Yong-Soo Eun

Hanyang University

This article shows that the problem of “West-centrism” in the study of International Relations (IR) is synonymous with the problem of the dominance of positivism, a particular version of science that originated in the modern West. How can we open up this double parochialism in IR? The article calls for reflexive solidarity as a way out. This indicates that on-going Global IR projects need to revamp their geography-orientated approaches and instead seek solidarity with other marginalised scholars irrespective of their geographical locations or geocultural backgrounds to build wide avenues in which not only positivist (i.e., causal-explanatory) inferences but also normative theorising and ethnographically attuned approaches are all accepted as different but equally scientific ways of knowing in IR. As a useful way of going about this reflexive solidarity, this article suggests autobiography.

1. Introduction:“West-centrism” in IR

It is by now a well-run argument that International Relations (IR), as a discipline, is a Western-dominated enterprise. IR scholarship has long focused on and attached importance to great power politics based on “the Eurocentric Westphalian system” [1]; much of mainstream IR theory is “simply an abstraction of Western history.”[2] Furthermore, non-Western scholars have been excluded from “the mainstream of the profession” of IR.[3] Additionally, IR continues to seek “to parochially celebrate or defend or promote the West as the proactive subject of, and as the highest or ideal normative referent in, world politics.”[4] Let us take our pedagogical practice as a case in point. Based on an analysis of what is taught to graduate students at 23 American and European universities, Hagmann and Biersteker have found that “the none of the 23 schools surveyed draws on non-Western scholarship to explain international politics. World politics as it is explained to students is exclusively a kind of world politics that has been conceptualized and analysed by Western scholars.”[5] Publishing provides another case in point. A recent empirical study shows that “hypothesis-testing” works by American and other Global North scholars are published “approximately in proportion to submissions” in flagship political science and IR journals, while Global South scholars “fare less well” in the review process.[6] In fact, all the Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP) survey data from February 2014 to December 2018 clearly show that a large majority of academics surveyed in 36 countries view IR as a Western/American-dominated discipline.[7]

2 A Response: “Non-Western” IR

It should therefore come as no surprise that many critical IR scholars have called for “broadening” the discipline of IR beyond “the current West-centrism.”[8] One of the early responses to this call was to draw renewed attention to non-Western societies’ histories, cultures, and philosophies and incorporate them in the theorisation of international relations; in this context, not only the question of whether there are any substantial merits to developing a “non-Western” IR theory, but also what such a theory would (or should) look like have now been placed front and centre of the debate. Of course, as will be discussed in detail in the following section, contemporary events such as the rise of China have contributed to the development of non-Western (or indigenous) theories and concepts.[9]Advocates of Chinese IR and (by extension) non-Western IR theory building often point out that Asia has histories, cultures, norms, and worldviews that are inherently different from those derived from or advanced in Europe.

This idea also has resonance with discontent with the epistemic value of mainstream IR theories, namely realism, liberalism, and constructivism, all of which have Western—or, more specifically, “Eurocentric”[10]—ontological, epistemological, and/or normative underpinnings.[11] Western theories, the criticism goes, misrepresent and therefore misunderstand much of “the rest of the world.”[12] It is in this respect that Amitav Acharya and Barry Buzan have put together a special issue and a follow-up edited volume[13], asking “Why is there no non-Western international theory?” despite the fact that “the sources of international relations theory conspicuously fail to correspond to the global distribution of its subjects.”[14] Since Acharya and Buzan’s seminal forum was published, there have been a great deal of studies that aim to develop new and indigenous theories through (re)discovering and conceptualising non-Western IR communities’ lived experiences and vernacular perspectives.

Yaqing Qin at the China Foreign Affairs University states that Chinese IR theory “is likely and inevitably to emerge along with the great economic and social transformation that China has been experiencing.”[15] The scholarly practices of building an IR theory “with Chinese characteristics” are a case in point. Although consensus on what “Chinese characteristics” actually are has yet to be determined, many scholars hold that the establishment of a Chinese IR theory or a “Chinese School” of IR is desirable or “natural”;[16] in this light, Confucianism, “Chinese Marxism,” Tianxia, Zhongyong, Wang Dao, Guanxi, and the Chinese tributary system, are all cited as theoretical resources for Chinese IR.[17]

3. Evolution: “Global IR”

As is clear from the above, there has been a great deal of interest in addressing Western-centric IR; this trend includes a strong and increasing commitment to the development of non-Western or indigenous IR theories among Chinese IR scholars. At the same time, however, a number of criticisms have been raised against attempts to develop non-Western IR. For example, critics point out that although theory-building enterprises in non-West contexts commonly begin by problematising Western-dominated IR, the ongoing scholarly practices and discourses associated with non-Western IR can also entail (or reproduce) the same hierarchic and exclusionary structure of knowledge production, which can fall prey to particular national interests. In this regard, William Callahan doubts the applicability of Tianxia. In his discussion of Chinese visions of world order, he claims that what the notion of Tianxia does is “blur” the conceptual and practical “boundaries between empire and globalism, nationalism, and cosmopolitanism”. Rather than help us move towards a “post-hegemonic” world, Tianxia serves to be a philosophical foundation upon which “China’s hierarchical governance is updated for the twenty-first century.”[18] Relatedly, Andrew Hurrell[19] has added that although developing culturally specific ways of understanding the world “undoubtedly encourages greater pluralism,” attempts to do so can also lead to a national and regional “inwardness” that works to reproduce the very “ethnocentricities” that are being challenged.

