Fatma Aslı Kelkitli

İstanbul Arel University

International educational exchange has been used frequently as a foreign policy instrument by leading actors of the international arena since the post-Second World War years. This article on the other hand, aims to throw light on the policies and actions of a middle power; namely, Turkey, which has been designing various international scholarship programs for foreign policy ends since the early 1990s. Following a brief evaluation of the international educational exchange programs launched by the USA, Russia, the UK, the EU and China for foreign policy purposes, the study examines the Great Student Exchange Project introduced by Turkey in 1992 to carve out an influential place for itself in the South Caucasus and Central Asia. It will then delve into the Türkiye Scholarships Program, Mevlana Exchange Program and the scholarship programs of the Türkiye Diyanet Foundation, which have been introduced during the Justice and Development Party period to build up and/or boost friendly ties between Turkey and various targeted countries. The study finalizes by investigating the impact of these scholarship programs on the realization of Turkey’s foreign policy goals by exploring to what extent the sending countries align their foreign policy preferences with those of Turkey through analysis of their voting behaviours in the United Nations General Assembly.

1.Introduction

The higher education period denotes a significant and determining stage in the life of an individual. It is during those years that people acquire the theoretical and/or applied information which is deemed requisite for their professional life. They also build social bonds, some of which may endure in the succeeding years. Furthermore, it is mostly on the university campus that people are equipped with the academic and intellectual wherewithal through the lens of which they grasp the dynamics and workings of the world. This informative, constructive and transformative feature of higher education has led foreign policy makers to take it into serious consideration as an important soft power tool, particularly since the Cold War years.

The soft power of a country, which was defined by Joseph Nye as getting other countries to want what it wants,[1] is based on three resources: culture; political values; and government policies.[2] The cultural aspect of soft power has many manifestations, such as art, education, literature and mass entertainment.[3] Since the post-Second World War period, education has been utilized substantially by leading powers of the world such as the United States of America (USA), Russia, the United Kingdom (UK), the European Union (EU) and China, in the form of offers of scholarships and academic exchange programs to students of countries that were on their radar owing to foreign policy priorities.

International educational exchanges as a soft power instrument serve mainly three goals. Firstly, they enhance mutual understanding between the sending and host countries. Exchange students and/or scholars are given the opportunity to get first-hand knowledge about the political system, institutions, values, and socio-cultural characteristics of the host country, which reduces the likelihood of misinformation, prejudices and stereotyping, and thus helps to forge a solid and stable political association between the parties. Secondly, some foreign students who study in higher education institutions of the host country may subsequently take up positions of authority in their home countries and continue to retain close links with the host country. These people may be instrumental to diffuse the host country’s world view, values and practices to the masses in their home countries and elicit sympathy among the public towards the host country.[4] Finally, the positive inclinations of these potential future elites towards the host country may induce them to back up some of the foreign policy moves of the host country.

Concomitant to the civilianization of domestic politics that gained speed following the commencement of EU accession negotiations in October 2005 and a gradual desecuritization of its foreign policy with the advent of a ‘zero problems with neighbours’ approach, Turkey started to invest more seriously in its soft power potential.[5] International educational exchange in this vein became a significant soft power tool employed by Turkish foreign policy makers. Turkey launched the government-funded Türkiye Scholarships Program in 2012, which welcomed international students at undergraduate and graduate levels to study in Turkey. The introduction of the Mevlana Exchange Program, which was designed for exchange of students and academics between Turkish higher education institutions and the rest of the world, followed shortly. Furthermore, the Türkiye Diyanet Foundation, which was set up in 1975 to support the activities of the Presidency of Religious Affairs of Turkey, increased its quotas for international scholarship students at both the undergraduate and graduate levels, and opened up many higher education institutions abroad.

This study aims to examine to what extent these international educational exchange programs have contributed to the enhancement of mutual understanding and to the foundation of friendly relations between Turkey and the sending countries. A suitable way to gauge this is to find out whether these sending countries are propping up Turkey’s foreign policy moves. Studies which concentrate on appraising Turkey’s utilization of international educational exchange programs for foreign policy ends are scarce. Lerna Yanık’s[6] article assesses the intent of the international educational exchange programs introduced by Turkey in the early post-Cold War period. Pınar Akçalı and Cennet-Engin Demir’s[7] work scrutinizes the international educational programs of Turkey in the Turkic Republics of Central Asia and Caucasus in the post-Soviet era in terms of their successes and failures from the viewpoints of some of the relevant policy makers in this field as well as experts from various think-tank institutions in Turkey. Gözde Yılmaz’s article focuses on the underpinnings of the Mevlana Exchange Program and argues that it is inspired by the EU’s Erasmus program,[8] whereas Bülent Aras and Zulkarnain Mohammed’s article investigates the role of the Türkiye Scholarships Program in diffusing Turkey’s soft power.[9] However none of these four studies probes through empirical means the impact of international educational exchange programs on the realization of Turkey’s foreign policy objectives. This study intends therefore to make a contribution to the literature by investigating to what extent sending countries align their foreign policy preferences with those of Turkey, through an analysis of their voting behaviour in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA).

