Belgin San-Akca

Koç University

In this paper, I examine the generation and use of large-N datasets and issues related to operationalization and measurement in the quantitative study of inter-state and intra-state conflict. Specifically, I critically evaluate the work on transnational dimensions of internal conflict and talk about my own journey related to my research on interactions between states and nonstate armed groups. I address the gaps in existing research, the use of proxy measures in large-N data analysis, and talk in detail about observational data collection and coding. I argue that future research should bridge the gap between studies of conflict across the fields of Comparative Politics and International Relations. I make suggestions laying the standards of academic scholarship in collecting data and increasing transparency in research.

1.Introduction

August Comte, founder of the discipline of sociology, wrote about positivism back in the mid-19th century, claiming that there are laws governing human behavior and the social world similar to laws that govern natural phenomena. According to Comte, human behavior could have been explained and predicted through reason and observation. Nevertheless, it was not till after the end of WWII that discontent about the inability to predict the collapse of democracy in Germany during the inter-war period and the subsequent emergence of fascism resulted in research emphasizing the scientific pursuit of empirical facts and objective truth. It took positivism almost a century to influence the study of political phenomena. Its effect was mostly driven by the development of probability sampling techniques and the ability to conduct mass surveys, which facilitated the study of electoral choices. Positivism stresses collecting and recording data, which allows replication of social scientific research.

Positivism aspires to discover empirical regularities across human and societal behavior and builds on the assumption that social phenomena are like natural phenomena. Social scientists should focus on observable phenomena, which constitute the basis for quantifiable data. In the view of positivists, “facts exist independently of the observer and his or her values”.[1] The purpose of social scientists, then, is to accumulate an objective pool of knowledge, which can be used to explain and predict causality across a complex set of concepts and events. Both social and natural sciences are united in terms of deducing testable hypotheses from new ideas and pre-existing theories and comparing them to observed individual experiences for verification.[2] This approach to scientific discovery denies non-testable theories. Empirical scientists do not have any interest in such metaphysical explanations, which do not require observation of individual behavior for generalization and prediction.

This positivist approach has been driving the development of Political Science as a discipline across Europe and North America from the 1930s on. Due to its emphasis on the observation of individual human behavior to verify hypotheses and predict future behavior, it is referred to as behavioralism in Political Science. Initially being puzzled by the inability to predict the rise of fascism in Germany during the inter-war period, early research using the behavioral approach focused on explaining and predicting people’s electoral choices.[3] Behavioralists criticized the early work related to political phenomena, which relied on qualitative and normative research to describe how individuals comply with formal rules and institutions. They, on the other hand, emphasized explaining how individuals behave and make decisions in various social settings.[4] Their reliance on quantifiable and empirical data made behavioralist scholars study human behavior as it is rather than as it ought to be. In this respect, the purpose of political scientific research was not about introducing values and ethical standards. The goal of political scientists was to produce value-free empirical and objective knowledge about social regularities. Therefore, sampling, interviewing, scoring and scaling, and statistical analysis were the main instruments of research in the 1960s and 1970s.

The impact of behavioralism was not limited to the study of electoral choices. Its arrival into the field of war and conflict happened in the same period.[5] The behavioral study of war acknowledged it as undesirable from early on.[6] Yet, to be entirely abolished from the human agenda, war must be understood fully. Much of this early research agenda, which encompassed both a normative view of war as undesirable and a desire to achieve an extensive definition of war, was referred to as peace research. War was being quantified and studied to achieve peace in the world.[7] Two major quantitative studies of war were developed in this context: the Correlates of War (COW)[8] and the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP).[9]

Since the end of WWII, over 20 million people (around 3.5 million as battle-related deaths and the remaining 16.5 million as civilians) have died in internal conflicts or civil wars within the borders of states, while around 2 million people have lost their lives during wars between or among states.[10] Among many factors that have contributed to the unprecedented amount of fatalities during internal conflicts, the most striking ones are the change in the nature of insurgencies—they tend to have increasingly deadly technology,[11] and the endurance of armed groups that instigate violent campaigns against their governments..[12] According to the Dangerous Companions Project, among 454 nonstate armed groups that fought against governments in the post-1945 period, almost 60% received some form of military, material, and logistics support from outside states.[13] This means that foreign state support is a significant factor contributing to the endurance of nonstate armed groups as well as increasing duration of conflicts.

It has been almost seventy years since President Truman gave his seminal speech later characterized as the “Truman Doctrine.” The distinction between civil war and international war was meaningless, according to Truman, even if there was a slim chance that civil war would lead to communist insurgent victory and the establishment of communist regimes. In Truman’s view, the U.S. had to fight against “changes in the status quo… by such methods as coercion, or by such subterfuges as political infiltration”.[14] The subsequent years witnessed active U.S. involvement all over the world, to avoid regime change through communist insurgencies by providing military and financial aid to governments fighting against insurgents.

Clearly, external state intervention in internal conflicts was neither under the monopoly of the U.S., nor was it directed against insurgents in every instance. In contrast, frequently, states found themselves providing some form of support to dissidents, rather than governments fighting against domestic dissidents. Nevertheless, most theories and empirical studies of civil war, rebellion, and insurgency focused on domestic political, social and economic conditions in explaining conflict onset. Scholars of international conflict, on the other hand, have ignored nonstate armed actors, privileging states as the major actors shaping world politics.

In the past couple of decades, two major developments have signaled that scholarly thinking about domestic and international conflict should be reinvigorated: 1. there is a reduction of direct inter-state war over time, probably more so in the post-WWII period, and 2. civil wars or ethnic conflicts turn out to be the prevalent form of violence in the post-Cold War period. Furthermore, civil wars tend to last longer and spread across the borders of neighboring states, thus easily transforming into transnational conflicts. These developments require us to think about conflict in a broader sense regardless of its domain to unwrap the causal mechanisms through which interstate relations influence internal conflict dynamics. Only a unified theoretical framework looking at internal conflict through the lenses of interstate conflict and cooperation patterns can provide novel insights for broad questions about why nonstate groups prefer violence over nonviolence and why certain states prefer nonstate armed groups as partners rather than states.

With these in mind, I continue with a sketch of major scholarly works on civil war and explain how I positioned my own research along the lines of foreign state support of nonstate armed groups to bridge the gap in the study of conflict across both domestic and international domains. The following section talks about the Dangerous Companions Project and data collection and coding processes related to this project. The final section makes some recommendations about the development of some theoretical frameworks linking the apparently distinct realms of domestic and international conflict.

