Mehmet Akif Okur

Yildiz Technical University

Cavit Emre Aytekin

Kafkas University

This study examines the usage of non-Western theories in research and education by International Relations (IR) scholars in Turkey. Our primary purpose is to understand the level of engagement with the non-Western IR debate, with its prospects and variations, in Turkish academia, and to evaluate the familiarity of Turkish IR scholars from different schools with non-Western IR theories. Relevant data were obtained from a questionnaire with 47 items designed to let participants, consisting of 116 academicians at IR departments from 57 Turkish Universities, provide their teaching experiences, views, and perceptions concerning non-Western IR Theory. While our findings based on this data confirm the literature on the scarcity of non-Western theories in Turkish IR scholarship, we have also furthered it with many details. Firstly, according to the findings, respondents who study and teach IR Theory at Turkish universities think that the IR theories of Western origin dominating the literature are not universal or objective in terms of their function as interpreters of IR issues. But interestingly, those considerations direct scholars to Western critical IR Theory schools rather than non-Western theories. The other key conclusion of this study confirms our expectations. The thoughts, concepts and theories emanating from the Turkish-Islamic world have much more recognition than other non-Western IR theories among Turkish IR scholars.

1. Introduction

In the context of International Relations Theory (IR Theory), a debate continues on the distribution of knowledge production in line with the power imparities, civilizational fault lines, intellectual disintegration, and interactions between parties of these divisions. In relation to this, intellectual and philosophical deliberations that have been developed and accumulated over the years on the political nature of knowledge are garnering increasingly more attention. Ideas about the relational character of power and theory production, which constitute a part of the fourth great debate in IR, are well-known. The birth and formation of IR as a highly American social science is now being made explicit in the context of calls for non-Western/Global IR Theory. We have strong and widely accepted comments from prominent figures of the discipline that reveal different dimensions of the issue.[1]

The discussion on the division of Western and non-Western Theory is a candidate to be the new theoretical divergence point of IR.[2] In order to examine the hierarchical character of the discipline between core and periphery, behavioral measures such as the geographical distribution of scholars who can publish in theoretical journals,[3] citation networks, bibliometric situations,[4] PhD degrees from foreign countries,[5] resource material selections[6] for the curricula and syllabi,[7] and individual perceptions of academics toward the core-periphery debate in the discipline[8] have been used.

Turkish academia enjoys a dynamic and prolific community of IR scholars. Although it resembles the discipline's dominant epistemic community, there is no doubt that Turkish academics are interested in the non-Western IR Theory debate. In this study, we wish to concentrate on this topic, which has received scant attention. It would be of interest to know whether Turkish academia has an inclination toward non-Western Theory. Our primary objective is to assess the familiarity of Turkish IR scholars with various non-Western IR theories as well as the debates surrounding them.

The article pursues a detailed account of Turkish scholarship regarding IR Theory to understand how and to what extent non-Western IR theories, concepts, and theorists are utilised. We sought to assess how the Western/non-Western/post-Western debates impact Turkish IR Theory teaching and research activities in light of the large and voluminous accumulation produced to date. We developed a questionnaire based on practical and epistemological themes relevant to the subject of non-Western IR theories. Our questions were intended to provide data for evaluating perceptions of the objectivity, universality, and value-relevancy of IR theories in the survey, the details of which will be explained in the methodology section. Beyond that, we want to find out which non-Western theories are more commonly referenced. To achieve such an outcome, we separate non-Western ideas into three sub-sections: Asian-based (or originated) theories, African-Latin American-based theories, and Turkish-Islamic World-based theories.

Based on the data gathered from our survey, this article combines two investigations: First, the article aims to explore Turkish academia's stance toward IR theories and the degree of its interest in the non-Western IR Theory debate. Second, the article strives to pinpoint where this interest originates from and what the fluctuating tendencies toward non-Western IR theories are. By addressing the relevant questions, we want to contribute to the understanding of this understudied topic. To accomplish that goal, we will present a general literature review on non-Western IR Theory in the following part of the text. After outlining our data-gathering methodology, we will reveal any correlations between answers to our questions by displaying them in charts. The variations in participants' views toward mainstream theories, their meta-theoretical and epistemological assessments of the nature of theories, and interest in non-Western theories classified by their geographical/civilizational origins will also be examined in this evaluation process.

2. An Outlook on the Non-Western Theory Debate

Opinions about US or Western dominance in the discipline, which seem to have become so widespread as to resemble the debates that built the grand narrative of IR, bring about questions regarding the value of mainstream IR theories in geographies that do not contribute to their production. In the words of Bilgin and Çapan, the discipline that has become today's social science through globalization starting in the 1950s was essentially regional IR. Criticism from the 2010s that academics outside of North America and Western Europe are not adequately represented in publications and curricula is a result of the globalization of knowledge once produced for a specific region.[9] However, realizing the inadequacy of the existing literature on theories[10] is a typical motivation to search for new theories. The unearthed inefficiency of the mainstream in the face of new developments can be shown as a distinct reason for the need to have non-Western theorization.[11] It is possible to come across, for example, remarks stating that if these theories were produced in the West, then they are for the West, as indicated by the Coxian interpretation of theory. [12]

Cox clearly expresses that he has spatial identity formations like civilizations in mind while thinking about the effects that theoretical debates and theory production processes have on world politics. The following quotation is from his latest book:[13]

My scholarly objective was to try to understand the forces that were shaping the world’s future in the early decades of the 21st century and the potential for compatibility and for conflict amongst them. This led me to focus on civilizations as the constituent entities of the world. Civilizations were ways of being that combined and integrated social, cultural, political and economic aspects of life, each of them active in the making of the future… ...My object was rather to understand better how people in different human communities came to understand the world which they perceived around them, what stimulated their acceptance or rejection of aspects of that world, and what might arouse in them a determination to do something about it.

Cox rejects the fixation of identities in a permanent conflictual movement as described in the Clash of Civilizations thesis, but he also clearly accepts that civilizational identities affect ways of thinking. Furthermore, civilizations have their respective territories, although people who once socialized in a certain civilizational zone can change their area of settlement to the territory of another civilization and even attempt to self-assimilate themselves there.

This is adaptive critical inference, implying that different geographies can add different characteristics to theory.[14] The basis of non-Western Theory is that key mainstream concepts take Western history as a reference point.[15] Suggestions for alternatives to the Western historical narrative are also within this scope. To broaden the framework here, a convergence is perceived between the emphasis on flaws caused by the dominance of Western Theory and the acceptance of problems in the literature based on the Eurocentric perspective prevailing in political history narratives. This reasoning is important for our research, as we also aim to explore perspectives on the position of postmodern, postcolonial, and critical theories with origins in the vast literature of Eurocentrism because one of the contested issues in the non-Western IR Theory literature is the contribution of these critical theories to the construction of non-Western theories.[16] Calls for the need to globalize IR by providing intellectual diversity are, in a way, an extension of the post-positivist approaches of the last 20 years.[17]

The current state of this debate on the geographical and, therefore, political nature of IR Theory production is manifested in the invitation for inclusion of non-Western voices. Now, not only criticism of Western domination, but also proposals regarding the exploration and building of alternative approaches are well known to the academic community.[18] We already have a sizable literature dedicated to discussing and revealing that mainstream IR Theory has its origins in the history of Western thought. The well-known lack of non-Western theories in the discipline’s core is attributed to reasons such as ignorance and isolation, academic network concerns, or lack of necessity.[19] Regardless of all that, given that different life experiences can change certain assumptions, as David A. Lake has said,[20] the call of Acharya and his followers is to propose Global IR as a framework to overcome these constraints.[21] Not presented as a stand-alone theory, Global IR is a framework challenging the supremacy of Western-dominated theoretical research,[22] although it can be seen as another medium for integration of peripheral academia into the Western core because of the unbalanced and unsatisfactory practical results of this approach. The stated objective was to become a platform for creating new theories beyond criticism of Western domination in the literature. This platform, in Acharya's own words, is an effort to overcome the singularity of universality through the perspectives of world history and regional integration, in line with the goal of pluralistic universality.[23] But the results of this mission thus far have not appeased critics complaining of the ongoing supremacy of Western institutions and perspectives even though they are now called global, not Western.

