaptay, Soner. Erdogan’s Empire: Turkey and the Politics of the Middle East. New York: I. B. Tauris, 2020.

Caporaso, James A. “Dependence, Dependency, and Power in the Global System: A Structural and Behavioral Analysis.” International Organization 32, no. 1 (1978): 13–43.

Cardoso, Fernando Henrique, and Enzo Faletto, Dependencia y Desarrollo en América Latina: Ensayo de Interpretación Sociológica. Sa: Siglo Veintiuno Editores, 1971.

Çapan, Zeynep Gülsah, and Ayşe Zarakol. “Turkey’s Ambivalent Self: Ontological Insecurity in ‘Kemalism’ and ‘Erdoğanism’.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 32, no. 3 (2019): 263–82.

Davutoglu, Ahmet. Alternative Paradigms: The Impact of Islamic and Western Weltanschauungs on Political Theory. Maryland: University Press of America, 1994.

–––. Küresel bunalım [Global Angst] İstanbul: Küre Yayınları, 2002.

–––. Stratejik derinlik: Türkiye’nin uluslararası konumu [Strategic Depth: Turkey’s International Position] İstanbul: Küre Yayınları, 2001.

–––. Teoriden pratiğe: Türk dış politikası üzerine konuşmalar [From Theory to Practice: Conversations on Turkish Foreign Policy] İstanbul: Küre Yayınları, 2011.

–––. “Turkey’s Foreign Policy Vision: An Assessment of 2007.” Insight Turkey 10, no. 1 (2008): 77–96.

Demir, Imran. Overconfidence and Risk Taking in Foreign Policy Decision Making: The Case of Turkey’s Syria Policy. Cham: Routledge, 2017.

Duvall, Raymond D. “Dependence and Dependencia Theory: Notes toward Precision of Concept and Argument.” International Organization 32, no. 1 (1978): 51–78.

Ersoy, Eyüp. “Conceptual Cultivation and Homegrown Theorizing: The case of/for the Concept of Influence.” In Widening the World of International Relations: Homegrown Theorizing, edited by Ersel Aydınlı and Gonca Biltekin, 204–25. Oxon: Routledge, 2018.

Fisher Onar, Nora. “‘Democratic Depth’: The Missing Ingredient in Turkey’s Domestic/Foreign Policy Nexus?” In Another Empire? A Decade of Turkey’s Foreign Policy under the Justice and Development Party, edited by Kerem Öktem, Ayşe Kadıoğlu, and Mehmet Karlı, 61–75. İstanbul: İstanbul Bilgi University Press, 2009.

Fravel, M. Taylor. “China’s Search for Military Power.” Washington Quarterly 31, no. 3 (2008): 125–41.

Golmohammadi, Vali, Sayyed Muhammad-Kazem Sajjadpour, and Massoud Mousavi Shefaee. “Erdoganism and Understanding Turkey’s Middle East Policy.” Strategic Studies Quarterly 19, no. 3 (2016): 69–92. [in Persian].

Gözaydın, İştar. “Ahmet Davutoğlu: Role as an Islamic Scholar Shaping Turkey’s Foreign Policy. ” In International Relations and Islam: Diverse Perspectives, edited by Nassef Manabilang Adiong, 91–109. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013.

Groc, Gérard. “La doctrine Davutoglu: une projection diplomatique de la Turquie sur son environnement [Davutoglu Doctrine: Turkey’s Diplomatic Projection on Its Environment].” Confluences Méditerranée no. 83 (2012): 71–85.

Gürzel, Aylin, and Eyüp Ersoy. “From Regionalism to Realpolitik: The Rise and Fall of Turkey as a Middle Power in the Middle East.” in Middle Powers in Asia and Europe in the 21st Century, edited by Giampiero Giacomello and Bertjan Verbeek, 119–36. Maryland: Lexington Books, 2020.

Han, Ahmet K. “Paradise Lost: A Neoclassical Realist Analysis of Turkish Foreign Policy and the Case of Turkish-Syrian Relations.” In Turkey-Syria Relations: Between Enmity and Amity, edited by Raymond Hinnebusch and Özlem Tür, 55–69. Oxon: Routledge, 2013.

Hashmetzadeh, Muhammad Baker, Hamidreza Hamidfar, and Yasir Gaimee. “Strategy of Iran and Turkey in Crisis Management in the Region of West Asia: Case Study of the Syrian Crisis.” [Journal of Politics and International Relations] 4, no. 8 (2020-2021): 29–49. [in Persian].

Hellmann, Gunther, and Morten Valbjørn. “Problematizing Global Challenges: Recalibrating the ‘Inter’ in IR-Theory.” International Studies Review 19, no. 2 (2017): 279–309.

Ho, Tze Ern. “The Relational-Turn in International Relations Theory: Bringing Chinese Ideas into Mainstream International Relations Scholarship.” American Journal of Chinese Studies 26, no. 2 (2019): 91–106.

