Ziya Öniş and Mustafa Kutlay

Koç University

There has scarcely been a day in the last three years when we have not read depressing headlines in the newspapers about the global economic crisis. The current turmoil, which many experts concur in seeing as the worst jolt to the world economy since the Great Depression, is pushing the parameters of the established system to its limits. One could say that we see, in the short-term measures taken against the crisis at the time, an effective anti-crisis strategy. But ironically, the promptness with which these short-term measures were enacted prevented adequate questioning of the dominant paradigm which had caused the crisis. As a result, the structural problems leading to the crisis were not reduced. Despite the occurrence of the deepest economic crisis to be experienced since the Great Depression, the present economic emergency did not shake the neoclassical economic paradigm as strongly as was needed. A puzzle that this study aims to solve arises here: Why and how has the conventional wisdom survived and reproduced its intellectual hegemony even after the “most devastating economic crisis” since the Great Depression?

1. Introduction

There has scarcely been a day in the last three years when we have not read depressing head- lines in the newspapers about the global economic crisis.[1] The earlier version of this paper presented at Koç University-Kyoto University International Symposium on “Sustainable and Innovative Development”, Koç University, Istanbul (September, 2011). We are grateful to the participants for their valuable comments and suggestions. The current turmoil, which many experts concur in seeing as the worst jolt to the world economy since the Great Depression, is pushing the parameters of the established system to its limits. Orthodox economic theories have been powerless to produce a solution and the solutions which have been devised are not applicable in an international system dominated by nation states. What is more, xenophobic behavior and racist political rhetoric have begun to increase, especially in Europe. In this regard, the outbreaks of violence in Spain, Greece, and the United Kingdom are in the nature of a preface to the social consequences of the economic crisis. The economic meltdown of 2007/08 provided an example of a crisis strategy in which governments in every part of the world intervened vigorously. Led by the American government and the Fed, political and economic decision-makers in many countries intervened with unprecedentedly large rescue packages and were surprisingly well coordinated in the implementation of them. One could say that we see, in the short-term measures taken against the crisis at the time, an effective crisis strategy. Ironically, the promptness with which these short-term measures were en- acted prevented adequate questioning of the dominant paradigm which had caused the crisis. As a result, the structural problems leading to the crisis were not abated.

This article takes this paradox as its point of departure. It asserts that despite the occurrence of the deepest economic crisis to be experienced since the Great Depression, the present economic emergency did not shake the dominant neoliberal economic paradigm as strongly as was expected. The first section of this article discusses the main features of the short-term measures and examines how the structural fault lines are still threatening the world economy. The second section will explain the failure of the latest crisis to upset the neoliberal paradigm sufficiently in terms of three independent but mutually interlinked vari- ables. The conclusion will offer forecasts of the future of neoliberal globalization and global economic governance.

2. The Paradox of Global Financial Crisis: Changes versus Continuities

The immediate global response to the financial meltdown was spectacular in comparison to previous crisis-management experiences.[2]Ziya Öniş and Ali Güven, “The Global Economic Crisis and the Future of Neoliberal Globalization: Rupture versus Continuity”, (GLODEM Working Paper Series 01-10, Center for Globalization and Democratic Gover- nance, Koç University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2010). Governments all around the world, foremost the U.S. government and Federal Reserve, acted in a reasonably swift manner to curb the devastating effects of the financial turbulence. Similarly, international financial institutions, mainly the IMF and World Bank, have arisen from their ashes and taken strong measures to tackle the first global economic catastrophe in the 21st century. Therefore, it appears possible to argue that the immediate responses to the crisis, which we call “proximate changes” and group under the unprecedented bailouts and coordinated interventions on a global scale, are impressive by historical standards.

The first component of the proximate changes is the unprecedented bailouts orga- nized mainly under the auspices of Federal Reserve-Treasury nexus. The Federal Reserve and the Treasury took a relatively proactive stance starting from the outset of financial tur- bulence without hesitating to take unconventional measures. For example, the U.S. govern- ment nationalized the country’s two mortgage giants, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac; took over AIG, the world’s largest insurance company; and, pledged to take up to 700 billion dollars of toxic mortgage-related assets onto its books in October 2008. [3]“When Fortune Frowned,” The Economist, October 9, 2008, 3. Though the huge bailouts helped avoiding financial havoc, the financial contagion spread to the rest of the global economy with unexpected promptness. During the course of 2009, many countries implemented new policy measures to calm down the markets. For instance, the U.S. Con- gress passed a 787 billion dollar economic stimulus package, whereas China undertook a stimulus plan described as having cost around 500 billion dollars. Central banks across the globe followed the Federal Reserve’s demonstrative role in cutting interest rates to almost zero; and its other extraordinary measures, inter alia, buying up more than a trillion dollars in mortgage-backed securities. The severity of the crisis became more obvious when Euro- pean economies plunged into debt mire after Greek authorities declared their inability to put public finances in order in early 2010. The jointly designed IMF-EU rescue package to make nearly 1 trillion dollars available to euro zone states was implemented in early May.

The other crucial aspect of the proximate changes was the transformation of the Bretton Woods’s architecture and global economic governance structures. The IMF, which was a relatively marginalized organization in the pre-crisis context, rose from its ashes im- mediately after the meltdown and became the key actor in coordinated bailouts. Since September 2008, the IMF has extended its approved commitments from SDR600 million in 2007 to SDR79.8 billion in 2010. Several middle-income countries severely hit by the fi- nancial turmoil like Hungary, Greece, and Ireland applied for IMF loans to overcome their balance-of-payments difficulties. Accordingly, the IMF’s lending commitments reached a record level of about 250 billion dollars in March 2011. The IMF’s sister institution, the World Bank, also responded to the financial meltdown swiftly by increasing its lending ca- pacity from 25 billion to more than 58.5 billion dollars over a period of two years. In order to become a more active actor in tackling the crisis, the IMF overhauled its lending practices by phasing out the die-hard conditionality principles and implementing new types of loans such as the Flexible Credit Line and Extended Credit Facility. The second linchpin of inter- national coordination has been the establishment of the G20 as the primary forum of global economic governance. The hitherto G7 was replaced by the G20 in 2008. The recognition of the G20 as the primary mechanism of economic governance sent a strong message in embarking upon the crisis because nearly half of its members are composed of emerging market economies, and the platform represents almost two-thirds of the world population as well as 90 percent of the global economic output. [4]Anthony Payne, “How Many Gs Are There in ‘Global Governance’ After the Crisis? The Perspectives of the ‘Marginal Minority of the World’s States?,” International Affairs 86 (2010). In addition to promoting countercycli- cal expansionary macroeconomic policies, G20 summits are used as effective coordination platforms so as to avoid undesirable and destabilizing beggar-thy-neighbor policies. In the April 2009 London summit, G20 members pledged not to “repeat the historic mistakes of protectionism of previous eras.” [5]See the London G20 summit’s final communiqué: G20, “The Global Plan for Recovery and Reform”, Communiqué of the G20 Summit, London, April 2, 2009, accessed January 20, 2012, <www.g20.org>. The third linchpin of global economic governance has been the establishment of the Financial Stability Board (FSB) in April 2009 with all G20 countries as members. In fact, the FSB evolved from the hitherto insignificant Financial Stability Forum established in 1999, and its mandate has been expanded to a considerable extent so as to empower the board to lead global financial supervision and regulation. In a nutshell, the financial reforms aimed at strengthening the quality and quantity of capital, reducing procyclicality in the financial system, toughening the regulatory framework for financial institutions, and regulating the payments and bonus systems for financial giants.