These concerns about the potential nativist undercurrent of the non-Western IR theory-building enterprise are indeed shared by those who pay greater attention to the issue of the West/non-West (self-other) binary when it comes to opening up the parochial landscape of IR. “Global IR” is worthy of lengthy note in this regard.

The idea of “Global IR” was first introduced by Amitav Acharya. In his presidential address at the annual convention of the International Studies Association in 2014, Acharya explained what Global IR is or should be. His background assumption is this: IR does “not reflect the voices, experiences … and contributions of the vast majority of the societies and states in the world, and often marginalize those outside the core countries of the West.”[20] Yet, instead of arguing for a counter (i.e. anti-Western) approach, he presented the possibility of a global discipline that transcends the divide between “the West and the Rest.” In his views, IR should be a “truly inclusive” discipline that recognises its multiple and diverse foundations and histories. In this respect, the Global IR project sets out to safeguard against a tug of war between Western and non-Western IR and the subsumption of one of them in favour of the other. Being wary of both problems, namely the current West-centrism of IR and the potential danger of nativism in non-Western IR theorisation, it attempts to render international relations studies more inclusive and pluralistic. While recognition and exploration of local experiences of non-Western societies as yet-to-be discovered sources of theory-building is being encouraged, the Global IR project also reminds us that scholarly enterprises of this kind should not lead to a nativist or self-centred binary thinking.[21] What Global IR scholarship ultimately seeks is to render our discipline more inclusive and pluralistic; in this respect, there is emerging literature on “dialogue” beyond the West/non-West distinction in the Global IR debate.[22]

In sum, in order to address the problem of West-centrism, many IR scholars have long attempted to broaden the theoretical and discursive horizons of IR, and those attempts have gone by various names, including “non-Western IR,” “post-Western IR,” and “Global IR.” Different though the approaches are, the concern common to all of them is to promote “greater diversity” in IR knowledge and knowledge production through embracing a wide range of histories, experiences, and theoretical perspectives, particularly those from outside the West.

4. Taking Stock of Research Trends in East Asian IR Communities[23]

A key question, then, is whether and to what extent these attempts to open the discipline to new perspectives or theories have paid off. To find the answer, I look at research trends in the IR communities of three key East Asian countries, namely China, Korea, and Japan, examining their theoretical and epistemological orientations. In particular, I compare them with those of mainstream (i.e. American) IR. As discussed above, Chinese IR scholars tend to be discontent with West-centrism, particularly the “US parochialism”[24]; correspondingly, they have been trying to develop an alternative IR theory with “Chinese characteristics” for the past two decades or so. In addition, several scholars have expected that “growing interest in IR outside the core [i.e. the United States], in particular, in ‘rising’ countries such as China,” would lead to the waning of American disciplinary power while opening up new spaces for the study of international relations.[25] For these reasons, there has been a reasonable anticipation that theoretical or epistemological approaches employed by the Chinese IR community are markedly different from American IR, and that Chinese scholars will make the field more colourful or critical. Given these, a careful examination of where East Asian IR communities, particularly Chinese IR scholarship, currently stand in comparison to American IR scholarship is a reasonable way to see the extent to which attempts to go beyond Western/American parochialism and promote “greater diversity” in IR knowledge have paid off.

4.1. American IR scholarship (as a point of comparison)

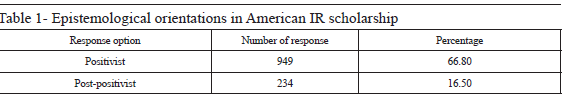

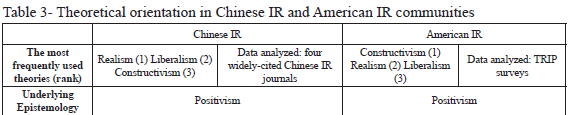

According to the comprehensive research of Daniel Maliniak and his colleagues, which analyses recent trends in IR scholarship and pedagogy in the United States using the TRIP survey data, the American IR community appears to enjoy “theoretical” diversity in the sense that no single theoretical paradigm dominates the community. It is a “limited” form of diversity, however, based on a clear commitment to positivism. Maliniak et al.’s study demonstrates that more than 70 percent of the contemporary IR literature produced in the United States falls within the three theoretical paradigms—realism, liberalism, and “conventional” constructivism—all of which lie within the epistemological ambit of positivism. Of course, constructivists are less likely to adopt positivism than scholars working within the other two theoretical paradigms; yet “most of the leading constructivists in the United States… identify themselves as positivist.”[26] More specifically, around 70 percent of all American IR scholars surveyed describe their work as positivist. Furthermore, younger IR scholars are more likely to call themselves positivists: “sixty-five percent of scholars who received their Ph.D.s before 1980 described themselves as positivists, while 71 percent of those who received their degrees in 2000 or later were positivists.”[27]