This article is divided into three parts. The first part explores the international educational exchange programs initiated by the USA, Russia, the UK, the EU and China to further their foreign policy goals, and which served as inspiring examples for Turkey’s similar efforts. The second part starts with a review of Turkey’s endeavour in the early 1990s to make use of international educational exchanges in order to raise its profile in the neighbouring regions, by examining the Great Student Exchange Project. It then moves on to the Türkiye Scholarships Program, Mevlana Exchange Program, and the scholarship programs of the Türkiye Diyanet Foundation, all launched by the Justice and Development Party (JDP) government, and aims to explore the activities they have carried out to help the establishment of closer ties between Turkey and the sending countries. The last part scrutinizes the impact of these international educational exchanges on actualization of Turkey’s foreign policy goals. Accordingly, this part compares and contrasts the voting behaviour of sending countries in the UNGA to the voting preferences of non-sending states between the years 1985 and 2018 in order to find out the extent of foreign policy convergence between Turkey and the sending countries over the long-term.

2. International Educational Exchange in the Service of Foreign Policy Goals: Examples from the USA, Soviet Union/Russia, the UK, the EU and China

The post-Second World War epoch witnessed the emergence of a fierce competition between the USA and the Soviet Union in political/ideological, economic, and military dimensions. Washington started to embark on the fourth dimension, the cultural aspect,[10] following the unveiling of the Fulbright Act of 1946 and the Smith-Mundt Act of 1948. These two documents, which aimed to increase the USA’s understanding of other countries and their understanding of the USA and promote cooperative international relations, envisaged the financing of international educational exchange programs by the USA government.

The partakers of these educational exchange programs would gain exposure to the USA’s scientific and technological achievements, its liberal democratic political system, as well its material wealth. American accomplishments in higher education, political freedom, and economic well-being were expected to impress these people, generate feelings of appreciation and friendliness towards the USA and instigate them to initiate policies and practices in their home countries similar to the American ones. Leadership potential along with academic excellence became the key determinants for the selection of the scholarship holders, as the participants were considered as culture carriers who would create a multiplier effect by influencing other people in their own societies. So, it is not surprising that 37 Fulbright alumni have served as heads of state or government.[11]

The Cold War years also witnessed the utilization of international educational exchanges for foreign policy ends by the Soviet Union. Starting in the mid-1950s, the Soviet Union had set its sights on the newly independent states of Africa, Asia, and Latin America and began offering higher education scholarships to acclimatize the prospective leadership cadres of these countries to communist ideas along with Russian language and culture. Another significant endeavour in this direction was the opening of the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia in Moscow on 5 February 1960, which offered higher education programs to foreign students, especially to those coming from developing countries, as an extension of humanitarian aid. Presidents, prime ministers, political party leaders, ambassadors and intellectuals from many African, Asian and Latin American countries can be named among the notable alumni of this university.[12]

Higher education has also been appraised as one of the significant soft power tools of the Russian Federation, the successor state of the Soviet Union. The Russian government provides scholarships to 15,000 international students on a yearly basis, which includes free tuition, maintenance allowance, and dormitory accommodation.[13] These scholarship programs are expected to help the formation of “pro-Russian national elites” who will be of great value to building good rapport between Russia and their home countries.[14]

The UK designed an international postgraduate scholarship program in 1983 with financial support from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and partner organizations. The Chevening Scholarship Program aims to support the UK’s foreign policy goals “by creating lasting positive relationships with future leaders, influencers, and decision-makers”.[15] Accordingly, among the program’s nearly 50,000 alumni there exist presidents, prime ministers, ministers, members of parliament, party leaders, ambassadors, writers and journalists.[16]

The EU came forth with its postgraduate scholarship program, Erasmus Mundus, in 2009. The program, which has fallen under the Erasmus+ program as a result of the reorganization process in 2014, offers joint masters and doctorate degree education packages to international students in two or more higher education institutions in the EU.[17] The participants of the scholarship program are defined by former President of the European Commission Jose Manuel Barroso as the EU’s best ambassadors,[18] and are expected to help the foundation of better ties between their home countries and the Union.

