Konstantinos Travlos

Özyeğin University

This paper is intended to serve as a show and tell model for graduate students. Sections in parentheses and italics provide a running commentary by the author on the decisions taken throughout the paper. The goal is to permit students to follow the thinking of the researcher and see how it guided the theoretical, methodological and other decisions on content that finally made it into the paper. The paper in question explores how “public” military mobilization can be an attempt by weak actors to trigger intervention by third parties in a dispute with a stronger actor, in the hopes that the third parties will force the stronger actor to accommodate the weaker actor. This attempt is called “compellence via proxy”. In this research I explore why in reaction to failure, some weak actors are able to avoid escalation to war, while others are not. I posit that the flexibility of the decision makers of the weak actors is influenced by their ability to overhaul their winning coalition. A large-n evaluation of 68 cases of “public” mobilization, and an evaluation of six Balkan state mobilizations in the 1878-1909 era, do not support the idea that the size of the winning coalition, a part of the factors determining overhaul, has an association with war onset or its avoidance.

1.Introduction

The following article has a dual role. In it I present a research project focusing on how the interaction of military mobilization and the ability of decision makers to overhaul their winning coalition, impact the onset of war when attempts to trigger “compellence via proxy” fail. At the same time there is a paper within the paper, in which I try to explain and comment on the decisions that led me to pursue this topic, and how to evaluate it. Those sections will be enclosed in parentheses (and will be in italics). The goal is for the interplay of the main text and the (commentary) to provide students with a glimpse into the actual process of paper construction. This paper was built on purpose for the wider education project. Some readers might find it helpful to first read the paper without looking at the (commentary), and then re-read the two texts combined in order to explore their interplay and the construction of the research.

One of the main areas of focus of the rationalist theory of war is on the signaling role of military mobilization concerning intentions during conflict bargaining.[1] In a world of incomplete information and uncertainty about intentions, costly military mobilizations are the most costly signaling tool available to decision makers outside of war itself. Indeed, mobilization can be more financially costly than engagement in some of the less deadly forms of militarized disputes. At the same time mobilization is also a war-preparation measure the goal of which is to give an early military advantage to the first mobilizer. This dual nature of mobilization has led to the consideration of mobilizations under two separate categories; “public” and “private” mobilization.

(One of the most interesting characteristics of mobilization is that it can be more financially costly for a state than even a low intensity war or a militarized dispute. It is also a rare event. Finally, it is hard to clarify between motivations that see mobilization as an attempt to negotiate a better peaceful bargain, and those that see it as war preparation. Rare events that are also characterized by indeterminacy about motives tend to be explored by scholars using rational choice methods. The issue is two-fold. The lack of a big number of event occurrences precludes the use of large-n studies since the non-event observations will overwhelm the event observations. Furthermore, the number of observations might also be too few for resulting in stable large-n models. A discussion of these issues can be found by those interested in King and Zheng.[2]

The other reason is that in events where motives are indeterminate the only way to get a handle on the possible motivations is by making a number of assumptions and following them to their logical consequences. This is the case with events like deterrence or mobilization, where the same observed behavior might be the result of any number of motivations, and the behavior itself cannot provide indicators of motives. For example, the case of an actor making an accommodative move in a crisis might be ascribed to deterrence, but also could simply be the result of the lack of any aggressive motive. The event itself cannot help us understand the motives. But a rational choice framework can lead us to compare the actualized behavior to the expected behavior under certain assumptions. It can also hopefully point to empirical implications that can be explored in case studies.

My first exposure to rare events was during a study of war initiation using politically relevant directed dyads in my PhD studies. These events are dyads where you have a separate observation for Year X State A-State B, and Year X State B-State A. It is the usual modeling technique for when you care about who is doing something to whom (war initiation), rather than what is happening (war onset). The usual number of observations in such evaluations can run in the hundreds of thousands, while the positives, war initiation, will usually be less than a thousand. As a result, getting statistical significant results is extremely hard for the reasons noted by King and Zheng. Instead one must either use modified large-n models or prefer qualitative studies of a smaller number of cases.)

The goal of “private” mobilizations is to maximize the ability of a state to win a war. It thus eschews the declarative character of mobilization as a pre-war bargaining tool. Instead the effect comes during the war, where it can lead to either early capitulation by the target, or extremely long wars due to initiator unwillingness to give terms. “Public” mobilizations on the other hand are mainly aimed at the pre-war bargaining, with the goal of signaling the “strength” of the position of a state on an issue with the hope that this will trigger negotiations. If war happens, “public” mobilization is likely to produce short duration wars, where the initiator is more likely to offer terms. War in the case of “public” mobilization is the result of the power shifts associated with mobilization leading to commitment problems that can lead to war. These commitment problems result from the possibility of re-covering the sunk costs of mobilization, which are given, through the variable military advantages it gives during a war.[3]

(Writers can be divided into two categories. Those who first think and then write and those who write as they think. The first category tends to have a much more pleasant time in writing, than the second. For the second case, to which I belong, the drafting process is much longer. When planning projects, bear in mind the type of writer you are. Part of this is “natural” dispositions and temperaments, and can be ameliorated by training, but I have found that there is a limit to that. A major issue is how much of the information of your paper will you put in the introduction. Put too little and readers will be unhappy. Put too much, and you are repeating information. This partly depends on the audience also. For example, scholars working in the quantitative peace science tradition tend to prefer short introductions, scholars working in more classical paradigms, prefer longer)

Some “public” mobilizers might be willing to risk the war gamble thanks to the hand-tying effect of mobilization. This effect is the sunk costs of mobilization, which can only be recouped by either gains in bargaining, or by the potential military advantage of mobilization in war. But some of the “public” mobilizers are true “pacifists” in that the potential benefits of war are always outpaced by the sunk costs. Let us call them “weak mobilizers” to differentiate them from “strong” states that prepare for war. For “weak mobilizers” mobilization has only a declarative purpose. It is a negotiation tool, and perhaps a desperate one. In many cases “weak mobilizers” might be seeking “compellence via proxy”, in which case their mobilization seeks to trigger action by stronger third parties that then compel the intended target to grant some pacific bargain that will recoup mobilization costs. If this fails to engender a negotiated bargain and the target prepares for, or initiates war, the rational thing is to back down. Some do, but some are not able to do so and find themselves in a disadvantageous war. In this paper I focus on the correlates that can account for the difference between those “weak mobilizers” who are able to avoid war when their gamble fails, and those who are not.

(The rational choice literature in mobilization uses the term “strong” for some of the actors. It has not used the term “weak” in this context. Thus the term is open for use. Keep your eyes out for such situations. Rather than creating a neo-logism, a new word, for a term, you can cut down on the jargon by using useful antonyms for concepts, which have not been utilized fully in the literature.

My first exposure to rational choice works was during my MA studies at the University of Chicago. This was especially in the study of deterrence, where the approach dominates. But I did not fully grasp its rules until graduate studies at the University of Illinois. This project began from a simple question: What other phenomena of international relations are similar to deterrence? Have they been explored by the existing literature? What are the gaps? Mobilization was that similar phenomenon, and I noticed the gap when it came to looking at “weak” mobilizers.)

