Mustafa Onur Tetik

Hitit University

This article seeks to expand the discussion on Methodological Nationalism (MN)within the discipline of International Relations (IR), to contribute to MN literature from the perspective of IR studies and to evaluate the prevalence of MN in the field by the quantification of selected works. To achieve these goals, the article, firstly, recapitulates the general MN literature and critically evaluates this discussion in IR. Later, it identifies the forms of MN as they appear in IR with two faces: Level of analysis (nation-as-arena) and unit of analysis (nation-as-actor). Secondly, the article proposes a method to assess the prevalence of MN through quantification. Finally, the article applies its method to IR works to address the question of how widespread MN is in academia in Turkey. The findings demonstrate the proportional pervasiveness of MN within the IR community of Turkey, which is part of the “periphery” in the discipline. The findings also let us draw some hypothetical conclusions

1. Introduction

The rise of populist nationalism/xenophobia in the “West” and the anti-Western nationalism in the “East” contaminating rational political deliberation and processes have recently becomemuch debatedtopics. Even though they are deemed a form of backlash to the socio-economic effects of hyper-globalization on local populations, nationalist sentiments and discourses are not novel phenomena. Miscellaneous shades of nationalism have been sneaking into our minds and daily lives as “banal”[1]practices for so long that we do not even recognize them as such.The social scientific literature is one of the strands of the nationalistic ecosystem that naturalizesthe nation-state order among societies. Social scientists problematize various aspects of rising populism and “denaturalize” banal nationalisms, but the question remains:How much does academia itself normalize the nation(-state) as the default configuration of political and societal order? To criticize their own role in this naturalization and to broaden the contours of social inquiry, scholars came up with the concept,and critique,of “methodological nationalism” (MN).

Despite the growing interest in other disciplinary traditions, the social scientific literature on MN is dominated by sociology, more specifically by migration studies. MN is not less pertinent to International Relations (IR) than to sociology, yet it is apparently understudied in the discipline. This article seeks to expand the discussion on MN within the discipline of IR, to contribute to MN literature from the perspective of IR studies and to evaluate the prevalence of MN in the field by the quantification of selected works.To achieve these goals, the article first recapitulates general MN literature and critically evaluates the discussion in IR. Later, it identifies the forms of MN as they appear in IR with two faces: Level of analysis (nation-as-arena) and unit of analysis (nation-as-actor). Secondly, the article proposes a frameworkto assess the prevalence of MN through quantification. This methodical venture can be considered the first attempt in the literature to quantitatively assess MN and that might be developed and applied in alternative settings with modifications.Although the prevalence of MN in academia is often alleged, as can be seen in the literature used in this article, there is alack of a methodically systemized empirical study to prove this contention. Therefore, MN discussions mostly stay at the theoretical level.

Finally, the article applies its method to IR works to address the question of how widespread MN is in the academia of Turkey as a “peripheral” country. As Pınar Bilgin conveyed in her empirical work, IR studies in Turkey are deemed globally “peripheral” in the discipline because of their dependence on the theoretical and methodological paradigms grown in the “core/center” countries.[2] Peripherality is germane in the context of MN owing to the intellectual division of labour in academia, including the discipline of IR, in which universal theorizing is primarily the business of the core whereas the periphery is busy with the particularities and/or case studies.[3]Scholarly interest in “national” particularities/localities as the case studies of the theories grown in the core has great potential to lead a researcher to become epistemologically entrapped by MN. Turkey objectively qualifies for this criterion as a quintessential example of a peripheral country where IR studies are steadily expanding and attention to foreign policy has piqued in recent years. Furthermore, as Chiara Ruffa states, a researcher can adopt a “convenience case selection approach” and choose a single case because of linguistic capability (Turkish) and the research interest of the author.[4]Nevertheless, this subjective point may prove to be invaluable as it may lay the groundwork for comparative research contrasting MN in the core and the periphery.

This article methodically selects and hand-codes relevant research articles and PhD theses based on their MN orientations. The findings demonstrate the proportional pervasiveness of MN among the IR community in Turkey and lets us draw some hypothetical conclusions, which have the potential to be a springboard for further research on the MN-IR nexus. This article itself might seem to be trapped into the epistemological circle of MN, and it is thus self-contradictory. However, this research is neither a normative/critical political theory piece nor a critique of MN. The goal of the article is to point out the forms of MN in the discipline of IR and to empirically reveal its prevalence in the IR academia of Turkey as an example of a “peripheral” country. Therefore, there is nothing performatively contradictory in that this article is also epistemologically “nationalist”.

2. Methodological Nationalism

Anthony D. Smith argued in 1979 that the study of “society” equates to the analysis of nation-states’ societies almost without question.[5]This society/nation-state equation has been known as MN. In social scientific inquiry, MN is framing modernity with a national principle, taking “national” societies or states for granted as the “natural” units of analysis and the territorialization of social scientific imagination through the boundaries of nation-states.[6] In a nutshell, MN means the self-isolation of social scientific inquiry into exclusive and sealed national “containers”[7] consolidating the nation-state system. The criticism of MN, thus, rapidly became fashionable within the critical circles of various disciplinary fields, most significantly in sociology, to ensure that the nation-state framework is not the only epistemological ground to empirically study and analyse societies, politics, or economics.[8]As Sutherland observes, “Though scholars across the humanities and social sciences have been questioning nation-state-centric analyses for some time, the academy is still far from a Kuhnian paradigm shift away from MN”.[9]

The level of the invisibility of ideology as a natural and universal habit determines its degree of power.[10] Since nationalism, as a “banal” practice, “is present in the very words which we might try to use for analysis”, a researcher can only modestly “draw attention to the powers of an ideology which is so familiar that it hardly seems noticeable.”[11] The employment of MN in a study is not necessarily a testimony of the ideological or political nationalism of the researcher.[12] On the contrary, there are debates in various countries, including Turkey[13], on academia for supposedly being the bastions of “left-wing” or “liberal”[14] bias and hegemony. Nationalism studies, especially, were criticized for their biased investigation of nationalism to prove that it is a form of “false consciousness.”[15]MN is not essentially tied to the political orientation of a scholar, which makes nationalism ubiquitous and successful as an ideology.