The data of the most recent TRIP survey conducted in 2017 also shows that American IR scholarship remains strongly committed to positivism (see tables below).[28] More specifically, with respect to epistemological foundation, around 67 percent of all American IR scholars surveyed characterise their work as positivist. This result corresponds to theoretical orientations in the American IR community: they are confined to the three positivist theoretical paradigms, namely constructivism, realism, and liberalism. To be sure, there are several post-positivist variants within constructivism; yet American IR scholars are committed to one particular version of constructivism, namely the “conventional” one, and thus their constructivist work focuses mainly on social norms and institutions (60 percent) in lieu of “society,” as the former are believed to be “more readily characterized and analyzed as measurable dependent and independent variables.”[29]

The fact that positivism remains the dominant influence in the American IR community is also clear in the classrooms of American colleges and universities. A series of surveys conducted by the TRIP project shows that IR faculty in the United States devote a great deal of time in introductory IR courses to the study or application of positivist theories, particularly realism. While its share of class time may have declined, realism still dominates IR teaching in the United States. For example, 24 percent of class time in 2004, 25 percent in 2006, and 23 percent in 2008 were devoted to this paradigm; these percentages are larger than those listed for any other theoretical paradigm.[31] Not surprisingly, this trend is consistent with the content of American IR textbooks. Elizabeth Matthews and Rhonda Callaway’s content analysis of 18 undergraduate IR textbooks widely used in the United States demonstrates that most of the theoretical coverage is devoted to realism, followed by liberalism, with constructivism a distant third.[32] In short, although interest in grand theory (i.e. theoretical paradigms) has decreased in recent years, the three theoretical paradigms, namely realism, liberalism, and conventional constructivism, continue to remain the dominant influences in American IR scholarship,[33] and there is a persistent and strong commitment to positivism as a “scientific” approach to knowledge production among American IR scholars.

4.2. Chinese IR scholarship

In order to determine what theoretical paradigms Chinese IR scholarship is committed to and what epistemological orientations it has, our research team first searched the databases of four widely-cited IR journals within the Chinese academy—World Economics and Politics, Foreign Affairs Review, Contemporary International Relations, and China International Studies—and then analysed the abstracts of all of the Chinese articles published in these journals over the past in the last 10 years (2010–2020). The results show that 73 percent of the articles analysed fit within the three mainstream theories: realism (31%), particularly balance of power theory and power transition theory, liberalism (25%), and constructivism (17%). By contrast, only nine percent of the articles analysed discuss Chinese IR-related concepts and ideas, such as Tianxia, Zhongyong, Wang Dao, moral realism, Confucianism, Confucius, Xunzi or Hanfeizi.[34]

These findings indicate that intellectual resources connected with home-grown Chinese IR theories, namely Qin Yaqing’s relational theory, Yan Xuetong’s moral realism, and Zhao Tingyang’s Tianxia theory,[35] do not make a significant impact on how Chinese scholars conceptualise or analyse international relations. Furthermore, the fact that the three mainstream (Western/American-derived) IR theoretical paradigms remain dominant influences in the Chinese IR community also indicates that their epistemological understanding of what “scientific” or “valid” studies of international relations should entail is largely grounded in positivism, a particular version of science.[36] Even in discussions on building an IR theory with “Chinese characteristics,” several Chinese IR scholars state that such an indigenous theory “should seek universality, generality” in order to be recognized as a “scientific” enterprise.[37] For example, Yan Xuetong, one of the key contributors to the development of a Chinese IR theory, emphasises the importance of scientific approaches, which he defines in positivist terms.[38]

In short, the emerging Chinese IR scholarship is very much in line with American IR: both are based largely on the three positivist theories, namely realism, liberalism, and conventional constructivism. Irrespective of the intentions to develop an indigenous Chinese theory, this trend contributes to consolidating the hegemonic status of positivist international studies and the institutional preponderance of American IR.