As part of this exploration I develop an explanatory story of the conditions under which “weak mobilizers” will conduct a public mobilization, and why some are able to back down when this fails to bring about a positive bargaining shift, while others get dragged into war. I argue that a central variable here is the ability of decision makers to overhaul their winning coalition. This is because the hand-tying effect of mobilization strengthens hardliner members of the winning coalition. In rational choice terms it increases the audience costs of accommodation. As a result, accommodation is more costly than military defeat, leading to preference for a disadvantageous war. However, if the decision makers can overhaul the winning coalition, they can then open up domestic space for accommodation, and thus avoid war.[4]

To evaluate this argument I use a multi-method approach. I use a large n-analysis of mobilizations in crises and Militarized Disputes (henceforth MIDs), and before wars to see if the ability to overhaul the winning coalition affects the ability of “weak mobilizers” to avoid going to war. I argue that an empirical differentiation between “weak” and “strong” users of “public” mobilization is the duration of the period between the onset of mobilization and the end of a crisis or initiation of war. The longer this is, the stronger the likelihood that we are dealing with a “weak mobilizer”. However, since mobilization studies are subject to the same limitations concerning intentions as deterrence studies, I also look at the case study of some of the Balkan State mobilizations in the period 1878-1909.

(As noted before, any phenomenon of international relations which is tied to the question of intentions tends to be very hard to observe. This makes large-n study and even comparative case studies quite difficult. Keep this in mind with your own concepts and items of study. If intentions play a big role you may very well have to limit your analysis to the use of rational choice theory in combination with detailed single-case studies. If you are able to do a comparative case study, then this will likely make your research more persuasive. However, combining this with even some simple large-n analysis will also enhance your project.)

I argue that the empirical conditions in the Balkans between the signing of the Treaty of Berlin of 1878, and the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, were conducive for “public” mobilization by “weak mobilizers” as a way to gain Great Power intervention in local crises and make up for their weakness vis-à-vis their targets. Sometimes this worked spectacularly, as was the case of the Greek 1880/1 mobilization over the cession of Thessaly. Sometimes the attempt would fail and lead to a diplomatic retreat but avoidance of war, as was the case with Serbia in 1909. And sometimes it would backfire leading to dis-advantageous wars, as was the case with Greece in 1897.

(Simple case studies can always be a good complement to large-n studies. Multi-method papers are hard to publish as, due to space restrictions, most venues prefer to focus on either qualitative or quantitative. But if well done, these are the papers that are more likely to be published in the top tier journals.

I encountered large-n studies for the first time during my MA studies at the University of Chicago. The introduction was largely shallow, indeed dismissive. It was during the PhD studies at Illinois, that I understood the logic and usefulness of large-n studies. My undergraduate education provided no such exposure, which made my training in large-n studies harder, compared to peers who had been introduced to such methods early on.)

2. Mobilization and Its Role in Bargaining

Mobilization has been at the center of two literatures in international relations. The first is the literature on the influence of military doctrine and the offense-defense balance. The other literature is the rationalist theory of war.[5] It is to this second corpus of work that this study is addressed. This literature is heavily reliant on the use of game theory to derive theoretical findings based on a set of assumptions about actor goals as a way to address the lack of observational data on decision maker motives. I will now briefly summarize that literature.[6]

The rationalist analysis of mobilization was incidental to its role as a strong signaling device due to sunk costs.[7] The development of the concepts of “private” and “public” mobilization only came when analysis moved to the influence of mobilization on war outcomes.[8] “Private” mobilization was seen as war inducing because i) it made mobilizers less willing to avoid military action and ii) because such action is likely to be accompanied by surprise, it undermined deterrence by the target. In another name, “private” mobilization fostered conditions of war-inducing deterrence failure. In reaction there was an assumption that “public” mobilization was pacific. Slantchev questioned this and noted the double character of military mobilization. It is a sunk cost, that makes war less likely by credible signaling, but it is also a hand-tying feature, that makes war more likely by affecting the payoff of any war for both target and initiator.[9]

Tarar studied how power shifts brought about by mobilization within a crisis can lead to war due to commitment problems, even as they decrease the likelihood of war due to private information.[10] The problem is that if mobilization results in a power shift sufficient to exceed the bargaining surplus, this triggers Powell’s general inefficiency condition that leads to war due to commitment problems.[11] To put it simply, if the gain in military capability via mobilization is large enough as to give a first strike advantage to the initial mobilizer, it is likely to lead to fears that even if the target accommodates, it will still be attacked. If the target state expects this to be the case, there are powerful incentives to launch a preemptive war. This is especially the case with gradual mobilization, which is almost always “public” as the time taken up by the process negates any element of surprise. In this case mobilization is done in stages seeking bargaining points. For Tarar this creates a commitment problem as any bargain at one point, may be overturned by further mobilization at another point.

Mackey completes the picture by looking at whether “public” or “private” mobilization actually confers any advantages if war breaks out. By looking at the duration of war he finds indicators that “private” mobilization increases the likelihood of an early submission by the target, but if that does not happen, then the war is likely to last longer. “Public” mobilization is likely to lead to wars of medium duration. The reason for this is that by revealing information about resolve it fosters the adjustment of combatant goals during the fighting to a bargain that ends the fighting. In another name “public” mobilization, unlike “private” mobilization, enhances the information revealing function of conflict[12].

(The literature on mobilization is small. This is another characteristic of the study of topics where intentions are important, and thus observational data hard to generate. It is always better to try to build a story of the development of a research program than to just list references. In general, a good literature review is structured by your argument. Previous literature is explored in relation to the elements of your argument. How does it provide the foundations for your own argument? What gaps of the previous literature you are trying to address? What interactions of previous works have been missed that your work consummates? What previous findings support elements of your argument? Which findings are you trying to advance? How do the works in a research program build up on each other and towards consilience? In other words, you need to show how your own contribution is a logical result of the existing literature and how it advances it.)

One of the problems of the above literature is that it does not sufficiently differentiate among the goal of “public” mobilizations. While in all cases the goal is to reveal information in pursuit of a non-violent bargain, the context might have a big impact on whether the bargaining process will collapse to war. This is because “public” mobilization might have both a negative, deterrent goal, and a positive, compellence goal. Deterrence can come in two forms. The first is mobilization with the goal of deterring a negative action from a target. This is classic deterrence. However, a special sub-case is “armed neutrality”. In this case the mobilization of a state is in reaction to the onset of war in its neighborhood. In this case the goal is to deter war diffusion, rather than war onset.

(This is where I lay forth the weakness of the past literature. In this case we have a classical example where new research strands are uncovered by “un-packing” a previously used concept into its constituent parts. A problem in this case is that I open the concept of “public” mobilization based on intentions, the very thing this field of study has an issue with observing. This means that the most crucial step in this paper is not the explanatory story, but a clear statement of persuasive empirical implications for the two different mobilization motives. This is the only way one can build the space for conducting large-n observational studies of different intentions. The explanatory story on the other hand would be more important in a study whose goal is to add a new concept, and more importantly to develop a new theory, which is essentially to explain the mechanisms by which one concept “causes” another concept. Because here I am more interested in observing a previously un-observable concept, the main explanatory task is to justify the connection between my observable variable, duration of mobilization, with the concept I seek to empirically grasp, motivation for mobilization.)

The other goal of “public” mobilization is compellence. In this case the goal is to engender a positive change of behavior from parties. There are two different types of mobilizations seeking compellence. In one case, the mobilizer seeks to compel the target to grant an issue position. In the other case, the goal is to compel third party actors to act in order to indirectly compel the target. From the perspective of rational choice, the two strategies do not differ. But the different mechanism of compellence in the two cases, direct and by proxy, has important theoretical implications about both the initiation of mobilization, and its failure. In the second case, very weak actors, that would normally not attempt direct compellence towards stronger actors, may attempt to trigger action by stronger third parties, which can then compel the relationally strong actor to accommodate the weak initiator of mobilization. This is “compellence via proxy”.