The weight of nation-states in social scientific inquiry is not a ramification of nationalists’ sinister central plan. Firstly, social scientific inquiry requires limited societal and spatial contexts or levels of analysis. MN has an apparent capacity to solve the problem of contextualization because “it treats the territory of the nation-state as a clearly delimited context, characterized by a unified set of institutional arrangements and a relatively high degree of social, cultural, political and economic homogeneity.”[16] Secondly, there must be units of analysis for social scientific endeavours. Nation-states supposedly have been the most coherent (considering their size) and significant “unitary” political organizations to whom anthropomorphic actorhood is ascribed by researchers more easily than others since, at the latest, the beginning of the 20th Century. It is not a coincidence that the critiques of MN are pioneered or promoted by scholars studying migration or globalization. Their areas of expertise propel them to transcend the traditional societal and spatial boundaries of nation-states under the contemporary circumstances of increased global connectivity and mobility. As globalization widens and deepens, it becomes hard to use a particular nation-state with fixed and sealed borders as the ontological or epistemological ground in scholarly works. These critical scholars offer alternative contexts and units of analysis to unchain their own and others’ scientific investigations from the epistemic constraints of MN.[17]

3. Methodological Nationalism in International Relations

The discussion on MN is more prominent in sociology than in other disciplines, but it is also highly relevant for IR.[18]In IR, nation-states are naturalized as “units” representing a “societal” identity that exclusively belongs to a fixed, sealed and socially constructed “space”. The nation-state is “a spatial configuration [that] brings together identity, territory, and the management of lethal violence in such a way that it can be conceptualized as a unit, and that unit interacts with other similarly constituted units.”[19]IR traditionally engages in disclosing the patterns of interrelations of these societal units, namely nation-states, the organizational agents of societies in the inter-national system. The concept of inter-“national” is deemed a misnomer by some critical voices in IR because, according to them, what we observe in the system is inter-“state” relations. The “inter” prefix reinforces boundaries instead of making them porous.[20]The national ontologically precedes the international because “nationally bounded social was also the origin and the cause of the international”.[21]The orthodox geopolitical distinctions of “inside-outside” or “internal-external “are predicated on the territorialized space of the nation-state. The comparative analyses of IR essentially function on the basis of MN.[22]Studies of regionalism in IR are also often premised upon MN, which reifies the dichotomy between “region” and “state.”[23] The focused side of these dichotomies in an IR work determines the investigative level of analysis.

Even though some have argued that “Immanuel Wallerstein’s world-systems theory, in the early 1970s, was the first systematic break with methodological nationalism,”[24] the critique of MN is understudied in the discipline of IR. We can identify two rationales behind this oversight. Firstly, MN is the “disciplinary default position” for IR; basic conceptual distinctions, theory-building, and construction of cases and data in the discipline are mainly based on MN in the field.[25]The “international system argument” of mainstream IR, preaching that the international system is composed of formally analogous national units, is immanent to MN.[26]IR traditionally “assumed that nation-states are the adequate entities for studying the world.”[27]The nation has been considered as “the most comfortable resting place” because it is “a stable point of focus.”[28]The discipline is “almost entirely constructed on the assumption that humanity is inevitably and unchangeably divided into nation-states,”[29]which is the meta-theoretical premise of MN.

Secondly, the critique of MN in the discipline is disguised within critical theories. The supposed over-valuation of nation-states is shared by the most influential paradigms of IR, and MN is challenged by critical approaches, which are at the periphery of the discipline.[30]The hegemonic paradigm of state-centrism, and its by-products like the conceptual dichotomy of inside-outside, are the concomitants of MN in IR. For this dominant axiom, state-centrism in IR is as natural as being tree-centric in a theory of the forest.[31]State-centric approaches “operated with assumptions of methodological nationalism that treat the state as a natural social and political form.”[32]Critical theories,which have echoed in IR in the form of the aforementioned dominant principles, have problematized the nation-state-centric creed of MN without being vocal about MN’s label.[33] Radhika Mongia refers to this state-centrism as “methodological stateism” as a form of MN.[34]To Daniel Chernilo, the critique of the dominant theoretical principle of the domestic analogy in IR is a reflection of broader debates on MN.[35]

Ulrich Beck and Natan Sznaider propose the “methodological cosmopolitanism” of the discipline of sociology to replace MN[36] in IR, as it has been suggested that studying world politics as a globally “single socio-political space” instead of an “international system” composed of multiple sealed territories would more properly reflect the current conditions of the world.[37]In disciplinary practice, for instance, we observe that the authors/editors of one of the most used introduction textbooks of IR worldwide state that they intentionally named the book as “The Globalization of World Politics” instead of International Relations/Politics.[38] Furthermore, there is also the historical sociology aspect of the nation/state question in IR. Historical Sociology in IR does not only question the nation-state system in terms of the validity of presumed cohesion between nation, territory and government, but it also problematizes the very definition of the state as we know and employ it in our works today.[39] These reflexive outlooks to the disciplinary paradigms and axioms such as nation-state-centricity indicated the criticism of MN without directly mentioning the concept.

4. Two Forms of Methodological Nationalism in International Relations

The scholarly critiques of MN in IR challenge the tacit naturalization of the nation-state system through scientific discourse. The critiqued axiomatic forms of MN appearing in IR can be outlined as follows: (1) national units’ isolation and self-sufficiency, (2) natural, normal or given political borders, (3) the neat dichotomies and distinctions such as domestic/international or inside/outside, (4) the priority of national sense of belonging over other individual identities, (5) the uniformity/similarity of states and individuals, (6) the state-centric perspective on actorhood, (7) territory-population-national identity cohesion.[40] The list can be expanded, yet these are the main conceptual pillars of MN attacked by the pundits. These controversial axioms of MN spring from two major analytical issues within IR: Level and unit of analysis questions.

MN is built on the compression of two main contexts: societal (national) and spatial (territorial) analysis; “an exclusive and mutual embeddedness of social and territorial space.”[41] “States are either conceptualized as actors (corporate agents) or arenas (territorial spaces)” in which national identity and territory are intertwined.[42] The conceptualization of IR research through the prism of the nation-state system reflects these two main contexts as “unit of analysis (actor)” and “level of analysis (arena)” because the (nation-)state “is the most frequently studied unit or level of analysis in international relations.”[43] As Berkowitz argues, the question of level or unit of analysis in IR research manifests itself as the methodological problems of “using aggregate data in statistical analyses,” “defining actors in international relations theory” and “describing the relationship between systems and the actors within those systems.”[44] These problematiques are also germane to the unbearable lure of MN in IR.