China’s offer of scholarship programs to international students kicked off in the mid-1950s. Most of the students came from African and Asian countries, and China attached importance to conveying its own version of socialism, its value system, as well as language to these young people. The scholarships programs were structured and institutionalized with the establishment in 1997 of a regulatory body called the China Scholarship Council, under the control of the Chinese Ministry of Education.[19] The Chinese Government Scholarship Program started to offer fully and partially funded programs to international students. The fully-funded scholarship program is comprised of free tuition, accommodation, medical insurance and a monthly stipend, whereas the partially-funded version covers only tuition fees.[20] Most of the scholarship students continue to come from Africa and Asia. China hopes that future elites of these countries who are exposed to Chinese education, language, culture and society will be sensitive to Chinese viewpoints and interests.[21]

Turkey, unlike the USA, Russia, the UK, the EU and China, is a middle power with limited global ambitions and modest financial resources. Yet, concomitant to the end of the Cold War, Turkey seized an opportunity to raise its profile in the South Caucasian and Central Asian regions thanks to the receding Russian power in these areas following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Accordingly, Turkey pursued an active foreign policy in the early 1990s which also made use of international educational exchanges to permeate these regions culturally. The following section will begin by delving into the major instrument of this cultural expansion strategy, the Great Student Exchange Project; it will then discuss other international educational exchange programs brought forth by successive Turkish governments.

3. Turkey’s Educational Demarche in the Post-Cold War Period: Scholarship Programs

Turkey had not anticipated the sudden and total disintegration of the Soviet Union and therefore was not well-prepared for the altered international environment. However, following initial surprise and confusion, the country got down to work by taking stock of the opportunities extant in the regions that had been freed from the Soviet grip. Azerbaijan and the Central Asian republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan became priority areas for Turkey in the early 1990s, as Turkey and these countries enjoyed some common ethnic, linguistic, historical and cultural ties.

Turkey’s major tool of attraction to lure Azerbaijan and the four Turkic Central Asian states into its orbit became the Great Student Exchange Project, which aimed at improving the educational level in those countries; assisting in meeting qualified manpower needs; fostering a young generation that would be on friendly terms with Turkey; and establishing a permanent ‘brotherhood and friendship bridge’ with the Turkic world.[22] The scholarships provided through the Project included tuition fees, a monthly stipend, one year Turkish language education, accommodation in state dormitories, health insurance, clothing support, books and stationery support, and pass cards for transportation.[23]

Turkey granted 42,318 of these scholarships between 1992 and 2011 as part of the Great Student Exchange Project. The beneficiary countries sent 31,307 students to Turkey during this period. Of these, only 8,914 students ultimately graduated from higher education institutions in Turkey, while 16,138[24] of them eventually lost their scholarships and returned to their home countries. The low graduation rate (28%) could be attributed to various factors, such as the inadequate monthly stipends, the low level of Turkish language proficiency among students, accommodation problems, and the absence of comprehensive orientation programs for foreign students. Nevertheless, some of the participants of the Great Student Exchange Project did ultimately assume high-level political positions in their home countries, from ministers and deputy ministers, to members of parliament, and proved to contribute to the cultivation of friendly ties between their countries and Turkey[25]. This development appeared as a valuable motivating factor for Turkish foreign policy makers to continue with the scholarship program, albeit under a new name and with new content.

The Turkish government launched the Türkiye Scholarships Program in 2012 under the aegis of the Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities (YTB). The Program is aimed at supporting Turkey’s public diplomacy activities by strengthening the country’s political, economic and cultural relations developed in the international area through maintaining close ties with the international students.[26] The international students are expected to act as “country ambassadors” who will build bridges of friendship between Turkey and their countries. The Program also reflects the changes in Turkey’s foreign policy priorities. Compared with its predecessor, this program welcomes more students from African, Middle Eastern and Asian countries in accordance with the JDP governments’ increased interest in these regions.[27]

The Program covers tuition fees, a monthly stipend, one year Turkish language education, accommodation in state dormitories, health insurance and a round-trip flight ticket.[28] The amount of monthly stipends granted to the international students recorded an increase parallel to improvements in Turkey’s financial situation. However, infrastructural problems surrounding dormitories and, more importantly, the overall difficulties encountered by international students while adapting to Turkish-educated programs, persist.[29] There have also been criticisms against the selection criteria. Many candidates have suggested that there be a written exam before the interview process in order to increase the number of accomplished students admitted into the program.