2. 1. Structural continuities

The initial reform spirit to restructure the international financial architecture, however, has lost momentum in a short time period. Therefore there are still vital structural fault lines in- timidating a sustainable economic recovery in the incoming years. Structural continuities in the post-crisis period can be divided into broad categories: (1) the perpetuation of financial- ization in a still largely under-regulated global economy and (2) the solidification of global imbalances and aggravation of the global economic governance crisis.

One of the most significant structural factors which triggered the global financial cri- sis concerns the phenomenon of “financialization.” Financialization, a term initially coined by Paul Sweezy and Harry Magdoff refers to the “inverted relation between the financial and the real [sectors].” [6]Paul Sweezy and Harry Magdoff, Stagnation and the Financial Explosion (New York: Monthly Review Press:1987). Krippner defines the term “as a pattern of accumulation in which profits accrue primarily through financial channels rather than through trade and commodity production.” [7]Greta Krippner, “The Financialization of the American Economy,”Socio-Economic Review 3 (2005). In a broader sense, financialization depicts “the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economies”. [8]Gerald A. Epstein, “Introduction”, in Financialization and the World Economy, ed. Gerald Epstein, (Massachu- setts: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2005), 3-16. At the heart of it, there is the changing balance and inverted relationship between financial corporations and non-financial firms. The neoliberal globalization project opened up plenty of space for ever-increasing uncontrolled financialization and the rise of a shadow banking system relying on the principle of “originate and distribute.” Accordingly, financial instruments like mortgage-backed securities, credit default swaps, and collateralized debt obligations have become the main profit extraction mechanisms over the last decade. Especially after the early 2000s, the Federal Reserve’s and other leading countries’ accommodative monetary stances, the persistently low real interest rates, credit market distortions, and the sharp financial engineering skills of financial consultants have jointly contributed to the “toxic mix” in financial system.[9]Maurice Obstfeld and Kenneth Rogoff, “Global Imbalances and the Financial Crisis: Products of Common Causes”, (paper prepared for the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Asia Economic Policy Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, October 18-20, 2009), 16. The toxic mix in turn caused the world financial markets grow far beyond its means. As Crotty points out, the financialization of the U.S. economy created mountains of debt with huge risks accumulated in the system:[10]James Crotty, “Structural Causes of the Global Financial Crisis: A Critical Assessment of the ‘New Financial Architecture’”, Cambridge Journal of Economics 33 (2009): 575-576.

The value of all financial assets in the US grew from four times GDP in 1980 to ten times GDP in 2007. In 1981 the household debt was 48 per- cent of GDP, while in 2007 it was 100 per cent. Private sector debt was 123 percent GDP in 1981 and 290 percent by late 2008. The financial sector has been in a leveraging frenzy: Its debt rose from 22 percent of GDP in 1981 to 117 percent in late 2008. The share of corporate profits generated in the financial sector rose from 10 percent in the early 1980s to 40 percent in 2006, while its share of the stock market’s value grew from 6 percent to 23 per cent.

The uncontrolled neoliberal liberalization policies were accompanied by overly lax, fragmented, and ineffective regulatory mechanisms and the globally integrated financial markets were not supervised by regulatory bodies of a global scale. Indeed, during the era that the neoliberal doctrine deepened its hegemony, a fundamental flaw dominated the politi- cal economy of global finance, namely deeply integrated and sophisticated financial markets “managed” by shallow regulatory institutions, which are domestic in scope and neoliberal in philosophy. As a result, global financial integration has been promoted without paying adequate attention to prudential mechanisms on a global scale. The “paradigm dependence” embedded in the neoliberal doctrine still remains as the basic systemic fault line even after the crisis, because the post-2008 discussions on financial regulation do not adequately con- centrate on the deep-seated phenomena of financialization and under-regulation. On the con- trary, the lackluster solution proposals fall short of digging deeper on the structural causes of the recent debacle. The ambitious statements of G20 leaders during the initial phases of the financial crisis were gradually replaced by orthodox rhetoric and perennial tug-of-wars at international summits turned into business as usual.

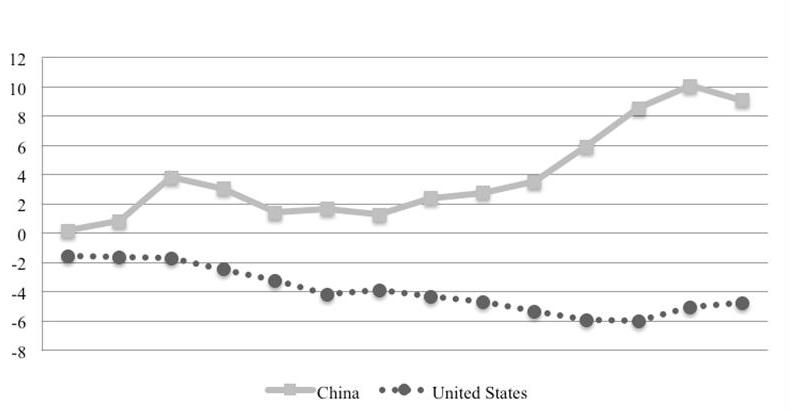

The other structural component of the recent global financial crisis is the system- ic deficits/surpluses, the oft-mentioned global imbalances, and the legitimacy crisis of the global governance mechanisms. During the 2000s, trade and financial flows expanded spec- tacularly, economic growth was kept extraordinarily robust and inflation and interest rates were caged at tolerable levels. The seemingly favorable global economic conditions, how- ever, were impeded by two major developments that distorted global equilibrium. The first development was the asymmetric growth of current account deficits among countries. In this regard, the tug-of-war between the world’s biggest economies, the U.S. and China, deserves major emphasis. Over the last decade, U.S. economic growth has increasingly depended on current account deficit, which is mainly financed through the astonishingly high savings of emerging countries, mainly lead by China. As we demonstrate in the following figure, in this period, the U.S. current account deficit and China’s current account surplus have become the two faces of the same coin.

