Helen Louise Turton

University of Sheffield

Disciplinary depictions using the core-periphery distinction are often premised on a ‘blurred’ and/or monolithic understanding of the core. For instance, the ‘core’ is often conceptualized broadly to include Western Europe and North America, or narrowly to refer to just the United States. Simultaneously the corresponding disciplinary self-images often refer to the core and the periphery as fixed and homogenous entities, which overlook the often diverse tendencies and hierarchies within the predefined space. This article therefore seeks to highlight the changing geographies of the core/periphery distinction in order to reveal the presence of different cores because there are different core properties. What this means is that the ‘core’ can appear in surprising spaces and occupy geographies that are normally associated with the periphery. In order to specifically illustrate certain workings and reach of the ‘core’ within spaces typically conceptualized as ‘peripheral’ this article will draw on existing data and research. The resultant empirical sketch will show how the ‘core’ is able to extend its reach and produce further epistemic hierarchies within peripheral spaces. In locating IR’s different cores and their hidden geographies this article aims to destabilize the core-periphery distinction in order to move beyond this disciplinary and disciplining archetype.

1.Introduction

In the discipline of International Relations (IR) the terms core and periphery are often used to capture the geography of unequal relationships of power and patterns of disciplinary dominance. As Stein Rokkan and Derek Urwin state the core-periphery is “a spatial archetype in which the periphery is subordinate to the authority of the centre. Within this archetype the centre represents the seat of authority”.[1] Whilst IR scholars frequently use the spatial dichotomy to highlight disciplinary exclusions in order to challenge them, the properties and boundaries of the core and periphery are not agreed upon, leading to competing understandings and therefore blurred or rather ‘fuzzy’ conceptions. For example, the ‘core’ is often conceptualized broadly to include, Australia, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, North America, and Western Europe, or narrowly to refer to the United States alone. However, these blurred geographical understandings of the core do not prevent those included in the respective delineated ‘cores’ and ‘peripheries’ from taking on a homogenous form. Meaning, that while the geographical borders of where the core is may shift, once decided upon, the core and periphery become fixed spatial entities with homogenous inhabitants. Resultantly, such monolithic conceptions tend to overlook the often diverse tendencies and stratified power relations within the ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ in order to give the terms categorical and visual functions and discipline those within each space.

The use of the terms core and periphery by scholars are premised upon different ways in which the core operates and thus gains its core status, which in turns prescribes the spatial limits of the core and periphery. For instance, the ‘core’ of the discipline has often been understood as a linguistic core. The most prestigiously perceived and influential journals in IR are arguably all English language journals. Theoretical texts are largely written in English and the major international conferences (for example ISA’s Annual Convention) are ones where English is the language of presentation and communication. Consequently, English is often seen as the lingua franca of IR and social sciences more generally[2]. Resultantly comparatively little international academic attention is paid to non-English language scholarship by the core[3]. The linguistic core is not the only way that the core is conceived. There are other core properties that have been captured in the literature. For instance, Turan Kayaoglu[4], Yong-Soo Eun and Kamila Pieczara[5] and Amitav Acharya and Barry Buzan[6] discuss an intellectual core, whereas Pinar Bilgin[7], Jonas Hagmann and Thomas Biersteker[8], and Peter Marcus Kristensen[9] point to an institutional core. Therefore, depending on the way one sees the function or property of the core its spatial dimensions will shift. This means that there are different cores, which occupy different spaces within IR.

The aim of this article is to problematize conceptions of the core and periphery in IR, and in doing so the article will make two claims: Firstly, the article will argue that there are different ways of conceptualizing the ‘core’ which result in different perceptions of where the core/periphery spatial boundaries reside. Secondly, the article will highlight hidden functions of the core and reveal the reach of the core within spaces usually perceived to be peripheral, thereby arguing that the core can appear in ‘surprising’ disciplinary spaces that are usually associated with the periphery. In making these claims the article will destabilize the categories of the ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ through showing the degrees of core stratification and aim to disrupt the way these categories condition IR scholars in order to facilitate a move beyond this distinction.

In order to do so the article will proceed as follows: Firstly, it will highlight the different geographies used when depicting the core and periphery in the literature to show the contested boundaries. Through reviewing the literature, it becomes clear that the geographies shift because different scholars are referring to different core properties, which results in the existence of different cores. The literature points to three different core/periphery relationships in the discipline of IR. These are 1) a linguistic core; 2) an intellectual core; and 3) an institutional/pedagogical core. The spatial configurations of these different core/periphery relationships will be presented in the second part of the article to show the reach of the ‘core’ and the creation of stratified power relations as a result of the construction of the ‘core’ within spaces normally conceptualized as peripheral. The third and final part of the article will offer a critical reflection of the findings and make a case for moving beyond the core/periphery disciplinary depiction.

To reveal the different cores that operate in the discipline of IR this article will utilize existing data and research on the discipline of IR. The article will draw on the 2014 TRIP faculty survey data[10], the 2018 Journal Citation Report for the subject area International Relations, the 2019 QS University World Rankings for Politics and International Studies, existing scholarly biographical information, and recent data produced by scholars working in the area of the ‘sociology of IR’ through their examinations of citation patterns[11], and journal content[12]. In revealing the ‘hidden’ workings of disciplinary power this article aims to draw attention to overlooked core dynamics so that they can be further investigated and challenged. Before revealing unseen sites of disciplinary authority the article shall first highlight the multiple depictions of the core and periphery employed by IR scholars in a first step to disturb this disciplinary imaginary.

2. Where is the Core and Periphery in the discipline of IR?

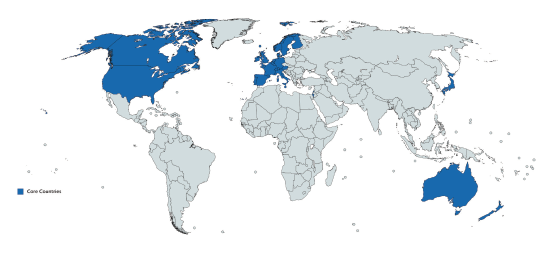

As noted in the introduction some depictions of the ‘core’ are more expansive than others, meaning they include more countries/geographically-bounded areas. Viewing conceptions of the core on a spectrum, the broadest belongs to scholars who argue that the ‘core’ of International Relations comprises the ‘West’. The West is presented as including Australia, Canada, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, the United States and Western Europe.[13] The term is used to capture the domination of Western thinking in IR that took hold because of ‘Western power’.[14] It signifies a shared intellectual and economic history, and a worldview.[15] Consequently, the periphery is designated as the spatial area outside of the West and takes on the label of the ‘non-West’.

Figure 1: Western Core

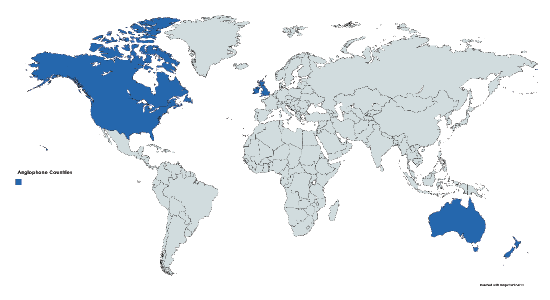

Moving along the spectrum, the next conception of the ‘core’ that populates that literature is that of the ‘Anglosphere’ or rather the ‘Anglophone’ countries. In this understanding the core consists of Australia, parts of Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States.[16] A shared language links this core; English. This conceptualization represents the dominance of a way of writing and communicating IR. To clarify, this understanding does not represent shared ideas, but rather a way of communicating those ideas and forums for dissemination. However, all is not equal within this ‘core’. Wayne Cox and Kim Richard Nossal[17] present a stratified view of this core; the United States is at the apex of the core, followed by the UK and the countries of what they term the post-imperial world (Australia, Canada, Ireland, and New Zealand) occupy the lower limits of the centre.

Figure 2: Anglophone Core

Not only is there stratification within the core there is also a corresponding hierarchy within the periphery. In defining the Anglosphere as the core[18] Western Europe is often placed in a semi-peripheral position.[19] It is excluded linguistically but is not as excluded as what Ersel Aydinli and Julie Mathews term the ‘true-periphery’.[20] Scholars in the semi-periphery have a degree of access and impact upon the centre due to their production of theory and research that has been acknowledged by the Anglosphere in publication channels. In this understanding one’s status is dependent upon one’s ability to contribute to English language discussions which take place in high-ranking international journals, which renders true-peripheral scholars as those “who hardly even have a place in the ‘House of IR’”.[21]

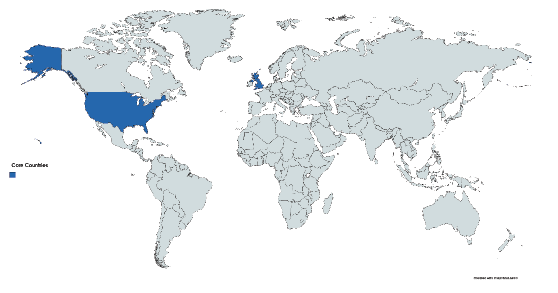

Another commonly used understanding of the core is where the core consists of the United States and the United Kingdom. Writing in 1985 Kal Holsti[22] captured this core;

Hierarchy seems to be a hallmark of international politics and theory. Most of the mutually acknowledged literature has been produced by scholars from only two or more than 155 countries: the United States and Great Britain. There is, in brief a British – American intellectual condominium.