The Türkiye Scholarships Program has introduced two significant novelties that were absent in the Great Student Exchange Project. Firstly, it organizes various academic and social programs for international students to inform them about Turkish history, culture and literature and thus help them to understand Turkish society and build long-term relationships.[30] Second is the foundation of a web site dedicated to graduates of the Program, and the establishment of alumni associations in the sending countries. This alumni network aims to maintain contacts among the scholarship recipients, generate employment opportunities for them, sustain their association with Turkish language and culture, and ensure that they contribute to the development of cordial relations between Turkey and their home countries.[31]

The Mevlana Exchange Program, which was designed by Turkey’s Council of Higher Education (YÖK) in 2011 and came into effect in 2013-2014 academic year, became another international educational exchange program utilized as a soft power instrument for Turkish foreign policy objectives. The Program encompasses the exchange of students and academic staff between Turkish higher education institutions and higher education institutions of other countries through the signing of bilateral protocols.[32] It, in addition to increasing the academic capacity of Turkish higher education institutions and making Turkey a centre of attraction in the area of higher education, anticipates the sharing of Turkey’s historical and cultural heritage.[33] By eliciting recognition among international students and academics, Turkish foreign policy makers aspire for strengthening friendly ties between Turkey and the sending countries.

Students participating in the Program are given a non-refundable scholarship during their studies while academics benefiting from the Program are offered transportation support and monthly allowances. The countries with which Turkey has signed bilateral Mevlana exchange protocols give valuable hints regarding priority areas in Turkish foreign policy. Turkey has signed exchange protocols with six African states (Algeria, Djibouti, Libya, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia), four South Caucasian and Central Asian countries (Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan), four Balkan states (Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Romania), four Middle Eastern states (Iran, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Yemen) two European countries (Malta, the UK) and one Asian country (Malaysia).[34]

The Türkiye Diyanet Foundation (TDV), an organization established to prop up the activities of the Presidency of Religious Affairs of Turkey, also contributes to Turkey’s soft power diffusion by extending scholarships to international students at the undergraduate and graduate levels and opening up higher education institutions in countries where Turkey aims to gain influence. The TDV scholarship covers tuition fees, a monthly stipend, dormitory accommodation, education support, health insurance and a round-trip flight ticket. While the TDV between the early 1990s and mid-2000s preferred setting up higher education institutions in the South Caucasus (Azerbaijan) and Central Asia (Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan), it subsequently has focused on establishing new universities in Africa (Somalia), Asia (Bangladesh, Malaysia) and the Middle East (Palestine), again in accordance with the realignment of Turkey’s foreign policy interests.[35]

In the nearly three decades since the inauguration of the Great Student Exchange Project, Turkey has introduced significant international educational exchange initiatives for enhancing the recognition of its historical background, political values, and socio-cultural features among young populations of the countries with which it aims to advance ties. Furthermore, increases in the number of foreign applications to the Türkiye Scholarships Program, the Mevlana Exchange Program and various scholarship programs of the TDV over these years[36] demonstrates the increasing interest of the sending countries to sustain friendly and thriving relations with Turkey.

It is for sure that Turkey’s leading motive in extending scholarship programs to international students and academics is to create support for its foreign policy goals. Therefore, the final part of the article examines to what extent Turkey’s foreign policy preferences converge with those of the sending countries’ by analysing their voting behaviour in the UNGA.

4. Testing the Contribution of International Educational Exchanges to the Realization of Foreign Policy Goals of Turkey

The study makes use of the UNGA voting records between the years 1985 and 2018 in order to explore the extent of foreign policy convergence between Turkey and those states that benefit from Turkey’s international scholarship programs. Although one state’s upholding of another state’s cause in the UNGA through harmonization of its voting behaviour with that other state’s might be influenced by a diverse set of factors such as the global context, each state’s international standing, definitions of national interest, or domestic considerations; its bilateral relationship with the other state still impinges on its foreign policy decisions. Based on this rationale, this part of the study scrutinizes to what extent the countries with which Turkey has engaged in international educational exchanges have aligned their voting behaviour with Turkey’s regarding foreign policy decisions in the UNGA.