(1) Level of analysis (nation-as-arena): The term “level of analysis” entered the conceptual lexicon of IR through David Singer’s discussion[45] of the “three images” of Kenneth Waltz[46],“the principal prophet of neorealism”[47] in IR. The search for the “context” or “level” within which we examine a topic leads us to the “level of analysis” question.[48]To Waltz, there are three “levels of analysis: the individual, the state and the state system.”[49] Later, Singer denounced the “trichotomization” of the issue, “simply eliminated the individual level and kept Waltz’s other two images.”[50] He contended that there are two “widely employed levels of analysis: the international system and the national sub-systems.”[51]Waltz’s first level, the individual, is an integral component of national sub-systems. The dualistic level of analysis distinction is highly pervasive in various mainstream IR paradigms, including constructivism (reductionist-systemic analysis / macro-micro levels/agent-structure debates).[52]Both of these prepotent levels of analysis (international and state levels) are ontologically predicated on the nation-state as the institutional axis separating the layers of IR research.

Though the nation-state is overwhelmingly taken as a “unitary actor” at the “systemic level (international) analysis,”[53] it is also a “level” which is “an agglomeration of individuals, institutions, customs, and procedures.”[54] IR scholars often focus on sub-national units/individuals, but they still deem these agents within a national whole/context. Even when an IR study does not employ the nation-state as a monolithic actor, it may fall into MN’s trap by investigating alternative actors via a national framework as a sealed “arena.” Explaining and understanding IR through the aforementioned sub-national actors or objects make the nation-as-arena the universe of the units under scientific foci. Cities, sub-regions, supra-regions, cyber-space or the world system as a whole might be alternative spatial contexts/universes to the nation-as-arena unless their definition or operationalisation in research is reliant on the nation-state from the very beginning (e.g. Antalya as a “Turkish” city vs. Antalya as a “Mediterranean” or “touristic” city).

(2) Unit of analysis (nation-as-actor): Despite the upsurge in diversification, the “nation-state remains the basic unit of analysis in IR”[55] up to the present time. Nation-states are presumed to seek survival, power and interests as unitary “actors,” although the decision-making power is vested ultimately in individuals on behalf of nation-states.[56]IR is primarily concerned with what states do and how their policies influence other states, and thus IR is largely about states.[57]However, considering the nation-state as an “individual” actor possessing self-reliant agency turns the nation-state into a “unit” instead of a “level.”“A level is a methodological tool employed only in relation to a specified unit.”[58]In the case of the nation-as-actor, the nation-state is the chief unit in the universe of agents in IR, which is “the systemic level.”

Nuri Yurdusev criticizes Singer’s usage of the level of analysis interchangeably with unit of analysis. To him, “level of analysis and unit of analysis are not identical, but interwoven” because when the former is about the framework/context of a study, the latter is concerned with the actor/object/unit/entity of the scientific inquiry.[59] Likewise, Owen Temby argues that “the ontological question, ‘who and what are the actors?’, is different from the methodological question, ‘what level of analysis are we using?’”[60] A level of the lower layer becomes the unit of the higher layer.[61] “For example, the bureaucracy level is the system at the individual level and the unit at the nation state level.”[62]The deployment of the nation-state as a unit within an IR work is a textbook case for MN. Civilization, tribe, ethnicity, gender, socio-economic class, institution, social movement, business, religion and even simple material-biological objects like “paprika”[63] are alternative units to be employed in IR research to overcome the theoretical boundaries. However, if these units are positioned as a unit within the context/framework of a nation-state, it would mean that the work still remains within the paradigm of MN (e.g. Hungarian paprika).

5. Methodology

This article aims at measuring the extent of the prevalence of MN in IR academia on territorial Turkey[64] via the quantification of contemporary methodological nationalist praxis. There are three methodical steps to assess MN’s proportional pervasiveness:

Stage 1 –Primary Sources: It is necessary to decide which academic literature has the potential to clue us into the regularity of MN. Since academic journals and dissertations are fundamental scholarly platforms and works, they are taken as the primary academic sources. It is also necessary to set a purposive and operable timeframe. The numbers of theses and journals and the timeframe need to be limited with objective parameters to acquire manageable and representative data. The timeframe is limited from 2015 to 2019 because 1) the collected data have to be recent to display contemporary situation,[65] 2) considering the immensity of collected data to evaluate, temporal restraint was a must to have a doable task,[66] 3) fewer years of data would not be adequate to demonstrate whether the quantitative findings are representative of the overall inclination of the present.[67]To determine the most relevant cases among the universe of IR journals and theses in Turkey, these paths are followed:

Journals: Scimago Journal & Country Rank of Scopus database (Elsevier)[68] is used to filter scholarly IR journals in Turkey based on their scientific influence. There are four journals under the Political Science and International Relations subject category from Turkey. These journals are All Azimuth, Journal of Economic Cooperation and Development (JECD), Uluslararası İlişkiler (International Relations) and Insight Turkey. Nevertheless, a methodical filtration is necessary to have a healthier source selection and analysis. JECD is eliminated because the journal belongs to the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, which is an international organisation. Insight Turkey is disqualified for the sake of the objectivity criteria of this research. Since Insight Turkey is not a general IR journal but is primarily devoted to Turkey’s affairs, it has great potential to cause sampling bias. The journal’s name itself already indicates MN. Therefore, the research articles that were published in “All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace” by the Center for Foreign Policy and Peace Research, İhsan Doğramacı Peace Foundation, and “Uluslararası İlişkiler” by the International Relations Council of Turkey during the last five years (2015-2019) are adopted as the sources of academic journals. Uluslararası İlişkiler and All Azimuth are also considered two of the top Turkey-based IR journals by the IR community in Turkey.[69]Publications other than original research articles such as book reviews, editorial notes, commentaries, translations and conference presentations are disregarded for this analysis. Special issues are not taken into consideration either since their case uniformity distorts the objectivity and balance of the data. Besides, there are articles in journals written by scholars with non-Turkish institutional affiliations. They are counted in the total figures, but the results of these researchers are also given separately in the analysis.