The asymmetric growth of current account balances was in fact the result of un- sustainable growth models pursued by U.S. and Chinese policy-makers. The consumption- led growth deteriorated saving rates in the U.S., whereas the Chinese gradually increased their savings as a result of their export-oriented and consumption-discouraging domestic economic policies. According to one perspective dominant in U.S. policy circles, “the high savings of China, oil exporters and other surplus countries depressed global interest rates, leading investors to scramble for yield and under-price risk.”[11]Maurice Obstfeld and Kenneth Rogoff, “Global Imbalances and the Financial Crisis: Products of Common Causes”, 2. The “global saving glut”, in Bernanke’s jargon, has pushed the interest rates down and encouraged investors to borrow at cheaper rates but invest in riskier assets. [12] Krishna Guha, “Paulson Says Crisis Sown by Imbalance,”Financial Times, January 1, 2009; and Ben S. Bernanke, “Financial Reform to Address Systemic Risk,” (speech delivered at the Council on Foreign Relations, Washington D.C., March 10, 2009) Not surprisingly, the U.S. Treasury is one of the primary actors in this scramble. Though the exact linkages between global imbalances and global economic crisis remain to be clarified, what is quite obvious is that the over- consumption by Western countries led by the U.S. and over-saving by Pacific states led by China proved unsustainable and nothing meaningful has been accomplished to address these global imbalances in the post-2008 era. On the contrary, the diverging opinions between Chinese and American policy-makers in terms of appropriate exchange-rate policies and a reorientation of Chinese growth toward domestic demand have so far dominated interna- tional summits. Therefore, the improvement of a coordinated response to large-scale global imbalances remains an urgent necessity because as Obstfeld and Rogoff succinctly put it, in the incoming years, “the Asian model of export growth becomes more problematic if the U.S. is no longer the world’s borrower of last resort.” [13]Maurice Obstfeld and Kenneth Rogoff, “Global Imbalances and the Financial Crisis: Products of Common Causes”, 35.

Figure 1: Current account surplus/deficid, China vs. U.S. (% of GDP, 1996-2010)

Source: IMF

Second, the global economic growth was fuelled in an unsustainable manner due to the increasing debt leverage of advanced economies. The mounting levels of debt in many countries in this period, especially in developed Western states, significantly contributed to global imbalances. The global economic meltdown and the accompanying government bailouts paradoxically led to further deterioration of global macroeconomic balances. In this context, the policy responses to the recent crisis did not alleviate the problem of global asymmetries; on the contrary, the asymmetric debt burden turned into a new risk factor that opened up new fault lines because the aggregate debt of advanced economies is project to rise from 18.1 trillion dollars in 2007 to 29.5 trillion dollars in 2011, and is expected to increase to 41. 3 trillion dollars in 2016. The same numbers for emerging market economies will not be more than 3.8 trillion dollars, 4.9 trillion dollars, and 6.7 trillion dollars, respectively. In other words, the ratio of aggregate debt to aggregate GDP for advanced economies will rise from 46 percent in 2007 to 70 percent in 2011 and further to 80 percent in 2016.

Table 1- Asymmetric Debt Burden of G20 Countries (Gross Debt/GDP)

| Country/Year | 2007 | 2011 | 2016 |

|

Developed Countries |

|||

|

Australia |

9.5 |

24.1 |

20.6 |

| Canada | 66.5 | 82.7 | 72.6 |

| France | 63.9 | 84.8 | 84.1 |

| Germany | 64.9 | 82.3 | 71.9 |

| Italy | 103.6 | 120.6 | 118.0 |

| Japan | 187.7 | 232.2 | 250.5 |

| Korea | 29.7 | 28.8 | 19.8 |

| UK | 43.9 | 82.9 | 81.3 |

| US | 62.2 | 98.3 | 111.9 |

| Developing Countries | |||

| Argentina | 67.7 | 40.7 | 31.4 |

| Brazil | 65.2 | 65.6 | 58.6 |

| China | 19.6 | 16.5 | 9.7 |

| India | 75.8 | 66.2 | 61.8 |

| Indonesia | 36.9 | 25.4 | 19.9 |

| Mexico | 37.8 | 42.4 | 41.4 |

| Russia | 8.5 | 8.5 | 15.9 |

| Saudi Arabia | 18.5 | 8.3 | 3.7 |

| South Africa | 28.3 | 40.5 | 38.7 |

| Turkey | 39.4 | 39.4 | 34.0 |

Source: Brookings and Financial Times

The corresponding ratios for emerging market economies are just 28 percent, 26 percent, and 21 percent, respectively. [14]Eswar Prasad and Mengjie Ding, “Debt Burden in Advanced Economies Now a Global Threat,”Financial Times, July 31, 2011.

The deepening global imbalances in terms of systemic deficits/surpluses and the asymmetric debt burden dispersed throughout the world economy underpinned the legiti- macy crisis of global economic governance as well. The established international financial institutions have legitimacy problems due to the asymmetric representation mechanisms. These financial institutions like the IMF and World Bank have taken their roots from the Bretton Woods architecture and represent the perspective of U.S. hegemony in terms of in- stitutional mindset and voting-principles. Although much water has passed under the bridge over the last two decades and the global economic ground has shifted dramatically, the new- ly rising BRICS is still being underrepresented in these organizations. The recent amend- ments of the IMF and World Bank put forward after the Pittsburgh G20 summit in 2009 are nothing more than mere lip service paid by established powers in order to mitigate the voices pointing out governance asymmetries in the global economy. Given the growing importance of emerging markets’ contribution to world economic output, trade, and finance, these new power blocs demand a stronger political voice at international platforms so as to stand on an equal and just footing with their Western counterparts. Their demands have so far fallen into the deaf ears of core capitalist economies. Yet, global governance is a double-edged sword for emerging powers as well because power sharing also means accepting new responsibili- ties in terms of burden sharing. Understandably proud of their strategic capitalist model, the newly rising powers have little incentive to change their policy preferences so that they are “expected to continue playing hard ball in global trade and environmental talks.” [15]Ziya Öniş and Ali Güven, “The Global Economic Crisis and the Future of Neoliberal Globalization: Rupture versus Continuity,” 479. For ex-ample, BRICS does not show an eager stance to take more responsibility in improving the global coordination problems in economic, political, and environmental realms and drags its foot in reducing surpluses to make it easier for Western economies to diminish their huge deficits. Therefore, the governance of the global economy still skids around in a cul-de-sac in the post-2008 process, thereby representing more of the same vis-à-vis the pre-crisis period.

3. Explaining the Persistence of Structural Continuities

Having taken the “proximate changes” and “structural continuities” into consideration si- multaneously, the global financial crisis makes us face a peculiar paradox: The unprecedent- ed government bailouts and coordinated public interventions created a sense of “difference” in terms of dealing with the crisis effectively. The necessary steps were taken quickly to miti- gate the proximate causes of the global turmoil. However, proximate changes overshadowed the underlying structural problems of global economic governance and made it practically impossible to strongly tackle the deep-rooted causes of the recent economic fluctuation. It is hardly possible to argue that the crisis opened up an adequate epistemological space to discuss the material and intellectual fundamentals of a possible “paradigm shift.” The main characteristics of the post-crisis discussions, consequently, still revolve around the orthodox paradigm. In fact, the post-2008 discussions resemble “paradigm dependence” more than a “paradigm shift.” A puzzlement that this study aims to solve arises here: Why and how has the conventional wisdom survived and reproduced its intellectual hegemony even after the “most devastating economic crisis” since the Great Depression? The rest of this paper concentrates on three main reasons to explain this “paradigm dependence” by scrutinizing these points in detail.