“Compellence via proxy” is an interesting case. If successful, it permits a weaker actor to compel a stronger actor, via the action of third parties that meet or exceed the strength of the stronger actor. It is also very risky, as the success or failure of the policy relies on the actions of third parties. Empirically the third parties have usually been major powers. The initiators of mobilization in this case have historically being minor powers seeking to compel a stronger minor power or other actor. Mobilization seeking to trigger “compellence via proxy” is the focus of this paper. I will briefly explore the logic that leads states to attempt it, and the conditions under which it is likely to be attempted. My main effort explores what happens when it fails. When the third parties refuse to act in the interest of the mobilizing state, and thus when it is left to face the target of the compellence demand, why are some such actors able to back down and avoid escalation to war, while others are unable?

3. The Logic and Pitfalls of Compellence via Proxy

The explanatory story begins with the assumption that states are made up of two political constituencies relevant to foreign policy decision making. The elites in government, who are the main decision makers, and the winning coalition which is the minimal proportion of the selectorate, those who can participate in the process by which elites in government are chosen, that the elites in government must have the support of, in order to maintain their position. Elites in government engage in international politics in reaction to demands from their winning coalition.[13]

The issues over which the winning coalition will demand action will vary according to the issue cycle.[14] But what does not vary is that the primary goal of the winning coalition is to satisfy its stakes on issues. The primary goal of the elites in government is to remain in power. Both constituencies are instrumentally rational. If the elites in government fail to pursue policies that satisfy the winning coalition, it will defect and thus lead to the collapse of the elites in government. Thus elites in government have an incentive to pursue the interest of the winning coalition up to the point where that pursuit does not endanger their ability to retain power.

(The Issue paradigm of Vasquez and Mansbach, based on viewing world politics through the concept of issues, is one of the most under-utilized tools in the study of international relations. It places domestic politics squarely in the center of the causes of international behavior, without discounting how the international environment affects the life-cycle of issues. The only auxiliary theory to point for the paradigm is Steps to War by Senese and Vasquez, presented in a book published in 2008.[15] However the pre-theory is flexible enough to accommodate theories that were not developed within it. This is the case with Logic of Political Survival. The combination of the two can lead to a richer story of the rise and fall of issues and how these are tied to the interplay of domestic political constituencies and international factors.

The scholar should be open to exploring the potential links between a paradigm and theories developed outside the paradigm. Efforts to explore such links are possible paths to consilience, but must be done in a systemic manner not to lead to ad-hoc connections that undermine rigor.)

Military coercion is one of the most powerful and problematic tools available to elites in government for pursuing their goals. The promise of military coercion is that in comparison to pacific tools, if it is successful it can minimize the size of the accommodation of the defeated that is necessary for resolving the issue in a satisfactory way. The danger is that it is costly and can lead to war. War is dangerous because the costs associated with it can endanger the goals of the elites in government, the winning coalition, or both. A military defeat may lead to government change. The war might harm the stakes of the winning coalition in important issues (for example destroying industry for industrial elites). Military coercion thus is a risky gamble for elites in government. They are more likely to take it when they are either confident that it will not lead to war, or when they are confident they can win any war that erupts.

(Whenever you use the Rationalist Theory of War you have to answer the question of “why would governments engage in the gamble?” The rationalist answer--the trinity of commitment problems, private information, and issue indivisibilities--is a good abstract treatment but not satisfying. States go to war, and it is evident empirically that the march to war is not always just a gamble of the government, but a demand of domestic constituencies. Once we consider the role of constituencies it becomes easier to begin grasping empirical correlates that foster or dampen the rise of the three rationalist paths to war. In other words, it may be worth relaxing the simplicity of rationalist frameworks in order to be able to grasp them empirically. But this should never entail breaking the assumption of instrumental rationality.)

From the above we can argue that it is very unlikely for the elites in the government of a state that is weaker in military capabilities compared to another state to try military coercion against that stronger state. This is because the stronger party will not take the military coercion as a serious threat, and because it can always threaten war to force an end to coercion activity. In the face of these potentialities the weak state has only two options. The first is to enact military coercion when the stronger state has been forced to expend its actualized and latent military capabilities against other threats. This creates a momentary window of parity, or advantage for the weaker state. The second is when the action of the weaker state can trigger action by third party actors who are stronger than the target of the weaker state, and who will then take action to compel the strong target to accommodate some of the demands of the weaker state. This is the essence of “compellence by proxy” and my focus.

(In reality at this point of this exercise the focus is rather abstract. For example in the empirical section you will definitely see cases that do not fit perfectly the “compellence via proxy” concept. At an early stage when you are trying to nail down the empirical relevance of your ideas, some ambiguity is necessary in order to lead to a better final product. Being too precise at such an early stage might result in a variable that is so restricted as to be irrelevant, that is, being so rare as to be idiosyncratic. Because the study of international relations seeks to uncover regular behaviors in international politics, idiosyncratic events are not of interest. They are the proper venue of the study of history, or of current events. At the same time, precision must never be taken to the point where the resulting variables are essentially unique. A model that is too exact a replication of reality is reality, and thus not useful as a guide to reality. One can say that in the social sciences precision must be in the service of abstraction.)

What kinds of states are more likely to react positively to such attempts to elicit “compellence via proxy”? These are probably regional or major powers. This is because these are the states more likely to have the willingness and opportunity to react to “compellence by proxy” attempts in a positive manner. They are strong enough to be able to coerce the stronger party in a dispute. If they also value stability in the region or are opposed to letting the weaker party pay the price for a failed “compellence by proxy” attempt, then they are able and willing to intervene. However, their capability advantage also makes them able to manage the consequences of a failure of the policy of the weak state. They could ignore the bait, let the weak state enter a dis-advantageous war due to failure of “compellence via proxy”, and then intervene after the war to determine the contours of the peace agreement. They can even let the weak state pay the full military price of its gamble. This is the central pitfall of a policy of “compellence via proxy” for the weak states. If the stronger third parties do not take the bait, then they are dangerously exposed to their target.

(You will notice that here I do not define weak or strong. This is on purpose. At this point I am still wrestling with the concept. It would be easy to define weakness in terms of military capabilities, but a state might also be “weak” because non-material conditions greatly limit its ability to use power. The framework of opportunity and willingness for the engagement in military activity, developed by Siverson and Starr in 1990, indicates that “weakness” might reside in either element of the decision.[16]This is important, as material weakness is observable and measurable, but motivational weakness on average is not. This means that the concept of weakness one uses can have a crucial determination on the kind of variables that can be extracted, and in turn the kind of papers one can write on them. This is always the case with any concept that has both a material and ideational element. More precision is required, but for the time being I am focusing on the cases of mobilizations that led or did not lead to war, as opposed to the specific characteristics of the actors. Indeed it may be the case that this paper is doing too much, both looking at the failure of bargaining by mobilization, and trying to build a story of why such mobilization is more likely to fail.)

This risk is especially acute when the weaker party is trying to use “compellence by proxy” to trigger intervention against its opponent by a major power that has important relations with both disputants. Because such a major power would lose in the political arena if its two allies fought, it would have incentives to intervene and avoid such a war result. Nevertheless, being forced to choose among its allies or clients in a dispute could also hurt it, by leading one of the two to potentially defect. The competing incentives can lead to unwillingness to intervene until it is too late and war has erupted. The major power may also hope that by staying aloof it will force the weaker ally/client to back down without the need to lose political capital by intervening. It might also wish to “teach” the weaker power a lesson by permitting it to be defeated and then intervening to modify the result of combat in order to strengthen its position with both clients.

Intervening or not intervening is a risky policy for the major power. During the crisis that led to the 2nd Balkan War, the Russian decision makers fully understood why their state would be a target of an attempt by Bulgaria and Serbia to trigger “compellence via proxy” against each other. Fearing that if they intervened, they would lose one of the two allies, Russia stood aloof. The result was war and the defeat of Bulgaria. The Russians did intervene after the war to seek to shore up their weakened position vis-à-vis their defeated client, but ultimately failed to do so, losing Bulgaria to the Central Powers.