Holsti’s depiction of IR is still shared by current commentators[23] who all note that IR's center is located in the US and UK. This understanding is premised on volumes of theory produced and institutional presence. The US and the UK have been awarded core status by certain scholars because each geographical locale has produced influential theoretical works, and arguably the majority of IR theory work. Furthermore, these IR communities have been claimed to host the key journals, publication presses, professional associations and universities.[24]

Figure 3: UK-US Core

However, there is a shared understanding by those who use this conceptualization that the US is the more dominant partner. Drawing on Johan Galtung’s theory of imperialism,[25] Jörg Friedrichs notes that the core is divided into a ‘centre of the core’ and a ‘periphery of the core’.[26] The US thus occupies the central space and the UK the outer limits of the core. While the UK might have disciplinary authority and power, it arguably does not exercise as much influence as the US over the ‘periphery’.

The periphery is this understanding of the core is the 'rest of the world'.[27] What is interesting in this depiction of the core is that those who employ it often do so for the purpose of constructing 'European IR' (usually understood as Continental Europe excluding the UK) as a counter-core force.[28] European IR is often presented as a potential challenger to the US-UK IR monopoly, thereby altering the core-periphery dynamics either to become a new core or part of the core itself. The reason that 'Europe' is awarded challenger status is again due to the role of theory. The volume of works produced in Europe is no longer the discipline's 'best kept secret'[29] as scholars in the US and UK are beginning to engage with such works.[30]

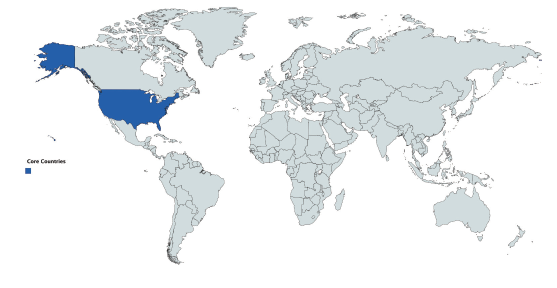

The final and the narrowest conception of the core belong to scholars who argue that the core of the discipline is the United States and the US alone.[31] The term 'American core' features prominently in the discipline and this understanding is used to make the corresponding claim that IR is an American dominated discipline.[32] In this conception the periphery comprises a vast space (i.e. the rest of the globe!), which inevitably means that certain IR communities are more peripheral than others. Those who argue that the US is the core of IR tend to organize the periphery hierarchically in the following manner: the UK is the least peripheral within the periphery; then the other Anglophone countries, Western Europe, Israel and Japan (i.e. those countries with a strong IR presence). Followed by China, Eastern European countries, Latin and South America, Russia, South East Asia and then 'the rest'. However, as Jörg Friedrichs and Ole Wæver note “regardless of whether we define them [countries/regions] as peripheries or semi-peripheries” all other IR communities “stand in a centre-periphery relationship to the American mainstream”.[33]

Figure 4: US Core

By illustrating the different conceptions of the core and periphery in the literature we can see that the boundaries of the core and periphery shift. What is included or excluded in the depictions depends on the perspective of the author and/or the claims that he/she wishes to make about the discipline. In other words, there are different core/periphery imaginaries because there are different and competing dominant disciplinary trends and hegemonic mechanisms in the global discipline that scholars wish to critique.[34]

3. IR’s Different Cores

Depictions of the core tend to be co-terminus with either ‘nation-states’ or regions, which then overlooks, as Peter Marcus Kristensen argues, that there are peripheries within the core (i.e certain Universities/preferred academic trends) and cores within the periphery (for example particular cities/capitals within specific countries). Meaning that certain depictions miss the diversity and stratification within the core and periphery.[35] Yet this stratification emerges because the core/periphery frameworks that have been used to highlight patterns of dominance and inequality draw upon different understandings of what it means to belong to the ‘core’. If we use these different conceptualizations and begin to construct an image of IR based on the different properties that have been awarded to ‘the core’ then we can begin to produce more nuanced depictions of where the core actually is and what it means to use the term ‘core’. In doing so we begin to disturb certain depictions and draw attention to parts of the ‘core’ that may exist within the commonly conceived ‘periphery’ allowing us to problematize and resist certain disciplinary dynamics and imaginaries. The article will now present IR’s different cores and their corresponding geographies, and in doing so will challenge the above core/periphery illustrations.

3.1. Linguistic core

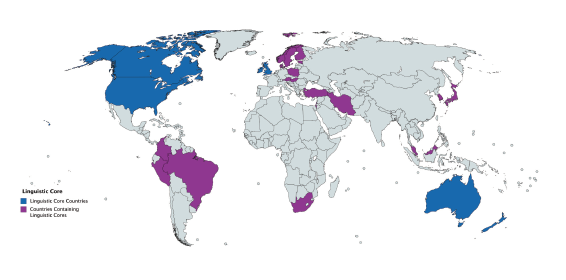

As mentioned in the above section one of the ways in which the core is located is through its linguistic properties. It is argued that English is the lingua franca of IR[36] and academia in general,[37] which means that English-speaking countries (the United States, parts of Canada, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand and the UK) are conceived to be ‘core’ due to their linguistic dominance and therefore advantage over other countries. The core position is due to the reality that unless research is written in English it stands little chance of being recognized and disseminated on an international level.[38] Non-English language research may attract attention within the confines of the national setting but unless it is translated or originally written in English it is unlikely to be picked up on the international scholarly radar and dispersed.[39]

Furthermore, the majority, if not all, of the perceived prestigious/influential IR journals are published in English. The TRIP 2014 Faculty Survey, for example, provides proof of the perceived influential roles of specific English language journals. When asked to ‘List the 4 journals that publish articles with greatest influence on the way IR scholars think about international relations’ the top 10 journals were: International Organization (53.44%), Foreign Affairs (38.36%), International Security (33.33%), International Studies Quarterly (25.4%), World Politics (20.77%), European Journal of International Relations (18.92%), American Political Science Review (13.23%), Foreign Policy (12.7%), Millennium (10.98%), and Review of International Studies (9.13%).[40]

Therefore, if one aims to enter into global debates then one is presented with a pressure to publish in English. The advantageous position that Anglophone scholars find themselves in means that their research stands a much higher chance of being accepted which effects the international composition of published research. Non-English speaking scholars are presented with an immediate hurdle to overcome in the quest to get their work recognized in the supranational academic community, and thus placed in a subordinate or rather peripheral position.[41] Commenting on publication practices in Poland Anna Dusak and Jo Lewkowicz claim “English has become much more readily available and is seen as necessary to succeed: its ideological position has changed and there is now a great demand for opportunities to learn and practice English”.[42]

The dominance of English as the language of IR has meant that ‘cores within the periphery’ have emerged in areas of Western Europe (especially parts of Scandinavia and Switzerland), Eastern Europe (in particular parts of Hungary, Poland and Estonia), Latin America (specifically Universities in the capitals of Colombia, Peru and Brazil), the Middle East (for example the University of Tehran offers undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in Political Science that are taught in English) South Africa, and parts of Asia (especially highly ranked Universities in parts of China, Japan, South Korea and Singapore) where scholars and students are taught in English and encouraged to write and publish in English.[43] This trend is intensified by the number of English-Speaking Universities opening up ‘satellite’ or rather branch campuses in ‘peripheral’ countries.[44] For example, the University of Nottingham (UK) has a campus in Malaysia offering a variety of undergraduate and postgraduate degrees taught in English including one in Asian and International Studies. The pressures to provide graduates with skills to enter the global marketplace and to be mobile has resulted in the emergence of English speaking hubs within ‘non-English’ speaking countries, thereby creating ‘cores’ within the periphery due to the adoption of the language of the ‘centre of the core’.

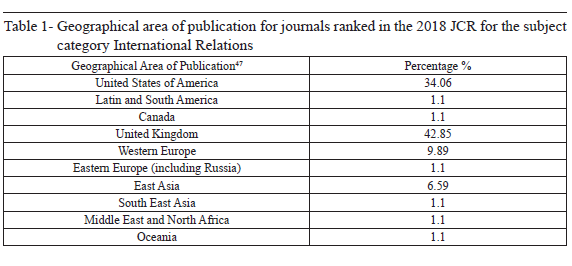

We can further see that the reach of the linguistic core extends beyond the ‘Anglophone’ countries if one looks at the 2018 Journal Citation Report (JCR)[45] for International Relations. There are 91 journals ranked in the 2018 JCR and 87 of them are published solely in English. The four journals not published solely in English are multi-language journals, which means that they are published both in English and the national language of the country of publication.[46] The dominance of English language publications in the JCR may not appear surprising or destabilizing to this particular core/periphery imaginary, yet if we look at the country of publication for each of the 91 journals we see evidence of the functioning of the linguistic core in the ‘periphery’ understood as non-Anglophone countries. For instance, as we can see from table one, 9.89% of the journals ranked in the 2018 JCR are from Western Europe, and 7.69% are from East and South East Asia. Roughly, a fifth of the journals ranked (20.88%) are published/managed in countries outside of the Anglosphere, despite all the journals are published in English.