2. Time-Series Cross-Sectional Data and the Study of Conflict

The dominant approach to the study of conflict and cooperation in inter-state relations in the post-Cold War period has, till recently, focused on democratic states’ potential to engage in peaceful international relations. Most research about democratic peace produced findings using two major datasets: the Polity Dataset[15] and the Correlates of War Project War Dataset (COW).[16] From the analysis of these datasets, there emerged a scholarly consensus on the negative impact of democracy on inter-state war, although such consensus is missing when it comes to the factors that drive the onset of internal or domestic conflict, such as ethnic rebellion and civil war. The intuitive anticipation related to the role of democracy or democratic institutions in internal conflict is that democratic institutions help mediating conflict among distinct segments of a society. Therefore, democracies should be less likely to experience civil war or internal conflict. Yet, existing research produced mixed results with respect to the effect of regime type on the likelihood of civil war onset.[17] This body of research relied mostly on the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset[18] and the COW civil war data.[19]

Even though a large-N analytical approach was adopted by a significant number of scholars studying conflict across both domains of domestic and international politics, for a long while there has been an intellectual division within conflict studies. This intellectual divide can partly be attributed to the high risk contained in studying conflict under a unified theoretical framework. It is more convenient to study signs of conflict, such as war, terrorism, revolution, and ethnic strife to avoid criticism associated with a holistic approach. The ongoing conflict in Syria, and the intervention by multiple outside states and nonstate actors demonstrate, once again, that internal conflicts are rarely confined to the domestic setting in which they occur. Therefore, we are in need of urgent scholarship that can yield a clear understanding of the intricate dynamics of interactions not only among states, but also between states and non-state armed groups.

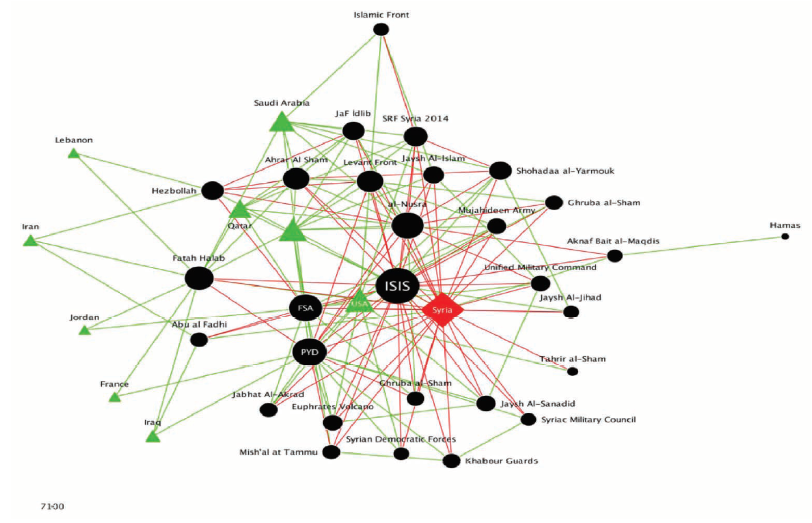

Figure 1 displays all actors that were involved in the Syrian conflict in 2015. The green lines indicate the alliance or support ties between outside states and nonstate armed groups as well as among groups and among states. The red lines show the enmity ties similarly. The black circles show the nonstate armed groups’ centrality, i.e. the number of alliance and enmity ties they have with external states and other nonstate armed groups. The green triangles refer to the countries, and their size indicates the number of alliance and enmity ties they share with groups.

Figure 1: Syria, 2015

The Syrian conflict is neither the first nor the only one with so many actors involved. During the Cold War period, external intervention in internal conflicts or support of one of the disputants was shaped primarily by the strategic interests of nation-states—mostly regional or major powers. This has not changed. Indeed, supporting domestic dissidents has evolved into a normal foreign policy practice given that states have increasingly become more reluctant to confront each other by waging direct wars. Whether to achieve domestic regime change, liberate the minorities living under repressive regimes, put an end to atrocities seen in civil wars, or gain leverage over an enemy, states have been motivated to intervene in each other’s internal conflicts either through supporting the government or the opposition side. The type of intervention varies from overt to covert as well as from military to economic and diplomatic support to either side in a conflict, i.e. the government and/or nonstate armed groups.

Foreign state intervention in internal conflict has been serving as a major means through which internal conflicts are internationalized. A considerable amount of work has emphasized the role of outside state support on the onset, evolution and termination of internal conflicts although the role of outside state support on conflict onset is still understudied. We know that outside intervention prolongs civil wars; states are more likely to interfere in internal conflict of others if there is transnational ethnic kin; and states support armed groups due to both strategic and ideational motives.[20]

While the end of the Cold War signaled an end to super power rivalry, as mentioned earlier, the international realm has been plagued with violence emanating from the actions of various types of non-state armed groups; i.e. ethnic and/or religious insurgents, terrorists, and militants. The more intriguing phenomenon has been the ability of these groups to adapt quickly to this new environment, which no longer had the super power patrons conveniently providing resources to them. How do armed groups attract support within the borders of other states? Why do states support rebel groups despite the fact that it might attract retaliation? Why and how did supporting armed groups transform into a foreign policy strategy frequently adopted by states? What are the implications of this transformation for interstate conflict and cooperation?

To answer these questions, I developed the Dangerous Companions Project (nonstatearmedgroups.ku.edu.tr). The project’s output is twofold. On the one hand, it presents a unique cross-sectional time-variant dataset on ideational characteristics, objectives and foreign state supporters of armed groups that have been active in the post-WWII period. It also has information on several types of outside state support, i.e. safe havens, training camps, open offices, funds, and weapons. On the other hand, it includes bibliographic information about the sources used for coding each group included in the dataset. The project’s website, therefore, serves as a reference for the main sources to be utilized for quick information on each rebel group.

I conceptualized the interactions between states and armed groups into two types: 1. governments intentionally provide support to certain groups, and 2. armed groups select certain states to obtain resources from. This second type of interaction is essential for capturing long-term shifts in armed groups’ ability to learn how to acquire resources abroad. This was necessary to cover the cases in which armed groups were not intentionally supported by a given government, but were still able to operate within the borders of a country under that government’s jurisprudence. This approach makes it possible to test some hypotheses that were put forward related to the effect of the end of the Cold War on intervention in civil war. Though the super power rivalry’s termination meant that armed groups would not find the resources they needed readily available, they managed to adapt to the changing interstate environment over time. Therefore, it is essential to trace the causes of foreign state support for rebel groups to the inter-state relations.