Theses: The Turkish Council of Higher Education’s (YÖK) theses archive (Ulusal Tez Merkezi/the National Centre of Theses)[70] is used to filter IR PhD theses submitted to universities in Turkey. However, in this case, it is essential to decide which universities can be considered more significant than others. To assess the popularity of IR, the data collection procedures were based on YÖK’s “Atlas of Higher Education Programs,”[71]which ranks universities in Turkey depending on the preferences of the most successful students. This factor indicates the popularity and achievements of universities in the Turkish context and the Atlas’s online portal sorts the academic programs based on academic departments. The YÖK Atlas provides objective criteria to select universities. The top ten IR (including “Political Science and International Relations” programs) departments (Koç, Bilkent, Galatasaray, ODTÜ, Boğaziçi, Bahçeşehir, Kadir Has, Ankara, Dokuz Eylül and Yeditepe Universities) that have PhD programs were chosen.[72] All IR PhD theses written in these universities (which are in the archive regardless of whether they are embargoed) during the last five years (2015-2019) are taken as the academic dissertation sources.[73]

Stage 2 –Coding Scheme: As previously noted, MN comes into view in IR research with two faces: Level of analysis (nation-as-arena) and unit of analysis (nation-as-actor). Therefore, the article scrutinizes the selected academic resources to identify whether each study employs nation (-state) as the level or the unit of its analysis. In the cases that nation is not methodologically operationalized in either way, but as any other object or abstraction within the analysis, we cannot impute MN to such works. MN types in theses and articles are coded as level (LA) and unit (UA) of analysis, and nation(-state) as object of analysis (OA) is not considered methodological nationalist practice. Whereas the types of UA are various, such as academia, individuals, educational institutions, politicians, concepts, states, etc., level types are limited to systemic, international and national LA.

Systemic Level: Is comprised of works exclusively focused on theoretical and methodological issues, merely discussing ideas of individuals and the global system. Such works are coded as OA because nation(-state) is neither level nor unit in these analyses.

International Level: Constitutes works based on the interstate relations or foreign affairs of a particular state. Such studies are coded as UA because nations appear as actors in such studies.

National Level: Refers to the publications investigating sub-national institutions and actors. These studies are coded as LA since units are analyzed within a national framework. Besides, comparative studies are coded as “cross-national”. They are put under the category of national LA.

The figures are coded by their publication years, as well as journal or university affiliations. These separate figures are aggregated as the final findings. Their percentages are also calculated because the numbers of articles and theses fluctuate by year, journal and thesis. Additionally, the articles and theses regarding Turkey are also coded as Turkey-R to show the extent to which academia in Turkey is inward-looking. To unravel the weight of comparative studies, the numbers and percentage distributions of cross-national level works are also presented. The works that have multiple units and levels of analysis are coded in by the interest priority of the study and marked as multi-level or multi-unit studies.

Stage 3 – Content Interpretation: The researcher first read abstracts of all the works to determine their levels and units. If the abstract did not spell out the analytical characteristics of a work, then the researcher went through the details of the article or thesis. Although the conceptual pair of level and unit of analysis is defined in general terms, their operationalization during research is not clear-cut and does not allow the researcher to resort to the automated or computational coding of content. The majority of examined studies did not contain explicit information about their LA and UA. Therefore, the researcher’s personal evaluation was necessary, and hand-coded content analysis was the appropriate way to measure the prevalence of MN. Even though “coding is not a precise science; it’s primarily an interpretive act”[74], hand-coding has critical pitfalls, such as the error margin of interpretation of the content and possible human-related arithmetic miscalculations. The latter is escapable and easily curable since it is basic math. The former aspect, on the other hand, can be addressed by scrutiny and setting clear objective parameters. Some works had suffered from serious ambiguities, internal contradictions, or omissions. Hence, clarifications regarding definitions and interpretations were essential. Below are main explanatory notes deduced from the complexities the researcher faced during the interpreting and coding processes:

6. Methodological Nationalism in IR Academia in Turkey (2015-2019)<

IR academia in Turkey has put itself under meticulous scrutiny and self-criticism in terms of both pedagogy and literature in recent years. This is not necessarily a symptom of self-negation, self-confidence, nor self-colonization of minds. It is, rather, a manifestation of an emerging scientific collective agency and self-consciousness. We can locate four main reasons behind this development: 1) The Republic of Turkey’s active role in international and regional politics. 2) The growing interest in IR studies in Turkey. 3) The rising numbers of publications in high-ranking journals by Turkish academics. 4) The rising self-awareness of the “Turkish IR community” as a distinct scientific collective and a local disciplinary identity. The combination of burgeoning academic productivity, collective self-awareness and interest has resulted in a chunk of disciplinary genealogy[75] and reflexivity[76]works by Turkish IR academics.

For instance, Ersel Aydınlı and Gonca Biltekin contend that Turkish IR academics are still part of a “fragmented community that does not actively engage in scholarly debates” and emphasize the scarcity of quantitative works that would “help Turkish IR build the foundations upon which synchronized theoretical and methodological development can be based”.[77] In another study, Aydınlı and Mathews pointed out that there is a visible underachievement of IR academics in Turkey regarding the development of homegrown theorizing. IR academia in Turkey is overwhelmingly interested in the application-level theorizing which is, basically, either the non-confirmation of existing theories in line with the peculiarities of locality or straightforward adoption of a theoretical model produced in the “core”.[78] Likewise, Pınar Bilgin and Oktay F. Tanrısever argue that IR academia in Turkey suffers from parochialism because it mainly engages in either “telling Turkey about the world, [or] telling the world about Turkey”.[79] This study on MN in Turkey’s IR community displays a parallelism with the existing self-reflexive literature. The prevalence of MN in Turkey seems to be a natural extension of the abovementioned parochialism, theoretical and methodological dependency, and peripherality of IR academia in Turkey.