The emergence of English language practices and standards within IR’s journals is partially due to the requirements of Clarivate Analytics[48] (the company who compiles the JCR and sets the standards for entrance into its many databases, journal archives, intellectual property management etc.). To be included in the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI), and therefore the JCR, numerous selection criteria have to be met. Clarivate Analytics, and formerly Thomson Reuters’s, selection process for the journals it covers is based on three key elements: Citation Data, Journal Standards, and Expert Judgment.[49] Within the category of ‘Journal Standards’ we can see the operation of what Kim Richard Nossal refers to as the core’s ‘linguistic imperialism’.[50] The journal standards criterion is comprised of a number of different factors: timeliness, international editorial conventions, English-language bibliographic information, and peer-review.[51]

Therefore, the SSCI does index and rank a number of foreign language journals as the selection process only asks for a minimum of abstracts or summaries in English, and all the bibliographic information. However, Clarivate Analytics/Thomas Reuter’s preference for the full text to be in English can be seen from the comments of key figures within Thomas Scientific. James Testa (Vice-President Emeritus for Editorial Development) openly claimed that Thomson Scientific “tries to focus on journals that publish their full text in English.”[52] Whereas Dr Eugene Garfield (creator of the Impact Factor, ISI Founder and Thomson Reuter Chairman Emeritus) stated, “If editors truly want wider notice of their journals by the international research community, they ought to publish articles, titles, abstracts, and cited references in English”.[53]

The clear preference for articles to be written and published in English is due to subscription rates and higher revenues. Publishers opt to create, maintain, and encourage the production and management of English language IR journals from countries outside of the Anglosphere because they can be guaranteed a bigger global audience and therefore subscription/download charges for their publications.[54] For example, in 2001 the journal International Relations of the Asia Pacific was launched. This publication is the official journal of the Japan Association of IR, and correspondingly is based in Japan and has an editor that is institutionally based at one of Japan’s Universities. However, the journal is published by Oxford University Press and all articles are written and published in English. The journal publishes a lot of scholarship from East-Asian academics thereby introducing such scholarship to a global audience and ensuring international dissemination. For instance, as of June 2019, the most read article in IRAP is by Yoshiko Kojo, who is a Professor in the Department of Advanced Social and International Relations at the University of Tokyo.[55] However, it seems that non-English speaking scholars find themselves in a Catch-22 type situation. As Duzak and Lewkowicz claim: “On the one hand, publishing in English is a way to gain international recognition. On the other, non-native speakers may face numerous linguistic, formal, organizational and ideological barriers which may influence their decision to look to the local market for publishing opportunities”.[56]

Language privileges a certain mode of thought, a certain culture and a certain way of constructing the truth.[57] Therefore, language is an exclusionary mechanism by its very nature, a form of domination, which results in subjugation. In this case the subjugation of non-native English speakers, and the emergence of ‘peripheral’ scholars adopting ‘core properties’ in order to challenge and resist their peripheral situation. Through looking at the core/periphery through the analytic gaze of language we can see the workings and reach of the core, in that the core has used its dominance to encourage others to assimilate and adopt the core language thereby creating cores within peripheries, or rather establishing subjugated cores within peripheries (the periphery of the core). As we can see from figure five the linguistic core extends into areas commonly depicted as peripheral, thereby occupying ‘new’ geographical terrain. Certain countries contain ‘linguistic cores’ in that English is the predominant mode of ‘speaking’ IR in specific contexts (such as particular University campuses) thereby creating epistemic hierarchies within certain states. Rather than being co-terminus with nation states as a whole the ‘peripheries of the core’ occupy particular geographical locations/areas within a given country. Resultantly there is stratification and the emergence of new hierarchies of power within particular countries as a result of the reach of the centre of the core. This ‘new’ imaginary (represented in figure five) draws attention to this stratification, and how the economy of knowledge in IR results in multi-level hierarchies.

Figure 5: Linguistic Core

3.2. Intellectual core

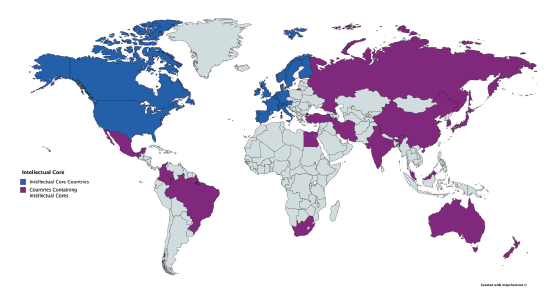

According to Andrew Hurrell; “as far as IR theory is concerned, nothing is really changing. It is still a neo-imperialist field of enquiry and control over the intellectual means of production has hardly shifted”.[58] Hurrell in essence is arguing that there is an intellectual core in IR, and this core is a Western one. When academics in IR talk of a ‘core’ they often refer to an intellectual or rather theoretical core, which takes the form of a volume of knowledge/intellectual production emanating from specific Western countries, and then the ‘core’ uses this dominance in volume to establish global theoretical preferences/practices.[59] On the surface the popular geographical imaginary of an intellectual Western core and non-Western periphery seems to be upheld. Despite theoretical pluralism in recent years[60] a growing body of literature and academic discussion (via conference themes, workshops) have lamented the lack of ‘non-Western IR theory.[61] The notion that theoretical knowledge is produced in the West and consumed in the non-West continues to populate the discipline.[62]

However, a closer look reveals that the landscape is changing, especially if we redefine what we mean by ‘non-western IR theory’ and accept hybrid theoretical efforts as ‘non-Western’ theoretical products. Often non-Western theoretical scholarly works are discounted because they are not conceived to be novel theoretical productions due to the incorporation of Western elements/concepts/points of reference/ideas.[63] The standard set by certain academics for non-Western theory to be conceptualized as a ‘non-Western theoretical endeavour’ is for the theoretical work to be something entirely new, without any reference to Western concepts, literature etc. This high benchmark is often coupled with a commitment to implicit Western standards of epistemology and therefore what constitutes ‘legitimate knowledge’.[64] As Amitav Acharya argues;[65]

A good deal of what one might bring into IR theory from the non-Western world may indeed be ‘worldly knowledge’. But other sources could be religion and cultural and spiritual knowledge that might not strictly qualify as ‘this-worldly’. They may lie at some vague intersection between science and spirituality or combine the material with the spiritual.

Non-Western theoretical accounts that draw on spiritual or religious texts have been excluded from being awarded the status of ‘theoretical knowledge’ due to their ‘non-worldly’ basis. As Aydinli and Biltekin note “when a periphery scholar nevertheless attempts to ‘do theory’, their work is likely to be dismissed as not ‘being theory’.[66] Hierarchies of knowledge in IR work to exclude grassroots and religious knowledge,[67] thereby creating the impression that there is no non-Western theory. However, if we accept such sources of knowledge and include ‘hybrid’ theoretical efforts then one begins to see the emerging plethora of non-Western IR theory in existence thereby destabilizing the West/Non-West, core/periphery imaginary.

For instance, Homeira Moshirzadeh[68] charts the development of IR theorizing by Iranian scholars based on Islamic texts.[69] Whereas Karen Smith examines the theoretical contributions of African IR scholars.[70] There is also a growing body of scholarship that has addressed the production of ‘Chinese IR theory’,[71] with the works of Yan Xuetong[72], Qin Yaqing[73], and Zhao Tingyang[74] being acknowledged as IR theory. Looking to Latin and South America, Carlos Escude’s Peripheral Realism[75], and Fernando Cardoso and Enzo Faletto’s Dependency Theory[76] are further examples of the existence of ‘non-Western IR theory’.[77] In their 2018 article Ersel Aydinli and Gonca Biltekin[78] analyse through citation scores the global recognition of 18 ‘non-Western’ IR theory works. Whilst some of the works examined, unfortunately did not amass recognition by the ‘centre of the core’ as measured by their citation numbers, one hopes that by drawing attention to such works through publication and discussion forums this will emerge in time. There is clearly still a large asymmetry in terms of volume of IR theory produced in ‘West’ compared to the ‘non-West’, but to solely focus on the imbalance helps to overlook the theoretical development taking place and the agency of peripheral scholars.