4.3. Are other East Asian IR communities different?

Interestingly, and unfortunately from the perspective of advocates of non-Western or Global IR, a lack of attention to alternative or indigenous IR studies is also visible in other East Asian IR communities. In our analyses, my research team focused on the Korean and Japanese IR communities given their relatively large numbers of IR scholars, as well as their countries’ political and economic powers in the region. In the case of Korean IR scholarship, we examined the abstracts of all the articles published in the Korean Journal of International Relations (KJIR), the most-cited Korean IR journal, between 2010 and 2020. The results show that the three mainstream theories remain at the center of discussion: of the 211 theoretical articles analyzed, 85 percent (179 articles) are devoted to realism, constructivism or liberalism while virtually no studies discuss Chinese IR. More specifically, 71 articles are on realism, 62 articles are on constructivism, and 46 articles are on liberalism. None of the analysed articles discuss the key terms of Chinese IR: Tianxia, Zhongyong, Wang Dao, moral realism, Confucianism, Confucius, Xunzi or Hanfeizi.[39]

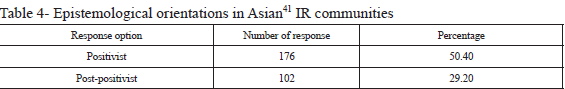

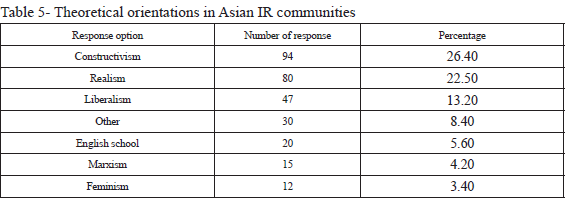

On the contrary, IR theory-building enterprises in South Korea show patterns very similar to those found in the US. On the one hand, Korean IR scholars, as has been the case in China, problematise contemporary IR, noting that the discipline is too American/Western-centric. On the other hand, however, they explore how to develop an alternative IR theory and how to judge its success largely from a positivist perspective, considering “generalization” as the ultimate reference point. In other words, that “any theorizing based on Korea’s unique historical experiences must be tested under the principle of generality” is a major undercurrent in the existing discussion about “Korean IR.” Correspondingly, when the meaning (or purpose) of theory is taught or discussed in an IR classroom in Korea, what is largely invoked is a “positivist” understanding of the role of theory, namely “generalizability.”[40] This trend—that positivism serves as an epistemological foundation upon which to base research, and thus theoretical analysis is narrowly confined to the three theoretical perspectives of realism, liberalism, and conventional constructivism—is also confirmed by the most recent TRIP survey data on other Asian IR communities (see the following tables).

The “Asian” countries surveyed include Hong Kong, Japan, Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore [41]

The “Asian” countries surveyed include Hong Kong, Japan, Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore [41]

In sum, although the Global IR projects have received significant attention, generating alternative or indigenous sources for theory construction (especially in China), a few Western IR theories still remain at the centre of many Asian IR scholarships. Worse, there is little difference between epistemological trends in the American and Asian (Chinese, Korean, and Japanese) IR communities in terms of their strong commitment to positivist epistemology. This results in the predominance of a positivism-centred understanding of what counts as a “good” theory or a “valid” way of producing knowledge in IR. In other words, despite the facts that the once-dominant positivism has met its demise in the philosophy of science and that the philosophy of science embraces a wide variety of “legitimate” understandings of “science,”[42] positivism continues to “usurp” the title of science in IR.

5.Reflexive Solidarity in Global IR

What the above discussion and investigation indicate is clear: the problem with the parochialism of IR, which concerns all those engaged in Global IR, is not only geographical or geocultural. Western/American dominance in the field can also be seen in the dominance of positivism, a particular version of science that originated in the modern West. A few theoretical paradigms based on positivism continue to prevail across different (whether Western or non-Western) IR communities. As discussed earlier, even those concerned with going beyond the West-centrism of IR by developing indigenous (Asian) theories or “national schools” tend to do so on the basis of a general acceptance of the positivist model of science. While expressing deep concerns about the “marginalisation” of non-Western scholarships within the field, they consider positivism as the standard way of conducting inquiry in IR. In this respect, the problem of the dominance of the West in IR is synonymous with the problem of the dominance of positivism. How can we address this double parochialism in IR? I call for reflexive solidarity—as both a reflexive and intentional pivot to the “science question” and a collaborative move toward a broadening of what it means to be “scientific” in global IR knowledge.

5.1. The “science question” in IR

Obviously, it is very important to pay sustained attention to indigenous knowledge and experiences and theorise them in the study of international relations. Yet, equally importantly, such an undertaking should not resort to the geography-orientated ways of addressing the complex issue of IR’s marginalisation and parochialism. The ongoing non-Western or Global IR debates tend to approach West-centrism narrowly in geocultural terms—i.e. in terms of the geographical origins of key IR concepts, theories, or theorists. For example, non-Western IR theory-building enterprises, especially those committed to the establishment of “national school,” tend to situate their rationales along the simple binary geographical or geohistorical lines: either inside or outside of the West. Similarly, many advocates of Global IR begin their quest with geocultural concerns. In this sense, Wemheuer-Vogelaar et al. note,[43] “geography plays a central role in the Global IR debate,” and its literature “repeatedly categorizes scholars into … regional and national schools.” Interestingly, their study, based on the 2014 TRIP survey data, shows that non-Western IR scholars “are more likely to have geographically bounded perceptions of IR communities” than their Western counterparts.[44] Of course, it is true that non-Western societies and their voices sit on the margins of the discipline; we must grapple with this marginalisation and underrepresentation. The point is not that these geographically-based concerns are misplaced, but that the current terrain of the Global IR debate needs to extend to the issues of epistemology (i.e. the “science question”) in order to see the extent of the parochialism of IR more clearly, and thus ameliorate it. That is, we need to critically reflect on ourselves, asking whether our research and teaching practices have been rich enough to go beyond the mainstream (i.e. positivist) view of science and do justice to a pluralistic understanding of what it means to be “scientific” (and thus “legitimate” and “good”) knowledge in IR. This critical self-reflection is necessary given that there is only one dominant epistemological view prevailing across IR communities.