3.1.‘Not widespread, deep, and long enough’

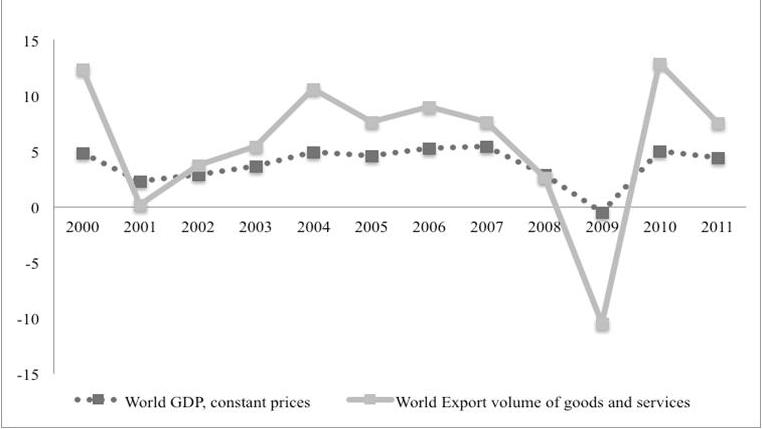

One of the immediate reasons for the persistence of structural problems is directly related to the intensity level of the recent global economic crisis. This becomes a more palpable fact especially in comparison to the Great Depression of 1929. If we borrow from Kindleberger, the recent global crisis is not as “widespread, deep, and long” as the Great Depression.[16]Charles P. Kindleberger, The World in Depression, 1929-1939 (London: University of California Press: 1973). First of all, the world economy had shrunk in 2009 by merely less than 1 percent. The total export volume declined 10.5 percent, yet it quickly recovered in a year’s time.

Figure 2: The “Depth” of Global Financial Crisis (World, % change)

Source: IMF

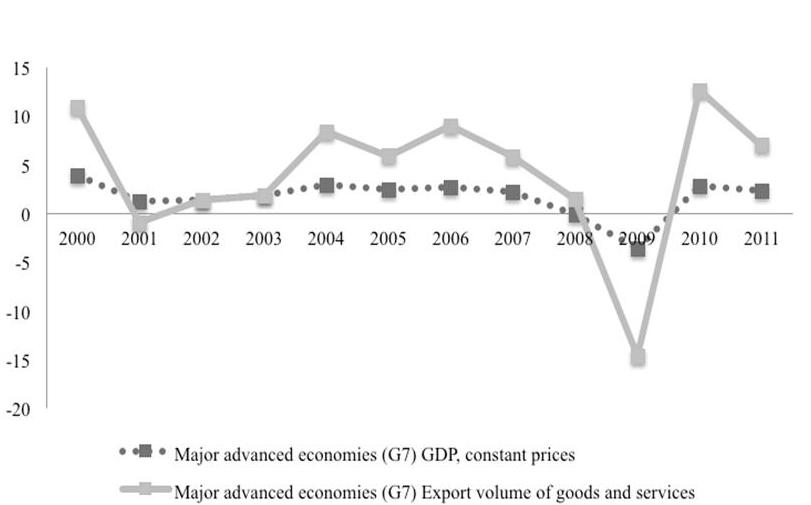

The impact of the global crisis is more profound on developed economies in the sense that the contraction in G7 economies is more than 3.5 percent with an accompanying export decline of almost 15 percent. Nevertheless, the advanced economies also quickly recovered in 2010 and the prospects of growth turned positive.

The intensity of the shocks and the depth of the crisis is the key independent variable in attracting people’s attention to the structural problems rather than satisfied with shal- low proximate changes. In the Great Depression of 1929, it was the depth of the economic shock that enabled people to overcome the interregnum threshold and search for alterna- tives to the existing mechanisms.[17]Eric Helleiner, “A Bretton Woods Moment? The 2007-2008 Crisis and the Future of Global Finance,” Inter- national Affairs 86 (2010). In three years’ time, up to Roosevelt’s declaration of a four-day bank holiday in March 1933, thousands of banks failed, destructive deflation set in, and output plunged. In the Great Depression, the average length of time over which output fell was 4.1 years and countries took an average of ten years to increase their output back to pre-crisis levels. The rate of unemployment in the U.S. rose from 3.2 percent to 24.9 percent.[18]Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press: 2009), 233-237. The protectionist tendencies intensified remarkably as a result of which President Hoover approved the Hawley-Smoot Tariff that sharply raised duties on a large variety of items imported into the U.S. in the early 1930s.[19]Gene Smiley, Rethinking The Great Depression (Chicago: Ivan Dee: 2002), 13-14. In comparative perspective, however, the impact of the recent economic crisis is not as “widespread, deep, and long” as the Great Depression. One of the reasons for this puzzlement is the proactive interventionist policies and huge bailout packages implemented by national authorities. The Federal Reserve and Treasury intervened in the markets at an early time when it was not even clear whether the economy had plunged into a recession. The “learning effect” of the Great Depression for the U.S. authorities is striking. Moreover, the coordinated response of central banks all around the world avoided an acute liquidity crisis in the financial system. Ironically, the proximate measures taken immediately after the crisis created a psychological atmosphere to overlook the structural problems. The swift yet unsustainable economic recovery in this sense alleviated the legitimacy crisis of the existing economic system without fixing the root causes of the global economic turmoil.[20]It is important to underline that “swift recovery” is different than “sustainable ” The recovery after the recent crisis is swift but proved unsustainable. Therefore a possible “double dip” in the following months may change the entire story.

Figure 3: The “Depth” of Global Financial Crisis (G7 economies, % change)