This exceedingly brief snap shot does not account for all the theoretical developments underway that could be categorized as ‘non-Western’.[79] The aim of this short overview is to show, as Raewyn Connell argues, that “theory does emerge from the social experience of the periphery, in many genres and styles”.[80] We need to recognize the multiple theoretical efforts that exist in the ‘non-West’ and challenge the existing geographical depiction that is based on a skewed understanding of what constitutes theory. To do so gives agency and recognition to different IR communities, and helps to limit some of the perverse effects that have emerged in the ‘search for non-Western IRT’. For example, claims of non-Western ‘ethnocentrism’ and the critique of ‘national schools of IR’ work to delegitimize such scholarship,[81] whereas claims relating to authority/authenticity of voice work to exclude and marginalize self-identified ‘peripheral’ scholars. When reflecting on ‘who or what is Asian IR’ Amitav Acharya notes the danger of reducing Asian IR to the work of scholars of Asian origin, based in Asia;[82]

Excluding or any kind of downgrading of their work [for example academics of Asian origin working in Western institutions] would be not only unfair, but also intellectually questionable. It also deprives scholarship on Asian IR a rich source of quality and breadth (especially in terms of theoretical and comparative perspectives), a good deal of which continues to come from outside of Asia. While indigenization is important, I would call for including any scholar anywhere working on Asian international issues as part of the Asian IR community.

Resultantly certain theoretical works can be (and have been) delegitimised from being categorised as ‘non-Western’ due to questioning the legitimacy of the positionality of the authors.[83] Whereas other works have been uncritically adopted and legitimated because of the author’s ‘origins’, thereby overlooking the potentially negative implications of such work.[84]

The ‘search for non-western IR theory’ has had a number of counter-productive implications, which often work to make less visible this growing body of theoretical scholarship. Hence it is key that scholars adopt a broader conception of what constitutes IR theory in order to recognize non-Western theoretical contributions. If we redefine what we mean by ‘non-Western IR theory’, and employ this understanding, a different geography of the discipline emerges.

Figure 6: Intellectual Core

If we adopt the different theoretical core/periphery imaginary depicted in figure six, then this would challenge the use of the problematic term ‘non-Western’. The concept of non-Western sets up a binary and reinforces the ‘non-West’ as the other and as the exceptional.[85] The label ‘non-Western’ reifies otherness, essentialises the non-West whilst also presenting it as something ‘exotic’.[86] Hence if we acknowledge hybrid theoretical productions we highlight the mutually constituting relationship between the ‘West’ and ‘Non-West’ thereby blurring the boundaries and reshaping the ‘core and periphery’, to show that there are ‘peripheries of the core’ within peripheral spaces. This then opens up the possibility for examinations of power, hierarchies of knowledge etc. within other spaces. As Odoom and Andrews note “we also need to be aware that, like all stories from other parts of the world, many African [and other] stories are prone to class, gender and other biases. Certainly stories are a reflection of power relations: who has a voice, and whose voice is capable of being heard”.[87] There are epistemic hierarchies in each IR community and this leads to exclusions and marginalisation. The ‘non-West’ is not immune from such disciplinary power relations, hence it is important to recognise the existing hierarchies and stratification of power within spaces that are typically considered peripheral. One needs to critically assess and challenge epistemic hierarchies within states not just between them.

Claims concerning IR’s intellectual core extend beyond the theoretical realm to the methodological. Assertions of American methodological dominance have been used to justify and explain depictions of the US as the core of IR. For instance, Thomas Biersteker has claimed that IR suffers from an American rationalist hegemony.[88] By this Biersteker means that the discipline of IR is dominated by rational choice methods as these are the core’s (US) preferred methods of studying international politics. According to the arguments of Biersteker,[89] Jørgensen and Knudsen,[90] Steve Smith,[91] and others, the US is in the authoritative position and has determined that IR should be studied using methods aligned to rational choice principles. This methodological centre arguably places all other methods in a subordinate position, and scholars who choose not to adopt such methods are allegedly marginalized due to their peripheral status.

Recent investigations into the global discipline of IR however have begun to question this assumption and therefore the depiction of the US as the core methodologically. The journal investigation conducted by Helen Louise Turton revealed that the methods associated with rational choice such as game theory, formal modeling and statistical analyses were not the dominant methods in the global discipline.[92] These methods were used in the US but other national IR communities were not adhering to the US’s preference and instead adopting methods of their choosing. Thereby leading one to question whether the US can be the intellectual core of IR if other methods are populating ‘core spaces’, such as American journals, American Political Science Departments etc.[93]

Methodological nationalism is this sense does not refer to the naturalization of a given unit, which in the case of IR would be the state.[94] Rather than referring to the assumption that the state is the natural organizing principle of study here methodological nationalism refers to the national methodological preferences of different IR communities. It seems that numerous IR communities have their own preferred means of studying IR. For example, Jonas Hagmann and Thomas Biersteker have argued that Europeans “tend to complement rational choice perspectives with reflexive and historical works, as opposed to the US schools, which complement those with formal theory and quantitative works”.[95] We can therefore infer that there is not just a transatlantic divide between the US and Europe, instead there are different methodological preferences within Europe. One only has to look at the trends within British IR, French IR, and Scandinavian IR to see the different methodological preferences operating.[96]

The methodological preferences found in different European countries also differ from the methodological trends found in other IR communities such as Australasia, Latin America and so on.[97] It appears that each IR community has its own methodological core, in other words a preferred and popular means of conducting inquiry into international relations.[98] Arguably, each IR community establishes a domestic methodological core and periphery, and then uses this domestic hierarchy to recognise, promote, and approve scholarship from other countries. Before one can map the specific geography of IR’s many methodological cores, more research is needed into the methodological preferences of particular IR communities, in order to explore how domestic hierarchies, emerge, and why certain ways of conducting inquiry have not travelled in the same way as certain concepts, language, and theories.

Nonetheless, using the intellectual core as a means of conceptualising the discipline we are asked to pay further attention to domestic hierarchies and their emergence and how dominant internal preferences set standards by which to view and judge domestic and international scholarly works. The intellectual gaze of the global discipline highlights that the core/periphery imaginary works in complicated and intersecting ways, producing stratifications and exclusions within both core and peripheral spaces, once again revealing ‘cores’ in places commonly understood to be ‘peripheries’.

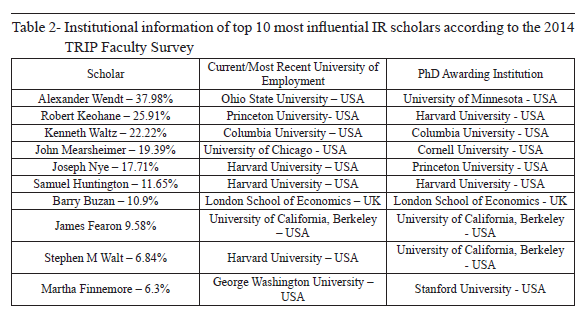

3.3. Institutional core

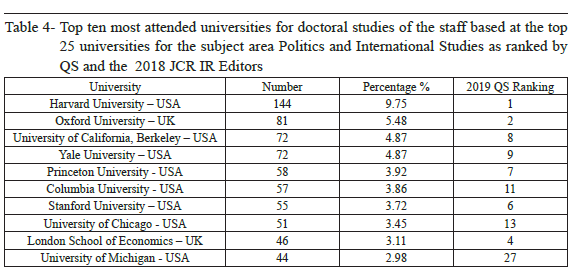

The institutional core of the discipline of IR is claimed to comprise the United States of America and the United Kingdom. This is due to these IR communities having the preeminent scholars, journals, university departments, professional associations etc.[99] This seeming British and American institutional core is reflected in the 2014 TRIP survey.[100] When asked to “list the four presses that publish books with the greatest influence on the way IR scholars think about international relations” the top 10 publication presses were all located in the US and UK.[101] In terms of the “five best PhD programmes in the world for a student who wants to pursue an academic career in IR?” the following universities were selected by the 2231 respondents; Harvard University (66.61%), Princeton University (47.96%), Stanford University (39.62%), Columbia University (32.77%), University of Oxford (27.16%), Yale University (25.68%), London School of Economics (23.67%), University of Chicago (19.09%), University of Cambridge (16.67%), and the University of California, Berkeley (13.94%).

A similar set of core US-UK institutions emerges when one looks at the institutional basis and PhD awarding institutions for key IR scholars. The 2014 TRIP faculty survey asked scholars to list which scholar’s work has had the greatest influence on the field of IR in the past 20 years.[102] Looking at where the top ten scholars are institutionally based and where they did their PhD’s table two shows that based on scholarly perceptions the disciplinary imaginary depicted in figure three seems to reflect this core-periphery dynamic.[103] However, if one explores the findings of metric based assessments – such as the QS University World Rankings - this imaginary does not reflect the one depicted in figure three, and suggests that the institutional core occupies a much larger geographical area, including spaces normally considered peripheral.