2.1. Why collect large-N data?

An analysis of long-term patterns in the interactions of states and armed groups requires going beyond simple case study analysis limited to exploring the mechanisms with a small number of cases. Although case study analysis is significant for uncovering the causal mechanisms at play, it does not allow us to capture broader linkages between inter-state relations and increasing state-rebel group alliances. Initially, I examined three cases: (1) Iran during the Shah period when it enjoyed the support of a very strong ally, the USA, against a very strong Soviet threat; (2) Lebanon during the 1960s wherein there was not much threat facing Lebanon in the first half of the decade, but then the 1967-68 war changed the Lebanese external security environment; and (3) Syria during the 1990s, when it was abandoned by the Arab world in international politics and domestic leadership had a lot of pressures from bureaucrats and public in general to move forward with liberal economic reforms.

The objective of the case study analysis was to develop a grounded theory about the possible mechanisms through which some states choose to support armed groups against some other states. I chose the countries on the basis of three criteria: countries that are engaged in protracted conflicts make it easy to identify perceived adversaries, which are asymmetrically powerful and to control for the degree of threat across cases. Second, I examined countries that vary in their ability of internal mobilization – ability to extract for arms buildup. The third criterion for case selection was to identify countries with various sets of response strategies. My purpose was to determine the variation in ability to achieve internal mobilization and specify a list of potential responses against external threats. These cases were studied for a paper, which was written as part of the requirements of a graduate seminar on qualitative methods.

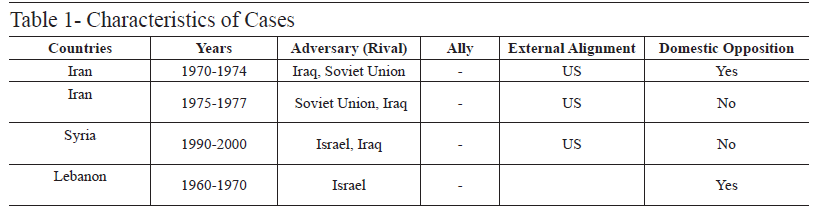

The table below describes the characteristics of the cases. Every case was part of an enduring rivalry during the relevant period. Therefore, we can argue that there was a high external threat environment during the period. All of the four cases faced an asymmetrically powerful adversary with the exception of Iran between 1970 and 1974. Iran’s catching parity with Iraq was not impossible during that period, yet Iraq had signed an alliance agreement with the Soviet Union in 1972, which led to extensive Soviet export of weapons to the Ba’th regime in Iraq[21]. Therefore, in the first half of the 1970s, it is possible to argue that Iran was facing an asymmetrically powerful rival that was backed by the Soviets. In addition, the Soviet threat was always present for the Shah regime. Furthermore, the Shah regime in Iran faced domestic opposition throughout the 1970s, which resulted in increasing expenditures on arms importation from the United States. There was not an alliance agreement signed between the Shah regime and the United States, but Iran was aligned with the US during the 1970s and the Shah himself was placed in power as a result of a US-backed coup d'état.

The first phase of data included around 125 armed groups, which were active between 1946 and 2001. It was funded by a Dissertation Improvement Grant by the Institute of Governmental Affairs, University of California in 2008. Later, after the completion of my doctoral studies,the broader project including around 450 armed groups was funded by a Marie Curie Reintegration Grant for a four-year period between 2011 and 2015. Throughout the period, during which data collection was completed, several undergraduate and graduate students were trained and employed as coders.[22] The output of the overall project was published in a book by Oxford University Press in 2016.[23]I distinguished between an alliance and alignment. Alignment does not mean a formal agreement among partners that entails helping each other in case of an external attack. Alignment points to sharing similar ideological, strategic, and foreign policy objectives to some extent. In this sense, although Iraq and Syria had close relations during the 1960s and 1970s, it does not mean that the two regimes were allies. After a detailed review of these cases, I developed a coding protocol for defining cooperation between states and armed groups as well as starting to build up a grounded theory to guide the data collection effort.

3. Examining Internal Conflict through the Lens of Interstate Relations

In the post-WWII period, a total of 104 states had to fight against armed groups challenging them for some territorial and/or governmental concessions. Seventy-eight of these states had to fight armed groups, which were supported by foreign states. This corresponds to 75% of all conflict-ridden states. Out of 454 armed groups, that were active in the same period, 234 were supported by foreign states. This means that almost 52% of armed rebel groups were supported by outside states seeking to somehow influence the course of a given internal conflict. A total of 62% of all internal conflicts involved outside interveners in the same period.[24]

The study of internal conflict or domestic contestation has been spread across multiple fields. Since Gurr wrote the famous “Why Men Rebel”, scholarly research has identified individual grievances as the major source of domestic conflict, such as rebellions, ethnic strife and civil war.[25] Indeed, most empirical research assumes individual grievances are automatically aggregated at the group level to give birth to internal conflict. Once violence is experienced, ethnic strife or civil war is the outcome of the frustration leading to the collective expression of the individual grievances. However, the theory of relative deprivation and explanations at the frustration-aggression nexus inadequately clarified how violence was born out of anger. Neither did they explain the conditions under which violence was perceived as a logical instrument to pursue grievances.

To fill this gap, utility-based or rational-actor approaches were adopted. In their prominent work on whether greed, as an indication of utility-driven violence, or grievances leads to civil war, Collier and Hoeffler challenged the conventional wisdom.[26] In line with these approaches, two strands of research have been dominating the study of internal conflict. Frequently applied to the study of ethnic strife, the major source of mobilization for ethnic groups is attributed to the discrimination policies pursued by the majority ethnic group in the domestic realm. On the other hand, those who favor the rational actor approach, argue that individuals occasionally behave to maximize their benefits rather than address their grievances, though it is not difficult to see how the two, utility maximization and addressing grievances, could complement each other or overlap.