It can be expected that the role of non-Western actors in the production of knowledge and theory will rise in line with the processes increasing their share in the construction of ontological reality that was once monopolized by mainstream IR Theory.[24] One of the important arguments of the non-Western Theory debate is that Western dominance in the discipline bears on the power relations in international politics.[25] In line with this logic, it is reasonable to draw attention to the relationship between theory, state interest, and politics. The assertion that IR Theory should represent humanity more largely stems from intense philosophical and empirical study underlining the knowledge/power/geography interaction. Following this reasoning, efforts to evaluate the current US or Western-dominated IR discipline through the perspective of a critical sociology of science, propose new concepts and theories, and observe non-Western production through empirical studies will serve this process.

3. Diagnosis of Turkish IR Scholarship in the Context of non-Western Theory

Our research provides new empirical data shedding light on the debate that aims to shape IR studies from local angles by investigating the relevance of non-Western IR Theory studies in Turkish academia. We question how this debate in the worldwide scholarly community of IR is reflected in Turkish IR scholarship. IR scholars in Turkey are largely a part of the epistemic community of Western IR in terms of many parameters. TRIP (Teaching, Research, and International Policy) studies, which successfully describe IR's identities and structures in different geographies, also indicate this reality.[26] However, non-Western Theory, homegrown theory building, and Global IR debates are still among the emerging interests of the Turkish IR community.

We have gathered an important impression from TRIP surveys about the influence of IR Theory study and non-Western theories in Turkish IR academia.[27] Comprehensive interpretations can be made from these data regarding the development, current situation, basic features, and position of Turkish scholars in the worldwide IR community. For example, we know that there is a strong balance in Turkish academia between those who see themselves as part of the global, regional, and local networks. Global IR studies based on Wemheuer-Vogelaar and Bell's 2014 TRIP data come to similar conclusions.[28] But it does not contain a theory or concept that can be directly defined as or associated with non-Western Theory, and so what it measures is the rate at which both Western and non-Western scholars use existing mainstream epistemology and paradigms.

It is noteworthy that in Wemheuer-Vogelaar’s survey, there was no significant difference between the numbers of participants who stated that they did Western theoretical studies and those who did Non-Western ones.[29] However, despite this result, we draw attention to the fact that theoretical studies can have different forms and meanings, and we think that these differences should be measured separately on the basis of civilizational identities. IR communities in the non-Western world may differ on what it means to theorize or do a theoretical study. Considering that the non-Western world is perceived by the core as a place where theories are tested, distinguishing which type of theoretical work is more common in those peripheral academic communities is necessary.[30]

Thus, we aim to reveal the issues that are not included in the TRIP surveys, which are the largest sources that shed light on the disciplinary and theoretical tendencies of Turkish IR academia. In the comprehensive pool of TRIP data, knowledge about the debate on non-Western IR Theory is incomplete, especially since non-Western theories, concepts, and names are not directly involved. In this sense, our study is an effort to produce pioneering data containing these parameters.

4. Research Design and Methodology

The main purpose of our study is to make a detailed account of Turkish IR scholarship so that we can see its considerations regarding the universality and objectivity of the IR Theory curriculum. In this vein, the ways in which Turkish scholars incorporate theory into other IR courses, and the extent to which they use various non-Western IR theories, will also be explored. During this exploration, we will try to show how and to what degree non-Western IR theories, concepts, and theorists are referenced. In light of the voluminous data accumulated thus far, we tried to evaluate how the teaching and research activities conducted by Turkish scholars in the field of IR Theory are affected by the Western/Non-Western/Post-West debates.

While the term “Western” points to a concrete geography, especially in the axis of the USA and Europe, the term “non-Western” takes the form of an "all-encompassing" and unlimited phenomenon. In fact, it is quite possible to refer to categorizations based on different aspects, such as geographic/civilizational distinctions outside of the West. In this research study, we try to demonstrate this phenomenon in the context of IR scholarship in Turkey. While we take “non-Western” as a general category, we additionally divide it into sub-sections. Thus, we will see whether there is a difference between possible sub-units of non-Western theories, reflected in theoretical and pedagogical tendencies and perceptions. We divided non-Western theories according to sub-geographical or civilizational/cultural categories: Asian-based (or originated) theories, African-Latin American-based theories, and Turkish-Islamic World-based theories. In that triple division, theories of Asian origin correspond to the local theorizing efforts of Asian countries such as China, India, Japan, and Korea,[31] the theories of African-Latin American origin refer to the equivalent of the same such efforts in Africa and Latin America, and theories originating from the Turkish-Islamic tradition of thought are used in reference to the philosophical concepts, thoughts, and approaches arising from the historical geography of the Turkic or Islamic World.

The above categorizations are inspired not only by their civilizational identification. Convergences in the literature, geographical reference points, and familiarity with Turkish academia influenced their determinations. Theories of Asian origin as a category is predicated on a geographical base. We choose to cluster together theories of African and Latin American origin, relying on compatible terminology which incorporates both geographies in different contexts, such as “the 3rd World,” “the Postcolonial World,” or “the Global South.” Many countries from Latin America and Africa have shared a colonial past. During the post-colonial period, this commonality aided in the convergence of perspectives of multiple scholars from those regions. The rationale behind classifying the Turkic-Islamic World as a single category is rooted in the fact that non-Western homegrown theories usually refer to past thinkers who lived before the age of Western domination. Before European hegemony, Turks not only lived in Islamic civilization, but also played a long leadership role over large segments of the Islamic World.

4.1. Design and implementation of the questionnaire

We directed our survey to International Relations academics in Turkey. Due to the specificity of the research subject, we relied on a narrowed definition to identify our research sample. The survey was sent to academics who teach IR Theory and publish, study, or at least conduct doctoral research on this subject. The questionnaire was applied online between May 24th and June 24th, 2021. The respondents were asked a total of 47 questions, grouped under the headings of participant demographics, the importance of IR Theory for the discipline, its status in teaching and literature, the degree of academic and professional success in IR Theory courses, their interaction with other IR courses, and the participants' approach to non-Western IR theories.

We have grouped the data into five classifications according to their relevance to the specific questions. These are as follows: 1) the objectivity and universality of mainstream IR theories, their relationship to the values and interests of the West, and their usability in non-Western contexts; 2) the Western/non-Western Theory divide and the interaction of IR Theory with other IR courses; 3) mainstream theories and, if any, non-Western theories that the participant focuses on while teaching and researching; 4) participants' outlook on the non-Western Theory debate and its relation to critical theories in the Coxian sense; 5) the threefold distinction between the non-Western theories of Asia, Africa/Latin America, and Turkish-Islamic origins. We will discuss the results with cross-analyses, visualizing them with charts.