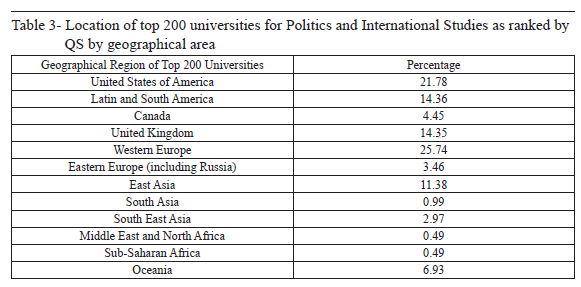

Coding the 2019 top 200 universities as ranked by QS for the subject area Politics and International Studies by geographical area[104] one can see that there are esteemed IR centres in universities outside of the US and UK. Table three shows that 63.87% of the highest ranked universities in the world for IR are located outside of the US and UK, with 34.14% in ‘non-Western’ countries. There are other institutions of IR, such as the discipline’s journals, that are also located outside of the West. Returning to table one, we see that there are a number (20.88%) of influential IR journals based in countries normally designated as ‘semi-peripheral’ or peripheral’.

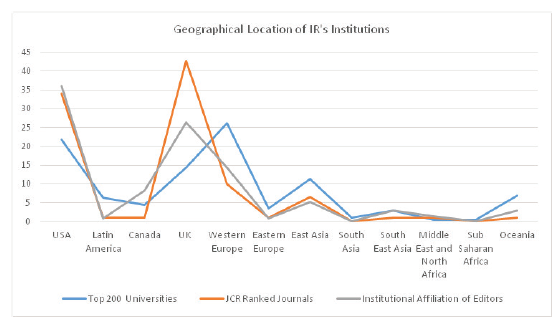

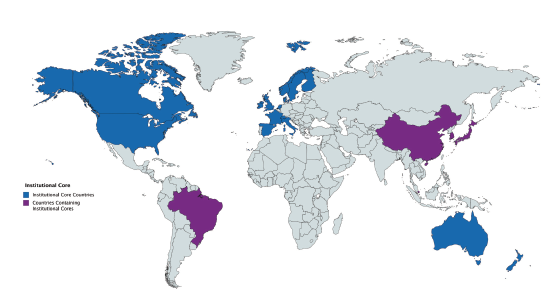

Given the influential role that journals have in shaping the field[105] in terms of making decisions about what is or isn’t published, the institutional affiliation of the scholars who oversee such assessments was explored in order to see where such significant scholars are based. The scholarly profiles of the Editor’s in Chief/Lead Editors for the 91 journals listed in the 2018 JCR were examined and their institutional location was coded using the previous geographical categories.[106] A total of 133 scholars were examined and their institutional affiliations is mapped in figure seven. A similar pattern emerges when one compares the different institutional locations of IR’s top universities, ranked journals and journal editors. Whilst the majority are located in the UK and US, a significant proportion are based in Western Europe, East Asia and Oceania as one can see in figure seven. This means that the core is larger than commonly depicted, it goes beyond the UK and US to include Australia, Canada, and Western Europe, with peripheries of the core in particular parts of East and South East Asia – or more specifically certain locations/universities within China, Japan, Singapore and South Korea.

Figure 7: Comparison of the geographical composition of IR’s Institutions

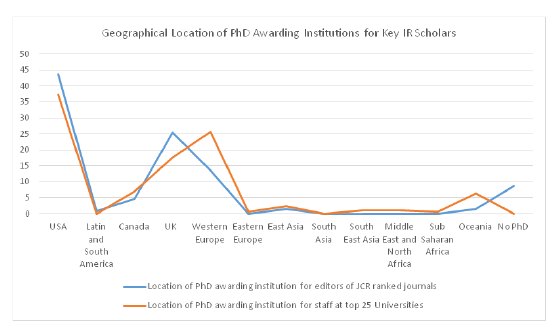

Viewing particular metrics of institutional success, the prestige of Australian, Canadian, East Asian, Latin and South American, South East Asian, and Western European universities and journals is clear. However, there is a gap between scholarly perceptions as demonstrated in the TRIP survey and such metrics. This gap prompted an exploration of scholarly choice, in terms of where particular scholars decided to undertake their doctoral research. Accounting for scholarly institutional decision making, revealed a slightly different institutional map of the discipline. In order to investigate the decisions of key IR scholars and therefore institutional figures, the biographical profile of the Editors in Chief/Lead Editors of the 91 journals listed in the 2018 JCR was investigated in order to determine where these scholars had conducted their doctoral research. Similarly, the biographical profiles of all permanent faculty/staff members of the top 25 Universities for Politics and International Studies as ranked by QS from 2016-2019 were investigated and the findings coded using the previous geographical categories.[107] The geographical location of the PhD awarding institution was noted for 133 journal editors and 1343 faculty members based at universities in Australia (3), Canada (1), East Asia (2), South East Asia (1), United Kingdom (5), United States of America (15), and Western Europe (3).[108]

Figure eight shows that the geographical profile is less diverse, and concentrated around a smaller set of countries. The most attended universities by the sample of scholars investigated were located in the US, UK and Western Europe. Whilst one cannot assume the reasons why these universities were selected (funding/scholarships offered, resources, location of supervisor, prestige, familial support etc.) the findings nonetheless do indicate the workings of a central institutional core in terms of universities with attractive and desirable doctoral programmes.

Figure 8: Comparison of the geographical composition of PhD Awarding institutions for certain IR scholars

The 1343 faculty members of the top 25 universities ranked by QS from 2016-2019 attended a total of 171 different universities for their doctorates. Not only was the overall geographical dispersal narrower when compared to figure seven, when looking at which universities were the most heavily attended a similar pattern to that represented in table two emerged. There was a particular set of universities (see table four) – the ‘centre of the core’ – that were the most heavily attended, and these universities occupy a particular geographical space in the US and UK.

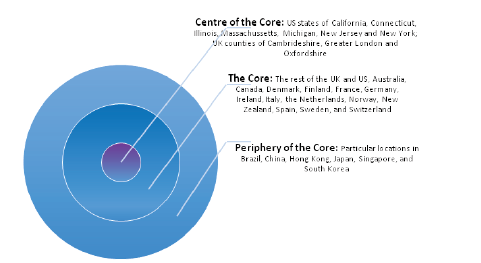

Tables two and four highlight the inner workings of the institutional core. Whilst the overall institutional core is geographically more encompassing than just the UK and US as commonly perceived, the ‘centre of the core’ constitutes a small group of universities located in the UK near London, and in the East and West coasts of the US. The institutional ‘centre of the core’ occupies a similar geographical terrain as the depiction given by Peter Marcus Kristensen.[109] Through using citation patterns to locate the institutional core of IR, Kristensen notes that the centre of the core is comprised of certain universities in “California, New York, Massachusetts, Illinois, Texas, New Jersey and Washington DC”.[110] The results from this brief inquiry show that there is an elite set of institutions that rank highly in both metrics and scholarly perceptions. The prestige and the possibilities of career advancement due to the reputations of such institutions further encourages students to attend these institutions to undertake their doctoral studies. This reinforces the high esteem of such institutions and embeds a self-reaffirming cycle that maintains the working and position of ‘the centre of the core’, which occupies particular locations within the United States and the United Kingdom.

Figure 9: Stratification of IR’s Institutional Core

Figure 10: IR’s Institutional Core

This section has looked at publication presses, journal editors, institutional choices of key scholars, and university rankings to reveal the stratification of the institutional core of IR. There are other institutions of IR such as professional associations, conferences, citation networks, and university syllabi that have not been examined here. However, existing studies into such institutions[111] reveal a similar set of institutional hierarchies as presented here, which help support the argument that the institutional core simultaneously occupies both a wider and narrower geographical space than commonly perceived (as figures nine and ten show). Meaning there are different core/periphery institutional geographies due to the stratification of power relations and therefore the workings of the core/periphery is much more complex and intersecting than commonly depicted. It is important to reveal the different power dynamics so that they can be further investigated and challenged. We need to ensure that the accompanying exclusionary mechanisms, hierarchies and institutional pressures will not go unchecked and that particular institutional barriers to scholars can be problematized.

4. The Implications of the Core/Periphery Imaginary

This article has clearly demonstrated that the discipline of IR has a series of different cores that occupy different geographical spaces (see figures five, six and ten). If one seeks to locate the ‘core’ in IR, then one needs to first delineate the specific ‘core’ one is looking for (linguistic, intellectual, institutional etc.), and secondly acknowledge the various stratifications and existence of ‘peripheries of the core’. Resultantly this means that the boundaries of the core and periphery are in flux and there are different core/peripheries occupying very different geographical spaces. As such, one can question the analytical value of this popular disciplinary imaginary due to its shifting dimensions. Through showing the stratification of IR’s different cores and revealing the workings of the core in spaces normally considered peripheral the core/periphery binary has been destabilized, and therefore its continued use requires a more nuanced application. However, even if one were to adopt the label and use it in a more refined and reflective manner, the function of employing the terms would continue to have similar disciplinary effects.