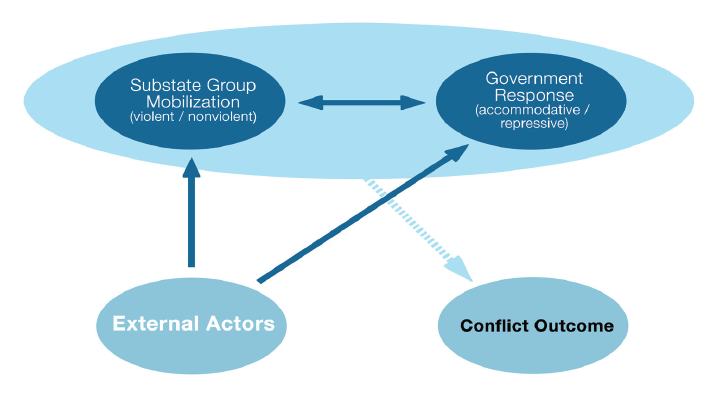

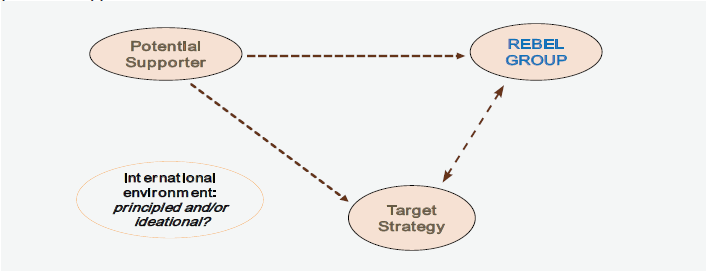

What is missing in this overall picture is the role international norms, regulations, and external actors play in convincing a dissatisfied group of individuals that it is conceivable and logical to organize and press for specific claims from political authorities to address the collectively felt grievances. Furthermore, external actors might signal to dissidents whether the use of a specific type of instrument for the expression of grievances is acceptable or not. In other words, the international community can play an effective role at this mobilization stage, when individual grievances are translated into collective action by:

Figure 2 provides a visual description of the theoretical framework disaggregated by the actors. My future goal is to develop interdisciplinary and systematic explanations of domestic conflict dynamics as a function of the macro-historical changes in the international system to test hypotheses about the following propositions:

Figure 2: Visualizing the Linkages between Domestic Conflict Dynamics and External Actors

Why do we need such an overarching framework? As mentioned previously, though we have invaluable research on transnational dimensions of civil war, we still lack a consistent and systematic joint scholarly effort to explain the role outside states play in conflict onset and the responses of target governments to rebel groups when there are outside states involved. Nor do we have such scholarship on how foreign state support influences the strategy and objectives of armed rebel groups. In other words, we need to more effectively bring interstate relations into the study of civil war. To do that, we need nuanced data disaggregating the nature of interactions between states and rebel groups.

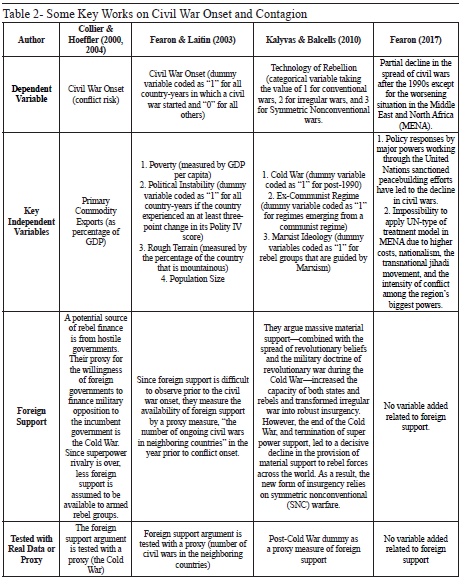

The causes of civil war or internal conflict seem to be investigated in the limited domain of domestic politics. Key works identify political grievances, economic inequality, and greed-related motives as the major source of internal conflict though there is no consensus on what drives deprived groups to rebel and resort to violence. When they try to bring in foreign state support as an explanation, usually it is treated as a control variable rather than a key explanatory variable. Therefore, most empirical research, till recently, used proxy measurements or variables to capture the effect of this significant control variable.[27] Table 2 presents the empirical framework of four key published works on internal conflict onset and identifies the gaps in knowledge and empirical designs.

The most significant puzzle that inspires the civil war literature is the lack of relationship between ethnic-religious diversity of a country and its predisposition to civil conflict. Scholars intrigued by this puzzle developed systematic explanations for the conditions under which such countries experience conflict. Fearon and Laitin[28] argue that the key determinants of civil war are poverty, political instability, rough terrain and population size. Building on the opportunity explanation of Collier and Hoeffler,[29] they argue that access to resources motivates rebellion only if political institutions fail to translate grievances into policy. While Collier and Hoeffler argue that rebellion is a function of the perceived opportunity to loot resources by rebels, Fearon and Laitin argue that resources motivate rebellion if there is economic inequality to begin with and the state has a weak capacity to govern. Further, they argue that resource-rich states are more likely to end up with weak state institutions since they use such resources to buy the support of domestic public rather than spend them to strengthen their military capacity.

The financially, bureaucratically, and militarily weak states, due to poverty, present rebels with more opportunities to recruit militants and loot resources. According to Fearon and Laitin[30], the evidence shows that poverty increases the likelihood of civil war outbreak. When poverty-related measures (GDP per capita) are controlled for, ethnic and religious diversity or fractionalization are not significant factors to determine whether civil war will be experienced or not. Furthermore, political instability increases rebels’ chances to organize and seek rebellion, thus increasing the likelihood of civil war onset.

When it comes to foreign state support, Fearon and Laitin talk a great deal about foreign support and how it can encourage rebellion and insurgency. Yet they do not test this proposition empirically. The additional empirical tests, not published in the article, include the number of ongoing civil wars in one’s neighborhood, yet they do not yield any significant results. [31] This is surprising given that among the 110 civil war onset cases identified by Fearon and Laitin in the period between 1945 and 1999, 70 were identified to have a foreign state supporter.[32] The challenge remains, though. We do not know if there was any role played by foreign states in instigating violent rebellion before conflict initiates.

Kalyvas and Balcells pointed to the changing technology of rebellion across the Cold War and post-Cold War periods. They demonstrate that, with the end of the Cold War, a significant change occurred in the international system which affected both states’ and rebels’ capacity: the decrease of support from the two superpowers. The change in their capacity affected the way rebels fight. They list three technologies or styles of rebellion. First is conventional civil war, which emerges when the military technologies of states and rebels match. Irregular civil war emerges when the military technologies of the rebels lag behind those of states. And, symmetric nonconventional (SNC) warfare emerges when the military capacity of the state and rebels match at a low level. This latter form is mostly the case when a state lacks capacity.