Hoffmann, Stanley. “An American Social Science: International Relations.” Daedalus 106, no. 3 (1977): 41–60.

İnalcik, Halil. The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300-1600. London: Phoenix, 1973.

Jabbour, Jana. “Le retour de la Turquie en Méditerranée: La ‘profondeur stratégique’ Turque en Méditerranée pré- et post-printemps Arabe [Turkey’s Return to the Mediterranean: Turkish ‘Strategic Depth’ in the Mediterranean Pre- and Post-Arab Spring].” Cahiers de la Méditerranée no. 89 (2014): 45–56.

Kalın, İbrahim. “Debating Turkey in the Middle East: The Dawn of a New Geo-Political Imagination.” Insight Turkey 11, no. 1 (2009): 83–96.

–––.“Turkish Foreign Policy: Framework, Values, and Mechanisms.” International Journal 6, no. 1 (2011-2012): 7–21.

–––. “Türk dış politikası ve kamu diplomasisi.” In MUSIAD araştırma raporları: yükselen değer Türkiye, edited by Ali Resul Usul, 49–65. İstanbul: Mavi Ofset, 2010.

Kacowicz, Arie M., and Daniel F. Wajner, “Alternative World Orders in an Age of Globalization: Latin American Scenarios and Responses.” In Latin America in Global International Relations, edited by Amitav Acharya, Melisa Deciancio, and Diana Tussie, 11–30. Oxon: Routledge, 2022.

Kınıklıoğlu, Suat. “Turkey’s Neighbourhood and Beyond: Tectonic Transformation at Work?” International Spectator 45, no. 4 (2010): 93–100.

Kıvanç, Ümit. Pan-İslamcının macera kılavuzu: Davutoğlu ne diyor, bir şey diyor mu? [Pan-Islamist’s Guide of Adventure: What is Davutoğlu Saying, Is he Saying Anything?] İstanbul: Birikim Yayınları, 2015.

Köse, Talha, Ahmet Okumuş, and Burhanettin Duran, eds. Stratejik zihniyet: kuramdan eyleme Ahmet Davutoğlu ve stratejik derinlik [Strategic Mindset: Ahmet Davutoğlu from Theory to Practice and Strategic Depth] İstanbul: Küre Yayınları, 2014.

Kösebalaban, Hasan. “Torn Identities and Foreign Policy: The Case of Japan and Turkey.” Insight Turkey 10, no. 1 (2008): 5–30.

–––. “Transformation of Turkish Foreign Policy towards Syria.” Middle East Critique 29, no. 3 (2020): 335–44.

–––. Turkish Foreign Policy: Islam, Nationalism, and Globalization. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Kristensen, Peter Marcus. “The BRICs and Knowledge Production in International Relations,” in The International Political Economy of the BRICs, edited by Li Xing, 18–36. Oxon: Routledge, 2019.

Larrabee, F. Stephen. “Turkey’s New Geopolitics.” Survival 52, no. 2 (2010): 157–80.

Mäkinen, Sirke. “Professional Geopolitics as an Ideal: Roles of Geopolitics in Russia.” International Studies Perspectives 18, no. 3 (2017): 288–303.

Meininghaus, Esther, and Carina Schlüsing. “War in Syria: The Translocal Dimension of Fighter Mobilization.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 31, no. 3 (2020): 475–510.

Meral, Ziya, and Jonathan Paris. “Decoding Turkish Foreign Policy Hyperactivity.” The Washington Quarterly 33, no. 4 (2010): 75–86.

Murinson, Alexander. “The Strategic Depth Doctrine of Turkish Foreign Policy.” Middle Eastern Studies 42, no. 6 (2006): 945–64.

Nordin, Astrid H. M., Graham M. Smith, Raoul Bunskoek, Chiung-chiu Huang, Yih-jye (Jay) Hwang, Patrick Thaddeus Jackson, Emilian Kavalski, L. H. M. Ling, Leigh Martindale, Mari Nakamura, Daniel Nexon, Laura Premack, Yaqing Qin, Chih-yu Shih, David Tyfield, Emma Williams and Marysia Zalewski.“Towards Global Relational Theorizing: A Dialogue between Sinophone and Anglophone Scholarship on Relationalism.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 32, no. 5 (2019): 570–81.

Noureddin, Muhammed. “Turkey and the Arab Revolutions: ‘Composite’ Policies Putting an End to ‘the Strategic Depth.” Arab Affairs no. 146 (2011): 77–87. [in Arabic].

Ozkan, Behlül. “Turkey, Davutoglu and the Idea of Pan-Islamism.” Survival 56, no. 4 (2014): 119–40.

Ozkececi-Taner, Binnur. “Disintegration of the ‘Strategic Depth’ Doctrine and Turkey’s Troubles in the Middle East.” Contemporary Islam 11 (2017): 201–14.

Önhon, Ömer. Büyükelçinin gözünden Suriye [Syria through the Eyes of the Ambassador]. İstanbul: Remzi Kitabevi, 2021.