The raw UN voting data draws on the data set prepared by Erik Voeten, Anton Strezhnev and Michael Bailey[37] which includes all the roll-call votes issued in the UNGA between 1946 and 2018. The research focuses on the voting results between 1985 and 2018. The data are divided into three time periods for the purposes of this study: 1985-1991, 1992-2011 and 2012-2018. The period between 1985 and 1991 signifies the Cold War years during which Turkey did not offer any noteworthy international educational exchange programs. The period between 1992 and 2011 denotes the time span which covers the Great Student Exchange Project that was designed in accordance with Turkey’s new foreign policy goals in the wake of the end of the Cold War and the demise of the Soviet Union. The final time period, between 2012 and 2018, corresponds to the era during which the JDP government launched the Türkiye Scholarships Program, Mevlana Exchange Program and expanded the scope of the international scholarship programs of the TDV with renewed interest in Africa and the Middle East. The quantitative UNGA voting affinity analysis utilized in this study is applied separately to these three time periods in order to reveal the changes in the voting cohesion scores throughout the years.

The research compares and contrasts the voting convergence of Turkey with three reference groups. The first group is comprised of Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Argentina, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, China, Colombia, Djibouti, Ecuador, Egypt, Greece, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Libya, Malaysia, Morocco, North Macedonia, Oman, Pakistan, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Tunisia, Ukraine and Yemen. These are the countries whose students and/or academics study and/or give lectures in Turkey within the framework of the Türkiye Scholarships Program, Mevlana Exchange Program and the scholarship programs of TDV.[38]

The second group encompasses Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Comoros, Ethiopia, Gambia, Georgia, Ghana, Guinea, Jordan, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, Montenegro, Serbia, South Korea, Tanzania, Uganda, Vietnam, Zambia and Zimbabwe, countries which benefited from the Türkiye Scholarships Program, but did not send students and/or academics within the framework of the Mevlana Exchange Program or the scholarship programs of TDV. [39]

The third group includes other countries which have not been part of Turkey’s international scholarship programs, namely, Angola, Armenia, Bahrain, Belarus, Benin, Bhutan, Botswana, Brazil, Brunei, Cambodia, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chile, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cuba, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Gabon, Guatemala, Guinea Bissau, Haiti, Honduras, Israel, Ivory Coast, Japan, Kuwait, Laos, Lebanon, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Maldives, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Moldova, Mongolia, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, North Korea, Qatar, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Slovenia, South Africa, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Tajikistan, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Togo, United Arab Emirates, Uruguay, Uzbekistan and Venezuela.

The Agreement Index (AI) method propounded by Simon Hix, Abdul Noury and Gerard Roland to measure party group cohesion in the European Parliament is used to measure the degree of voting convergence between Turkey and these three groups in three separate consecutive time periods mentioned above. The formula of the AI is as follows:

The Yi denotes the number of Yes votes, Ni the number of No votes and Ai the number of Abstain votes expressed by group i for a specific resolution.[40] The AIi figure is ranged between 0 and 1. The closer it is to 1, the higher the voting cohesion of the group. Conversely, scores closer to 0 represent lower voting convergence within the group. The AI is employed in this study as a quantitative UNGA voting affinity analysis tool as it is suitable for tracking changes in cohesiveness for the same group of states over time.[41]

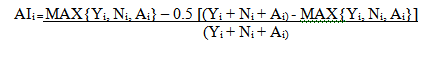

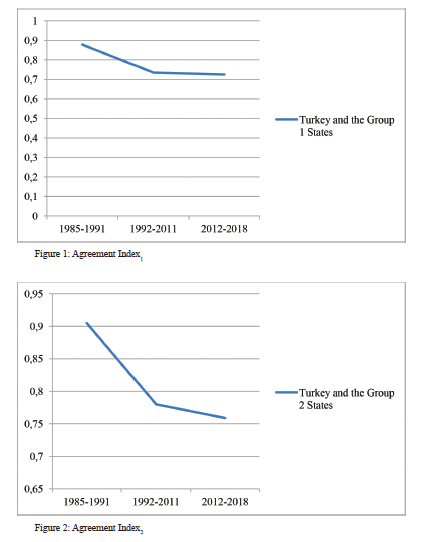

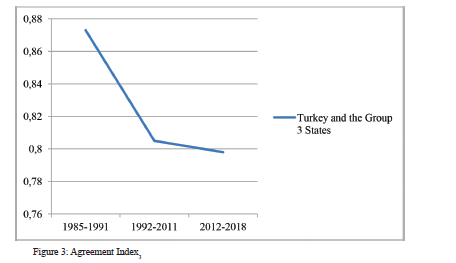

The scores of Agreement Index1, Agreement Index2 and Agreement Index3 as shown in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 reveal interesting results. Figure 1 demonstrates that the voting agreement scores between Turkey and the Group 1 states have declined steadily over the observed years. The trend is the same for Turkey and the states of Group 2 although the overall convergence here is higher than that between Turkey and the Group 1 countries. What is most remarkable for the purposes of this study is that for much of the measured time frame, the data reveal more voting preference alignment between Turkey and the non-sending countries than with the countries which have been exposed to Turkey’s international scholarship programs since the early 1990s.