Their theory about the changing nature of insurgent technology relies on the assumption that material support was in decline in the post-Cold War period in comparison to the Cold War period due to the decline in super powe support. Yet the NAGs Dataset shows that while around 62% of the total years in which there was some type of support to rebel groups, belongs to the Cold War years, the remaining occurred in the post-Cold War era. A comparison of the number of groups that received foreign state support across the two periods reveals that while 49% of all armed groups active during the Cold War period received such support, 53% of groups received such support in the post-Cold War era.[33] If there was a change in the technology of rebellion, it was not due to the decline of foreign state support. One needs to examine the change in the ideology, objectives and nature of such groups to explain the change in the technology of rebellion.

4. The Collection of Data on Relations between States and Nonstate Armed Groups

Scholarly explanation about how the causal mechanism works from foreign support to civil war, has included investigations on the effect of transnational ethnic kin, safe havens across borders, and interstate rivalry.[34] When it comes to the effect of outside intervention on conflict duration and termination, the main explanations focus on whether there are multiple third parties intervening, the interaction among them, on whose side they intervene, and their motivation for intervention. Regan takes the lead in pointing out that it matters if the intervention is biased toward either side of an internal conflict or remains neutral, while Aydin and Regan refine this argument by examining the nature of relations between states intervening in the same conflict.[35] Their finding is similar to that of Balch-Lindsay and Enterline, who conclude that balanced interventions prolong civil wars.[36] Aydin and Regan find that in the case of multiple interveners, intervention on the same side by these interveners can shorten civil wars if they also share similar interests. Thus, this finding goes beyond simply stating that intervention on one side shortens civil wars.

By the same token, Cunningham argues that it is not about whether an intervention is on one side of an internal conflict, but about the intentions of the interveners.[37] Those who have their own agenda prolong civil wars rather than shorten them. Some recent work renews the debate about whether outside interveners influence civil war duration through provision of funds, weapons, and safe havens. Wood examines the effect of foreign support on civilian targeting during civil war while Sawyer, et al. find that states fight rebels longer if rebels receive fungible external resources.[38]

Other bodies of research one can draw on are placed in the study of proxy warfare and promotion of regime change by outside actors.[39] Most of this research focuses on a specific type of intervention, namely overt military intervention, and does not disaggregate the actors involved. This last issue is also present in the extensive literature on external intervention, though less so in the research specifically focusing on external state support of nonstate armed groups.

Especially when there is more than one armed group fighting against a state, it is essential to examine each group and its ties with outside actors to build nuanced explanations about why states prefer supporting one group over the other. While the US and Turkey are both allies of NATO, the US provides arms and funds to the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and People’s Defense Units (YPG) in Syria, which are both considered to be terrorist organizations by Turkey. By the same token, while Russia and the US agree on the fight against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), they disagree on whether to take sides with the Syrian government and Assad regime. Indeed, the US wants regime change, while Russia wants to maintain the rule of the current Syrian regime. These complex interactions can only be captured if we disaggregate internal conflicts to multiple stages and actors involved.

4.1. Conceptualization of foreign state support

Foreign state support takes several forms, such as arms, funds, safe havens, and military equipment. Since such support to armed groups goes usually secret, it is not always easy to find this information. Furthermore, governments might or might not allow rebel groups to operate freely in their borders. The overwhelming belief in the post-Cold War period was that armed groups exploit the weak states, which are unable to control their borders. Yet we know that it is the modus operandi for states to support such groups to achieve foreign policy objectives. Among the 454 groups for which foreign state support was coded in the NAGs Dataset, 203 groups were able to move freely within the borders of many states and raise resources. One hundred fourteen states turned out to be either safe havens for group militants seeking refuge in foreign territories, financial hubs for raising money, or weapons smuggling and transportation points.

I treat states and armed groups as equivalent actors in world politics. When armed groups are offered some support from states, they decide whether or not to accept such support. When armed groups make such decisions, they are mostly concerned with the autonomy of their operations. Since a foreign government aiding or abetting an armed group does not want to lose control over its protégé, groups would carefully choose their state allies to maximize their autonomy of conduct.

To fully capture the complex web of interactions between states and armed groups, I developed a selection model of states and groups. I argue that armed groups, as well as states, choose their allies carefully. State selection occurs when the government of a given state creates channels to support an armed group intentionally. Rebel selection occurs when a rebel group seeks support within the borders of a state without the government or politicians of that state intentionally creating such channels. Rebel selection cases are usually specific to democratic states, which have institutions embedded with liberal norms. The democratic freedoms and liberties built into democratic systems are exploited by armed groups, which are in constant search for resources.[40]

The following example is related to the M-19 Group of Colombia and helps further explain the coding process and the kind of information we looked for when coding foreign state support for armed groups.

State Selection Case of Support: Below is an example of an excerpt that is used from published news resources and media to collect and code information about the M-19 group of Colombia:

In related developments, a former M-19 member claimed the group receives ''suitcases of dollars'' from Cuba and training from Nicaragua.

In an interview with the Cali newspaper Occidente Flor Marina said, ''The M-19 has Cuban, Libyan, Nicaraguan and Peruvian trainers in the mountains.''

''Suitcases of dollars arrive from the outside, especially from Cuba, and are changed in Bogota,'' she said. ''Arms arrive continually from Cuba, Nicaragua, Libya and El Salvador.''

The woman said she escaped from the rebel group after five months. She said she was tricked into joining the group when a friend invited her on a trip to visit his parents.[41]

One of the four Libyan cargo planes detained in Brazil

enroute to Nicaragua was carrying weapons for Colombia's largest guerrilla

group, Colombian Defence Minister Fernando Landazabal said yesterday.He told reporters the country's security services learned that a U.S.-

built Hercules C-130 was carrying arms for the M-19 group, but the plan

was foiled when a technical fault forced it to land in Manaos, Brazil.

'We were ready to repel the operation,' General Landazabal said. He

added the army had knowledge that the M-19 guerrillas were due to receive

weapons either from Libya or Europe.…The reports said that the arms shipment was planned to coincide with

the 13th anniversary of the creation of the M-19, best known for the two-

month seizure of the Dominican Embassy in Bogota three years ago.The M-19 broke an undeclared truce, military sources said, by launching

a dawn attack on Puerto Asis two days ago in which five guerrillas were

killed. There were no casualties among security forces, the sources said.The newspaper El Tiempo reported on Thursday that M-19's leader, Jaime

Bateman, was recently in Libya, where he met Libyan leader Muammar

Gadaffi. Mr. Bateman told reporters three days ago that he will resume a

kidnap campaign to finance the M-19's activities and has ordered his

guerrillas back into hiding.…Gen. Landazabal told Radio Caracol that each of the four planes was

carrying 42 guerrillas.