Source: IMF

3.2. The rigidity of mainstream ideas

The other important factor that underpins the structural continuities is the rigidity of main- stream ideas, which has developed an unshakable belief in the self-adjusting mechanisms of financial markets. Having taken its roots from neoclassical economics, orthodox ideas relied on the efficient market hypothesis that argues that the prices of traded goods reflect all the information available. In the financial realm, the “perfectly competitive markets”[21]Paul Krugman, “How Did Economists Get It So Wrong?,” The New York Times, September 9, 2009. assumption is taken to its extreme ideational forms. The financial markets are regarded as highly com- petitive places in which information is symmetric/perfect and arbitrage opportunities are rare.[22]Sheila Dow, “Mainstream Methodology, Financial Markets, and Global Political Economy”, Contributions to Political Economy, 27 (2008). Rational choice theory, efficient market hypothesis, and quantitative research meth- odology reinforced one another in the way that an intellectual consensus is established in the neoliberal era.[23]Henry Farrell and Martha Finnemore, “Ontology, Methodology, and Causation in the American School of International Political Economy,” Review of International Political Economy 16 (2009). The ideational contours of mainstream economics are framed in such a way that two points have become the standard norms in economics courses. First, dominant economic models heavily relied on individual agents as completely rational and socially isolated actors that have no capacity to change their “preferences” in a socially interactive manner. Second, the markets were regarded as perfectly competitive places in which agents acted as “price-takers” devoid of all kinds of information asymmetries problems.[24]24 Walter O. Ötsch, and J. Kapeller,”Perpetuating the Failure: Economic Education and the Current Crisis,” Journal of Social Science Education 9 (2010). The testable hypothesis and empirical analysis have turned out to be the standard approach of main- stream macroeconomic analysis over the years. Since formal modeling dominated the subject field, mainstream studies have concentrated on sophisticated, yet particularistic analysis of the events, as a result of which the social whole is left behind the scope of inquiry. The dominant approach to the study of finance, in this regard, has become more and more particularistic and despite its sophistication and methodological rigor mainstream economics failed to appreciate the risky transformation of financial markets during the neoliberal era. It is important to underline at this point that quantitative studies are quite useful in improving theory-testing in political economy, and do not pose any problem by themselves. The problem occurs when they pave the way for methodological blindness by ignoring the holistic approaches on grounds of finding them too wide-ranging and vague to be tested. The conventional wisdom of finance, unfortunately, has suffered from this kind of methodological bias at least due to two main reasons. First, in terms of financialization and global financial crisis, mainstream political economy reasoning did not ask the relevant questions due to the methodological constraint; therefore, “[it] leaves too much out [and] in its preference for reductionism, risks limiting our vision to individual trees”.[25]Benjamin J. Cohen, International Political Economy: An Intellectual History (Princeton: Princeton Univer- sity Press: 2008), 141. Putting the issue another way, the very methodology has determined the questions to be asked in the subject field. Not surprisingly, the relevant big questions on financialization and global financial crises were not asked by the orthodox perspectives.[26]Robert Keohane, “The Old IPE and the New,” Review of International Political Economy 16 (2009). Instead, the technicalities of the financial instruments such as pricing derivatives, futures, and forwards dominated the research agenda without recognizing their destructive potential as “war machines”.[27]İsmail Ertürk, Adam Leaver, and Karel Williams, “Hedge Funds as ‘War Machine’: Making the Positions Work,” New Political Economy 15 (2010). Wade felicitously captures this problematique:[28]Robert Wade, “Beware of What You Wish For: Lessons for International Political Economy from the Transformation of Economics,” Review of International Political Economy 16 (2009):117.

[Orthodox analysis] should be alert to the dangers of elevating formalization and quantification as primary criteria for the selection of research subjects. When the existence of a ‘data set’ suitable for rigor- ous analysis becomes an almost necessary condition for selection, big questions and propositions not amenable to ‘rigor’ get marginalized… It is like unraveling a colorful tapestry in order to end up with piles of different color wools. It prompts the question, ‘I see your bridle, but where is your horse?

Second, as Krugman underscores, the neoclassical approach lacks both a temporal and spatial dimension and assumes that economic activities take place in an abstract universe devoid of history and geography.[29]Paul Krugman, Geography and Trade (Massachusetts:The MIT Press: 1993). Having relied on neoclassical methodology, conventional wisdom has become more prone to study finance within the context of a static taken-for-granted approach and ignored the historical evolution of the financial markets over the last three decades. The methodological individualism, as a consequence, has not enabled pundits to develop a comprehensive approach in discovering vital interaction between the state and financial markets on the one hand, and its system-wide repercussions on the other. The “dominance of technique over substance,” in Hodgson’s terms,[30]Geoffrey M. Hodgson, “The Great Crash of 2008 and the Reform of Economics,” Cambridge Journal of Economics 33 (2009): 1209 has prioritized the tools of analysis instead of the historical, institutional, and ideational context in which research questions about economic crises arise.

The mainstream economic reasoning, consequently, left no room for the possibility of financial bubbles and irrational market exuberance. In the case of bubbles and short-term disequilibria, state intervention is dismissed in favor of self-attributed market dynamics as the most efficient adjustment mechanisms.[31]Robert H. Wade, “Financial Regime Change,” New Left Review 53 (2008):6 Hence, the question of financialization as a structural phenomenon and its broader socio-economic repercussions was never taken into the mainstream political economists’ research agenda. Even though four years have passed since the beginning of the global financial crisis, it is still too difficult for conventional per- spectives to meet this burning reality.

3.3.The power of the Wall Street lobby

The ideational rigidity by itself, however, is not capable of explaining the persistence of structural continuities. The vested interests and institutional embeddedness of the financial lobby also play their role in the regulatory tug-of-war. From this point of view, rather than appropriately discussing proposals for a solution, the point is to thrash out the possibility of putting alternatives into practice due to the naked fact that it is truly a herculean task to circumvent the incumbent anti-reform lobby clustered around Wall Street operators. The anti-reformist Wall Street lobby’s intense power stems from three interrelated yet separate sources, which are material resources and lobbying power, links between public authorities and financial actors, and intellectual superiority.[32]Andrew Baker, “Restraining Regulatory Capture? Anglo-America, Crisis Politics and Trajectories of Change in Global Financial Governance,” International Affair 86 (2010). In terms of material resources and lobbying power, the thirty-year long neoliberal policies have tilted the power balance decisively in favor of the financial elites. The financial deregulation of the 1980s that scrapped capital controls opened up a large room for the investment banks to expand their trading capabilities and accrue huge amounts of profits. Consequently, proprietary trading in financial assets on their behalf has become the central activity for investment banks. By the end of 1990s, trading income was a third bigger than income from commissions for trading on behalf of others, and five investment banks with more than 4 trillion dollars worth of assets had become the key players in the New Wall Street System.[33]John Gapper, “After 73 Years: The Last Gasp of the Broker-Dealer,” Financial Times, September 15, 2008; and Peter Gowan, “Crisis in the Heartland: Consequences of the New Wall Street System,” New Left Review 55 (2009): 8-10. Similarly, the after-tax profits of financial companies jumped from below 5 percent of total corporate profits in 1982 to 41 percent in 2007.[34]Martin Wolf, “Why it is so Hard to Keep the Financial Sector Caged,” Financial Times, February 5, 2008. The hitherto secondarily important financial firms have turned out to be the so-called “masters of the universe.” In this conjuncture, Charlie Wilson’s famous gaffe of the 1950s, “What’s good for General Motors is good for the country,” was gradually replaced by the motto of “What is good for Wall Street is ‘all that matters”.[35]David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press: 2005), 33 Since financial elites have become the foremost benefactors of neoliberal globalization and an unregulated financial system, they have gained the upper hand by sustaining the status quo via intense campaign financing and lobbying activities. The financial sector spent 1.7 billion dollars in federal election campaigns and 3.4 billion dollars to lobby federal officials between 1998 and 2008.[36]Crotty, “Structural Causes of the Global Financial Crisis: A Critical Assessment of the ‘New Financial Architecture,’” 577. Therefore, every bold reform proposal today hits the anti-regulatory coalition clustered around key posts in “Wall Street-Washington corridors”.[37]Baker, “Restraining Regulatory Capture? Anglo-America, Crisis Politics and Trajectories of Change in Global Financial Governance,” 652.One striking example is the January 2010 reform proposal, the oft-mentioned “Volcker Rule” by which U.S. President Barack Obama and his economic team called “for new restrictions on the size and scope of banks and other financial institutions to rein in excessive risk taking and to protect taxpayers.”[38]“President Obama Calls for New Restrictions on Size and Scope of Financial Institutions to Rein in Excesses

and Protect Taxpayers,” The White House, January 21, 2010, accessed <http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-pressoffice/

president-obama-calls-new-restrictions-size-and-scope-financial-institutions-rein-e> Obama’s ambitious assault paved the way for the next round of lobby wars in the U.S., and in a short time period, it became apparent that implementing bold reforms by way of circumventing the Wall Street lobby is not child’s play.