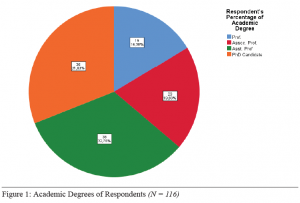

The participant group, consisting of a total of 116 academics from departments of IR at Turkish Universities, represents 57 Turkish Universities and different staff levels, from Professors to PhD Candidates (Figure 1). This number appears to be in line with the overall proportion of such specific sample studies.[32]

The survey questions were designed to examine the extent to which non-Western IR Theories are involved in education and research processes in Turkish academia. It may be argued that the result of the measurement regarding the place of non-Western theories in the teaching process is already evident on the grounds that Western-centered International Relations theories have a stronger weight in the instruction content. However, we believe that a precise understanding on this subject will help us better comprehend the state of non-Western Theory in research. This finding may unearth that the majority of Turkish IR scholars continue to teach what they have been taught and see non-Western literature as too young, low quality, not well-established, possibly marginal, deserving less attention, and outside the scope of standard curricula. But there is no empirical indication that these impressions rely on a serious study of theoretical literature arising from the non-Western world. Moreover, the difference in these standpoints' references to non-Western theory can provide comparable data on the penetration of these theories into IR syllabuses and methodologies. More broadly, our main objective is to answer how International Relations education is practiced in Turkey in the context of the debate on Western and non-Western theory. Thus, we aim to reveal the ways and proportions in which the academic community prefers to use or refer to non-Western IR theories. What are the most known and referenced non-Western approaches in the field of IR Theory? Are some of those approaches more familiar to us than others? We have looked for answers to these questions.

We are aware that the making of studies on IR Theory may be subject to different interpretations. By keeping this in mind, we asked the participants a number of specific questions to see which theories they prefer. Among the inquiries were the level of interaction between IR Theory and other courses, and in which proportion IR Theory contributes to the understanding of other courses in their department's curricula.

Ultimately, our findings gave us the opportunity to examine Turkish academics’ perceptions of the concept “non-Western.” In light of our findings, we can draw leading conclusions about the distinctions made by participants, implicitly or explicitly, between Western criticism and non-Western approaches, and the Western/Asian dichotomy.

5. Evaluation of Turkish IR Scholars' Perspectives on IR Theory

To understand Turkish IR scholars' perceptions and ideas on IR theories, we asked participants to express which IR theory they focus on more while teaching, and which other IR courses they found most connected to IR Theory. The percentages of respondents regarding the theories they focus on more while teaching and researching IR are visualized in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

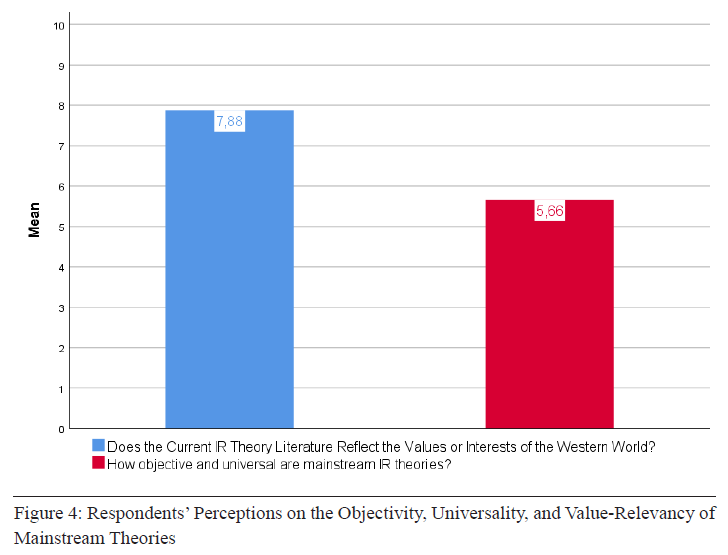

The data visualized in the graphs indicate that Turkish IR scholars are mostly familiar with Realist theories and that they see IR theories mostly in interaction with International Politics courses. These two findings highlight that current topics in the agenda of International Politics can be a factor affecting which IR theory has been given more weight in Turkish academia. Additionally, the weak portrayal of the interactions between Philosophy of Science, Turkish Foreign Policy, or Current Issues and IR Theory helps us understand Turkish academia's relatively indifferent approach to non-Western theories. What can further clarify this point is respondents’ thoughts about meta-theoretical debates on mainstream IR theories. The data presented in Figure 4 is important for this case.

Respondents were asked to rate their opinions on the connection of mainstream IR Theory literature to the values and interests of the West and its level of universality/objectivity on a scale of 1-10. They stated that the current IR literature reflects the interests and values of the West to a considerable extent (average value of 7.88 out of 10), and its level of objectivity/universality is low (average value of 5.66 out of 10).

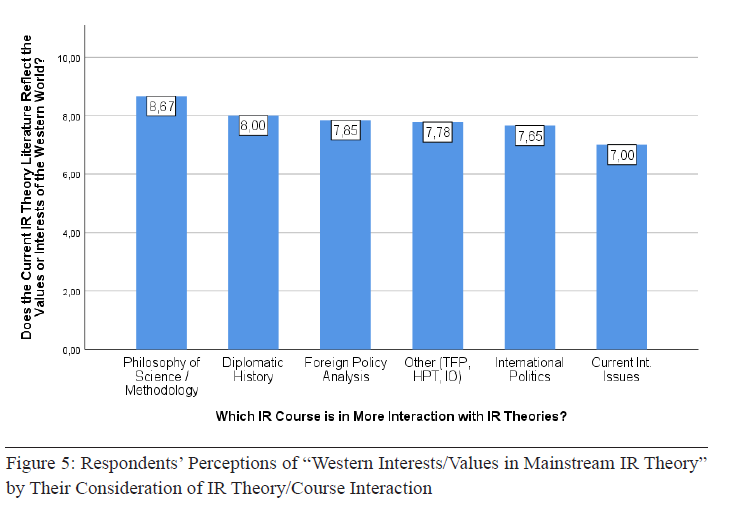

Coxian critical theory underlines the relationship of theory with the interests and perspectives of multiple actors. It is understood that the premise of this thesis, which reflects the political characteristics of the discipline, has also received general acceptance in Turkish academia. Accordingly, there is a meaningful correlation between the belief that mainstream theories are neither objective nor universal and the interest in non-Western theories from Turkish IR academia. Taking a step forward to better focus on the implied relationship, we reached the finding in Figure 5 when we cross-tested the participants' views on the relationship between IR theories/IR courses and their views on the mainstream theory/Western interest/value relationship.

Figure 5 shows the difference between those who associate IR theories with the philosophy of science and those who emphasize their power of explanation in current world politics. Accordingly, those who think that IR theories interact more with courses such as International Politics and Current Issues gave lower scores on the questions about representation of Western interests and values in mainstream IR Theory. Considering that more scholars are in the second group, it can be said that the tendency toward non-Western IR Theory is gaining momentum among those who relate IR theories with Philosophy of Science.