"We are carrying out private investigations to establish if any M-19

guerrillas were included among them," he said.[42]

These news reports provide credible information about possible channels through which M-19 raises resources. When confirming a specific piece of information, the coding protocol required coders to verify the information from at least three different sources.

De Facto Rebel Selection Case of Support: The following is an example of a news report used for coding de facto support, which occurs without the consent of the government of a state within which a group is able to recruit, establish safe havens, and raise funds. The news include information about Free Aceh Movement (GAM)’s use of Thai and Malaysian territories for weapons smuggling and safe haven. Since Thai and Malaysian governments cooperate to catch the smuggled weapons and GAM militants, Thailand and Malaysia are coded as de facto supporters of GAM.

…Thai police are on the lookout for a Free

Aceh Movement (Gerakan Aceh Merdeka or GAM) arms-smuggling syndicate

mastermind who operates on both sides of the Thai-Malaysia border.They also seek the co-operation of Malaysian police to find and detain

the suspect, an Indonesian citizen.This follows the discovery that recent seizures of high-powered arms in

this coastal district situated north of the border from Perlis, was headed

for Aceh, north Sumatra.This year alone, Thai police here have seized four M-79 grenade

launchers, 17 grenades and 36 automatic assault rifles consisting of M-16s

and AK-47s, all headed for the war-torn Indonesian province.Satun police chief Major-General Prajak Musikasukont said the mastermind

sourced the weapons from Cambodia and was using Satun as a transit point."The syndicate has been operating for four years and the mastermind is

always commuting to and fro between southern Thailand and several areas in

Malaysia, including Langkawi, in an effort to evade capture," he said at

the Satun district police headquarters today…[43]

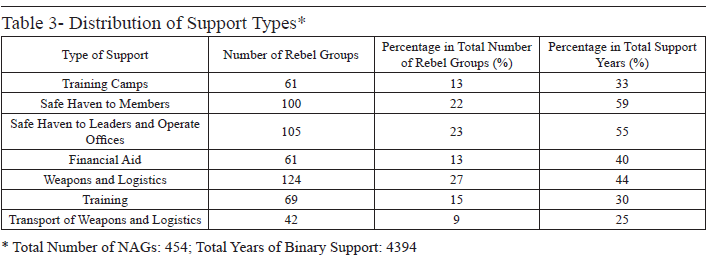

Since a state might turn out to be both an intentional and de facto supporter, it is possible to code the same state for both and specific types of support. Below is a distribution of types of support coded. The first column gives figures in terms of the number of NAGs receiving each form of support. The second column introduces the figures related to each category with respect to the proportion of number of NAGs receiving a specific form of support to the total number of NAGs coded (454). The last column provides the percentage of each type of support to the entire years of support. Since the unit of analysis is triadic, it makes sense to think about it in terms of total number of binary support years.

4.2. Unit of analysis: a triadic analysis of support onset

The theoretical framework I developed proposes an analysis of support onset through the lens of interstate relations. Therefore, I constructed a triadic time-series cross-sectional dataset to capture the effect over time as well as across different cases. A case emerges as soon as a NAG starts to challenge a state for the following objectives: 1- toppling an existing leadership, 2- change of regime type (transition from autocracy to democracy or the reverse regime change), 3- demands for autonomy, 4- secession/territorial demand, and 5- demands for policy change. The state, which is the subject of the NAG’s attack is called the “target”. Ideally, all other states in the world are potential supporters. When coding state support, I treated each state as such. Yet when conducting the empirical analysis in some of my publications, I narrowed down the list of potential supporters for every NAG. This was necessary to handle an unnecessary inflation of zero observations. Figure 3 presents a visualization of the anticipated interactions among a NAG, its target and a state, which I call a “potential supporter”. Support onset is explained through the developments in the interstate environment of targets and potential supporters as well as the interactions between target and potential supporter.

Figure 3: Potential Supporter-NAG-Target State Triad

Potential Supporter: A state is called a potential supporter of a NAG, if it is in the Politically Relevant Group (PRG) of a target state. Most dyadic states of interstate war also adopt a similar strategy. It would not be theoretically intuitive to anticipate a militarized dispute between Somalia and Sweden since they are located so distant from each other. The PRG of a state includes geographically contiguous states, regional powers and major powers. Regional and major powers are included among potential supporters of each NAG since they have some aspirations that stretch over a broader geographical area.[44]

A NAG-target state dyad is then paired with each state in the PRG of a target state for empirical analysis. Using the NAGs dataset, it is possible to identify which of the states in a PRG transformed from potential supporter to actual supporter. Each triad is listed for the entire period during which a NAG survived.

4.3. Data sources, credibility and transparency

The Dangerous Companions Project has a website, on which sources used to code information about foreign state support are publicly shared under the profile of each NAG. This is especially significant to increase transparency in academic research and make information available to public.

Furthermore, to give users a sense of credibility and precision of the information found, a precision variable is coded for each foreign state supporter and each type of support. In order to specify how confident the coder is about the evidence of active support, the variable receives the following scores. Lower scores correspond to higher level of precision, thus higher level of credibility:

1 – The supporter outright stated its intention and/or type of support, and/or the support was officially documented by that state or another.

2 – A reliable journalist, scholar, or media outlet recorded the support and provides convincing evidence and there are other sources that confirm this information.

3 – Support is highly suspected by a reliable source (such as journalist, scholar, or media outlet), but cannot be confirmed by other sources.

4 -- One state accuses another state of supporting a group, but it cannot provide official documentation beyond allegations.

The information is mostly found using the following sources: Lexis-Nexis academic web program, Keesing’s Archives, and published secondary sources, including political science journals, journals focusing on particular regions of the world, books and book chapters. Each coder received training and was given a sample NAG to code to. Afterwards, inter-coder reliability was confirmed. Each coder was given a questionnaire with directions and guidance about how to conduct research on online databases and sources to find and collect the required data. The following keywords were searched in the Lexis-Nexis categories “Major U.S. and World Publications,” “News Wire Services,” and “TV and Radio Broadcast Transcripts” with each group’s name: support, assistance, sponsor, safe haven, sanctuary, training camps, camps arms, weapons, funds, and troops. [45]

The NAGs dataset is unique in terms of the temporal and spatial domain covered as well as the de facto support coding. Several other existing datasets coded third-party interventions in internal conflicts. Cunningham, Gleditsch and Salehyan’s Non-State Actor (NSA)[46], is a dyadic dataset that includes information for each NSA’s military strength and capacity, leadership characteristic, popular support and political linkages as well as external sponsorship. Nevertheless, external state support is not disaggregated. For any kind of support, it is coded as “1”. It also lacks the temporal dimension.