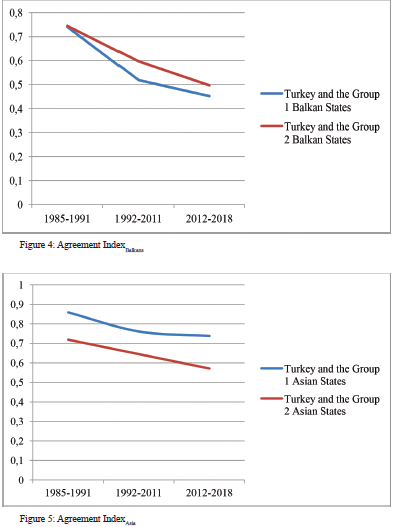

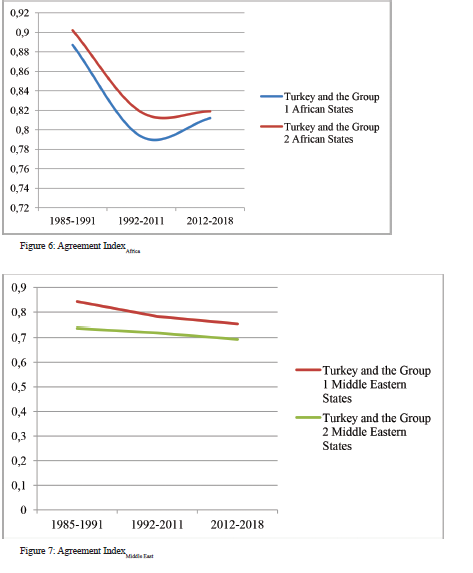

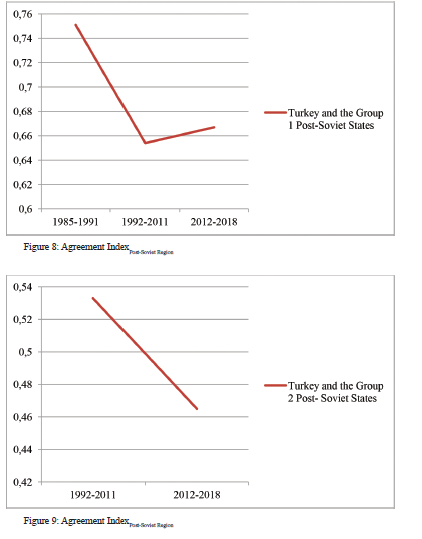

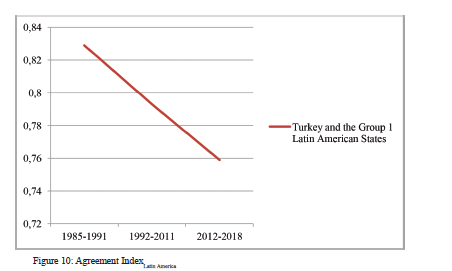

A further in-depth analysis was also employed to examine the extent of voting convergence between Turkey and the Group 1/Group 2 states on a regional basis over the three time periods. In this analysis, the voting agreement scores between Turkey and Group 1 and 2 countries in the Balkan, Asian and Middle Eastern regions declined progressively over the years as indicated by Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 7. In a similar vein, voting convergence between Turkey and the Group 1 states in Latin America also showed a downward tendency since the early 1990s (Figure 10). However, the agreement index scores between Turkey and the Group 1 and 2 states in Africa (Figure 6) depict some upward tendencies. Although the voting cohesion figure between Turkey and the Group 1 African states recorded a 0.094 decrease during the 1992-2011 period, they saw a rise in the consecutive time period. Similarly, the voting agreement score between Turkey and the Group 2 African states registered a 0.084 decrease during the 1992-2011 period but a 0.001 increase in the succeeding time span. It is possible to observe similar trends regarding the voting convergence between Turkey and the Group 1 post-Soviet countries as well. As shown in Figure 8, despite a 0.097 decrease in the voting cohesion figure during the 1992-2011 period, the voting agreement index for this group recorded a 0.013 increase in the 2012-2018 period. The voting convergence between Turkey and the Group 2 post-Soviet countries (Georgia) on the other hand, is on a declining trend as indicated by Figure 9.