Even though nationalism is a pervasive ideology among the Turkish public and a hot topic among scholars, MN is understudied in social sciences in Turkey. Handan Akyiğit’s recent article on MN, which is not directly relevant to the discipline of IR, does not address MN in academia. The study mainly focuses on nationalism theories to follow the roots of MN, but ends up confusing and conflating political nationalism with MN because the article takes MN in a very broad sense and disregards the nuance that MN is a strictly academic concept.[80] Hüsrev Tabak’s work is the only noteworthy assessment of MN in IR academia in Turkey.[81] However, his work on “the study of foreign policy in Turkey” suffers certain limitations. Firstly, despite the strong theoretical backbone, the illustrative source selection seems to be arbitrary and constrained for the sake of producing a neat theoretical categorization/periodization. Secondly, although the study eloquently introduces the concept, the analysis intermingles political nationalism and MN, causing conceptual confusion. His work focuses on the political instrumentalization of MN more than the meta-theoretical uniformity created by it. In another work, he critiques MN and goes beyond the constraints of the “national condition” via the application of “domestic global politics framework” to the Syrian civil war.[82]Even though this study is an original contribution to the critical literature to MN and an operationalization of an alternative methodology in a case related to “territorial” Turkey, the objective of the piece is not the evaluation of IR academia. The research and analysis here aimed at overcoming the shortcomings of the literature by systemic quantification of data and stripping MN off from political-ideological connotations in the scientific realm.

6.1. Academic Journals (All Azimuth and Uluslararası İlişkiler)

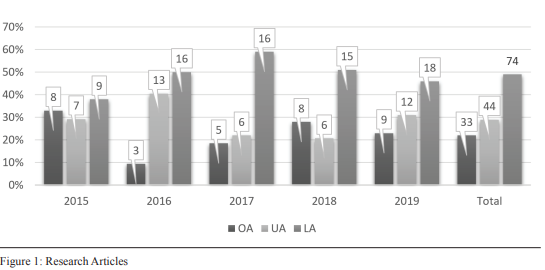

The following graph sheds light on the prevalence of MN in highly esteemed territorially Turkey-based IR journals between 2015-2019:

The bar graph displays the proportions of how nation-(state) is operationalized (level, unit or object of analysis coded as LA, UA and OA) in 151 research articles of respected and methodically selected Turkey-based IR journals.30 (%19.9) of them are written by researchers from non-Turkish institutions.[83]The numbers at the centre of columns are actual figures of articles. The first thing drawing attention in the graph is the prevalence of nation(-state) as LA, or nation-as-arena in other terms. The total numbers of articles taking the nation(-state) as a plane or framework that supposes the nation-state as a “container” of “domestic” interactions are almost equal to the nation(-state) as an actor and object, combined. Around 49% of the articles published in these journals between 2015-2019 focused on “internal” units within the nation-state arena. Various units of analysis such as political parties, elites, academia, exchange programs, education, parliaments, militaries, constitutions, and individuals among other things, are analysed at the national level. Approximately 9% of all articles are comparative studies focusing on domestic actors in a cross-national way. The proportion of LA is evidently higher than these two other meta-theoretical operationalizations of nation(-state) each year. We can infer that the IR literature (academic journals) in Turkey is mainly interested in developments “within” the framework of nation(-states) to explain international facts and events. This mainly “second image” oriented-ness of the IR literature in Turkey is in tandem with Turkish academics’ interest in constructivist[84] and neo-classical realist[85]approaches embracing domestic politics in theorizing. This form of MN seems to be the most prevalent one in the academic journals.

The rate of implementing nation-(state) as the main actor in the articles, namely UA, is around 29% among the covered research articles. The researchers axiomatically accepted the nation-states as unitary individual actors and analysed their relations with other fellow individual nation-states at the international level, mostly conducting foreign policy analyses of various nation-states. The personification of states as unitary actors strengthened further the naturalization of nation-states for IR academia in Turkey. According to our findings, only around 22% of covered research articles disregarded nation-(state) as a unit or level, but they brought nation-(state) into play as any other object within the analyses, which put spotlights on other various units like individuals, education, concepts, theories, methodology etc. at the systemic level. 78% of research articles in the two most relevant academic IR journals in Turkey can be considered within the circle of MN. 50% (15) of institutionally foreign-affiliated scholars’ articles took the nation-state as the level of analysis, 27% (8) of them are coded as the unit of analysis and 23% (7) of the works used the nation or the state as the object of analysis. These findings reveal to us that the statistical change brought by non-Turkish institutional affiliation is negligible since their particular level of MN was 77%, which is almost the same as the general average (78%).

These results substantiate the contention that Turkish academia, as part of the global periphery, does not showcase much interest in theoretical-conceptual construction endeavours in IR but mostly engages in hard, day-to-day and region-based international politics.[86] This situation indicates an important conclusion that the pervasiveness of MN is also related to centre-periphery relations within the IR discipline. One would expect fewer instances of MN in IR publications from the core. Cross-checking this argument will be the topic of a follow-up research study covering and comparing countries from both “centre” and “periphery.” Moreover, 37% of the covered articles are directly related to Turkey. This proportion does not reflect the results of TRIP (Teaching, Research and International Policy) 2018 surveys in Turkey.[87] TRIP results show that only 9% of IR scholars in Turkey define their main area of research/expertise as Turkish foreign policy.[88]On the contrary, this 37% is roughly in parallel with Aydınlı and Biltekin’s findings showing that 32.5% of the articles in all ISI journals and 35.1% of the studies in the four significant Turkey-based/focused journals[89]contain the word “Turkey”.[90] These figures are possibly an indication that IR scholars in Turkey write about Turkish affairs once in a while regardless of their main area of expertise. The results here show that the number of works on Turkish foreign policy is significant but not overwhelming in academia in Turkey. In a nutshell, findings derived from All Azimuth and Uluslararası İlişkiler research articles reveal that the most notable IR academic journal literature is profoundly methodological nationalist (≈78%) either in an epistemological or ontological way.