The above discussion indicates that gambling on “compellence via proxy” is a very risky gamble for a weak state, even when the potential intervener has both the opportunity and willingness to intervene. Considering this, when such a policy fails, why are some of the decision makers able to back down and avoid the escalation to war, while others fail? This then is the central question. We can conceptualize “compellence via proxy” as the specific instance of a more general phenomenon of bargaining by mobilization.

(Our question is partly theoretical--who will and why will they engage in “compellence via proxy”, and partly empirical--why it fails. A better project would have three papers-one focusing on the conditions that lead states to attempt “compellence via proxy”, one focusing on why it fails or not, and one on why do some states avoid the cost of failure (war), while others do not. When you broach a new topic it is quite natural that a lot of ideas will co-habit the early manuscripts. That is fine as long as you use it as a tool to lay out the future project, and as long as you have the resources (in time, interest, and co-authors) to pursue the different strands. Trying to answer all of them in one paper is a recipe for failure. But at this point putting them down and seeing how they interplay is worthwhile.)

A policy of “compellence via proxy” requires increasing the probability of war so as to alert potential interveners to the need to consider action to avoid war. The most powerful non-war signal that can be sent is the “public” declaration of partial or full mobilization. The heavy economic and social cost of mobilization is a powerful signal of intentions. Furthermore it is likely to trigger military action by the target state. The elites in government that begin this process are likely aware that they will probably lose a war if it happens. But they bet that there will probably be intervention that will avert the war and permit them to satisfy some of the stakes of their winning coalition in the dispute. However, mobilization has another domestic consequence. Its hand-tying feature greatly increases the political cost of backing down. There are many reasons for this.

First, the economic loss suffered by the society and potentially members of the winning coalition will increase the stake of the winning coalition in a resolution of the dispute that helps recoup their losses due to mobilization. Τhus the winning coalition is unlikely to permit accommodations that do not recoup its losses. More importantly the preparation for war associated with mobilization will strengthen the political position of domestic hardliners committed to escalating the crisis to war.[17] As a result, avoiding war after a failed “compellence by proxy” attempt can be as costly as losing the war for elites in government. Either option can lead to their fall from government.

Caught in this bind most governments would probably choose escalation and war. This is because the threat of overthrow due to action by the winning coalition is always greater than the threat from war, simply because war is the realm of chance.[18] The weak state has a non-zero probability of winning the war. Intervention might follow the onset of war and shore up defeated elites in government. Thus as long as the chance of being overthrow by a winning coalition that is dissatisfied due to accommodation after a failed attempt at “compellence via proxy,” is higher than the chance of overthrow due to war, war will be the rational choice. But if that is not the case, if somehow the chance of overthrow by an angry winning coalition can be reduced below that of war, then diplomatic retreat will be the rational choice.

(War has its own logic. More importantly war will create its own constituency that will drive for war. This is something that many of us forget. We assume a linear relationship between government decision and outcome. However, the reality is that war is a dynamic phenomenon and even just the preparation for it can have massive consequences on domestic politics that make it harder for governments to change course. This is something Vasquez and Senese point out in Steps to War, but are not able to empirically evaluate since that would require data on the balance of hardliners and accommodationists in government and how that balance changes due to decisions made by governments. Large-n Data collection for such a project would be a monumental task, but could greatly enhance our study of war and peace.)

The main determinant of the risk posed by a dissatisfied winning coalition to the elites in government is the ability of the elites in government to overhaul their winning coalition.[19] Overhauling the winning coalition is the process by which elites in government can change the composition and size of their winning coalition in order to manage dissatisfaction. It can be done by non-violent means, like Gorbachev’s overhaul of the Soviet winning coalition in preparation of Perestroika. But it can also be violent, like the Stalinist purges. The important thing here is that elites in government that can overhaul their winning coalitions can reduce the risks associated with accommodation policies after a failed “compellence by proxy” attempt. And this threat could potentially be brought below the threat level posed by a dis-advantageous war. When this is the case, in the face of a failed “compellence via proxy” policy, elites in government are more likely to seek to avoid war.

Overhauling the winning coalition is a factor conditioned primarily by the size of the winning coalition. Very small winning coalitions or very big ones are more easily overhauled. Small coalitions can be overhauled quickly, narrowing any window of opportunity for resistance. And, smaller coalitions are likely dependent on the elites in government for their social status, making rebellion risky. Large winning coalitions, like those of democratic states, suffer from high coordination costs, making it hard for a unified opposition to form. Furthermore the large size of the coalition makes it easier for the elites in government to make targeted overhauls without endangering their overall social support. “Logrolled Coalitions” are the hardest to overhaul.[20] Such systems are medium in size – small enough to facilitate resistance coordination, but too big to be easily overhauled. In this case attempts to overhaul the coalition might trigger a political crisis and lead to violent resistance. The coalition is big enough that the resistance can be dangerous to the elites in government, but too small to permit the isolation of recalcitrant members. Thus the ability of the elites in government to overhaul their winning coalitions, primarily determined by size, is the main independent variable that determines whether states in the face of failed “compellence via proxy” politics will be able to back down and avoid war or not.

(Here I would like to make a didactic point. We scholars sometimes forget that governments have some ability to choose who they “govern”. This ability greatly increases the freedom of choice of a government in international politics. We tend to assume domestic politics as either an inhibiting or fostering condition on international outcomes, but one largely free from the manipulation of decision makers. But that is not the case. Decision makers vary in how tied their hands are by domestic groups. Any research design that posits an important role for domestic politics on the international outcomes of the decisions of decision makers, without controlling for their ability to manage their dependence on those domestic factors, is by default making certain assumptions that might not be wise empirically. Ergo, why in this paper the ability of decision makers to overhaul the winning coalition is the most important domestic factor, as it largely determines how restricted or not domestic factors are on decision makers.

My first introduction to this idea was via Bear Braumoeller’s 2012 book “The Great Powers and the International System. This was after my graduate studies.)

From the above discussion I extract the following hypothesis:

H1: A curvilinear relation exists between the size of a winning coalition of a state and whether its “public” military mobilization will experience war onset. Very large and very small winning coalitions will have a negative impact on the probability of onset. Mid-sized coalitions will have a positive impact.

(Curvilinear associations are common in international relations, but also very difficult to deal with in empirical models. Here I decided to go for a basic cross-tabulation as a first “stab” at the data. There are methods for working with them, but sometimes the data one has is not adequate to get the most out of them. This is not the case with cross-tabulations. The primary reason why curvilinear associations are problematic is because most linear models assume a linear relationship between the dependent and independent variables. Cross-tabulations, as well as graphical displays are free from such necessary parametric assumptions. There are large-n regression tools that can accommodate curvilinear associations, like Spearman Rank Correlation and polynomial regression, but there are beyond the scope of this paper. An added issue is that the low number of observations generated by mobilization in interaction with the curvilinear association, make most regression models a risk due to instability that comes from insufficient observations. Remember, in general you should have at least 100 observations, preferably more, before running a regression.

For a general review of statistical techniques of the social sciences, and the advantages of cross-tabulations, a useful guide is Joseph F. Healey, Statistics: A Tool for Social Research. (Cengage Learning, 2014). Cross-tabulations were among the first statistic tools I was introduced to in my MA studies. But it took the PhD, and my work after to fully grasp their importance.)

4. Research Design

I will evaluate the empirical persuasiveness of Hypothesis 1 by two methods. One is a basic large-n study using mobilization data compiled from secondary sources. The other is a series of comparative case studies of mobilizations by Greece and Serbia in the 1878-1909 period. For the large-n study I will cross-tabulate the size of the winning coalitions of the states of interest with the outcome of their attempts to trigger “compellence via proxy” by partial or full mobilization. The data for winning coalition size comes from the Bueno De Mesquita Winning Coalition Dataset 1816-1999.[21] I evaluate the likelihood that any relationship was due to random chance by using the chi-square test of statistical significance.[22] This should not be seen as a full statistical exploration of the data, but instead as a first “stab” at it.