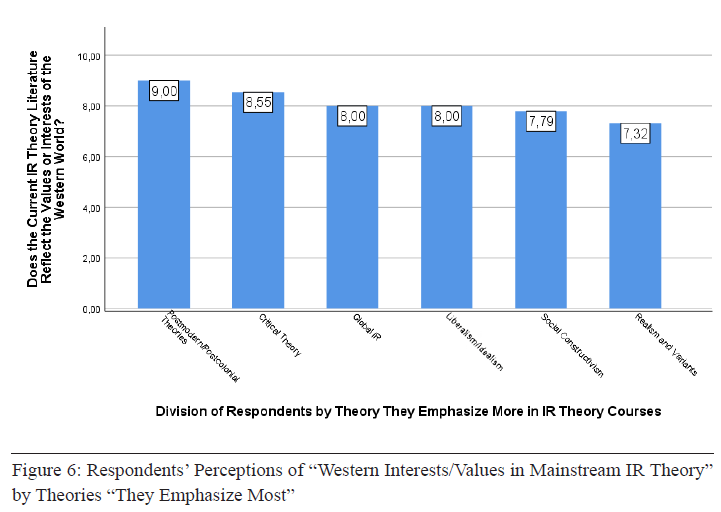

When we established the same cross-correlation according to the theory that the participants focused on in their lectures, another remarkable divergence appeared. This divergence manifests itself in an alignment of postmodern/postcolonial theories and realist theories at both ends. According to the responses displayed in Figure 6, the perception that mainstream theories are related to the values and interests of the West is high in postmodern, postcolonial, and critical theories, while it is lower in Realism, Social Constructivism, and variants of Liberalism. Another point that draws attention here is that the value/interest related nature of mainstream theory has an average value among the participants who state that they follow the Global IR call in teaching. This finding tells us that the followers of Global IR, at least in Turkey, do not associate mainstream IR Theory with Western values/interests to the degree that proponents of critical, postmodern, or postcolonial theories do.

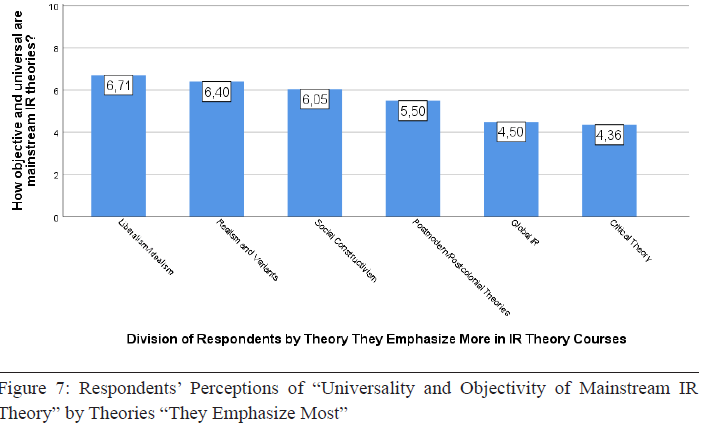

There is also a remarkable margin between the direction of the respondents’ answers about the objectivity and universality of mainstream theories. Figure 7 shows that those who focus on Liberal/Idealist and Realist theories find mainstream IR Theory more universal and objective than those who focus on Critical Theory and Global IR.

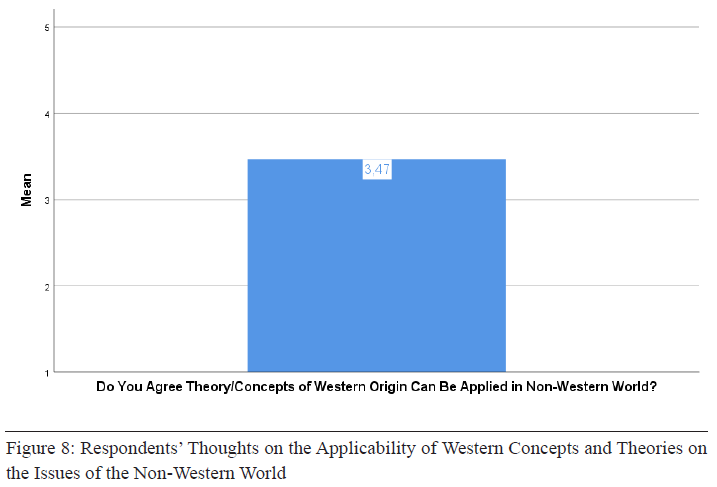

Up to this point, we have depicted Turkish IR scholars’ views of mainstream theories through their perceptions on the courses, interests, values, and objectivity aspects they associate with them. In our attempt to explain the place of non-Western IR theories in Turkish IR scholarship, which is the main purpose of our study, we asked questions from different angles to reveal the respondents’ perceptions on non-Western Theory. First of all, we asked participants to show their thoughts on the usability of Western-based theories and concepts to explain the issues originated in or related to non-Western regions and contexts. In Figure 8, the average score that the participants gave to this question on a 1-5 scale is visualized.

The average of the answers is 3.47 (which corresponds to a level of approximately 70% on a scale of 100). This means that a considerable number of Turkish academics do not see any harm in using Western theories and concepts in issues of the non-Western world. This attitude, which seems to contradict previous results implying that mainstream theories are not objective and value-free, shows that Turkish IR academics' approaches to non-Western IR Theory require further interpretation.

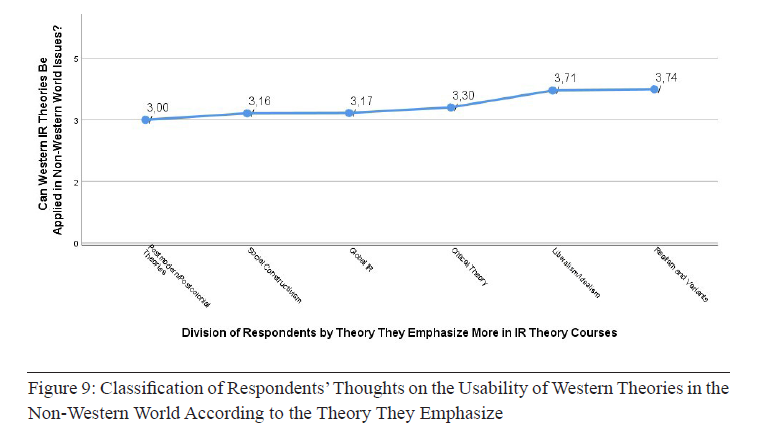

These two data were cross-correlated to reveal the relationship between participants' preferred theories and their thoughts about the validity limits of Western concepts/theories. As a result, we found that those who leaned more toward the core Western theories based on the universalist assumptions of positivist epistemology such as Realism and Liberalism were also in the group that voted the most for the non-Western usability of Western concepts and theories (Figure 9).

In order to shed light on this view in more detail, we asked questions that would unravel the concept of “non-Western” and reveal which non-Western subgroups of theories are more influential to Turkish IR scholars.