6.2. PhD Theses

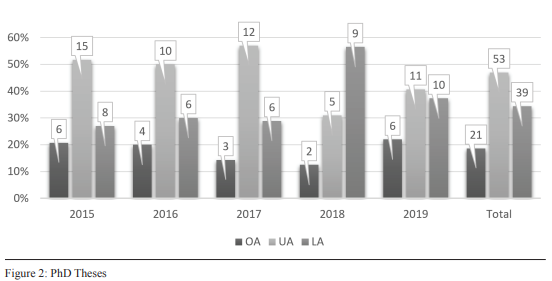

The graph below points out the degree of MN in PhD theses written in the most respected IR programs in Turkey between 2015-2019:

In comparison with research articles, PhD theses are more comprehensive works that are able to contain vast coverage of issues related to the selected topic or unit. The findings deduced from 113 selected PhD theses exhibit some parallels and divergences with the covered research articles. The first noteworthy dissimilarity is the proportional disparity between the two forms of MN, nation-as-arena and nation-as-actor. Unlike in academic journals, researchers in Turkey are more inclined to use nation(-state) as a UA more than a LA in their IR PhD theses. One can speculate where this difference stems from. For instance, the technical restraints of article-level works might impel scholars to narrow their focus down to the particularities of a nation-state. Whatever the reason is, around 47% of the PhD theses under scrutiny have taken nation(-state) as their UA. These studies mainly analyse the foreign policies of single states along with their bilateral or multilateral relations with other nation-states. Additionally, a nation-state’s interrelations with international organizations or nation-state institutions like intelligence services or public diplomacy operations within another national territory also feature prominently in the theses. This shows that scholars in Turkey are more interested in foreign policy analysis, and thus tend to portray the nation(-state) as an unproblematically unitary actor in their PhD works.

Secondly, the proportional prevalence of nation-as-arena in theses is around 34%. Early-career scholars focused on various units like migrants, reforms, companies, parties, ethnic politics, ideological groups etc. within a national framework. This form of MN confines these units to the neatly separated boxes of nation-states. Nevertheless, some of these works are also comparative studies. Around 12% of theses are cross-national works but still operate at the national level. This leaves around 19% of the works to adopt the nation(-state) as a non-focused object at the systemic or international level. The systemic level theses’ main interests are theoretical and conceptual critique or building. Besides that, some dissertations at the international level of analysis focus on various units like international organizations, international courts, IR discipline etc. Even though nation-states appear as units in such works, they are not the UA but subordinate or secondary factors/actors among others.≈ 81% of the systematically filtered PhD theses are methodologically nationalist one way or another. This proportion approximates to the number reached in the IR literature of academic journals (78%). Moreover, around 35%of dissertations are directly related to Turkey, which is a figure also similar to that derived from the journals (37%).Considering these journals and universities are the most “international” ones, we can easily reach the conclusion that, at least, roughly4/5 of IR academia in Turkey is methodologically nationalist, reproducing banal nationalist discourse within the social scientific environment that indirectly informs the general Turkish public and perceptually naturalizes and legitimizes the idea that the world is composed of competing nations and strictly demarcated exclusive territories.

7. Conclusion

Ulrich Beck and Natan Sznaider argue that a social scientist, as an “observer,” conducts MN by taking politically nationalist actors’ normative and socio-ontological claims as given facts. This normative claim is that “every nation has the right to self-determination within the context of its cultural, political and even geographical boundaries and distinctiveness.”[91]The social scientist also turns into a social actor operationalizing a normative perspective as a tacit act that “naturalizes “an “ideological” position. Beck suggests “methodological cosmopolitanism” to overcome the problems caused by MN, which is not only an epistemological alternative for widening transnationality and the “cosmopolitan condition”[92] of the present but also an opposite ideological stance itself. Beck withdraws to the point that “nation-states will continue to thrive,” but he also asserts that “national organization as a structuring principle of societal and political action can no longer serve as the orienting reference point for the social scientific observer.”[93]Although Beck and other critiques of MN claim the opposite, MN cannot be considered a “false consciousness” or a “scientific error.” It is a matter of ontological or epistemological choice. Nation-states’ dominating role in our modern world is an undeniable fact and thus their epistemological weight in social sciences is not surprising. Nation-states exist in various forms regardless of whether we normatively condone the universality of the nation-state system or not. Instead, MN is a type of “meta-theoretical bond “restraining the contours of social scientific research and is problematic, but indeed is not an “error.” Although it always contains the risk of an oversimplification of a complex world for ideal-typical convenience, to call MN an error would mean that the vast majority of the whole social sciences literature is erroneous.

This article highlighted the neglected role played by MN in IR research. It suggested that MN appears in IR literature in two garments: Level and unit of analyses. The prevalence of MN in social sciences has been widely argued. To quantitatively demonstrate whether this contention is empirically erected on solid ground, this study delved into the universe of IR research articles and PhD theses in Turkey. Methodically-determined primary sources granted us the proportional prevalence of MN in the context of IR academia in Turkey. According to the findings, ≈ 80% (journals: 78% and theses: 81%) of the covered works are methodologically nationalist. This means only one out of five studies transcended the frontiers of MN. The causes of such prevalent methodological praxis is debatable. It might be peripherality, academic dependency, nationalistic political culture or scientific indolence. Whatever it is, the results witness that the IR community in Turkey overwhelmingly reinforces the meta-theoretical normalization of nation(-states) in research. Considering the spill-over effect of the reproduction of MN literature, the lack of a statistical decreasing trend in MN in our findings, and global and local developments in nationalist policies mutually feeding themselves with academia, a significant breakthrough from this epistemological axiom does not seem near. Furthermore, nation(-state)’s role in studies either as a level or a unit also does speak for the disciplinary IR tradition in Turkey. The findings pointed out that the IR community of Turkey as a peripheral country is more interested in foreign policies of particular states and international hard/daily politics than theories, concepts, methodologies or abstractions. ≈ 80% is certainly high number, but to demonstrate the relative significance of MN in Turkey, we need a further comparative research. A comparison with a “core” country has a great potential to contribute to our understanding of disciplinary centre-periphery relations in IR.

Adamson, Fiona B. “Spaces of Global Security: Beyond Methodological Nationalism.” Journal of Global Security Studies 1, no. 1 (2016): 19–35.

Amelina, Anna, Thomas Faist, Nina Glick Schiller, and Devrimsel D. Nergiz, eds. Beyond Methodological Nationalism: Research Methodologies for Cross-Border Studies. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Amelina, Anna, Thomas Faist, Nina Glick Schiller, and Devrimsel D. Nergiz. “Methodological Predicaments of Cross-Border Studies.” In Anna Amelina et al., Beyond Methodological Nationalism, 1–22.

Aydın, Mustafa, and Korhan Yazgan. “Türkiye’de uluslararası ilişkiler akademisyenleri eğitim, araştırma ve uluslararası politika anketi – 2011.” Uluslararası İlişkiler 9, no. 36 (2013): 3–44.