5. Compiling Mobilization Data

One of the challenges of research on the influence of mobilization on interstate politics is the lack of data on mobilizations. The only dataset with some basic information on mobilization occurrence is the Interstate Crisis Behavior (ICB) dataset. The MID dataset of the Correlates of War (COW) project also notes mobilization as a hostility action. Neither dataset provides information on whether the mobilization was partial or full, whether it was “public” or “private”, its duration, and whether it was part of the initiation of the use of force. There is no data on whether a war or MID level use of force was preceded by mobilization.

Additionally, there is ambiguity about what actions count as mobilization. For mobilization to play the role it does in the rationalist theory of war, it has to be costly. But military preparations can take many forms. They can start from putting on alert specific forces, putting on alert the whole army, up to inducting large numbers of the civilian population and infrastructure into the military. Increases in military preparedness simply do not have the economic and social cost of the induction of large numbers of civilians into the military. The last activity is extremely resented by the civilian population, while putting troops on alert is still an intra-military activity that will probably not substantially affect civilians. Consequently the sunk costs and the hand-tying effect of partial or full mobilization, defined as the induction of civilians and the civilian infrastructure into military control, are very different and much more severe than those of putting troops on alert.

(When you are compiling data, always prefer to write down more rather than less information. Always! Even if that information might not be immediately useful for your research, it will be useful for future researchers. Also, always build a small narrative for your cases. However time consuming it is, even jotting down four-five lines, this can be an extremely important piece of information for researchers.)

This is something decision makers understand well as the following example of a letter written by Greek Prime Minister Elefterios Venizelos in 1934 testifies “…He knew (speaking of King Constantine I of Greece) how detested in all conditions is a general mobilization, which detaches from families and work citizens, and which thus and with the associated regulations and rules, deeply shakes and obstructs the normal economic and social life of a country”.[23] Only full or partial mobilization incurs the sunk costs and hand tying effects that the rationalist theory of war has considered important. Consequently, I only focus on such mobilizations for this paper. Another characteristic of this type of mobilization is that it is very hard to conduct it as “private”. The disruption of civilian life will be a big indicator that something is going on, though a potential target may still not be sure about the objective.

The lack of detailed mobilization data forced the two prior projects that used large-n evaluations to evaluate the influence of mobilization in crises, to base their variables on readings of the sources used for coding the initial crisis events.[24] Since the MID dataset does not have narratives and specific sources per case, both Lai and Mackey relied on the ICB case narratives for their variables. For this paper I relied on ICB case narratives to compile mobilizations in crises, either as trigger conditions or as reactions.[25] I used the MID dataset to locate mobilization cases that did not lead to war (via the highest hostile act variable), and then used the COW war data, and the Sarkees and Wayman narratives, and secondary literature to locate cases of mobilization that took place in the lead up to wars.[26]

(The goal of a good large-n dataset is that the researcher does not need to do any extra research. The dataset is complete and reliable enough that it in itself is an authority. If that is not the case, and one must make subjective judgements based on secondary sources, then some of the benefits of large-n study are negated. For example, the fact that the information on mobilization inherent in the available date is ambiguous leads to the necessity of subjective calls about events and their conceptualization. This undermines the authoritative stature of the data-set as a source. Thus researchers using existing datasets to extract mobilization data will have to justify decisions of how variables were created, as opposed to simply justifying the use of the data-set. This is unavoidable during the development of a research project.)

In general, mobilization is rare in international relations. It requires a certain level of bureaucratic and infrastructure development that most states in the history of the modern interstate system (1816 - present) have lacked. It is also a very costly measure that many states simply cannot afford. Finally, in many cases of war, states have chosen not to mobilize. A limited war might be less costly than a war of full mobilization. Thus many states might even eschew mobilization in the case of war. To compile a list, and due to the lack of adequate resources for a full dataset, I took all the cases of mobilization that did not lead to war in Crises and MIDs, and added a random sample of 133 war cases from COW in order to get cases where mobilizations led to war or happened due to war. There are 73 cases of mobilizations that did not lead to war, nine cases of Crisis mobilizations that led to war, 49 war cases in which mobilization happened after the war onset or on onset (and thus of no interest to this paper), and 41 cases where mobilization happened between 1 and 365 days or more before war onset.

(Combining my selected sample with a random sample dampens some of the selection bias inherent if choosing cases. I had to do that due to the lack of resources for a full exploration of every case of Crisis or MID.)

Of the 64 cases of mobilization that did not lead to war, 10 were mobilizations in reaction to ongoing wars. In this case a state mobilizes its armies in reaction to the onset of a war between two other states. These cases are characterized by motivation ambiguity. Mobilization might be an attempt to gain a bargaining advantage against the war opponents. The Greek mobilization of 1878 in the midst of the Russo-Ottoman War of 1877-1878 is an example of this. But it can also be part of a policy of “armed neutrality”. The Dutch mobilization at the onset of World War II is an example of this. But discerning which of the two motives underpin the behavior is not an easy task. While both are a form of bargaining, here we are interested in bargains that seek positive goals, not negative goals like deterrence. At this point it is safer to exclude such mobilizations from our analysis, though the cases are not so many that a future project cannot focus on them. Thus we have 54 cases where mobilization did not lead to war and could be considered as part of a bargaining strategy.

For the 41 cases where mobilization happened before war onset, the range in duration of days is very large (to be exact at least 364 days). The issue is finding a persuasive point after which we can argue that the mobilization was part of a bargaining strategy instead of a war-preparation measure. This can be tricky, because it is a matter of “diplomatic” time. This is the minimum “time” required for a state to a) become aware of the mobilization signal, and b) decide how to react. Changes in technology have greatly affected “diplomatic” time. A process that would require days if not weeks in the early 19th century might be resolvable in hours in the late 20th century. Thus “diplomatic” time is a bit contingent on the technological era. One way to get benchmarks is to compare the duration of the period between mobilization and war for each case, to an average of such durations for similar wars, and then group cases according to the available technology. This is doable.

Fourteen cases were in the 1930-1950 period, when telephone and radio communications predominated. Two cases were in the 1960s-1970s period when more advanced communications methods were available. Fifteen cases were in the 1900-1930 period when wired telegraph and early wireless technology predominated. Two cases were in the 1890s period when the wired telegraph and optic telegraph were the main tools. Finally, seven cases were in the 1816-1880 period, when written and optic telegraph communications predominated.

In the 1930-1950 period the average duration between mobilization and war was 116 days. Eight cases are significantly under this average, and thus can be argued to likely be cases of war-preparation rather than bargaining. The other six cases are sufficiently long to open the possibility that they were primarily bargaining moves that went wrong. Of those six though, four can be safely considered as part of “armed neutrality” policies (Norway, Greece, Netherland and Belgium in World War II). That only leaves the case of the US mobilization before its participation in World War II, and the Italian mobilization before its invasion of Ethiopia (both of which started at least a year before onset).

(Quite obviously the US and Italy cases do not fit well the “compellence via proxy” concept. The Italian case might work more because one could see Italy’s long mobilization as an attempt to force the League of Nations powers to apply pressure to Ethiopia for accommodation. In this case Italian “weakness” would come from issues having to do with domestic politics, or the fear of League reaction. The US case is harder to justify. I include it only because of the paucity of data. Keep in mind that it is better to have some cases that are bad fits than to have to make too many unique exclusions in your research design. The reason again is to avoid such a restrictive set of inclusion criteria that you end up with a list of idiosyncratic cases, from which no useful social-scientific findings can be extracted.)