Positivism, as a particular philosophy of science, does not accept local perspectives or indigenous experiences as a secure foundation upon which to produce and ensure any scientific knowledge. In positivist conceptions of science, it is “unscientific” to emphasise and/or incorporate a particular culture or the worldview of a particular nation or region into theory, for a legitimately scientific theory should seek generality and universality. Positivists maintain that “scientific” and “good” international studies ought to discern general patterns of state behaviour, develop empirically verifiable “covering law” explanations, and test their hypotheses through cross-case comparisons. Gary King, Robert Keohane, and Sidney Verba make it clear that generality is the single most important measure of progress in IR, stressing that “the question is less whether… a theory is false or not… than how much of the world the theory can help us explain.”[45] From this perspective, any attempt to develop an indigenous theory attentive to historically-situated local cultures or traditions is suspect because it may delimit the general applicability of theory.

What this implies is that attempts to globalise IR by embracing non-Western societies’ indigenous ontologies or historical-cultural traditions need to be accompanied by attempts to broaden what we mean by scientific knowledge in international studies. Unless we rectify the mistaken conflation of science (in general) with a particular (i.e. positivist) version of science, the double parochialism of IR will likely remain unchanged.

5.2. Solidarity

This is precisely where I suggest solidarity and collaboration should come in. As noted, a globalising of IR requires a broadening of the limited understanding of science in IR; to this end, the non-Western and Global IR projects need to revamp their geography-orientated approaches by seeking solidarity with other marginalised scholars, specifically post-positivists, in order to build wide avenues in which not only positivist (i.e. causal-explanatory) inferences, but also critical and normative theorising and historicised, ethnographically-attuned approaches are all accepted as different but equally “scientific” ways of knowing in IR. Furthermore, collaboration among them is logical. The view that where a theory originates and who originates it matter a great deal is shared by all forms of Global IR projects. This assumption resonates with post-positivist understandings of theory. In contrast to positivist epistemology, in which theory is thought to be objective—regardless of where and by whom a theory is built—post-positivism emphasises that “theory is always for someone and for some purpose.”[46] In this regard, post-positivist scholarship engages in critical, normative, and constitutive theorising, as opposed to explanatory theorising. Post-positivist epistemology regards the key roles of theory as criticising a particular social order and analysing how it is constituted, with the goal of changing it. Global IR projects also intend to change the current IR scholarship, with the aim of rendering it more diverse and inclusive. Likewise, IR scholars who favour a post-positivist epistemology and reflexive theory have long entered pleas for pluralism. Thierry Balzacq and Stéphane Baele note that since the beginning of the third debate in IR, “theoretical diversity” has consistently remained “the strongest statement” of post-positivist IR scholars.[47]

What is more, several post-positivist IR researchers have already begun to develop broad conceptions of science. For example, Jackson writes that different theoretical paradigms, including the “reflexivist” paradigm, should be considered equally valid (or “scientific”) modes of knowledge in IR; to this end, he calls for “a pluralist science of IR” based on “a broad and pluralistic definition of science.”[48] His call also resonates with an attitude of “foundational prudence,” a suggestion by Nuno Monteiro and Keven Ruby. They state that IR researchers need to remain “open-minded” about ontological and epistemological foundations on which to build “scientific” grounds for producing knowledge, which thus “encourages theoretical and methodological pluralism” in IR.[49] In a related vein, Stefano Guzzini has proposed four modes of theorising—“normative, meta-theoretical, ontological/constitutive, and empirical”—each of which has a different yet connected “scientific” purpose.[50] Milja Kurki has also made a significant contribution to rectifying our narrow view of science and causation: building upon the conceptualisation of cause and causation advanced by critical realism, her work shows that causes can work in many different ways beyond a ‘when A, then B’ form, such ways as producing, generating, creating, constraining, enabling, influencing or conditioning.[51] Non-Western and Global IR enterprises need to engage in more active dialogue with these post-positivists’ critical discussions about science and jointly open up broad avenues for determining what can count as “valid” forms of evidence and “scientific” knowledge in IR. Given all of the above, solidarity between those concerned with going beyond the West-centrism of IR and those embracing post-positivist epistemology is not just possible, but also necessary if we are to change the parochial landscape of IR and ultimately achieve a “truly” pluralistic and global IR.