Signifying an IR community as belonging to the core or the periphery unifies, and homogenizes those within both sides of the dichotomy as the designation awards each community with a certain set of properties based on the conceptualization of the ‘core’ in use. The result of this homogenization is that the often-diverse tendencies and stratified power relations within the ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ are ignored in order to give the terms categorical and visual functions. This means that a somewhat false image of equality, access and mobility is produced, as the terms focus on the power relations between the core and periphery, thereby overlooking the asymmetries within each category. Consequently, both core and peripheral scholars are disciplined within each space.

Furthermore, when a country is labeled as a peripheral it not only becomes subordinated it also becomes depicted as consumptive and/or passive. Those who use the core/periphery relationship tend do so to highlight that there are few producers and many consumers of IR,[112] this results in an uneven configuration of knowledge flows from the center to the margins and the establishment of exclusionary mechanisms.[113] In each of the different workings of the core (linguistic, intellectual, institutional) the conventional wisdom depicts the core being the producer/center of knowledge[114] and the periphery as the consumptive, dependent relation rather than the resistant ‘other’.[115] Images of dependency have led to claims that peripheral scholarship is 'nothing other than what is has been taught',[116] it is simply a replication of core research, thereby lacking agency. When one challenges the asymmetry of power within IR and uses the terms core/periphery to help demonstrate/critique dominant and authoritative trends, one actually reinforces negative images of the periphery. As Audrey Alejandro claims, the use of such terms unfortunately “performs the self-same hierarchical and exclusionary system it denounces”.[117]

Recently there have been studies into 'peripheral scholarship' to break these depictions.[118] Efforts have focused on detailing the novel theoretical efforts underway, and highlighting the different ways IR is studied and practiced.[119] However, such research is often done with 1) reference to the undisturbed core, thereby reifying the marginal position of ‘peripheral’ scholarship; 2) without addressing the ways in which the periphery may already be shaping the core; or 3) acknowledging that areas of the periphery may actually be peripheries of the core. The premise behind much research, as outlined above, is that knowledge flows in a unidirectional manner. Therefore, even if the periphery is presented as generating new modes of practicing, teaching, theorizing IR for example, the assumption is that by very nature of its peripheral position it will not impact upon the core and is passive, thereby unifying scholars within again and overlooking the motives and agential decisions of such scholars.

Acknowledging the different cores, helps prevent a degree of homogenization but it still subsumes difference within these realms and therefore can help to promote erroneous disciplinary images that have disciplinary effects. By focusing on points of commonality to make categories work, we overlook differences. We can be at risk of presenting homogenous images of scholars within certain regions, which may unintentionally reinforce the asymmetrical power relations that were the very object of critique. This is due to sites of disciplinary power going unchecked. A focus on the core/periphery and therefore unifying those within the periphery through their shared marginal status means we overlook diversity, especially a diversity of production and a diversity of power relations within the periphery. We also overlook a series of exclusionary mechanisms within the periphery and the marginalization of ‘peripheral scholars’ by ‘peripheral scholars’.

The main aim of this article has been to challenge the existing use of the terms core and periphery in IR and to draw attention to the stratification of power within states, so that particular sites of disciplinary power are challenged. We need to expand our imaginary of the core/periphery beyond nation states to look at hierarchies within countries and therefore the extensive reach of the ‘core’. We need to critically examine the specific workings of the core in the ‘peripheries of the core’ that exist in ‘non-Western’ spaces so as to challenge existing mechanisms that further marginalize scholarship within these locations. We need to look at whether scholars are encouraged/persuaded to adopt ‘centre of the core’ traits and/or whether this is an agential decision taken to resist and challenge existing power relations, resulting in recognition and exchange.[120]

5. Conclusion

In locating IR’s different cores and the corresponding hidden geographies, this article has attempted to destabilize the core-periphery distinction ultimately in order to move beyond this disciplinary and disciplining archetype. Because of the implications of this dichotomy, whilst this article may draw attention to a more complex working of disciplinary power, and work to establish agency and recognition for ‘hidden cores’, the continued use of the core/periphery archetype risks the trap of essentialism. In blurring the distinctions between the two categories, and revealing hidden mechanisms and workings of disciplinary power, the overarching argument is for the discipline to collapse the use of this particular disciplinary boundary in order to prevent homogenizing exclusions.

In highlighting the changing geographies of the core-periphery and thereby drawing attention to the operation of other epistemic hierarchies, I do not mean to erase the overarching inequalities of power in the global discipline of IR. Asymmetry remains, and the workings of the centre of the core presents scholars outside of this space with a series of difficult realities and decisions. For instance, decisions about which language to write in, where to study, where to publish, and whether to take the risk and develop IR theory.[121] It is because of the existing asymmetry of power in IR that we need to be careful about the terms we use to depict the unequal distribution of power to ensure that these do not have ‘counter-productive’[122] consequences, such as homogenisation, removal of agency/recognition and working to make invisible the construction of epistemic hierarchies within states. We need to ensure that the terms we use allow us to fully examine the reach of disciplinary power and in turn explore how academic elites are able to construct additional barriers for scholars and exclude particular forms of knowledge.[123] As such, there is a need to look at the workings of particular hierarchies within certain commonly perceived ‘peripheral’ spaces and to challenge these as well as the larger global asymmetries of power.

Appendix

Code |

Geographical Region |

0 |

United States of America |

1 |

Latin and South America (including the Caribbean) |

2 |

Canada (including Greenland) |

3 |

United Kingdom |

4 |

Western Europe |

5 |

Eastern Europe (including Russia) |

6 |

East Asia |

7 |

South Asia |

8 |

South East Asia |

9 |

Middle East and North Africa |

10 |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

11 |

Oceania |

The categories include the following countries:

United States of America: Puerto Rico, and the United States of America

Latin and South America: Antigua, Argentina, Aruba, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Cayman Islands, Chile, Columbia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Grenada, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Martinique, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, St. Kitts & Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent & the Grenadines, Trinidad & Tobago, Uruguay, Venezuela.

Canada: Canada and Greenland.

United Kingdom: England, Northern Island, Scotland and Wales.

Western Europe: Andorra, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Canary Islands (Spain), Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, San Marino, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Vatican City.

Eastern Europe: Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan

East Asia: China, Hong Kong, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, Taiwan, Tibet

South Asia: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka

South East Asia: Brunei, Cambodia, East Timor, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam

Middle East and North Africa: Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Morocco (incl. Western Sahara), Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey (incl. Turkish Cyprus), United Arab Emirates (Abu Dhabi, Dubai, etc.), Yemen.

Sub-Saharan Africa: Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros Islands, Cote d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast), Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea- Bissau, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Sao Tome & Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

Oceania: Australia, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, French Polynesia, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, New Zealand, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu.

2: Breakdown of the top 25 Universities as Ranked by QS for Politics and International Studies: From 2019-2016 the top 25 Universities as ranked by QS were noted and the current biographical profiles of the staff at these institutions was investigated. The profiles of permanent and full time members of staff were explored, this meant that Emeritus, Teaching Assistants and part-time Research Associates were not included.

The breakdown is as follows:

| Ranking | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 |

| 1 | Harvard University | Harvard University | Harvard University | Harvard University |

| 2 | University of Oxford | University of Oxford | University of Oxford | University of Oxford |

| 3 | Sciences Po | Princeton University | London School of Economics | London School of Economics |

| 4 | London School of Economics | Sciences Po | Sciences Po | Sciences Po |

| 5 | University of Cambridge | London School of Economics | University of Cambridge | University of Cambridge |

| 6 | Stanford University | University of Cambridge | The Australian National University | Yale University |

| 7 | Princeton University | Yale University | Yale University | Stanford University |

| 8 | University of California, Berkeley | The Australian National University | Princeton University | The Australian National University |

| 9 | Yale University | University of California, Berkeley | University of California, Berkeley | Princeton University |

| 10 | The Australian National University | Columbia University | Columbia University | University of California, Berkeley |

| 11 | Columbia University | Georgetown University | Georgetown University | Georgetown University |

| 12 | National University of Singapore | National University of Singapore | University of Toronto | Columbia University |

| 13 | University of Chicago | University of Chicago | University of Chicago | National University of Singapore |

| 14 | University of California, Los Angeles | University of Toronto | University of California, Los Angeles | University of Chicago |

| 15 | Georgetown University | The University of Tokyo | National University of Singapore | University of California, Los Angeles |

| 16 | University of California, San Diego | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | Johns Hopkins University | Johns Hopkins University |

| 17 | The University of Hong Kong | Stanford University | Freie Universitaet Berlin | New York University |

| 18 | King’s College London | The University of Sydney | The University of Tokyo | Freie Universitaet Berlin |

| 19 | Freie Universitaet Berlin | University of California, Los Angeles | Cornell University | The University of Tokyo |

| 20 | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | Freie Universitaet Berlin | Stanford University | Cornell University |

| 21 | University of Toronto | University of California, San Diego | New York University | Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| 22 | The University of Sydney | Johns Hopkins University | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | University of California, San Diego |

| 23 | SOAS University of London | SOAS University of London | The University of Sydney | The University of Hong Kong |

| 24 | The University of Tokyo | George Washington University | University of California, San Diego | The University of Toronto |

| 25 | The University of Melbourne | The University of Hong Kong | University of Copenhagen | Leiden University |

The highlighted universities above are those that did not appear in the rankings for four consecutive years. However, many of the highlighted universities appeared twice or more. The only universities that feature once in the rankings from 2019-2016 are; The University of Melbourne, University of Copenhagen and Leiden University.