The second source of Wall Street lobby’s power stems from links between public authorities and financial actors. Over the last thirty years, the combined effects of prevailing ideas and intense lobbying activities resulted in the “extraordinary harmony between Wall Street operators and Washington regulators”.[39]Gowan, “Crisis in the Heartland: Consequences of the New Wall Street System,” 20. For example, many Goldman Sachs alumni like Robert Rubin, Henry Paulson, and William C. Dudley have taken up key posts at the Treasury and the Federal Reserve. The close connections between public authorities and private financial firms created a “regulatory capture” in the sense that “bureaucrats, regulators and politicians cease to serve some notion of a wider collective public interest and begin to systematically favor vested interests, usually the very interests they were supposed to regulate and restrain for the wider public interest”.[40]Baker, “Restraining Regulatory Capture? Anglo-America, Crisis Politics and Trajectories of Change in Global Financial Governance,” 648. Due to the overlapping interests and parallel mindsets between public authorities and financial actors, the decisions beneficial for a small cluster of financial firms are assumed to be beneficial for the entire economy. The international organizations, in this period, have become the staunch supporters of abolishing all kind of barriers to capital flows. For example, the International Monetary Fund amended its Articles of Agreement “to make the promotion of capital account liberalization a specific purpose of the IMF” in May 1997.[41]Jonathan Kirshner, “The Study of Money,” World Politics 52 (2000): 433. At the state level, the Glass-Steagall Act, which sepa- rated investment banks and depository banks in the U.S., was formally repealed in 1999. By doing so, financial globalization was boosted by facilitating the growth of a shadow bank- ing system of hedge funds, mortgage funds, and other similar special investment vehicles.[42]Joseph E. Stiglitz, “Regulation and Failure”, in New Perspectives on Regulation, ed. D. Moss, and J. Cisternino (Cambridge: The Tobin Project, Inc.: 2009). Other leaders of developed countries joined the U.S. in liberalizing the institutional designs of their financial markets. British Labor Party leaders, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, sub- sequently declared their strategy to create “not only light but also limited regulation” in the UK financial system.[43]Wade, “Financial Regime Change,”12.

The third source of the Wall Street lobby’s power stems from the attitudes of ortho- dox scholars. Many influential financial political economists bandwagon the “Wall Street-Treasury complex” partially because of the paradigm dependence and lucrative consultancy posts available.[44]Hodgson, “The Great Crash of 2008 and the Reform of Economics,” 1214. The increasing gravity of business schools, in this period, took advantage of the existing material networks. Under such circumstances, most scholars in conventional wisdom did refrain from spoiling the party. In The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Keynes argues that “speculators may do no harm as bubbles on a steady stream of enterprise.[45]John M. Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (London: St. Martin’s Press: 1960),159. But the position is serious when enterprise becomes the bubble on a whirlpool of speculation. When the capital development of a country becomes a by-product of the activities of a casino, the job is likely to be ill-done.” Though the evidence suggests that the entire world economy tilted to become a by-product of the activities of a casino, regulatory institutions and orthodox scholars insist on turning a blind eye partially because of their vested interests.[46]Ben Fine, “Neo-liberalism in Retrospect- It’s Financialization, Stupid,” (paper prepared for Conference on

Developmental Politics in the Neoliberal Era and Beyond, Center for Social Sciences, Seoul National University, 22-24 October 2009). Under these circumstances, the structural calamities of the recent financial crisis are not discussed adequately among intellectual platforms. As a result, the Wall Street lobby successfully created an anti-reformist historical bloc by way of linking material and lobbying resources, public-private partnership, and ideational consensus together. Not surprisingly, the existing power bloc insists on saving the day by just implementing light-touch measures.

4. Revisiting the Paradox of Global Financial Crisis

This article has examined the 2007-08 global economic turmoil, a crisis which many experts agree to be the biggest economic crisis we have experienced since the Great Depression. It stresses that the short-term measures and global interventions used to counter the crisis were integrated and concerted in a way which had not been the case in previous crises. However, this study proceeds by establishing the fact that the policy measures taken were short term in orientation, and that in the fight against the structural elements which contributed to the crisis of neoliberal globalization, the reforms agreed upon as necessary at international platforms, including the G20, lacked the courage and determination that was needed. We aim to resolve the paradox that the reforms were also short term, incremental, and piecemeal, despite the depth of the crisis and offer an explanation relying on three independent variables which were interconnected. This account subjects the structural problems of neoliberal globalization to thorough criticism and argues that attempts to create a political base to counter the effects of the crisis, as happened after the Great Depression, were insufficient because (1) compared to the Great Depression, the recent crisis has not been sufficiently “long, wide- spread, and deep.”Instead, in the post-crisis process, the risk of recession in the form of a “creeping crisis” has established itself as the basic characteristic of the global economic system; (2) the recent crisis has come up against the sturdy walls of the dominant economic paradigm, but it has not been able to open an intellectual breach in the walls of neoclassical economic paradigm so as to create breathing space for alternative paradigms. Finally, (3) well-established power blocs within the system, which it would be appropriate to call the Wall Street lobby, have opposed comprehensive structural reforms with all their might and have been largely successful in their efforts.