6. Turkish IR Scholars' Perception of Non-Western IR Theory

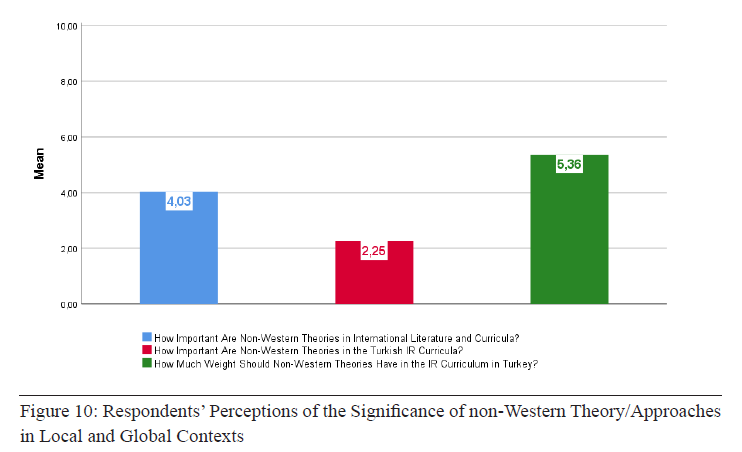

To find out their perceptions of the importance of non-Western theories and approaches in global and local IR literature, respondents were asked to rate their opinions on a scale of 1-10. This question, the results of which we have illustrated in Figure 10, was posed along with the finding that the importance given to non-Western theories in IR Theory courses and research in Turkey is scored approximately 55% lower than the worldwide score. Accordingly, Turkish IR scholars think that the attention given to non-Western theories in teaching and research activities in Turkey is less than that given by the rest of the world, perhaps even the West itself. After this comparison, the question of how important a place non-Western Theory should have in the IR curriculum in Turkey was answered with a score 33% higher than the current global rating. Accordingly, we can deduce that participants desire to see more non-Western Theory references in IR teaching and research in Turkey than they think are currently available in the world.

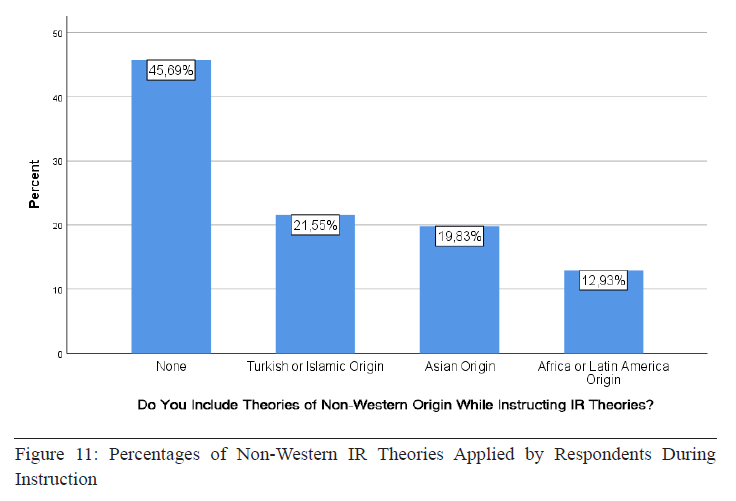

To understand how non-Western theories are practiced and referenced by the Turkish IR community, we posed a question to scholars by classifying non-Western theories into 3 different groups (Figure 11). The tripartite categorization regarding the different non-Western origins of the theories was established on the basis of data obtained by an open-ended inquiry method. We asked separate open-ended questions for each of those in our classification. For example, respondents encountered questions like this: Do you include any Asian-origin theory in your IR Theory teaching?

Respondents freely typed the names of the non-Western theory or theorist they referenced in their instruction or research activities. Those who did not refer to such theories in teaching or research left the open-ended questions blank, and these were coded as "none" in our analysis. When we cross-matched the data obtained from this question, in which we also count the "none" answers apart from these three options, with our other questions, we had the opportunity to make a comparative analysis of Turkish IR scholars according to their use and non-use of non-Western Theory.

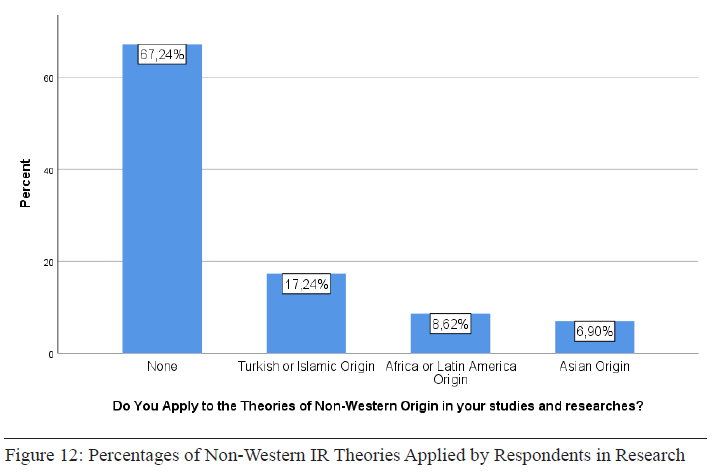

62 respondents, corresponding to 54% of the 116 academicians who answered the question, said that they included at least one of the non-Western IR Theory groups in their lectures. Those who did not include non-Western theories have numerical superiority, and the non-Western Theory group reportedly taught most in Turkish academia is that of Turkish or Islamic origins. When we asked the same question in the form of study/research instead of theory teaching, we reached the results in Figure 12. The ranking does not change, but this time we have a much higher number of “none” answers. Accordingly, we realized that the rate of using non-Western theories in lectures is higher than the rate of using them as theoretical frameworks in research activities. When we recall that Turkish IR academicians are highly suspicious about the objectivity and universality of mainstream theories and see them as highly related to the interests/values of the West, there appears to be a contradiction that deserves more attention. One possible explanation is that while it is easier to include approaches that are not related to the interests and values of the West in a lecture on IR Theory, this opportunity decreases when it comes to study/research due to some reasons like the nature of the established academic order, academic network effect, and lack of knowledge or awareness about alternative theories.

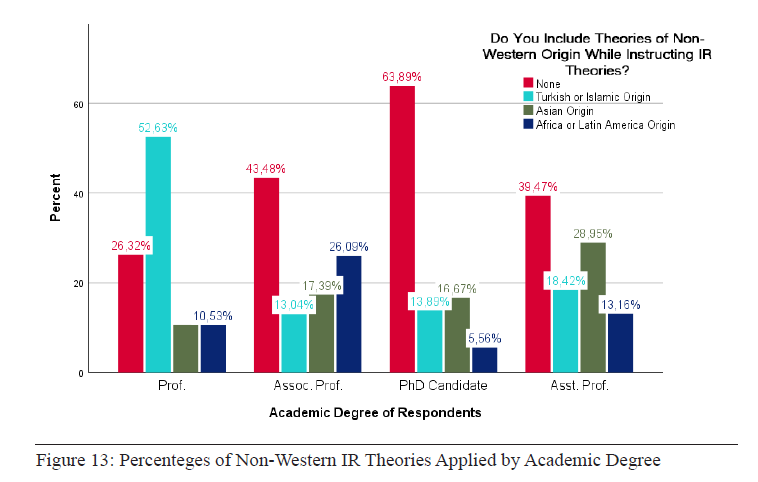

For example, when we distribute the rate of adherence to non-Western theories by academic degree, we encounter the picture that emerges in Figure 13. Accordingly, just the professors marked a non-Western theory group rather than “none” answers.