The findings disclose that the rise in the number of applications to various Turkish international scholarship programs and the increase in the total number of international students studying in the country since 2012 have not always induced the sending countries to harmonize their voting behaviours in the UNGA with those of Turkey. In fact, with the exception of the cases of Africa and the post-Soviet region, Turkey’s voting preferences in the UNGA seem to diverge progressively from those of the states participating in the international educational exchange programs.

5. Conclusion

The employment of international educational exchanges for foreign policy ends is a long and arduous process. Yet, major powers of the world such as the USA, Russia, the UK, the EU and China have regarded these interactions for a long time as substantial components of their soft power arsenal.

Turkey is a middle power with limited soft power potential compared to these prominent global powers. Still, in the immediate post-Cold War period Turkey came up with a remarkable initiative, the Great Student Exchange Project, to fill the vacuum created in the South Caucasus and Central Asia by the fall of the Soviet Union. While the lack of a well-designed action plan, inadequate financial resources, and cooperation and coordination problems among different state institutions caused the original Project to fall short of expectations, Turkey subsequently managed to rebrand the initiative under a new name and with new content and institutions in 2012. The reconstructed Türkiye Scholarships Program along with the newly introduced Mevlana Exchange Program and the expanded international scholarship programs of the TDV have become significant soft power tools for Turkey to win the hearts and minds of foreign publics through educational diplomacy.

Turkey’s attempt to utilize international educational exchanges for the realization of its foreign policy objectives however, has recorded meagre levels of success. The voting preferences in the UNGA of those countries to whose students and academics Turkey has extended increasing numbers of scholarships since the early 1990s, have, overall, actually become less coherent with Turkey’s voting choices over the years. The only bright spot in the equation is the augmentation of the voting agreement scores between Turkey and cooperating African states and between Turkey and the post-Soviet states (excluding Georgia) in the 2012-2018 period. All in all, although a diverse set of factors might have been influential in the UNGA decision making patterns of the sending countries, sometimes irrelevant to their bilateral ties with Turkey, the fact that the 1992-2018 voting cohesion scores between Turkey and the non-sending countries has been higher than those between Turkey and the sending-countries indicates that international educational exchange programs may not have much positive impact on the realization of Turkey’s foreign policy goals in the post-Cold War period.

Akçalı, Pinar, and Cennet Engin-Demir. “Turkey’s Educational Policies in Central Asia and Caucasia: Perceptions of Policy Makers and Experts.” International Journal of Educational Development 32 (2012): 11–21.

Aras, Bülent, and Zulkarnain Mohammed. “The Turkish Government Scholarship Program as a Soft Power Tool.” Turkish Studies (2018): 1–21.

Budak, Muhammet Musa. “Student Exchange Programs as Public Diplomacy Means and Turkish Examples.” Thesis, Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities, 2012.

Chepurina, Maria. “Higher Education Cooperation in the Toolkit of Russia’s Public Diplomacy.” Rivista di Studi Politici Internazionali 81, no. 1 (2014): 59–72.

Chevening. “Chevening Alumni.” Accessed January 5, 2019. https://www.chevening.org/alumni.

———. “Chevening Scholars.” Accessed January 5, 2019. https://www.chevening.org/scholars.

China Scholarship Council. “About Us”. Accessed January 6, 2019. https://www.cscscholarship.org/about-us.

Coombs, Philip H. The Fourth Dimension of Foreign Policy: Educational and Cultural Affairs. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1964.

Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency. “Scholarship Statistics”. Accessed January 5, 2019. https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/erasmus-plus/library/scholarship-statistics_en.

Ferdinand, Peter. “Rising Powers at the UN: An Analysis of the Voting Behaviour of BRICS in the General Assembly.” Third World Quarterly 35, no. 3 (2014): 376–91.

General Assembly of the United Nations. “Voting Records.” Accessed February 7, 2019. http://www.un.org/en/ga/documents/voting.asp.

Hix, Simon, Abdul Noury, and Gerard Roland. “Power to the Parties: Cohesion and Competition in the European Parliament.” British Journal of Political Science 35 (2005): 209–34.

Kavak, Yüksel, and Gülsün Atanur Baskan. “Educational Policies and Applications of Turkey Towards Turkic Republics and Communities.” Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 20 (2011): 92–103.

Kramer, Paul A. “Is the World Our Campus? International Students and U.S. Global Power in the Long Twentieth Century.” Diplomatic History 33, no. 5 (November 2009): 775–806.

Latief, Rashid, and Lin Lefen. “Analysis of Chinese Government Scholarship for International Students Using Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP)”. Sustainability 10, no. 2112 (2018): 1–13.