Looking at the above universities by geographical location the breakdown is:

| Geographical Region | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | Total | Percentage |

| United States of America | 11 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 52 | 52% |

| Canada (including Greenland) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4% |

| United Kingdom | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 15 | 15% |

| Western Europe | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 10% |

| East Asia | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 7% |

| South East Asia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4% |

| Australia | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 8% |

Acharya, Amitav. “Advancing Global IR: Challenges, Contentions and Contributions.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 4–15.

–––. “Dialogue and Discovery: In Search of International Relations Theories Beyond the West.” Millennium 39, no. 3 (2011): 619–37.

–––. “Theorising the International Relations of Asia: Necessity of Indulgence? Some Reflections.” The Pacific Review 30, no. 6 (2017): 816–28.

Acharya, Amitav, and Barry Buzan. “Why is There No Non-Western International Relations Theory? An introduction.” International Relations of the Asia Pacific 7, no. 3 (2007): 287–312.

–––. “Why is There non Non-Western IR Theory? Ten Years On.” International Relations of the Asia Pacific 17, no. 3 (2017): 341–70.

Adamson, Fiona B. “Spaces of Global Security: Beyond Methodological Nationalism.” Journal of Global Security Studies 1, no. 1 (2016): 19-35.

Adiong, Nassef Manabilang, Raffaele Mauriello, and Deina Abdelkader, eds. Islam in International Relations: Politics and Paradigms. Oxon: Routledge, 2018.

Alagappa, Muthiah. “International Relations Studies in Asia: Distinctive Trajectories.” International Relations of the Pacific 11, no. 2 (2011): 193–230.

Alejandro, Audrey. “The Narrative of Academic Dominance: How to Overcome Performing the ‘Core-Periphery’ Divide.” International Studies Review 19, no. 2 (2017): 300–04.

–––. Western Dominance in International Relations? The Internationalisation of IR in Brazil and India. Oxon: Routledge, 2019.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Gonca Biltekin. “Widening the World of IR: A Typology of Homegrown Theorising.” All Azimuth 7, no. 1 (2018): 45–68.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Gonca Biltekin, eds. Widening the World of International Relations: Homegrown Theorising. Oxon: Routledge, 2018.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Julie Mathews. “Are the Core and the Periphery Irreconcilable? The Curious World of Publishing in Contemporary International Relations.” International Studies Perspectives 1, no. 3 (2000): 289–303.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Julie Mathews. “Periphery Theorising for a Truly Internationalised Discipline: Spinning IR Theory Out of Anatolia.” Review of International Studies 34, no. 4 (2008): 693–712.

Behera, Navnita Chadha. “Re-Imaging in India.” International Relations of the Asia Pacific 7, no. 3 (2007): 341–68.

–––. “South Asia: A ‘Realist’ Past and Alternative Futures.” In IR Scholarship Around the World: Worlding Beyond the West, edited by Arlene Tickner, and Ole Wæver, 137–57. Oxon: Routledge, 2009.

Biersteker, Thomas. “The Parochialism of Hegemony: Challenges for ‘American’ International Relations.” In IR Scholarship Around the World: Worlding Beyond the West, edited by Arlene B. Tickner and Ole Wæver, 308–27. Oxon: Routledge, 2009.

Bilgin, Pinar. “Contrapuntal Reading” as a Method, an Ethos, and a Metaphor for Global IR.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 134–46.

–––. “Thinking Past ‘Western’ IR?” Third World Quarterly 29, no. 1 (2008): 5–23.

Bond, David. “Thomson Reuters in $3.55bn sale of IP and science business.” Financial Times, July 11, 2016. Accessed June 2, 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/81697af2-4778-11e6-8d68-72e9211e86ab.

Buzan, Barry. “Could IR Be Different?” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 155–57.

Cardoso, Fernando, and Enzo Faletto. Dependency and Development in Latin America. California: University of California Press, 1979.

Chatterjee, S Shibashis. “Western Theories and the non-Western World: A Search for Relevance.” South Asian Survey 21, no. 1&2 (2017): 1–19.

Chen, Ching-Chang. “The Absence of Non-Western International Relations Theory in Asia Reconsidered.” International Relations of the Asia Pacific 11, no. 1 (2011): 1–23.

Choi, Jong Kun. “Theorizing East Asian International Relations in Korea.” Asian Perspective 32, no. 1 (2008): 193–216.

Connell, Raewyn. Southern Theory: Social Science and the Global Dynamics of Knowledge. Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2007.

Cox, Wayne, and Kim Richard Nossal. “The ‘Crimson World’: The Anglo Core, the Post-Imperial Non-Core, and the Hegemony of American IR.” In IR Scholarship Around the World: Worlding Beyond the West, edited by Arlene B. Tickner and Ole Wæver, 287–307. Oxon: Routledge, 2009.

D’Aoust, Anne-Marie. “Accounting for the Politics of Language in the Sociology of IR.” Journal of International Relations and Development 15, no. 1 (2012): 120–31.

Deciancio, Melissa. “International Relations for the South: A Regional Research Agenda for Global IR.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 106–99.

Duszak, Anna, and Jo Lewkowicz. “Publishing academic texts in English: A Polish Perspective.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 7, no. 2 (2008): 108–20..

Escudé, Carlos. “Argentina's Grand Strategy in Times of Hegemonic Transition: China, Peripheral Realism and Military Imports.” Revista De Relaciones Internacionales, Estrategia y Seguridad 10, no/ 1 (2015): 21–39.

–––. “Realism in the Periphery.” In Routledge Handbook of Latin America in the World, edited by J. Dominguez and A. Covarrubias, 45–57. Oxon: Routledge, 2014.

Eun, Yong-Soo, and Kamila Pieczara. “Getting Asia Right and Advancing the Field of IR.” Political Studies Review 11, no. 3 (2013): 369–77.

Ferguson, Yale. “The Transatlantic Tennis Match in IR Theory: Personal Reflections.” European Review of International Studies 1, no. 1 (2014): 8–24.

Friedrichs, Jörg. European Approaches to International Relations Theory: A House with Many Mansions. London: Routledge, 2004.

Friedrichs, Jörg, and Ole Wæver. “Western Europe: Structure and Strategy at the National and Regional Levels.” In IR Scholarship Around the World: Worlding Beyond the West, edited by Arlene B. Tickner and Ole Wæver, 261–86. Oxon: Routledge, 2009.

Galtung, Johan. “A Structural Theory of Imperialism.” Journal of Peace Research 8, no. 2 (1971): 81–117.

Garfield, Eugene. “How the ISI Selects Journals for Coverage: Quantitative and Qualitative Considerations.” Current Contents 22 (1990):185–93.

Giesen, Klaus-Gerd. “France and Other French-Speaking Countries 1945-1994.” In International Relations in Europe: Traditions, Perspectives and Destinations, edited by Knud Erik Jørgensen, and Tonny Brems Knudsen, 72-99. Oxon: Routledge, 2006.

Grenier, Felix, and Jonas Hagmann. “Sites of Knowledge (Re)Production: Toward an Institutional Sociology of IR Scholarship.” International Studies Review 18, no. 2 (2016): 333–65.

Grondin, David. “Languages as Institutions of Power/Knowledge in Canadian Critical Security Studies: a personal tale of an insider/outsider.” Critical Studies on Security 2, no. 1 (2014): 39–58.

Hagmann, Jonas, and Thomas J. Biersteker. “Beyond the Published Discipline: Toward a Critical Pedagogy of International Studies.” European Journal of International Relations 20, no. 2 (2014): 291–315.

Hamel, Rainer E. “The Dominance of English in the International Scientific Periodical Literature and the Future of Language Use in Science.” AILA Review 20 (2007): 53–71.

Hellmann, Gunther. “Methodological Transnationalism – Europe’s Offering to Global IR.” European Review of International Studies 1, no. 1 (2014): 25–37.

Holsti, Kal. The Dividing Discipline: Hegemony and Diversity in International Theory. London: Allen & Unwin, 1985.

Hurrell, Andrew. “Towards the Global Study of International Relations.” Revista Brasileira de Politica Internacional 58, no. 2 (2016): 1–18.