During the 1960s-1970s cases, Syria and Egypt mobilized at least seven days before the onset of the Yom Kippur war, and El Salvador mobilized 20 days before the onset of the Football War. We can safely exclude the Yom Kippur case, since it has been explored by other scholars and is the archetypical example of “private” mobilization (i.e one that by default seeks military advantage in war, rather than bargaining advantages). The El Salvador case has a sufficient duration of mobilization to onset that it could be treated as a case of “public” mobilization.

In the 1900-1930 period the average duration of mobilization to onset was 15 days. Seven of 15 cases fall well below the threshold and can be argued to be war preparation cases. The other eight cases are long enough to have provided time for bargaining. In the 1890s the two mobilization cases both saw rather long mobilization to war periods. In the First Sino-Japanese War, Japan mobilized 25 days before war onset. In the Greek-Ottoman War of 1897 both sides mobilized at 58 and 56 days before onset. In both cases there is sufficient time for bargaining, and thus both can be argued to be possible cases of mobilization with a bargaining objective.

In the 1816-1880s period the average duration of mobilization to onset period was 82 days. This is heavily skewed by the mobilization of the Mexican army at least one year before the onset of the Mexican-United States of America war. All the other cases are from the Wars of German and Italian Unification in the 1859-1866 period. If we only look at those cases, the average is 33. With that second average there are two cases where the duration is long enough as to permit time for us to argue these were bargaining moves. The first is the Piedmontese mobilization of 1859. This is an interesting case. The Piedmontese government sought to bait Austria to declare war so as to justify a French intervention in the war on its side. This fits the “compellence via proxy” concept, but is an extreme form in which the gambler knows the game is rigged in their favor. Still it was risky in the sense that the French government could always have defected. The other case is the Austrian mobilization, 49 days before the onset of the 1866 Austro-Prussian War. This is also a possible case of bargaining by mobilization. The Prussian mobilization was also 39 days before the war, but we know that the government was committed to fighting. Thus of the seven cases of this period, only three can be considered as possible cases of mobilization for bargaining.

Our data thus is made up of 54 cases where mobilization could have been done for bargaining purposes and did not lead to war and 16 cases where mobilization could have been done for bargaining purposes and led to war. Since two cases were duplicates in the ICB and MID datasets, the duplicates were excluded, leading to a total of 68 cases. If the mobilization led to war, I code the variable as a 1. If it did not, I code it as zero. Thus we have 16 cases of 1 and 54 cases of 0. This is the dependent variable of the analysis.

6. Large-N Analysis

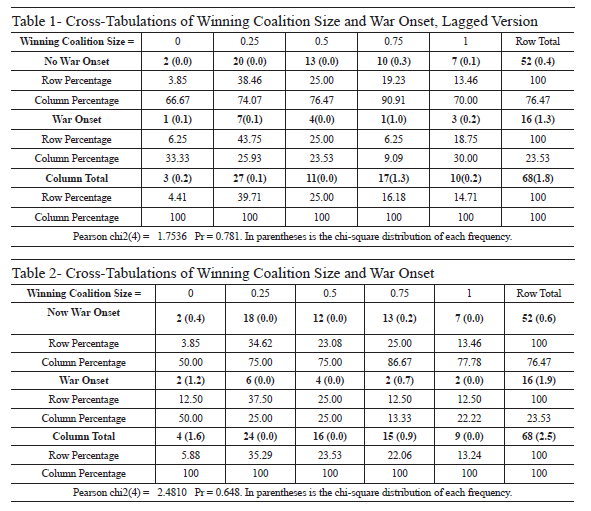

The findings of the large-n analysis are presented in Table 1 and Table 2. In Table 1, I use as the independent variable the size of the winning coalition in the year before the end year of the crisis, or last year of the MID, or the year of war-onset, i.e a lagged variable. In Table 2, I use as the independent variable the size of the winning coalition during the end year of the crisis, or last year of the MID, or the year of war-onset. In both cases the variables do not indicate a statistically significant association. On the other hand I do find elements of a curvilinear relationship between the size of the winning coalition and mobilization being accompanied by war. This is more evident in Table 2 than in Table 1. The Bueno De Mesquita et al variable ranges from 0 to 1, indicating how much of the population is part of the selectorate (there are five levels: 0/0.25/0.5/0.75/1). When you look at the row totals under the frequencies when the war variable is 1, one can see the following.

(Brian Gaines, who taught us statistics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, always lauded the humble cross-tabulation as a statistical tool. They are the most forgiving of the methods available-in the sense that fewer of their perquisite assumptions are violated by the reality of social phenomena. They are simple to use, and they are accompanied by a good set of statistical significance tests. It is a wise move to always begin the evaluation of large-n data with a series of cross-tabulation tests, as they tend to catch some basic problems)

In Table 1, the highest percentages of war onset are in the middle ranges of Winning Coalition size (0.25 and 0.5), which are more likely to be associated with “logrolling coalitions” and thus harder to overhaul. The percentage of war onset increases again at the full democracy tail (Winning Coalition value of 1), though not to a level higher than that present in the mid-range Winning Coalition sizes. In Table 2 this curvilinear relationship is clearer. Again, winning coalitions that fall within mid-range sizes have the largest share of war onsets.

The main culprit for the lack of statistical significance is the fact that in both Table 1 and Table 2, the row percentages for frequencies of mobilizations that did not lead to war are very similar to those that led to war. It should be noted that it is the case that in the mid-range sized Winning Coalition cases the no-war percentages are slightly lesser than the war percentages, and thus we have a frequency distribution that is in agreement with the explanatory story. However, the difference is slight and probably why it did not reach statistical significance. Future research, using more sensitive statistical models might be able to clarify whether we are missing something from the cross-tabulation evaluation. But at this point H1 has been falsified by the data.

7. The Balkan Mobilizations 1878-1909

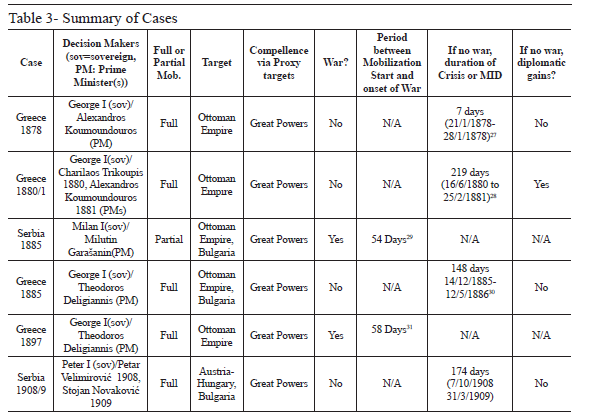

To supplement the large-n study I explore a number of case studies. The cases focus on the Serbian and Greek mobilizations of 1885 in reaction to the Eastern Rumelia Crisis; the Serbian mobilization of 1908/9 in reaction to the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina by the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the declaration of independence by the Principality (Tsardom) of Bulgaria; the Greek mobilization and invasion of Domokos on 21st January 1878 in reaction to the imminent end of the Russo-Ottoman War of 1877-1878; the Greek mobilization of 1880/1 in reaction to the refusal of the Ottoman Empire to cede the Thessalian territories awarded to Greece with the Treaty of Berlin; and the Greek mobilization of 1897 in reaction to the Cretan Revolt of 1896-1897.

(The qualitative analysis I will do here is not a deep case study. Instead I will use the cases to a) see if they corroborate the findings of the large-n analysis; b) provide examples of how the dynamics of the explanatory story play out or not in concrete cases; and c) look for elements missed by the large-n study. A deep case study, would preferably compare two of the cases on a critical test, and use process tracing and primary sources to tell us a story. However the cases I focus on are not well supported by documentary evidence, especially in English, precluding thus a deep case study. A introduction to case studies is John Gerring,“What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review, 98, no. 2 (2004): 341–54).