5.3. Autoethnography: Praxis of reflexive solidarity

Here, an autoethnographic or autobiographical approach[52] can be very useful for actually ‘doing’ reflexive solidarity, especially with the aim of evoking entangled empathy and solidarity.[53] As discussed earlier, Global IR scholarship constantly calls for “change,” emphasising the need to embrace a wider range of theoretical, historical, or normative perspectives in international studies. When our motivation is to change the current state of IR, a key step that must be taken is to “share our feelings and thoughts with others.”[54] Obviously, this sharing can only begin after telling our own stories. In effect, to reveal the personal is the very first step in any encounter with others. For example, how much do I—as a non-Western (Asian) IR researcher and teacher motivated to change a Western-centric IR—put my motivation/intention into action in teaching and research? What has made me feel discouraged and frustrated when I tried to globalise IR, using and promoting local knowledge and indigenous historical experience and literature? That is, we need to reflect on ourselves by telling our personal experiences—struggles, challenges, frustrations—rather than making generalised statements on what others think or what institutional and structural constraints are as if we are an ‘objective’ analyst, observing the issue at hand with a bird’s-eye view.

Surely, this is not to suggest that what is at stake in bringing about “greater diversity” in IR is only the personal. It is imperative to understand broader socio-political norms and institutional contexts that condition or constrain the acts of individuals living therein. But, again, the key here is to see social or institutional contexts through our own personal encounters. For instance, how has my personal and professional subjectivity been constructed, deconstructed, or reconstructed within and through the prevailing norms of the IR community or the nation of which I am also a member?[55] What has encouraged or discouraged my attempts and practices to change the existing social norm or institutional makeup? How are my research and teaching practices implicated in the production or reproduction of my local IR community? In short, when we discuss social and institutional constraints that impede our motivation and action to embrace “greater diversity” in IR research and teaching, what is crucial is to tell our stories (personal encounters and struggles) that pass through the social constraints. “To write individual experience is, at the same time, to write social experience.”[56]

This autoethnographic approach, namely to write about the self (i.e. what experiences I have had and what emotions I have felt), does help to create empathy.[57] When our stories are being told, others can always find threads of their own stories in ours. And the minute that recognition happens, it becomes the basis for the solidarity necessary for change in IR. Whenever I tell my personal stories about what made me struggle and why I felt frustrated or discouraged when I sought “doing IR differently” in the Korean academic community where positivist theories remain the dominant influence, I see my stories travelling far beyond the national or geocultural boundary, having a great resonance with others who also seek “doing IR differently” yet struggle with the prevailing norms of their local IR communities. That is, a revealing of the feeling-self is a very effective way to confront the multiple identities that we possess (yet often limit to one particular stratum) and find linkages across various socio-political boundaries. This is the virtue of autoethnography; I suggest that advocates of Global IR can and should use autoethnographic narratives of their everyday lived experiences, be they achievements or frustrations, to understand, critique, and change the current parochial state of IR.

6. Concluding Remarks

The extent of parochialism in IR knowledge and knowledge production can and should be examined according to various dimensions, including epistemological as well as geographical or geocultural. Unfortunately, however, the epistemology closely associated with our understandings of and approaches to science, and how it can be connected with the issue of parochialism or marginalisation, does not receive the attention it deserves in the Global IR debate. This is a serious limitation precisely because the problem we face is a double parochialism. For example, if we consider the problem of the hierarchy of knowledge not only from a geographical perspective (i.e. Western/American-centrism), but also in terms of epistemology (i.e. positivism’s dominance of the field), then the Global IR project can have far-reaching repercussions with support from post-positivist IR scholarship, whose epistemological underpinnings are marginalised irrespective of their geographical locations, be they the non-West or the West. At the same time, although a large group of post-positivist scholars express their deep concerns about the problem of hierarchies in international studies,[58] the issue of the marginalisation of knowledge production in geocultural contexts has not been raised or addressed as much as it could be in their critical and normative approaches to the problem. Put simply, while both groups are concerned with marginalisation, calling for a pluralistic field of study, their sets of concern tend to remain disparate.

In order to expand the IR discipline, the opening up of what we mean by “scientific” knowledge in IR is also vital. To move the discipline toward this broadening, critical self-reflection and collective collaboration among marginalised scholars through autoethnographic narratives and accounts are all essential. I believe that this reflexive solidarity will help to move us a step closer toward achieving a “truly” pluralistic and global IR.

Acharya, Amitav. “Advancing Global IR: Challenges, Contentions, and Contributions.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 4–15.

———. “From Heaven to Earth: ‘Cultural Idealism’ and ‘Moral Realism’ as Chinese Contributions to Global International Relations.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 12, no. 4 (2019): 467–94.

———. “Global International Relations (IR) and Regional Worlds: A New Agenda for International Studies.” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 4 (2014): 647–59.

———. “Theorising the International Relations of Asia: Necessity or Indulgence? Some Reflections.” The Pacific Review 30, no. 6 (2017): 816–28.

Acharya, Amitav, and Buzan Buzan, eds. Non-Western International Relations Theory: Perspectives on and beyond Asia. London: Routledge, 2010.