Aydın, Mustafa and Cihan Dizdaroğlu. “Türkiye’de uluslararası ilişkiler: TRIP 2018 sonuçları üzerine bir değerlendirme.” Uluslararası İlişkiler 16, no. 64 (2019): 3–28.

Aydinli, Ersel and Gonca Biltekin. “Time to Quantify Turkey’s Foreign Affairs: Setting Quality

Standards for a Maturing International Relations Discipline.” International Studies Perspectives 18, no. 3 (2017): 267–87.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Julie Mathews. “Turkey: Towards Homegrown Theorizing and Building a Disciplinary Community.” In International Relations Scholarship around the World, edited by Arlene B. Tickner and Ole Wæver, 208–22. Oxon: Routledge, 2009.

Balcı, Ali, Filiz Cicioğlu and Duygu Kalkan. “Türkiye’deki uluslararası ilişkiler akademisyenleri ve

bölümlerinin akademik etkilerinin Google Scholar verilerinden hareketle incelenmesi.” Uluslararası İlişkiler 16, no. 64 (2019): 57–75.

Bartelson, Jens. “From the International to the Global?” In The SAGE Handbook of the History, Philosophy and Sociology of International Relations, edited by Andreas Gofas, Inanna Hamati-Ataya and Nicholas Onuf, 33–45. London: Sage Publications, 2018.

Beck, Ulrich. “The Cosmopolitan Condition: Why Methodological Nationalism Fails.” Theory, Culture & Society 24, no.7-8 (2007): 286–90.

–––. “The Social and Political Dynamics of the World at Risk: The Cosmopolitan Challenge.” Paper presented at the 26th Annual Congress of the Association of European Schools of Planning (AESOP), Ankara, 2012. Accessed September, 18, 2021. https://www.aesop-planning.eu/download/file/en_GB/aesop-silver-jubilee-congres-is-ankara-11-15-july-2012-facts-figures/lecture-by-ulrich-beck.

Beck, Ulrich, and Edgar Grande. “Varieties of Second Modernity: The Cosmopolitan Turn In Social and Political Theory And Research.” The British Journal of Sociology 61, no. 3 (2010): 409–443.

Beck, Ulrich, and Natan Sznaider. “Unpacking Cosmopolitanism for the Social Sciences: A Research Agenda.” The British Journal of Sociology 57, no. 1 (2006): 381–403.

Berkowitz, Bruce D. “Levels of Analysis Problems in International Studies.” International Interactions: Empirical and Theoretical Research in International Relations 12, no. 3 (2008): 199–227.

Bilgin, Pınar. “Uluslararası ilişkiler çalışmalarında “merkez-çevre”: Türkiye nerede?” Uluslararası

İlişkiler 2, no.6 (2005): 3–14.

Bilgin, Pınar, and Oktay F. Tanrısever. “A Telling Story of IR in the Periphery: Telling Turkey About

the World, Telling the World About Turkey.” Journal of International Relations and Development 12, no. 2 (2009): 174–79.

Billig, Michael. Banal Nationalism. London: Sage Publications, 1995.

Chernilo, Daniel. “The Critique of Methodological Nationalism: Theory And History.” Thesis Eleven 106, no. 1 (2011): 98–117.

–––. “Methodological Nationalism and the Domestic Analogy: Classical Resources for Their Critique.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 23, no. 1 (2010):87–106.

Cox, Robert W. “Social Forces, States and World Orders: Beyond International Relations Theory.” In Neorealism and Its Critics, by Robert O. Keohane, 204–54. New York: Columbia University Press, 1986.

Eagleton, Terry. Ideology: An Introduction. London: Verso, 1991.

Erozan, Boğaç. “Türkiye’de uluslararası ilişkiler disiplininin uzak tarihi: Hukuk-ı Düvel (1859-

1945).” Uluslararası İlişkiler 11, no. 43 (2014): 53–80.

Ertosun, Erkan, “Türkiye’de siyasi tarih çalışmaları: metodoloji sorunu ve bir çözüm önerisi olarak örnek olay çalışması.” Uluslararası İlişkiler 12, no. 48 (2016): 117–33.

Gille, Zsuzsa. “Global Ethnography 2.0: From Methodological Nationalism to Methodological Materialism.” In Anna Amelina et al., Beyond Methodological Nationalism, 91–110.

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double-Consciousness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Gusterson, Hugh. “Realism and the International Order After the Cold War.” Social Research 60, no. 2 (1993): 279–300.

Halliday, Fred. “State and Society in International Relations: A Second Agenda.” Millennium - Journal of International Studies 16, no. 215 (1987): 214–30.

Hameiri, Shamar. “Beyond Methodological Nationalism, But Where to for the Study of Regional Governance?” Australian Journal of International Affairs 63, no. 3 (2009): 430–41.

Hatzopoulos, Pavlos. The Balkans Beyond the Nationalism and Identity. London: I. B. Tauris, 2008.

Hellmann, Gunther. “Methodological Transnationalism – Europe’s Offering to Global IR?” European Review of International Studies 1, no. 1 (2014): 25–37.

Hobden, Stephan. International Relations and Historical Sociology. London: Routledge, 1998.

Hobson, John M. “The Historical Sociology of the State and the State of Historical Sociology in International Relations.” Review of International Political Economy 5, no. 2 (1998): 284–320.

–––. “The Poverty of Marxism and Neorealism: Bringing Historical Sociology back in to International Relations.” La Trobe Politics Working Paper no. 2. Melbourne: La Trobe University, School of Politics, 1994.

Hollis, Martin, and Steve Smith. Explaining and Understanding International Relations. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

İşeri, Emre, and Nevra Esentürk. “Türkiye’de uluslararası ilişkiler çalışmaları: merkez-çevre yaklaşımı.” Elektronil Mesleki Gelişim ve Araştırma Dergisi 2 (2016): 17–33.

Kelman, Herbert C. “The Role of the Individual in International Relations: Some Conceptual and MethodologicalConsiderations.” Journal of International Affairs 24, no. 1 (1970): 1–17.

Koos, Agnes Katalin, and Kenneth Keulman. “Methodological Nationalism in Global Studies and Beyond.” Social Sciences 8 no. 327 (2019).