By the same token, UCDP External Support Data codes external supporters that give support to an armed group in a given year for the period between 1975 and 2010. It also codes for different types of support and the type of the external supporter.[47] These data, however, do not go beyond 1975 and are not time-variant. The total number of observations in the external support dataset is around 7,900, whereas the total number of observations in the NAGs Dataset is around 16,000. Furthermore, the NAGs dataset has time-variant information on both objectives and ideational characteristics of groups. If a group shifts its ideology from socialism to liberalism, this is a significant piece of information. Such nuanced data can provide an opportunity to observe how armed groups adopt new globally dominant ideologies from time to time to improve their ability to find foreign supporters. Finally, the literature on outside intervention in internal conflict yielded some data on foreign support of armed groups.[48] Yet they did not disaggregate the actors involved in the same intrastate conflict. It is important to know if country A supports group X, but does not do so for group Y, which are involved in the same conflict fighting against the same state.

5. Data Analysis

The empirical method that I used in the analysis related to the factors determining support onset for rebel groups relied on binary logit analysis with control over temporal dependence. The conventional method of controlling for temporal dependence is the method developed by Beck, Katz, and Tucker.[49] This method generates a variable that counts consecutive years or duration of non-cases. In this particular context, it would mean the consecutive years of no support observations. The idea is to account for time dependence. Given that a state provides support to a NAG in year X, it is more likely to continue its support in year X+1. There is a new method to control for temporal dependence developed by Carter and Signorino.[50] The main difference is that the previous method had cubic splines to capture the main spikes in temporal domain, whose their interpretation was difficult. Regardless, temporal domain has to be controlled for in the analysis of a dataset that contains time-variant information. Empirical analysis in some of my work was also conducted using this new method, yet there was not a significant difference between them and the method, which relies on cubic splines.

6. Conclusion and Future Research

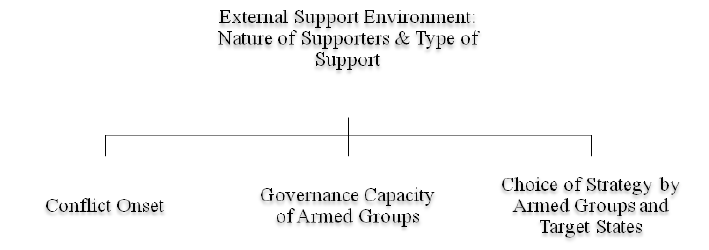

The NAGs dataset is prepared to facilitate further research on the effect of outside states on instigating rebellion and violent conflict within the borders of states. Given that we did not yet collect data to see if outside states somehow foster violent internal conflict, future scholarship might think about theoretical and empirical ways of addressing this question. We have extensive research about the transnational dynamics of internal conflict. Why do states intervene in the conflicts of others? How do they choose their side: government vs. armed group? Figure 4 demonstrates potential gaps in the existing research. We are yet to conduct research about the role of external state support on the choice of strategy by conflicting sides as well as the governance capacity of armed groups.

Figure 4: Future Research Venues

The challenge stems from the difficulty of identifying groups with potential grievances across every state. Most datasets on armed conflict, and the NAGs dataset is not an exception, are biased towards violence. This means that scholarship cannot empirically offer much when it comes to explaining how external states might fuel grievances within a state. Furthermore, the NAGs dataset relies on observational data rather than witness accounts. It uses interviews conducted by reliable news agencies to get primary information about state supporters of armed groups and case study analysis by scholars, yet it still falls short in incorporating a multiplicity of resources. It relies on Western media sources to a great extent, which is problematic at times.

This paper presented a personal history about a scholarly journey spreading across almost a decade. The dataset, which was the outcome of the mentioned project is now extensively used by scholars in Europe and North America. The empirical findings have yielded three articles and a book,[51] and are evidence of the power of using empirical data in a systematic manner. IR scholars in Turkey should adopt the highest standards when it comes to conducting academic research. Mere story-telling or future-guessing do not qualify as scholarly prediction, which must build on expertise in a specific area and empirical data.

Aydin, Aysegul, and P. M. Regan. “Networks of Third–party Interveners and Civil War Duration.” European Journal of International Relations 18, no. 3 (2011): 573–97.

Bakke, Kristin M. “Copying and Learning From Outsiders? Assessing Diffusion from Transnational Insurgents in the Chechen Wars.” In Transnational Dynamics of Civil War, edited by J. Y. Checkel, 31–62. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Balch–Lindsay, Dylan, and A. J. Enterline. “Killing Time: The World Politics of Civil War Duration, 1820–1992.” International Studies Quarterly 44, no. 4 (2000): 615–42.

Barnett, R. “Guerillas Convene 'Peace Conference'.” United Press International, Bogota, Colombia, 1985.

Barnett, Richard J. Intervention and Revolution: America’s Confrontation with Insurgent Movements around the World. Ontario: New American Library, 1968.

Beck, Nathaniel, J. N. Katz, and R. Tucker. “Taking Time Seriously.” American Journal of Political Science 42, no. 4 (1998): 1260–88.

Bouthoul, Gaston. War. New York: Walker, 1963.

Bouthoul, Gaston, R. Carrère, and G. Köhler. “A List of the 366 Major Armed Conflicts of the Period 1740–1974.” Peace Research 10, no. 3 (1978): 83–108.

Boyd, Gerald M. “Reagan Accuses Soviet of Aiding Latin Terrorists.” The New York Times, January 3, 1986.

Burnham, Peter, K. G. Lutz, and W. Grant. Research Methods in Political Science. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Carment, David, P. James, and Z. Taydas. “The Internationalization of Ethnic Conflict: State, Society, and Synthesis.” International Studies Review 11, no. 1 (2009): 63–86.

Carter, David B., and C. S. Signorino. “Back to the Future: Modeling Time Dependence in Binary Data.” Political Analysis 18, no. 3 (2010): 271–92.

Cederman, Lars-Erik, L. Girardin, and K. S. Gleditsch. “Ethnonationalist Triads: Assessing the Influence of Kin Groups on Civil Wars.” World Politics 61, no. 3 (2009): 403–37.