Hutchingson, Kim. “Dialogue between Whom? The Role of the West/Non-West Distinction in Promoting Global Dialogue in IR.” Millennium 39, no. 3 (2011): 639–47.

Jenkins, Katy. “Exploring Hierarchies of Knowledge in Peru: Scaling Urban Grassroots Women Health Promoters’ Expertise.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 41, no. 4 (2009): 879–95.

Jørgensen, Knud Erik. “After Hegemony in International Relations, or, the Persistent Myth of American Disciplinary Hegemony.” European Review of International Studies 1, no. 1 (2014): 57–64.

–––. “Continental IR Theory: The Best Kept Secret.” European Journal of International Relations 6. No. 9 (2000): 9–42.

Jørgensen, Knud Erik, Audrey Alejandro, Alexander Reichwein, Felix Rösch, and Helen Louise Turton. Reappraising European IR Theoretical Traditions. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Jørgensen, Knud Erik, and Tonny Brems Knudsen, eds. International Relations in Europe: Traditions, Perspectives and Destinations. Oxon: Routledge, 2006.

Kayaoglu, Turan. “Westphalian Eurocentrism in International Relations Theory.” International Studies Review 12, no. 2 (2010): 193–217.

Kojo, Yoshiko. “Global Issues and Business in International Relations: Intellectual Property Rights and Access to Medicines.” International Relations of the Asia Pacific 18, no. 1 (2018): 5–23.

Kristensen, Peter Marcus. “Dividing Discipline: Structures of Communication in International Relations.” International Studies Review 14, no. 1 (2012): 32–50.

–––. “International Relations in China and Europe: the Case for Interregional Dialogue in a Hegemonic Discipline.” The Pacific Review 28, no. 2 (2015): 161–87.

–––. “Navigating the Core-Periphery Structures of ‘Global’ IR: Dialogues and Audiences for the Chinese School as Traveling Theory.” In Constructing a Chinese School of International Relations: Ongoing Debates and Sociological Realities, edited by Yongjin Zhang and Teng-Chi Chang, 143–62. New York: Routledge, 2016.

–––. “Revisiting the "American Social Science" – Mapping the Geography of International Relations.” International Studies Perspectives 16, no. 3 (2015): 246–69.

Kubálkova, Vendulka. “The ‘Take-Off’ of the Czech IR Discipline.” Journal of International Relations and Development 12, no. 2 (2009): 205–20.

Kuru, Deniz. “Homegrown Theorizing: Knowledge, Scholars, Theory.” All Azimuth 7, no. 1 (2018): 69–86.

Lake, David. “Theory is Dead, Long Live Theory: The End of the Great Debates and the Rise of Eclecticism in International Relations.” European Journal of International International Relations 19, no. 3 (2013): 567–87.

Larivière Vincent, Stefanie Haustein and Philippe Mongeon. “The Oligopoly of Academic Publishers in the Digital Era.” PLOS ONE 10, no. 6 (2015): 1–15.

Lebedeva, Marina M. “International Relations Studies the USSR/Russia: Is there a Russian National School of IR Studies?” Global Society 18, no. 3 (2004): 263–78.

Makarychev, Andrey, and Viatcheslav Morozov. “Is ‘Non-Western Theory’ Possible? The Idea of Multipolarity and the Trap of Epistemological Relativism in Russian IR.” International Studies Review 15 no. 3 (2013): 328–50.

Maliniak, Daniel, Susan Peterson, Ryan Powers, and Michael J. Tierney. “TRIP 2014 Faculty Survey.” Williamsburg, VA: Institute for the Theory and Practice of International Relations, 2014. Accessed June 2, 2019. https://trip.wm.edu/charts/

Mallavarapu, Siddharth. “Development of International Relations Theory in India: Traditions, Contemporary Perspectives and Trajectories.” International Studies 46, no. 1-2 (2009): 165–83.

Mansbach, Richard. “Among the Very Best: A Brief Selection of European Contributors and Contributions to IR Theory.” European Review of International Studies 1, no. 1 (2014): 80–7.

Mansour, Imad. “A Global South Perspective on International Relations Theory.” International Studies Perspectives 18, no. 1 (2017): 2-3.

Mearsheimer, John. “Benign Hegemony.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 147–49.

Morgan, John. “Branching Out” The Times Higher Education, February 3, 2011. Accessed June 2, 2019. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/branching-out/415018.article

Moshirzadeh, Homeira. “Iranian Scholars and Theorizing International Relations: Achievements and Challenges.” All Azimuth 7, no. 1 (2018): 103–19.

Niang, Amy. “The imperative of African perspectives on International Relations (IR).” Politics 36, no. 4 (2016): 453–66.

Nossal, Kim Richard. “Tales That Textbooks Tell: Ethnocentricity and Diversity in American Introductions to International Relations.” In International Relations-Still an American Social Science? Toward Diversity in International Thought, edited by Robert M.A. Crawford and Darryl S.L. Jarvis, 167–86. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2001.

Odoom, Isaac, and Nathan Andrews. “What/Who is still Missing in International Relations Scholarship? Situating Africa as an Agent in IR Theorising.” Third World Quarterly 38, no. 1 (2017): 42–60.

Paasi, Anssi. “Globalisation, Academic Capitalism, and the Uneven Geographies of International Journal Publishing Space.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 35, no. 5 (2005): 769–89.

Puchala, Donald. “Some Non-Western Perspectives on International Relations.” Journal of Peace Research 34, no. 2 (1997): 129–34.

Rokkan, Stein, and Derek W. Urwin. Economy, Territory, Identity: Politics of West European Peripheries. London: Sage, 1983.

Shahi, Deepshikha. “Introducing Sufism to International Relations Theory: A Preliminary Inquiry into Ontological, Epistemological and Methodological Pathways.” European Journal of International International Relations 25, no. 1 (2019): 250–75.

Shahi, Deepshikha, and Gennaro Ascione. “Rethinking the Absence of Post-Western IR Theory in India: ‘Advancing Monism’ as an Alternative Epistemological Resource.” European Journal of International Relations 22, no. 2 (2016): 313–34.

Shambaugh, David. “International Relations Studies in China Today: History, Trends and Prospects.” International Relations of the Asia Pacific 11, no. 3 (2011): 339–72.

Shani, Giorgio. “Toward a Post-Western IR: The Umma, Khalsa Panth and Critical International Relations Theory.” International Studies Review 10, no. 4 (2008): 722–34.

Shilliam, Robbie, ed. International Relations and Non-Western Thought: Imperialism, Colonialism and Investigations of Global Modernity. Oxon: Routledge, 2011.

Smith, Karen. “Has Africa Got Anything to Say? African Contributions to the Theoretical Development of International Relations.” The Round Table 98, no. 402 (2009): 269–84.

–––. “Reshaping International Relations: Theoretical Innovations from Africa.” All Azimuth 8, no. 2 (2018): 81–92.

Smith, Steve. “The United States and the Discipline of International Relations: ‘Hegemonic Country, Hegemonic Discipline.’” International Studies Review 4, no. 2 (2002): 67–85.

Streitwieser, Bernhard, and Bradley Beecher. “Information Sharing in the Age of Hyper-competition: Opening an International Branch Campus.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning Learning 49, no. 6 (2017): 44–50.

Taylor, Lucy. “Decolonizing International Relations: Perspectives from Latin America.” International Studies Review 14, no. 3 (2012): 386–400.

Testa, James. “The Thomson Scientific Journal Selection Process.” Contributions to Science 4, no. 1 (2008): 69–73.

Tickner, Arlene. “Core, Periphery and (neo)Imperialist International Relations.” European Journal of International Relations 19, no. 3 (2013): 627–46.

–––. “Hearing Latin American Voices in International Relations Studies.” International Studies Perspectives 4, no. 4 (2008): 325–50.

Tickner, Arlene, and David Blaney, eds. Thinking International Relations Differently. Oxon: Routlegde, 2012.

Tingyang, Zhao. “A Political World Philosophy in terms of All-under-heaven (Tian-xia).” 56, no. 1 (2009): 5–18.

–––. “Redefining Political Concepts with Tianxia: Problems, Conditions and Methods.” World Economics and Politics 6 (2015): 4–22.

–––. The System of Tianxia – All-Under Heaven: A Philosophy of World Institutions. Nanjing: Jiangsu Education Publishing House, 2005.

Turton, Helen L. International Relations and American Dominance: A Diverse Discipline. Oxon Routledge, 2016.

Turton, Helen L., and Lucas Freire. “Peripheral Possibilities: Revealing Originality and Encouraging Dialogue through a Reconsideration of ‘Marginal’ IR Scholarship.” Journal of International Relations and Development 19, no. 4 (2016): 534–57.

Uzuner, Sedef. “Multilingual Scholar’s Participation in Core/Global Academic Communities: A literature review.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 7 (2008): 250–63.

Vasilaki, Rosa. “Provincialising IR? Deadlocks and Prospects in Post-Western IR Theory.” Millennium 41, no. 1 (2012): 3–22.