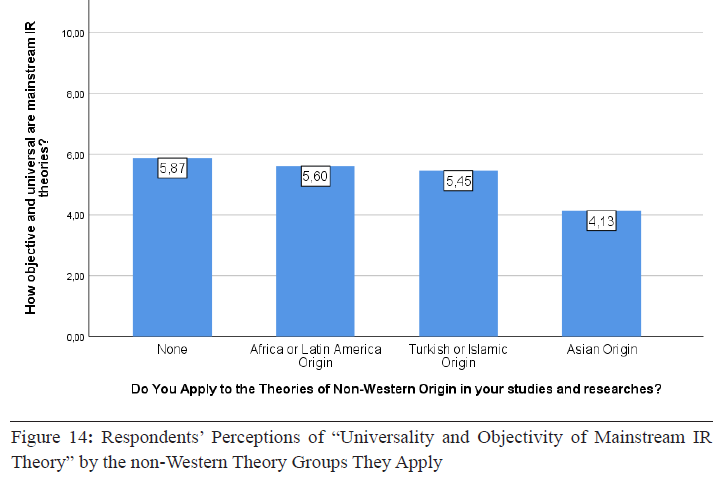

Does the choice of academicians to refer to, or not to refer to, any of the non-Western theories correlate with their perspectives about the objectivity of mainstream IR theories? The results depicted by the answers to this question are illustrated in Figure 14. Accordingly, those who do not use non-Western IR Theory are also the ones who have the most positive opinions about the universality and objectivity of mainstream theories. Users of Asian theories are the most suspicious about these aspects of Western ones.

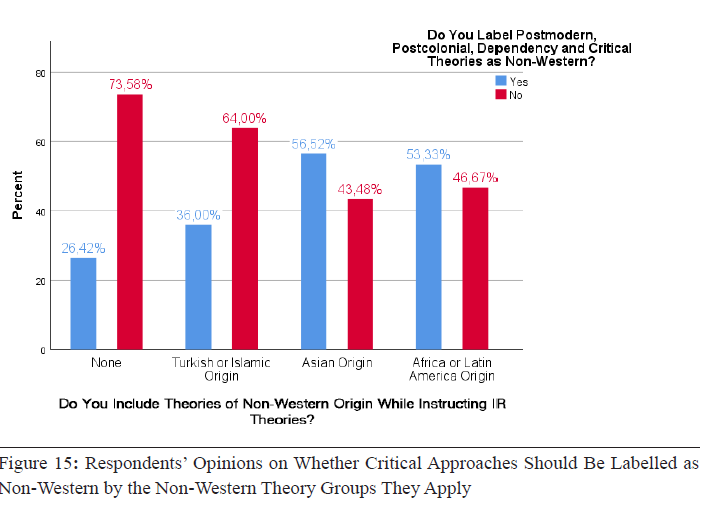

One of the prominent topics in the literature on the debate on non-Western IR theories is whether all schools that criticize the knowledge produced by Western domination can be labeled as non-Western. Although it is accepted that it opens the door to non-Western theories, whether theoretical schools such as Postmodernism, Post-Colonialism, Critical Theory, and Dependency are accepted as non-Western Theory is an important determinant over the respondents’ perceptions of non-Western theories. The distinctive case is that these approaches have rich literature, but mostly they are theoretical schools that have gained a position and are being shaped in the West. We think that whether an academic who claims to use non-Western theories was referring to these schools or not is important. So, in order to get a more accurate picture, we made an additional inquiry (Figure 15).

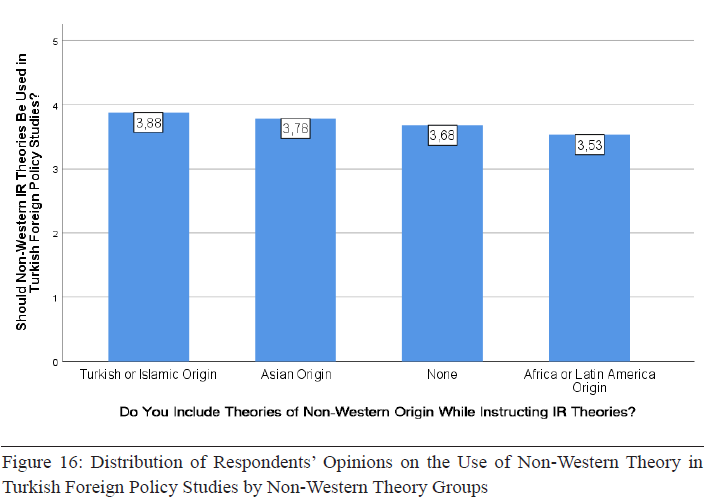

From the analysis of the answers, we understand that those who do not accept theoretical schools with Western-critical content as non-Western are mostly among the scholars not applying non-Western Theory at all. Those who say that they refer to theories originating from the Turkish-Islamic World come second. Accordingly, it turns out that the professors who refer to Turkish-Islamic world-based theories make the distinction between non-Western Theory and Western criticism in the highest proportion among the non-Western IR Theory users. Perhaps for this reason, the highest average of "yes" answers to the question of whether non-Western IR theories should be used in Turkish Foreign Policy studies came from professors familiar with Turkish-Islamic theories (Figure 16).

6.1. Influence rankings of philosophers according to Turkish scholars' references

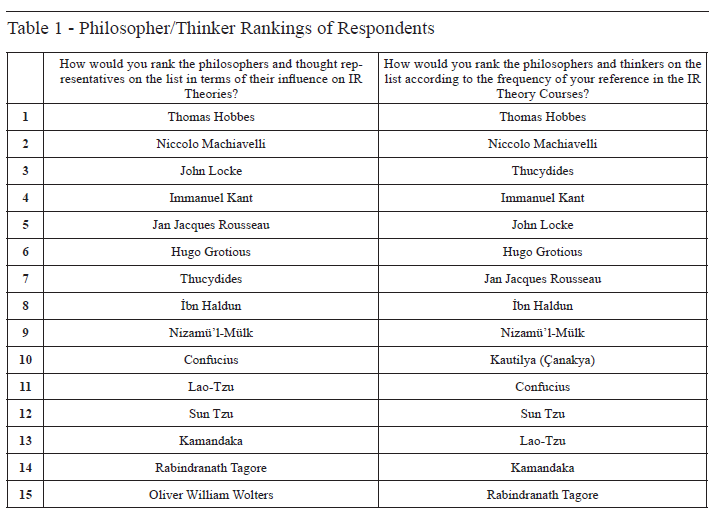

The special question format of the survey makes it easier to measure the impact weight of non-Western philosophers and schools of thought in IR education and research at Turkish Universities. We presented the participants with a list of philosophers/thinkers and asked them to rank these names from 1-15, with the most influential at the beginning and the least influential at the end. The contribution of the philosopher ranking question to the research on Turkish academia is that it can be read alongside the questions based on the non-Western Theory classification in the survey. It is undeniable that Western philosophers had greater influence, but information on whose names came after them, and in what order, offered useful data compatible with our non-Western categorization.

The list consisted of 7 Western and 8 non-Western names. Participants made 2 rankings, one for their influence on IR Theory, and the other for their inclusion in IR Theory curricula.