———. “Why Is There No Non-Western International Relations Theory? An Introduction.” International Relations of Asia Pacific 7, no. 3 (2007): 285–86.

———. “Why is There No Non-Western International Relations Theory? Ten Years On,” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 17, no. 3 (2017): 341–370.

Balzacq, Thierry, and Stéphane J. Baele. “The Third Debate and Postpositivism.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. 22 December 2017.

Bilgin, Pınar. “Contrapuntal Reading” as a Method, an Ethos, and a Metaphor for Global IR.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 134–46.

Breuning, Marijke, Ayal Feinberg, Benjamin Isaak Gross, Melissa Martinez, Ramesh Sharma, and John Ishiyama. “How International Is Political Science? Patterns of Submission and Publication in the American Political Science Review.” PS: Political Science & Politics 51, no. 4 (2018): 789–98.

Buzan, Buzan. “Could IR Be Different?” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 155–57.

Callahan, William A. “Chinese Visions of World Order: Post-Hegemonic or a New Hegemony.” International Studies Review 10, no. 4 (2008): 749–61.

Chen, Ching-Chang. “The Im/Possibility of Building Indigenous Theories in a Hegemonic Discipline: The Case of Japanese International Relations.” Asian Perspectives 36, no. 3 (2012): 463–92.

Cox, Robert W. “Social Forces, States and World Orders: Beyond International Relations Theory.” In Neorealism and Its Critics, edited by Robert O. Keohane, 204–54. New York: Columbia University Press, 1986.

Daniel, Maliniak, Amy Oakes, Susan Peterson, and Michael J. Tierney. “International Relations in the US Academy.” International Studies Quarterly 55, no. 2 (2011): 437–64.

Eun, Yong-Soo. “Calling for IR as Becoming-Rhizomatic.” Global Studies Quarterly 1, no. 2 (2021): 1-12.

———. “An Intellectual Confession from a Member of the ‘Non-Western’ IR Community: A Friendly Reply to David Lake’s “White Man’s IR.” PS: Political Science 52, no. 1 (2019): 78–84.

———. “Global IR through Dialogue.” The Pacific Review 32, no. 2 (2019): 131–49.

Fierke, Karin M., and Vivienne Jabri. “Global Conversations: Relationality, Embodiment and Power in the Move towards a Global IR.” Global Constitutionalism 8, no. 3 (2019): 506–35.

Gençoğlu, Funda. “On the Construction of Identities: An Autoethnography from Turkey.” International Political Science Review 41, no. 4 (2020): 600-612.

Guzzini, Stefano. “The Concept of Power: A Constructivist Analysis.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 33, no. 3 (2005): 495–521.

———. “The Ends of International Relations Theory: Stages of Reflexivity and Modes of Theorizing.” European Journal of International Relations 19, no. 3 (2013): 521–41.

Hagmann, Jonas, and Thomas J. Biersteker. “Beyond the Published Discipline: Toward a Critical Pedagogy of International Studies.” European Journal of International Relations 20, no. 2 (2014): 291–315.

Hamati-Ataya, Inanna. “Reflectivity, Reflexivity, Reflexivism: IR”s ‘Reflexive Turn’ and Beyond.” European Journal of International Relations 19, no. 4 (2012): 669–94.

———. “Transcending Objectivism, Subjectivism, and the Knowledge In-between: The Subject in/of “strong Reflexivity.” Review of International Studies 40, no. 1 (2014): 153–75.

Hobson, John. The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics: Western International Theory, 1760–2010. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Hurrell, Andrew. “Beyond Critique: How to Study Global IR?” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 149–51.

Inayatullah, Naeem, ed. Autobiographical International Relations, I, IR. London and New York: Routledge, 2011.

Inayatullah, Naeem, and Elizabeth Dauphinee, eds. Narrative Global Politics, Theory, History and the Personal in International Relations. London and New York: Routledge, 2016.

Jackson, Patrick. The Conduct of Inquiry in International Relations: Philosophy of Science and Its Implications for the Study of World Politics. London: Routledge, 2011.

Joseph, Jonathan. “Philosophy in International Relations: A Scientific Realist Approach.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 35, no. 2 (2007): 345–59.

Joseph, Jonathan, and Colin Wight, eds. Scientific Realism and International Relations. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Kim, Jong Young. Jibaebaeun Jibaeja. Paju: Dolbegae, 2015.

King, Gary, Robert O. Keohane, and Sidney Verba. Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Kristensen, Peter M., and Ras T. Nielsen. “Constructing a Chinese International Relations Theory: A Sociological Approach to Intellectual Innovation.” International Political Sociology 7, no. 1 (2013): 19–40.

Kurki, Milja. Causation in International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

———. “Stretching Situated Knowledge: From Standpoint Epistemology to Cosmology and Back Again.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 43, no. 3 (2015): 779–97.

Lake, David. “Theory Is Dead, Long Live Theory: The End of the Great Debates and the Rise of Eclecticism.” European Journal of International Relations 19, no. 4 (2013): 567–87.