The six mobilizations had very different results. The Serbian 1885 mobilization and Greek 1897 mobilization led to defeat in disadvantageous wars. The Greek mobilization of 1878 fizzled without leading to war, as Greece failed to trigger “compellence via proxy”, and was forced to back down by the Great Powers before war erupted with the Ottoman Empire. The long term result was diplomatic gains in the Treaty of Berlin, but in the immediate aftermath Greek interests were absent from the Treaty of San Stefano (Ayastefano). This was also the case of the Greek mobilization of 1885, which triggered a naval blockade of Greece by the Great Powers. The Serbian mobilization of 1908/9 also fizzled but Serbia was also able to avoid war with Austria-Hungary or Bulgaria. It did not attain any immediate diplomatic gains. The Greek mobilization of 1880/1 was highly successful as war was avoided and the Great Powers forced the Ottoman Empire to proceed with the cessation of Thessaly to Greece. This is a good example of “compellence via proxy”. Table 3 summarizes the information on each case.

(As much as possible try to summarize qualitative information in visual ways. This includes tables and graphs.)

Can we consider these cases as attempts at “compellence via proxy”? The requirement for this is that the mobilizers have to be “weak” compared to their intended targets, and that there must be strong actors available that have both the opportunity and willingness to react to the crisis and try to impose a pacific solution that might accommodate the mobilizers. The second element is satisfied in the period by the presence of multiple European Great Powers that had expressed an interest in the resolution of issues in the Balkans and had past records of intervention. Indeed, Serbia and Greece had been past beneficiaries and targets of such interventions. Serbia had a great power patron in Austria-Hungary in the 1885 period, and Russia in the 1908/9 period. Greece was a ward of the Great Powers, with Russia, France and the UK having outsized political power, and with recent cases of the two naval powers imposing their will on Greece (1854, 1866), but also accommodating its interests (1868,1881). Thus both states were not irrational in expecting that “compellence by proxy” could work. At the very least their targets, especially the Ottoman Empire, were states of great interest to the major powers, who had fought against them (Russia against the Ottoman Empire), for them (the UK, France, Russia for the Ottoman Empire, Russia for Bulgaria), or over them. The “Great Game” assured an audience for “compellence via proxy” and the 1878 Treaty of Berlin provided the legal framework for justifying such intervention.

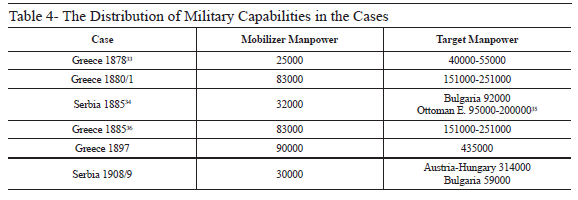

What about “weakness”? Table 4 summarizes the distribution of military capabilities (in manpower) between mobilizers and their targets. In the Greece 1878 case, Greece can be considered a “weak” actor compared to the Ottoman Empire. While it is true that the Ottomans were reeling from the blows of the Russian Army in the 1877-1878 war, the Greek army was rather small compared to the forces available to the Ottomans by 28th January 1878. Furthermore, the imminent Russian armistice meant that additional troops would be able to confront the Greek invasion. Thus the Greek gamble was predicated on being able to get the Russians (still at war with the Ottoman Empire) or other Great Powers to accept a fait accompli, before the Ottomans were able to react. They failed, as the Russians ignored the Greeks, and the other Great Powers were interested in shoring up the Ottoman Empire after its defeat and thus refused to support Greece. The Ottomans were able to credibly threaten war on Greece once peace was made with the Russians. In 1880/1, 1885 and 1897 Greece was considerably weaker than the Ottoman Empire. Indeed in 1897 the Ottomans fought with a partial mobilization. Consequently Greece acted from a position of “weakness”.[32]

In 1885 Serbia would not seem a weaker actor against Bulgaria. On paper the Serbian army in full mobilization could number 135,000 men. This force dwarfed the combined armies of the two Bulgarian principalities. However two conditions severely weakened Serbia. Serbian mobilization could trigger a war with the Ottoman Empire, the suzerain of the Bulgarian principalities, which could mobilize a much larger army than Serbia, and had standing forces that in combination with the vassal armies of the Bulgarian Principalities would outstrip a fully mobilized Serbian army. More crucially King Milan I of Serbia decided to go for a partial rather than full mobilization, thus only putting to the field 32,000 men.[37] The decision was a political one and this rendered the Serbians a “weak” party. In 1909 both Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria had standing armies that were more numerous than that of Serbia. Both could also mobilize more troops than Serbia as evidenced by mobilizations in 1912-1913. Thus in 1908-1909 Serbia was a “weak” actor.

(It may seem interesting that I did not choose the cases with a thought to whether they fit the concept of “weakness”. Rather, I chose them to fit the concept of availability of third party potential interveners. You should choose case studies based on the independent variable or conditions most likely to see the rise of the relationship you expect. But never choose them on the dependent variable, the outcome. If you chose cases on the dependent variable you are essentially selecting those cases where the outcome was present or absent, which raises issues of selection bias. This means that any relationship you found could have been the result not of the independent variable but other variables associated with the presence or absence of the dependent variable, which you have missed, due to choosing based on the presence or absence of the dependent variable. Choosing cases based on other variables or the independent variable is less likely to suffer from selection. Actually preferably you should choose them by random lot. However this can be hard when information is not equally available for all possible cases.)

We can thus argue that, more or less, all six cases fit the concept of “compellence via proxy”. This is corroborated by the long duration of the period between mobilization and war for the cases were war happened, and the long duration of the crises that did not lead to war (with the exception of the 1878 Greek case, where demobilization was almost immediate). The long periods were the results of waiting for great power intervention. In many cases the diplomatic character of the mobilizations was explicit. King Milan of Serbia, in the 1885 case, in his 1st October 1885 “speech from the throne” expressed his willingness to accept the union of the Bulgarian principalities if Serbia was compensated territorially. Milan’s unwillingness to mobilize fully for war, a move that would antagonize the Ottomans, and his rescinding of the 27th October 1885 order to cross the frontier due to the November Constantinople Conference, are two indicators of this attitude. Further supporting is the fact that he only declared war and invaded after the Great Powers in the Constantinople Conference refused to accommodate Serbian interests.[38]

In 1909 the Serbians again demanded compensation.[39] Once more the mobilization was explicitly part of a bargaining strategy that simply failed to work in the face of German support for Austria, and the unwillingness of Russia to fight a war for Serbia without the support of France and the UK. The Greek mobilizations of 1880, 1885 and 1897 were explicitly declared as parts of a diplomatic strategy to get the Great Powers to “listen” to Greek demands.[40] Indeed in 1880/1 one could say that Greece was the executor of the decision of the Great Powers as expressed in the Treaty of Berlin. The exception is 1878, when Greece tried to bring about a “fait accompli” with the invasion of Domokos. An element of this exists in 1897 when the sending of the Vassos Expeditionary Force to Crete was an attempt to bring the great powers before a “fait accompli”.[41]

(The long duration between mobilization onset and either war onset or crisis termination is the warrant we have for the argument that these mobilizations were probably part of a “compellence via proxy” strategy. The long duration undermines their potential “private” character, and largely negates any military advantage. Thus the only rational option, excepting domestic goals, is that these are bargaining tools. That said, documentary evidence that decision makers explicitly made this connection is always welcome.)