When we rounded up the most entered names of the respondents, two tables emerged as follows:

When we analyzed the rankings as a whole, the top 5 rows according to their IR Theory influence exhibited some statistical indications: 81.9% of respondents did not name any non-Western thinker; 10.3% of them put a single non-Western philosopher; 2.6% put two non-Western names; and only 1.7% put three non-Western names in the first 5 rows. In terms of their inclusion in IR Theory courses, in the top 5 ranks: 75.9% of respondents did not name any non-Western thinker; 13.8% put one non-Western philosopher; 4.3% put two non-Western names; and again, only 1.7% put three non-Western names in these rows. Looking at the sum of both rankings, the rate of not writing any non-Western names in the first 5 rows became 87.1%.

Although it is not perfect, this table helped to make empirically visible the Western theories' dominant position in Turkish scholarship. The table reveals how well-known non-Western philosophers are among the participant academics. Although it could be assumed that Western philosophers would dominate the top ranks, it should be noted that the vast majority of participants did not use non-Western names at all. When viewed in conjunction with the survey's meta-theoretical questions about the theory's universality and objectivity, these findings may indicate that Turkish academia is uninterested in, if not unwelcoming to, the philosophical representatives of the places that are candidates for developing a non-Western International Relations theory. While Turkish academics view the Western-centered curriculum that molded their academic achievement to be problematic, they appear to have failed to build an alternative teaching agenda to adapt non-Western IR literature. The names listed in the rows just below the first 5 rows in this table could be recognized as the philosophers whose potential to create a non-Western Theory should be studied.

7. Conclusion

This study reveals the traces of the global IR discussion in Turkey by exploring the dynamics of non-Western themes in the Turkish IR community. An overwhelming majority of the participants marked the Realist school as the theory they were most familiar with. Figure 3 shows how the academic community most commonly relates IR Theory with the International Politics course. This might lead us to think that respondents employ theories as a practical guide, and that Turkish academia ascribes an explanatory and problem-solving mission to IR theories.

As a result, it is expected that the Turkish IR community's interest in non-Western theories would grow relative to their skepticism over mainstream theories' problem-solving capacity. That correlation seems to play a bigger role than meta-theoretical considerations. However, it would be vital to conduct further research to assess its consistency. Non-Western IR projects developing a broad and macro theory at the level of International Politics may potentially improve Turkish academics' willingness and interest because concepts and perceptions concerning that level appear to guide the choice of theory.

Turkish IR academics perceive the established theories that they most often apply in their courses and research as representative of the Western world’s values and interests. The questions we asked to examine the meta-theoretical perceptions of the respondents demonstrated how they consider the IR theories inherently biased. The majority of respondents do not consider theories as independent of the interests of the place where they are produced, but they nonetheless continue to employ them. It would be hasty and somewhat misleading to explain this behavior simply on the basis of the IR literature's absence of non-Western theories because theories such as Critical Theory that share the same meta-theoretical questioning do not seem to have constituted the dominant IR identity of Turkey.

We believe that we should consider that the Turkish IR community continues to be interested in mainstream Theory for its explanatory claim to International Politics despite a strong meta-theoretical reserve. As shown in Figure 5, the group that gave impetus to non-Western theories consists of researchers who view IR theories to be more relevant to Philosophy of Science. The above summarizes Turkish academia's stance on mainstream IR theories and the viability of non-Western Theory. When it comes to the participants' perspectives on non-Western theories, the first thing to note is their assessments of the theory's objectivity and universality.

We think that revealing the serious correlation between giving importance to the universality and objectivity qualities of the theory and having an interest in non-Western theories is one of the leading contributions of our research. Through this analysis, we have captured a valuable perspective for further discussion of whether the question of non-universality is an issue of the dichotomic Western-Non-Western context, or if it is inherent to the nature of all theories. With the empowerment of the view that theories cannot be universal,[34] this finding contributes to the relevant literature where we observe a trend that the mainstream is getting localized,[35] that is, abstracted from the claim of universality. In addition, we found strong relationships between the types of theory that are emphasized in instruction and research and the interest/non-interest in non-Western theories. Accordingly, the respondents' approaches to non-Western theories are linked to the theories they mainly refer to either in IR courses or research activities.

If we want to classify the approaches of Turkish scholars to non-Western Theories, it seems appropriate to group them according to their ideas about the objectivity and universality of mainstream international relations theories. 57 participants gave 5 or more points to the related question, and 54 participants gave 5 or fewer points out of 10. The sample is almost exactly split in two here. Therefore, we can argue that one of the most important factors that increased the interest in non-Western IR Theories in Turkish IR academia is the negative judgments regarding the objectivity and universality of mainstream IR theories.

The pioneer approaches that problematize the objectivity, universality, and independence of the value/interest of mainstream theories are critical theories that have gained significant positions in the literature before the non-Western Theory debate expanded. Our reference to "critical theories" is broadly used for theories that are not problem-solvers in the Coxian sense. So, we include different schools like Postmodernism, Critical Social Constructionism, Post-Structuralism, Post-Colonialism, and Historical Sociology in our definition. From the study, we see that as a result of the aforementioned criticism of objectivity and universality, Turkish academia has shifted its direction away from mainstream theories and toward critical ones. We saw in Figure 15 the highest rate of not labeling these theories as non-Western. Based on this, we can intuit that the judgment about the nature of mainstream theories prompts Turkish IR scholars to be interested in critical theories to some extent. Therefore, academics do not feel a need to resort to non-Western theories. The lack of a general non-Western IR Theory may explain the presence of Critical Theory as a substitute. According to the findings, academics seek an alternative to Western theories because they believe they are biased or incompatible with the non-Western world's issues. Academics' lack of sufficient knowledge about non-Western theories can explain this phenomenon, but not the absence of available non-Western theories to meet the demand because the current level of theoretical literature on IR falsifies the latter proposition.

Also, the questions about theory-course connections help develop an impression about the argument that non-Western theories are either lacking or not well-known enough. In contrast with that consideration, the Turkish IR community's silence toward non-Western theories seems more relevant to what non-Western theories are trying to achieve. Maybe we can expect that non-Western Theory initiatives aiming to compete with mainstream Theory will capture Turkish scholars’ attention to a much higher degree. It will be crucial to determine whether there is a link between departing from the mainstream and turning to critical theories at this point because a key component of this inquiry regards the field (mainstream or critical schools) from which the interest in non-Western theories will be transferred. We feel that this may be a focus for further research. We have seen how the representatives of non-Western thought are ranked low in the lists of philosophers. This shows an inconsistency within an academic community that apparently finds mainstream theories biased/subjective. The role played by critical theories may be one of the possible explanations for this paradox.

Acharya, Amitav. “Advancing Global IR: Challenges, Contentions, and Contributions.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 4–15.

———. “Global International Relations (IR) and Regional Worlds: A New Agenda for International Studies.” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 4 (2014): 647–59.

Acharya, Amitav, and Barry Buzan. The Making of Global International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

———. Non-Western International Relations Theory: Perspectives on and Beyond Asia. New York: Routledge, 2009.

———. “Why Is There No Non-Western International Relations Theory? An Introduction.” In Acharya and Buzan, Non-Western International Relations Theory, 1–25.

Andrews, Nathan. “International Relations (IR) Pedagogy, Dialogue and Diversity: Taking the IR Course Syllabus Seriously.” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy & Peace 9, no. 2 (2020): 267–82.

Aydın, Mustafa, and Cihan Di̇zdaroğlu. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler: Trip 2018 Sonuçları Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme.” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 16, no. 64 (2019): 3–28.