What have we learned from the first global crisis of the 21st century and what sort of morals for the future of neoliberal globalization can be extracted from these lessons? Three points which arise from this article need to be stressed. First, the global economic crisis demonstrates the importance of preserving the balance between industry and finance in the globalizing world. Financial growth occurring independent of industrial production and not keeping step with real economic growth, i.e., “financialization,” has turned out to be the Achilles’ heel of economic globalization in a most striking fashion. Excessive dependence on finance has shown a face in the central countries of the capitalist system which creates an instability that stretches far beyond the prevailing economic theories that capital would be directed from unproductive channels into more productive ones. Consequently, in order to achieve sustainable economic growth and a non-damaging form of globalization, there must be top priority efforts at every economic platform, notably the G20, to reverse the process of financialization. Second, it is now clear that the efforts of a single hegemonic power or even of a single bloc are insufficient to achieve sustainable globalization. The newly rising economic forces in the world, notably China, should play a more active role in producing better-balanced sustainable economic growth—they need to roll up their sleeves. Because the two key actors linked in the global economic crisis and with structural imbalances such as an extreme surplus or deficit of savings, are the U.S. and China. As a result, neither the

U.S. by itself nor the developed Western economies now possess the ability to effectively dispose of the global imbalances by themselves. This brings us to the third and most im- portant point relating to the governance of the global economic system: the limits upon global governance. There is no doubt that the recent upsets have had a global aspect and that the structural reforms needed to cope with them also have a global characteristic. Thus the G20 has become an important platform because it offers a suitable base where developing countries can present their contributions. Yet short-term measures being invoked to cope with the crisis and the discussions held so far regarding reforms ironically demonstrate how very different the ideas held by G20 members are from one another when it comes to global governance and the future of the global economic system. Even among Western economies, there are serious differences regarding the form the financial system should take, but when countries like China, India, Russia, Brazil, and Turkey are added to the equation, then the differences in ideas and policies may become insurmountable. What is more, just when the world economy is experiencing a desperate need for global coordination, it has been found that the power of nation states has grown well beyond what it was in the period before the crisis. This is because at a time when rescue packages are paid out of the taxes collected from the people of nation states, leaders cannot leave the decision-making process in the hands of technocrats who do not have to worry about being re-elected or in those of politi- cians from other countries. Therefore, we are at a crossroads and facing challenging hurdles in establishing the stability of the world economy. As Gramsci put it, “the old order is dying and the new cannot be born.” When the constraints above are borne in mind, one must express concern over whether or not the birth, if it does indeed happen, will be very painful.

“When Fortune Frowned.” The Economist, October 9, 2008.

Baker, Andrew. “Restraining Regulatory Capture? Anglo-America, Crisis Politics and Trajectories of Change in Global Financial Governance.”International Affairs 86 (2010): 647-663.

Bernanke, Ben. “Financial Reform to Address Systemic Risk.” Speech delivered at the Council on Foreign Relations, Washington D.C., March 10, 2009.

Cohen, B. International Political Economy: An Intellectual History. Princeton: Princeton University Press: 2008.

Crotty, James. “Structural Causes of the Global Financial Crisis: A Critical Assessment of the ‘New Financial Architecture’.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 33 (2009): 563-580.

Dow, Sheila. “Mainstream Methodology, Financial Markets, and Global Political Eco- nomy. ” Contributions to Political Economy 27 (2008): 13-29.

Epstein, Gerald A.. “Introduction. ” In Financialization and the World Economy, edited by Gerald Epstein, 3-16. Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2005.

Ertürk, İsmail, Adam Leaver, and Karel Williams. “Hedge Funds as ‘War Machine’: Making the Positions Work.” New Political Economy 15 (2010): 9-28.

Farrell, Henry, and Martha Finnemore. “Ontology, Methodology, and Causation in the American School of International Political Economy.” Review of International Political Economy 16 (2009): 58-71.

Fine, Ben. “Neo-liberalism in Retrospect - It’s Financialization, Stupid.” Paper prepared for Conference on Developmental Politics in the Neoliberal Era and Beyond, Center for Social Sciences, Seoul National University, 22-24 October 2009.

Gapper, John. “After 73 Years: The Last Gasp of the Broker-Dealer. ”Financial Times, September 15, 2008.

Gowan, Peter. “Crisis in the Heartland: Consequences of the New Wall Street System.” New Left Review 55 (2009): 5-29.

Guha, Krishna. “Paulson Says Crisis Sown by Imbalance.”Financial Times, January 1, 2009.

Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 2005. Helleiner, Eric. “A Bretton Woods Moment? The 2007-2008 Crisis and the Future of Global Finance.” International Affairs 86 (2010): 619-636.

Hodgson, Geoffrey M.. “The Great Crash of 2008 and the Reform of Economics. ”Cambridge Journal of Economics 33 (2009): 1205-1221.

Keohane, R. “The Old IPE and the New.” Review of International Political Economy 16 (2009): 34-46.

Keynes, John. The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. London: St. Martin’s Press: 1960.

Kindleberger, Charles P. The World in Depression, 1929-1939. London: University of California Press: 1973.

Kirshner, Jonathan. “The Study of Money.” World Politics 52 (2000): 407-436.

Krippner, Greta. “The Financialization of the American Economy.” Socio-Economic Review 3 (2005): 173-208.

Krugman, Paul. “How Did Economists Get It So Wrong?.” The New York Times, September 9, 2009.

Krugman, Paul. Geography and Trade. Massachusetts: The MIT Press: 1993.

Obstfeld, Maurice, and Kenneth Rogoff. “Global Imbalances and the Financial Crisis: Products of Common Causes.” Paper prepared for the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Asia Economic Policy Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, October 18-20, 2009.

Öniş, Ziya, and Ali Güven. “The Global Economic Crisis and the Future of Neoliberal Globalization: Rupture versus Continuity.” GLODEM Working Paper Series 01-10. Center for Globalization and Democratic Governance, Koç University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2010.

Ötsch, Walter O., and J. Kapeller.”Perpetuating the Failure: Economic Education and the Current Crisis.” Journal of Social Science Education 9 (2010): 16-25.

Payne, A. “How Many Gs Are There in ‘Global Governance’ After the Crisis? The Perspectives of the ‘Marginal Minority of the World’s States?.” International Affairs 86 (2010): 729-740.

Prasad, Eswar, and M. Ding. “Debt Burden in Advanced Economies Now a Global Threat.” Financial Times, July 31, 2011.

Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth Rogoff. This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press: 2009.

Smiley, Gene. Rethinking The Great Depression.Chicago: Ivan R. Dee: 2002.

Stiglitz, Joseph. “Regulation and Failure.” In New Perspectives on Regulation, edited by Moss, and J. Cisternino. Cambridge: The Tobin Project, Inc.: 2009.

Sweezy, P., and H. Magdoff. Stagnation and the Financial Explosion. New York: Month- ly Review Press: 1987.

Wade, Robert. “Financial Regime Change.” New Left Review 53 (2008): 5-21.

Wade, Robert.“Beware of What You Wish For: Lessons for International Political Economy from the Transformation of Economics.” Review of International Political Economy 16 (2009): 106-121.

Wolf, Martin. “Why It is so Hard to Keep the Financial Sector Caged.” Financial Times, February 5, 2008.