———. “White Man’s IR: An Intellectual Confession.” Perspectives on Politics 14, no. 4 (2016): 1112–22.

Ling, L.H.M. “Worlds beyond Westphalia: Daoist Dialectics and the ‘China Threat.’” Review of International Studies 39, no. 3 (2013): 549–68.

Löwenheim, Oded. “The ‘I’ in IR: An Autoethnographic Account.” Review of International Studies 36, no. 4 (2010): 1025–48.

Lynch, Cecelia. “Reflexivity in Research on Civil Society: Constructivist Perspectives.” International Studies Review 10, no. 4 (2008): 708–21.

Maliniak, Daniel, Susan Peterson, and Michael J. Tierney. “TRIP Around the World: Teaching, Research, and Policy Views of International Relations Faculty in 20 Countries,” 2012. http://www.wm.edu/offices/itpir/_documents/trip/trip_around_the_world_2011.pdf.

Matthews, Elizabeth G., and Rhonda L. Callaway. “Where Have All the Theories Gone? Teaching Theory in Introductory Courses in International Relations.” International Studies Perspectives 16, no. 2 (2015): 190–209.

Monteiro, Nuno, and Keven G. Ruby. “IR and the False Promise of Philosophical Foundations.” International Theory 1 (2009): 15–48.

Murray, Christopher. “Imperial Dialectics and Epistemic Mapping: From Decolonisation to Anti-Eurocentric IR.” European Journal of International Relations 26, no. 2 (2020): 419–42.

Mykhalovskiy, Eric. “Reconsidering Table Talk: Critical Thoughts on the Relationship between Sociology, Autobiography, and Self-Indulgence.” Qualitative Sociology 19, no. 1 (1996): 131–51.

Patomäki, Heikki. “Back to the Kantian Idea for a Universal History? Overcoming Eurocentric Accounts of the International Problematic.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 35, no. 3 (2007): 575–95.

Qin, Yaqing. “Development of International Relations Theory in China: Progress through Debates.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 11, no. 2 (2011): 231–57.

———. “Recent Developments toward a Chinese School of IR Theory,” 2016. http://www.e-ir.info/2016/04/26/recent-developments-toward-a-chinese-school-of-ir-theory.

———. “A Relational Theory of World Politics.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 33–47.

———. “Why Is There No Chinese International Relations Theory.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 7, no. 3 (2007): 313–40.

Ree, Gerard van Der. “Saving the Discipline: Plurality, Social Capital, and the Sociology of IR Theorizing.” International Political Sociology 8, no. 2 (2014): 218–33.

Reus-Smit, Christian. “Beyond Metatheory?” European Journal of International Relations 19, no. 3 (2013): 589–608.

Shahi, Deepshikha. “Foregrounding the Complexities of a Dialogic Approach to Global International Relations.” All Azimuth 9, no. 2 (2020): 163–76.

Song, Xinning. “Building International Relations Theory with Chinese Characteristics.” Journal of Contemporary China 10, no. 1 (2001): 61–74.

Tickner, Arlene B. “Core, Periphery and (Neo)Imperialist International Relations.” European Journal of International Relations 19, no. 3 (2013): 627–46.

Tickner, Arlene B., and Ole Waever, eds. International Relations Scholarship around the World. New York: Routledge, 2009.

Wang, Yuan-kang. Harmony and War: Confucian Culture and Chines Power Politics. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011.

———. “Introduction: Chinese Traditions in International Relations.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 17, no. 2 (2012): 105–9.

Wemheuer-Vogelaar, Wiebke, Nicholas J. Bell, Mariana Navarrete Morales, and Michael J. Tierney. “The IR of the Beholder: Examining Global IR Using the 2014 TRIP Survey.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 16–32.

Yamamoto, Kazuya. “International Relations Studies and Theories in Japan: A Trajectory Shaped by War, Pacifism, and Globalization.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 11, no. 2 (2011): 259–78.

———. “A Triad of Normative, Pragmatic, and Science-Oriented Approaches: The Development of International Relations Theory in Japan Revisited.” The Korean Journal of International Studies 16, no. 1 (2018): 121–42.

Yan, Xuetong. Ancient Chinese Thought, Modern Chinese Power. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

———. “New Values for New International Norms.” China International Studies 38, no. 1 (2013): 1–17.

Zhang, Feng. “The Tsinghua Approach” and the Inception of Chinese Theories of International Relations.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 5, no. 1 (2012): 73–102.

Zhao, Tingyang. “A Political World Philosophy in Terms of All-under-Heaven (Tian-Xia).” Diogenes 56 (2009): 5–18.

———. The Tianxia System: An Introduction to the Philosophy of a World Institution. Nanjing: Jiangsu Jiaoyu Chubanshe, 2005.

———. “Tianxia: Can This Ancient Chinese Philosophy Save Us from Global Chaos?” Paper Presented at the Conference on ‘Global IR and Non-Western IR Theory,’ Beijing, 2018.