Cederman, Lars-Erik, K. S. Gleditsch, I. Salehyan, and J. Wucherpfennig. “Transborder Ethnic Kin and Civil War.” International Organization 67, no. 2 (2013): 389–410.

Collier, Paul, and A. Hoeffler. Greed and Grievance in Civil War. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2000.

———. “Greed and Grievance in Civil War.” Oxford Economic Papers 56, no. 4 (2004): 563–95.

Cunningham, David. “Blocking Resolution: How External States can Prolong Civil War.” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 2 (2010): 115–27.

———. “Veto Players and Civil War Duration.” American Journal of Political Science 50, no. 4 (2006): 875–92.

Cunningham, David E., K. S. Gleditsch, and I. Salehyan. “It Takes Two: A Dyadic Analysis of Civil War Duration and Outcome.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 53, no. 4 (2009): 570–97.

———. Non–State Actor Data – Version 3.3., 2009.

Davis, David R., and W. H. Moore. “Ethnicity Matters: Transnational Ethnic Alliances and Foreign Policy Behavior.” International Studies Quarterly 41, no. 1 (1997): 171–84.

Deutsch, Karl W. “External Involvement in Internal War.” In Internal War: Problems and Approaches edited by H. Eckstein, 100–10. New York: Free Press, 1964.

Dixon, Jeffrey S., and M. R. Sarkees. A Guide to Intra–state Wars: An Examination of Civil, Regional, and Intercommunal Wars, 1816–2014. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2016.

Easton, David. The Political System. An Inquiry into the State of Political Science. New York: Knopf, 1953.

Fearon, James D. “Civil War and the Current International System.” Daedalus 146, no. 4 (2017): 18–32.

Fearon, James D., and D. D. Laitin. “Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War.” American Political Science Review 97, no. 1: 75–90.

Gasiorowski, Mark J. “Regime Legitimacy and National Security: The Case of Pahlavi Iran.” In National Security in the Third World: The Management of Internal and External Threats, edited by E. E. Azar and C.-in Moon, 227–50. Cambridge, University of Maryland, 1988.

Gleditsch, Kristian S. “Transnational Dimensions of Civil War.” Journal of Peace Research 44, no. 3 (2007): 293–309.

Gleditsch, Nils Petter, P. Wallensteen, M. Eriksson, M. Sollenberg, and H. Strand. “Armed Conflict 1946–2001: A New Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 39, no. 5 (2002): 625–37.

Gurr, Ted R. Why Men Rebel. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1968.

Högbladh, Stina, T. Pettersson, and L. Themné. “External Support in Armed Conflict 1975–2009.” Paper presented at the 52nd Annual International Studies Association Convention, Montreal, Canada, 2011.

Kalyvas, Stathis N., and L. Balcells. “International System and Technologies of Rebellion: How the End of Cold War Shaped Internal Conflict.” American Political Science Review 104, no. 3 (2010): 415–29.

Lemke, Douglas, and W. Reed. “The Relevance of Politically Relevant Dyads.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 45, no. 1 (2001): 126–44.

Lyall, Jason, and L. C. I. Wilson. “Rage against the Machines: Explaining Outcomes in Counterinsurgency Wars.” International Organization 63, no. 1 (2009): 67–106.

Mahavera, Sheridan. “Border Alert for Arms Mastermind.” New Straits Times, August, 30, 2003.

Maoz, Zeev, and B. D. Mor. “Enduring Rivalries: The Early Years.” International Political Science Review 17, no. 2 (1996): 141–60.

Maoz, Zeev, and B. Russett. “Normative and Structural Causes of Democratic Peace, 1946–1986.” American Political Science Review 87, no. 3 (1993): 624–38.

Maoz, Zeev, and B. San–Akca. “Rivalry and State Support for Non–state Armed Groups (NAGs).” International Studies Quarterly 56, no. 4 (2012): 720–34.

Marshall, Monty G., and K. Jaggers. “Polity IV Project:Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800–2007.” Center for Systemic Peace, Vienna, VA, 2009.

Merriam, Charles E., and H. F. Gosnell. Non–Voting, Causes and Methods of Control. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1924.

Owen, John Malloy I. The Clash of Ideas in World Politics: Transnational Networks, States, and Regime Change, 1510–2010. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Piazza, James A. “Is Islamist Terrorism More Dangerous?: An Empirical Study of Group Ideology, Organization, and Goal Structure.” Terrorism and Political Violence 21, no. 1 (2009): 62–88.

Popper, Karl. The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Routledge Classics, 2002[1959].

Regan, Patrick M. “Conditions of Successful Third–Party Intervention in Intrastate Conflicts.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 40, no. 2 (1996): 336–59.

———. “Third-Party Interventions and the Duration of Intrastate Conflicts.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 46, no. 1 (2002): 55–73.

Richardson, Lewis Fry. Statistics of Deadly Quarrels. Boxwood Press, 1960.

Saideman, Stephen M. “Discrimination in International Relations: Analyzing External Support for Ethnic Groups.” Journal of Peace Research 39, no. 1 (2002): 27–50.

———. “Explaining the International Relations of Secessionist Conflicts: Vulnerability vs. Ethnic Ties.” International Organization 51, no. 4 (1997): 721–53.

———. The Ties That Divide: Ethnic Politics, Foreign Policy, and International Conflict. New York: Colombia University Press, 2001.

San-Akca, Belgin. “Dangerous Companions: Cooperation between States and Nonstate Armed Groups.” NAGs Dataset v.04/2015. Koç University, Istanbul, April 2015. nonstatearmedgroups.ku.edu.tr.

———. “Democracy and Vulnerability: An Exploitation Theory of Democracies by Terrorists.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 58, no. 7 (2014): 1285–310.

———. States in Disguise: Causes of State Support for Rebel Groups. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

———. “Supporting Non–State Armed Groups: A Resort to Illegality?” Journal of Strategic Studies 32, no. 4 (2009): 589–613.

Sarkees, Meredith Reid, and F. Wayman. Resort to War: 1816–2007. Washington DC: CQ Press, 2010.

Sawyer, Katherine, K. G. Cunningham, and R. Reed. “The Role of External Support in Civil War Termination.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59 (2015): 1–29.

Singer, J. David, and M. H. Small. “Correlates of War Project: International and Civil War Data, 1816–1992.” ICPSR Study # 9905. Ann Arbor, MI: ICPSR, 1994.

Wood, Reed M. “From Loss to Looting? Battlefield Costs and Rebel Incentives for Violence.” International Organization 68, no. 4 (2014): 979–99.

Wright, Quincy. Study of War. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964.