Footnotes[+]

| ↑1 | The earlier version of this paper presented at Koç University-Kyoto University International Symposium on “Sustainable and Innovative Development”, Koç University, Istanbul (September, 2011). We are grateful to the participants for their valuable comments and suggestions. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ziya Öniş and Ali Güven, “The Global Economic Crisis and the Future of Neoliberal Globalization: Rupture versus Continuity”, (GLODEM Working Paper Series 01-10, Center for Globalization and Democratic Gover- nance, Koç University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2010). |

| ↑3 | “When Fortune Frowned,” The Economist, October 9, 2008, 3. |

| ↑4 | Anthony Payne, “How Many Gs Are There in ‘Global Governance’ After the Crisis? The Perspectives of the ‘Marginal Minority of the World’s States?,” International Affairs 86 (2010). |

| ↑5 | See the London G20 summit’s final communiqué: G20, “The Global Plan for Recovery and Reform”, Communiqué of the G20 Summit, London, April 2, 2009, accessed January 20, 2012, <www.g20.org>. |

| ↑6 | Paul Sweezy and Harry Magdoff, Stagnation and the Financial Explosion (New York: Monthly Review Press:1987). |

| ↑7 | Greta Krippner, “The Financialization of the American Economy,”Socio-Economic Review 3 (2005). |

| ↑8 | Gerald A. Epstein, “Introduction”, in Financialization and the World Economy, ed. Gerald Epstein, (Massachu- setts: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2005), 3-16. |

| ↑9 | Maurice Obstfeld and Kenneth Rogoff, “Global Imbalances and the Financial Crisis: Products of Common Causes”, (paper prepared for the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Asia Economic Policy Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, October 18-20, 2009), 16. |

| ↑10 | James Crotty, “Structural Causes of the Global Financial Crisis: A Critical Assessment of the ‘New Financial Architecture’”, Cambridge Journal of Economics 33 (2009): 575-576. |

| ↑11 | Maurice Obstfeld and Kenneth Rogoff, “Global Imbalances and the Financial Crisis: Products of Common Causes”, 2. |

| ↑12 | Krishna Guha, “Paulson Says Crisis Sown by Imbalance,”Financial Times, January 1, 2009; and Ben S. Bernanke, “Financial Reform to Address Systemic Risk,” (speech delivered at the Council on Foreign Relations, Washington D.C., March 10, 2009 |

| ↑13 | Maurice Obstfeld and Kenneth Rogoff, “Global Imbalances and the Financial Crisis: Products of Common Causes”, 35. |

| ↑14 | Eswar Prasad and Mengjie Ding, “Debt Burden in Advanced Economies Now a Global Threat,”Financial Times, July 31, 2011. |

| ↑15 | Ziya Öniş and Ali Güven, “The Global Economic Crisis and the Future of Neoliberal Globalization: Rupture versus Continuity,” 479. |

| ↑16 | Charles P. Kindleberger, The World in Depression, 1929-1939 (London: University of California Press: 1973). |

| ↑17 | Eric Helleiner, “A Bretton Woods Moment? The 2007-2008 Crisis and the Future of Global Finance,” Inter- national Affairs 86 (2010). |

| ↑18 | Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press: 2009), 233-237. |

| ↑19 | Gene Smiley, Rethinking The Great Depression (Chicago: Ivan Dee: 2002), 13-14. |

| ↑20 | It is important to underline that “swift recovery” is different than “sustainable ” The recovery after the recent crisis is swift but proved unsustainable. Therefore a possible “double dip” in the following months may change the entire story. |

| ↑21 | Paul Krugman, “How Did Economists Get It So Wrong?,” The New York Times, September 9, 2009. |

| ↑22 | Sheila Dow, “Mainstream Methodology, Financial Markets, and Global Political Economy”, Contributions to Political Economy, 27 (2008). |

| ↑23 | Henry Farrell and Martha Finnemore, “Ontology, Methodology, and Causation in the American School of International Political Economy,” Review of International Political Economy 16 (2009). |

| ↑24 | 24 Walter O. Ötsch, and J. Kapeller,”Perpetuating the Failure: Economic Education and the Current Crisis,” Journal of Social Science Education 9 (2010). |

| ↑25 | Benjamin J. Cohen, International Political Economy: An Intellectual History (Princeton: Princeton Univer- sity Press: 2008), 141. |

| ↑26 | Robert Keohane, “The Old IPE and the New,” Review of International Political Economy 16 (2009). |

| ↑27 | İsmail Ertürk, Adam Leaver, and Karel Williams, “Hedge Funds as ‘War Machine’: Making the Positions Work,” New Political Economy 15 (2010). |

| ↑28 | Robert Wade, “Beware of What You Wish For: Lessons for International Political Economy from the Transformation of Economics,” Review of International Political Economy 16 (2009):117. |

| ↑29 | Paul Krugman, Geography and Trade (Massachusetts:The MIT Press: 1993). |

| ↑30 | Geoffrey M. Hodgson, “The Great Crash of 2008 and the Reform of Economics,” Cambridge Journal of Economics 33 (2009): 1209 |

| ↑31 | Robert H. Wade, “Financial Regime Change,” New Left Review 53 (2008):6 |

| ↑32 | Andrew Baker, “Restraining Regulatory Capture? Anglo-America, Crisis Politics and Trajectories of Change in Global Financial Governance,” International Affair 86 (2010). |

| ↑33 | John Gapper, “After 73 Years: The Last Gasp of the Broker-Dealer,” Financial Times, September 15, 2008; and Peter Gowan, “Crisis in the Heartland: Consequences of the New Wall Street System,” New Left Review 55 (2009): 8-10. |

| ↑34 | Martin Wolf, “Why it is so Hard to Keep the Financial Sector Caged,” Financial Times, February 5, 2008. |

| ↑35 | David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press: 2005), 33 |

| ↑36 | Crotty, “Structural Causes of the Global Financial Crisis: A Critical Assessment of the ‘New Financial Architecture,’” 577. |

| ↑37 | Baker, “Restraining Regulatory Capture? Anglo-America, Crisis Politics and Trajectories of Change in Global Financial Governance,” 652. |

| ↑38 | “President Obama Calls for New Restrictions on Size and Scope of Financial Institutions to Rein in Excesses and Protect Taxpayers,” The White House, January 21, 2010, accessed <http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-pressoffice/ president-obama-calls-new-restrictions-size-and-scope-financial-institutions-rein-e> |

| ↑39 | Gowan, “Crisis in the Heartland: Consequences of the New Wall Street System,” 20. |

| ↑40 | Baker, “Restraining Regulatory Capture? Anglo-America, Crisis Politics and Trajectories of Change in Global Financial Governance,” 648. |

| ↑41 | Jonathan Kirshner, “The Study of Money,” World Politics 52 (2000): 433. |

| ↑42 | Joseph E. Stiglitz, “Regulation and Failure”, in New Perspectives on Regulation, ed. D. Moss, and J. Cisternino (Cambridge: The Tobin Project, Inc.: 2009). |

| ↑43 | Wade, “Financial Regime Change,”12. |

| ↑44 | Hodgson, “The Great Crash of 2008 and the Reform of Economics,” 1214. |

| ↑45 | John M. Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (London: St. Martin’s Press: 1960),159. |

| ↑46 | Ben Fine, “Neo-liberalism in Retrospect- It’s Financialization, Stupid,” (paper prepared for Conference on Developmental Politics in the Neoliberal Era and Beyond, Center for Social Sciences, Seoul National University, 22-24 October 2009). |