Öniş, Ziya. “Sharing Power: Turkey’s Democratization Challenge in the Age of the AKP Hegemony.” Insight Turkey 15, no. 2 (2013): 103–22.

Öniş, Ziya, and Şuhnaz Yilmaz. “Between Europeanization and Euro‐Asianism: Foreign Policy Activism in Turkey during the AKP Era.” Turkish Studies 10, no. 1 (2009): 7–24.

Park, Bill. “Turkey’s ‘New’ Foreign Policy: Newly Influential or Just Over-active?” Mediterranean Politics 19, no. 2 (2014): 161–64.

Pope, Hugh. “Pax Ottomana? The Mixed Success of Turkey’s New Foreign Policy.” Foreign Affairs 89, no. 6 (2010): 161–71.

Qin, Yaqing. “A Multiverse of Knowledge: Cultures and IR Theories.” Chinese Journal of International Politics 11, no. 4 (2018): 415–34.

–––. A Relational Theory of World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Saleh, Yasin Al-Haj. “The New Turkey is not a Revived Ottoman [State].” Journal of Palestine Studies no. 85 (2011): 149–57. [in Arabic]

Shaw, Stanford. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

Sözen, Ahmet. “A Paradigm Shift in Turkish Foreign Policy: Transition and Challenges.” Turkish Studies 11, no. 1 (2010):103–23.

Stein, Aaron. “I. Introduction: The Search for Strategic Depth-The AKP and the Middle East.” Whitehall Papers 83, no. 1 (2014): 1–10.

Taşpınar, Ömer. “Turkey’s Strategic Vision and Syria.” The Washington Quarterly 35, no. 3 (2012): 127–40.

Tayla, Alican. “Un nouveau paradigme pour la Turquie? [A New Paradigm for Turkey?]” Confluences Méditerranée no. 79 (2011): 57–65.

Tickner, Arlene B. “Core, Periphery and (Neo)Imperialist International Relations.” European Journal of International Relations 19, no. 3 (2013): 627–46.

–––. “Hearing Latin American Voices in International Relations Studies.” International Studies Perspectives 4, no. 4 (2003): 325–50.

Tickner, Arlene B., and Karen Smith, eds., International Relations from the Global South: Worlds of Difference. Oxon: Routledge, 2020.

Tuathail, Gearóid Ó, and John Agnew. “Geopolitics and Discourse: Practical Geopolitical Reasoning in American Foreign Policy.” Political Geography 11, no. 2 (1992):190–204.

Tuğtan, Mehmet Ali. “Kültürel değişkenlerin dış politikadaki yeri: İsmail Cem ve Ahmet Davutoğlu [The Place of Cultural Variables in Foreign Policy: İsmail Cem and Ahmet Davutoğlu].” Uluslararası İlişkiler 13, no. 49 (2016): 3–24.

Türkeş, Mustafa. “Decomposing Neo-Ottoman Hegemony.” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 18, no. 3 (2016): 191–216.

Waldman, Simon A., and Emre Caliskan, The ‘New Turkey’ and Its Discontents. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Walker, Joshua W. “Learning Strategic Depth: Implications of Turkey’s New Foreign Policy Doctrine.” Insight Turkey 9, no. 3 (2007): 32–47.

Yalçın, Hasan Basri. “Stratejik derinlik ve karmaşık nedensellik ağı [Strategic Depth and Complex Causality Network].” In Köse, Okumuş, and Duran, Stratejik zihniyet, 147–86.

Yalvaç, Faruk. “Strategic Depth or Hegemonic Depth? A Critical Realist Analysis of Turkey’s Position in the World System.” International Relations 26, no. 2 (2012): 165–80.

Yanık, Lerna K. “Constructing Turkish ‘Exceptionalism’: Discourses of Liminality and Hybridity in Post-Cold War Turkish Foreign Policy.” Political Geography 30, no. 2 (2011): 80–9.

Yavuz, M. Hakan. Nostalgia for the Empire: The Politics of Neo-Ottomanism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Yeşiltaş, Murat. “The Transformation of the Geopolitical Vision in Turkish Foreign Policy.” Turkish Studies 14, no. 4 (2013): 661–87.

–––. “Türkiye’yi stratejileştirmek: stratejik derinlik’te jeopolitik muhayyile [Strategizing Turkey: Geopolitical Imagination in Strategic Depth].” In Köse, Okumuş, and Duran, Stratejik zihniyet, 89–122.

Zambrano Márquez, Diego Miguel. “Decentering International Relations: The Continued Wisdom of Latin American Dependency.” International Studies Perspectives 21, no. 4 (2020): 403–23.

Zengin, Gürkan. Hoca: Türk dış politikasında ‘Davutoğlu etkisi’ [Professor: ‘Davutoğlu Effect’ in Turkish Foreign Policy] İstanbul: İnkılap Kitabevi, 2014.