Aydınlı, Ersel, and Onur Erpul. “The False Promise of Global IR: Exposing the Paradox of Dependent Development.” International Theory (2021): 1–41. doi: 10.1017/S175297192100018X.

Ayoob, Mohammed. “Inequality and Theorizing in International Relations: The Case for Subaltern Realism.” International Studies Review 4, no. 3 (2002): 27–48.

Bilgin, Pınar. “How Not to Globalise IR: ‘Centre’ and ‘Periphery’ as Constitutive of ‘the International’.” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 18, no. 70 (2021): 13–27.

Bilgin, Pınar, and Zeynep Gülşah Çapan. “Introduction to the Special Issue Regional International Relations and Global Worlds: Globalising International Relations.” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 18, no. 70 (2021): 1–11.

Biltekin, Gonca. “Understanding Turkish Foreign Affairs in the 21st Century: A Homegrown Theorizing Attempt.” Ph.D. dissertation, İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University, 2014.

Blaney, David L, and Tamara A Trownsell. “Recrafting International Relations by Worlding Multiply.” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 18, no. 70 (2021): 45–62.

Cox, Robert W. “Social Forces, States and World Orders: Beyond International Relations Theory.” Millennium 10, no. 2 (1981): 126–55.

–––. Universal Foreigner: The Individual and the World. Singapore: World Scientific, 2013.

Escudé, Carlos. “Peripheral Realism: An Argentine Theory-Building Experience, 1986-1997.” In Concepts, Histories and Theories of International Relations for the 21st Century: Regional and National Approaches, edited by José Flávio and Sombra Saraiva. Brasília: IBRI, 2009.

Friedrichs, Jörg, and Ole Wæver. “Western Europe: Structure and Strategy at the National and Regional Levels.” In Tickner and Wæver, International Relations Scholarship around the World.

Gelardi, Maiken. “Moving Global IR Forward—a Road Map.” International Studies Review 22, no. 4 (2020): 830–52.

Goh, Evelyn. “U.S. Dominance and American Bias in International Relations Scholarship: A View from the Outside.” Journal of Global Security Studies 4, no. 3 (2019): 402–10.

Hagmann, Jonas, and Thomas J. Biersteker. “Beyond the Published Discipline: Toward a Critical Pedagogy of International Studies.” European Journal of International Relations 20, no. 2 (2014): 291–315.

Hendrix, Cullen, Julia Macdonald, Susan Peterson, Ryan Powers, and Michael J. Tierney. “Beyond IR’s Ivory Tower.” Foreign Policy, September 28, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/09/28/beyond-international-relations-ivory-tower-academia-policy-engagement-survey/.

Herbst, Jeffrey. States and Power in Africa. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Hobson, John M. The Eurocentric Conception of World Politics: Western International Theory, 1760-2010. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Hoffmann, Stanley. “An American Social Science: International Relations.” Daedalus 106, no. 3 (1977): 41–60.

Huang, Xiaoming. “The Invisible Hand: Modern Studies of International Relations in Japan, China, and Korea.” Journal of International Relations and Development 10, no. 2 (2007): 168–203.

Hurrell, Andrew. “Beyond Critique: How to Study Global IR?”. International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 149–51.

Inoguchi, Takashi. “Are There Any Theories of International Relations in Japan?” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 7, no. 3 (2007): 369–90.

Krippendorf, Ekkehart. “The Dominance of American Approaches in International Relations.” Millennium 16, no. 2 (1987): 207–14.

Kristensen, Peter M. “Dividing Discipline: Structures of Communication in International Relations.” International Studies Review 14, no. 1 (2012): 32–50.

–––. “Revisiting the “American Social Science”—Mapping the Geography of International Relations.” International Studies Perspectives 16, no. 3 (2015): 246–69.

Kuru, Deniz. “Homegrown Theorizing: Knowledge, Scholars, Theory.” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 7, no. 1 (2018): 69–86.

Lake, David A. “White Man’s IR: An Intellectual Confession.” Perspectives on Politics 14, no. 4 (2016): 1112–22.

Mahajan, Sneh. “International Studies in India: Some Comments.” International Studies 47, no. 1 (2010): 59–72.

Makarychev, Andrey, and Viatcheslav Morozov. “Is “non-Western Theory” Possible? The Idea of Multipolarity and the Trap of Epistemological Relativism in Russian IR.” International Studies Review 15, no. 3 (2013): 328–50.

Maliniak, Daniel, Susan Peterson, Ryan Powers, and Michael J. Tierney. “Is International Relations a Global Discipline? Hegemony, Insularity, and Diversity in the Field.” Security Studies 27, no. 3 (2018): 448–84.

Mearsheimer, John J. “Benign Hegemony.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 147–49.

Milner, Helen, Susan Peterson, Ryan Powers, Michael J. Tiernay, and E. Voeten. “Future of the International Order Survey (Fios).” Princeton University, September 2020. https://scholar.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/hvmilner/files/survey-report-milner.pdf.

Powel, Brieg. “Blinkered Learning, Blinkered Theory: How Histories in Textbooks Parochialize IR.” International Studies Review 22, no. 4 (2020): 957–82.

Qin, Yaqing. “A Relational Theory of World Politics.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 33–47.

Rathbun, Brian. “Politics and Paradigm Preferences: The Implicit Ideology of International Relations Scholars.” International Studies Quarterly 56, no. 3 (2012): 607–22.

Ringmar, Erik. “Alternatives to the State: Or, Why a Non-Western IR Must Be a Revolutionary Science.” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace (2020): 149–62.

Salter, Mark B. “Edward Said and Post-Colonial International Relations.” In International Relations Theory and Philosophy, edited by Cerwyn Moore and Chris Farrands, 129. London: Routledge, 2010.

Shani, Giorgio. “Toward a Post-Western IR: The Umma, Khalsa Panth, and Critical International Relations Theory.” International Studies Review 10, no. 4 (2008): 722–34.

Shilliam, Robbie. International Relations and Non-Western Thought: Imperialism, Colonialism and Investigations of Global Modernity. London: Routledge, 2010.

Smith, Steve. “The Discipline of International Relations: Still an American Social Science?” The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 2, no. 3 (2000): 374-402.

Tickner, Arlene B. “Core, Periphery and (Neo) Imperialist International Relations.” European Journal of International Relations 19, no. 3 (2013): 627–46.

Tickner, Arlene B., and Karen Smith. International Relations from the Global South: Worlds of Difference. London: Routledge, 2020.

Tickner, Arlene B., and Ole Wæver. International Relations Scholarship around the World. London: Routledge, 2009.

Turton, Helen. International Relations and American Dominance: A Diverse Discipline. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Voskressenski, Alexei D. Non-Western Theories of International Relations: Conceptualizing World Regional Studies. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Wæver, Ole. “The Sociology of a Not So International Discipline: American and European Developments in International Relations.” International organization 52, no. 4 (1998): 687–727.

Wemheuer-Vogelaar, Wiebke, Nicholas J. Bell, Mariana Navarrete Morales, and Michael J. Tierney. “The IR of the Beholder: Examining Global IR Using the 2014 Trip Survey.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 16–32.

Xinning, Song. “Building International Relations Theory with Chinese Characteristics.” Journal of Contemporary China 10, no. 26 (2001): 61–74.