Lacher, Hannes. “Putting the State in Its Place: The Critique of State-Centrism and Its Limits.” Review of International Studies 29, no.4 (2003): 521–41.

Lake, David A. “The State and International Relations.” In The Oxford Handbook of International Relations, edited by Christian Reus-Smit and Duncan Snidal, 41–61. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Martins, Herminio. “Time and Theory in Sociology.” In Approaches to Sociology, edited by John Rex, 246–95. Oxon: Routledge, 2015.

Mongia, Radhika. “Interrogating Critiques of Methodological Nationalism Propositions for New Methodologies.” In Anna Amelina et al., Beyond Methodological Nationalism, 198–218.

Moul, William B. “The Level of Analysis Problem Revisited.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 6, no. 3 (1973): 494–513.

Ongur, Hakan Övünç, ve Selman Emre Gürbüz. “Türkiye’de uluslararası ilişkiler eğitimi ve

oryantalizm: disipline eleştirel pedagojik bir bakış.” Uluslararası İlişkiler 16, no. 61 (2019): 23–38.

Özcan, Gencer. “‘Siyasiyat’tan ‘Milletlerarası Münasebetler’e: Türkiye’de uluslararası ilişkiler disiplininin kavramsal tarihi.” Uluslararası İlişkiler 17, no. 66 (2020): 3–21.

Pries, Ludger. “Configurations of Geographic and Societal Spaces: A Sociological Proposal between ‘Methodological Nationalism’ and the ‘Spaces of Flows’.” Global Networks 5, no. 2 (2005): 167–90.

Pries, Ludger, and Martin Seeliger. “Transnational Social Spaces: Between Methodological Nationalism and Cosmo-Globalism.” In Anna Amelina et al., Beyond Methodological Nationalism, 219–38.

Rosenberg, Justin. “Why is There No International Historical Sociology?” European Journal of International Relations 12, no. 3 (2006): 307–40.

Ruffa, Chiara. “Case Study Methods: Case Selection and Case Analysis.” In The SAGE Handbook of Research Methods in Political Science and International Relations, edited by Luigi Curini and Robert Franzese, 1133–147. London: Sage, 2020.

Saldana, Johnny. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: Sage Publishing, 2012.

Sassen, Saskia. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo, Princeton. NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Sezer, Burcu. “Türkiye’de kültürel iktidar tartışmaları: Cins Dergisi üzerinden bir değerlendirme.” Master’s Thesis, Ankara University, 2019.

Shaw, Martin. Theory of the Global State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Singer, J. David. “International Conflict: Three Levels of Analysis.” World Politics 12, no. 3 (1960): 453–61.

–––. “The Level-of-Analysis Problem in International Relations.” World Politics 14, no.1 (1961): 77–92.

Smith, Anthony D. Nationalism in the Twentieth Century. Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1979.

Sutherland, Claire. “A Post-Modern Mandala? Moving beyond Methodological Nationalism.” HumaNetten 37 (2016): 88–106.

Tabak, Hüsrev. “Metodolojik ulusçuluk ve Türkiye’de dış politika çalışmaları.” Uluslararası İlişkiler 13, no. 51 (2016): 21–39.

–––. “Transnationality, Foreign Policy Research and the Cosmopolitan Alternative: On the Practice of Domestic Global Politics.” In A Transnational Account of Turkish Foreign Policy, by Hazal Papuççular and Deniz Kuru, 41–68. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

Temby, Owen. “What are Levels of Analysis and What do They Contribute to International Relations Theory?” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 24 no. 4 (2015): 721–42.

Tickner, Arlene B. “Core, Periphery and (Neo)Imperialist International Relations.” European Journalof International Relations 19, no. 3 (2013): 627–46.

Turan, İlter. “Progress in Turkish International Relations.” All Azimuth 7, no. 1 (2018): 137–42.

Vergin, Nur. “Bilim Camiası ve Tanınma İsteği.” Doğu-Batı Düşünce Dergisi 7 (1999): 43–61.

Waltz, Kenneth N. Man, the State and War: A Theoretical Analysis. New York: Columbia University Press, 1959.

–––. Theory of International Politics. Long Grove: Waveland Press, 2010.

Weiß, Anja, and Arnd-Michael Nohl. “Overcoming Methodological Nationalism in Migration Research Cases and Contexts in Multi-Level Comparisons.” In Anna Amelina et al., Beyond Methodological Nationalism, 65–90.

Wendt, Alexander. Social Theory of International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Wilson, Matthew J. “The Nature and Consequences of Ideological Hegemony in American Political Science.” PS: Political Science and Politics 52, no. 4 (2019): 724–27.

Wimmer, Andreas, and Nina Glick Schiller. “Methodological Nationalism and the Study of Migration.” European Journal of Sociology 43, no. 2 (2002): 217–40.

Wimmer, Andreas, and Nina Glick Schiller. “Methodological Nationalism, the Social Sciences, and the Study of Migration: An Essay in Historical Epistemology.” International Migration Review 37, no. 3 (2003): 576–610.

Wolfers, Arnold. “The Actors in International Politics.” In Theoretical Aspects of International Relations, edited by William T. R. Fox, 83–106. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1959.

Yalçınkaya, Alâeddin, and Ertan Efegil. “Türkiye’de uluslararası ilişkiler eğitiminde ve araştırmalarında teorik ve kavramsal yaklaşım temelinde yabancılaşma sorunu.” Gazi Akademik Bakış 3, no. 5 (2009): 1–20.

Yazgan, Korhan. “The Development of International Relations Studies in Turkey.” Ph.D. diss.,

University of Exeter, 2012.

Yiğit, Celil. “Türk akademisinin realizmle imtihanı veya realizmi kullanma kılavuzu.” Panorama, March 18, 2020. Accessed August 7, 2020. https://www.uikpanorama.com/blog/2020/03/18/turk-akademisinin-realizmle-imtihani-veya-realizmi-kullanma-kilavuzu-celil-yigit/.

Yurdusev, A. Nuri. “'Level of Analysis' and 'Unit of Analysis': A Case for Distinction.” Millennium 22, no. 1 (1993): 77–88.

Zipp, John F. and Rudy Fenwick. “Is the Academy a Liberal Hegemony? The Political Orientations and Educational Values of Professors.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 70, no. 3 (2006): 304–26.