Mevzuat Bilgi Sistemi [Legislation Information System]. “Türkiye Bursları Yönetmeliği” [Regulation on Türkiye Scholarships]. Accessed January 19, 2019. http://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/Metin.Aspx?MevzuatKod=7.5.19799&MevzuatIliski=0&sourceXmlSearch=T%C3%BCrkiye%20Burslar%C4%B1%20Y%C3%B6netmeli%C4%9Fi.

Nye, Joseph S. “Soft Power.” Foreign Policy, no. 80 (Autumn 1990): 153–71.

———. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. New York: Public Affairs, 2004.

Oğuzlu, Tarık. “Soft Power in Turkish Foreign Policy.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 61, no. 1 (March 2007): 81–97.

Study in Russia. “Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia”. Accessed January 3, 2019. https://studyinrussia.ru/en/study-in-russia/universities/rudn/students/.

———. “Russian Government Scholarships”. Accessed January 5, 2019. https://studyinrussia.ru/en/study-in-russia/scholarships/.

TDV. “2017 Faaliyet Reporu” [2017 Annual Report]. Accessed January 24, 2019. https://tdvmedia.blob.core.windows.net/tdv/files/Media/Files/raporlar/TDV_2017_FaaliyetRaporu.pdf.

———. “Eğitim-Öğretim Faaliyetleri” [Education-Training Activities]. Accessed January 24, 2019. https://www.tdv.org/tr-TR/site/icerik/egitim-ogretim-faaliyetleri-1077.

Türkiye Mezunları [Türkiye Alumni]. “Hakkımızda” [About Us]. Accessed January 20, 2019. https://www.turkiyemezunlari.gov.tr/hakkinda/.

———. “Mezun Hikayeleri” [Alumni Stories]. Accessed January 17, 2019. https://www.turkiyemezunlari.gov.tr/haberler/mezun-hikayeleri/1/.

Türkiye Scholarships. “Alumni”. Accessed February 06, 2019. https://www.turkiyemezunlari.gov.tr/.

———. “Türkiye Scholarships”. Accessed January 26, 2019. https://www.turkiyeburslari.gov.tr/en/page/about-us/turkiye-scholarships.

———. “What the Scholarship Covers”. Accessed January 19, 2019. https://www.turkiyeburslari.gov.tr/en/page/prospective-students/what-the-scholarship-covers.

U.S. Department of State. “Notable Fulbrighters”. Accessed January 1, 2019. https://eca.state.gov/fulbright/fulbright-alumni/notable-fulbrighters.

Voeten, Erik, Anton Strezhnev, and Michael Bailey. “United Nations General Assembly Voting Data”. Accessed August 28, 2019. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/file.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/LEJUQZ/KKG7SW&version=21.0.

Yang, Rui. “China’s Soft Power Projection in Higher Education.” International Higher Education 46 (2007): 24–25.

Yanık, Lerna K. “The Politics of Educational Exchange: Turkish Education in Eurasia.” Europe-Asia Studies 56, no. 2 (March 2004): 293–307.

Yılmaz, Gözde. “Emulating Erasmus? Turkey’s Mevlana Exchange Program in Higher Education.” Asia Europe Journal (February 2018): 1–15.

YÖK. “Mevlana Değişim Programı” [Mevlana Exchange Program]. Accessed January 22, 2019. http://www.yok.gov.tr/web/uluslararasi-iliskiler/mevlana-degisim-programi.

———. “Mevlana Değişim Programı Kitapçığı” [Mevlana Exchange Program Booklet]. Accessed January 22, 2019. http://www.yok.gov.tr/documents/757816/1380059/Mevlana-Kitapcik-Yeni_08.06.2015_%C4%B0statistiksiz.pdf/13a2eeb0-efbd-4815-b755-56f3f8990d9e.

———. “Yükseköğretimde Uluslararasılaşma Strateji Belgesi 2018-2022” [2018-2022 Strategy Document for Internationalization of Higher Education]. Accessed January 23, 2019. http://www.yok.gov.tr/web/guest/yuksekogretimde-uluslararasilasma-strateji-belgesi-2018-2022.

YTB. “Türkiye Bursları” [Türkiye Scholarships]. Accessed January 20, 2019. https://www.ytb.gov.tr/uluslararasi-ogrenciler/turkiye-burslari.

———. “Türkiye Mezunları Tanzanya’da Buluştu” [Türkiye Graduates Met in Tanzania]. Accessed January 19, 2019. https://www.ytb.gov.tr/haberler/turkiye-mezunlari-tanzanyada-bulustu.