The above narrative and the findings of Table 3 show how much of a gamble attempts at “compellence via proxy” are and the reasons why they might fail. Of the six cases, only the Greek 1880/1 case was a success in that it both avoided war and led to immediate diplomatic gains. All other cases were failures. Two of the failures saw the eruption of war and the defeat of our “gamblers”. What is more, in 1878, 1885, 1897, and 1908/9 Greece and Serbia were pursuing goals that were inimical to the positions on the issues of some, or all the major powers. Indeed in two cases, 1878 and 1897, Greece tried to bring the powers before a fait-accompli! Only in the 1880/1 case was Greek action in accordance with Great Power goals. It is thus evident that “compellence via proxy” can only work when it is in pursuit of goals tolerable if not facile for the third parties one wishes to bait.

(There is always a question about how deeply to look at your case studies. This largely depends on the role of the cases studies in your multi-method analysis, and the variables you are looking at. It also depends on who the intended audience is. The easier to proxy with quantitative variables or with clear indicators of narrative support, the less deep you have to be in the analysis. The more abstract the concepts at stake the deeper the analysis you will need. The more the audience is used to deep analysis (for example historians or anthropologists) the deeper your analysis must be. Normally “motivation” is the type of abstract concept that requires a deep analysis. However, i) the proxy of duration of mobilization to war onset or crisis termination, and ii) the role of the qualitative analysis as auxiliaries to the large-n study, make it more likely that the reader might accept a lighter look at the cases. Again, readers, question, and goal are the absolute determining factors on not just what methods to use, but also how to use them.)

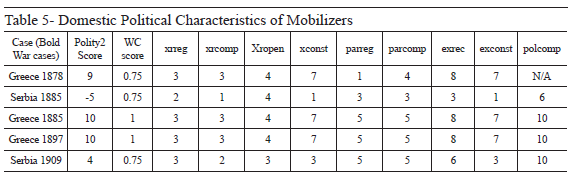

The next question is why were Greece in 1878,1885 and Serbia in 1908/9 able to avoid war once their attempt at “compellence via proxy” failed, while they failed to do so in 1897 for Greece and 1885 for Serbia? Table 5 summarizes the information on the domestic politics of the two actors in the cases, based on data from Polity IV, and the Bueno De Mesquita et al Winning Coalition data.

On first view, the information in Table 5 corroborates the null findings of the large-n study. There do not seem to be any clear patterns of association between domestic politics variables and the dependent variable. While in the Serbian case there seems to be an association between a more “liberal” political system, as captured by Polity variables, and the avoidance of war, the Greek cases belie such an association. In neither case does the size of the winning coalition seem to matter. This corroboration of the large-n studies does seem to reinforce the view that the relationship between domestic politics and the failure to avoid war after a failed attempt to trigger “compellence via proxy” cannot be located in the role of the size of the winning coalition. But it would be wrong to totally discount domestic politics. The qualitative analysis can unearth some elements that might be important but were missed by the large-n study.

There are similarities between the Greek and Serbian political systems. Both systems were based on the mediated political participation of masses via competitive elections between parties united around individual politicians, heading patronage networks. In Greece those networks tended to be localist, while in Serbia they tended to be clan based. In both cases the state apparatus was a spoil used to reward voters, and one of the main tools for social mobility.[42]

But there were important differences. The franchise in Greece covered almost all adult male Greeks, while it was more restricted in Serbia. Education in Greece was more widespread, and the political class more confident. As the data in Table 5 shows, Serbia had a much more powerful sovereign than Greece had. This was especially the case during the reign of King Milan I. We can also see this by comparing the number of prime ministers that changed during the crises as noted in Table 3. Milan I did not change his prime minister in 1885. Compare this with the ministerial changes in the 1908/9 crisis. The liberalization of Serbia between 1885 and 1909, and especially the increase of restrictions on the ability of the sovereign to pursue options in foreign policy, does seem to be a difference between the outcome of the 1885 and 1908/9 crises.[43] Whether this difference is crucial is an open question. The Greek case does not permit us to resolve this, as in general, George I was a scrupulous constitutional monarch, especially after 1876.

Another domestic characteristic that cannot be captured by the large-n study is the role of nationalist conspiratorial societies in the politics of the two Balkan states. A difference between the 1878, 1880/1, and 1885 crises and the 1897 crisis for Greece was the activity of the conspiratorial society of the National Association (Ethniki Hetaireia/Εθνίκη Εταιρεία). This organization, created in 1894, by 1896 had a wide membership that pervaded the army and civil service and was active in supporting or fermenting Greek revolutionary activity in Crete and Macedonia. It also acted as a focus for civil society pressure on the government, one that was in general hardline.[44] Many contemporary observers and analysts blame the National Society for the inability of the Greek government of 1897 to back down from the steps to war.[45] Thus the inability of the Greek government to step back from war in the 1897 crisis is probably associated, to a certain degree, with the presence of the National Association. However no general rule can be brought out by this case, because the Serbian cases have contrasting conditions.

In 1885 King Milan was an absolute ruler who faced few checks and balances. There was no domestic conspiratorial network to limit his options. More important is the 1908/9 case. Ever since the bloody overthrow of King Alexander Obrenovich in 1903, Serbian decision makers had to operate under the fear of political assassination and the conspiratorial influence of the clique of regicide officers, organized around Dragutin Dimitrijevich (aka Apis of 1914 fame). Furthermore, in 1908 in reaction to the Bosnian annexation, a mass organization like the Greek National Association, the Serbian National Defense (Srpska Narodna Obdrana) was organized to apply pressure on the decision makers to go to war.[46] But unlike the Greek case of 1897, the Serbian decision makers were able to overcome those pressures and avoid war.

(The above qualitative findings could be connected to the idea of overhauling winning coalitions a bit more. But since there is no clear relationship, as was the case with the large-n study, a decision was made to save space.)

The analysis of the cases above corroborates the statistical findings. It does not seem that winning coalition dynamics have a great influence on whether a state that attempts to trigger “compellence via proxy” is able to avoid war when that attempt fails. That is not to say that domestic politics do not play a role. The Greek 1897 case and the Serbian 1885 case both indicate an importance of domestic conditions. But what exactly is the more general causal role of domestic politics requires further study.

8. Conclusions

In this study I endeavored to add to the rationalist literature on the role of “public” mobilization in coercive bargaining. I focused on a specific empirical manifestation of “public” mobilization, mobilization with the goal of triggering “compellence via proxy”. In this instance a “weak” actor uses mobilization to trigger a crisis with a “stronger” adversary, with the goal of bringing about intervention by even stronger third parties in the hope that the final resolution will accommodate the stakes in the issue of the initial mobilizer. The main empirical question I focused on here is why, when such attempts to trigger “compellence via proxy” fail, some of the actors are able to back down from the steps to war which their actions have led them to, while others fail to do so and become embroiled in a dis-advantageous war.

To answer the above question I developed explanatory stories about the conditions under which states might try to bargain via “compellence via proxy”, why such conditions are rife with failure, and why when failure happens some governments are able to avoid escalation, while others are not. The explanatory story focuses on the dynamics between the winning coalition and the elites in government which rely on them to rule. The expectation was that the easier that it is for elites in government to overhaul their winning coalition, the easier it would be to execute complete reversals of policy and step away from war.

To evaluate this relationship I decided to focus on multi-method research design. I chose two methods I had become familiar with during my MA and PhD studies, and which are fairly simple to use. This was because of the combination of paucity of ready-made mobilization data, the expectation of a curvilinear relationship, and the lack of secondary sources on cases. I thus used a cross-tabulation large-n study model in conjunction with a broad overview of six Balkan mobilizations in the 1878-1909 period. While each of the two methods on its own would be a shallow evaluation of the question, in conjunction they provided consistent and robust results. These results were that there is no clear relationship between size of the winning coalition, the independent variable, and war onset after “compellence by proxy” failure, the dependent variable.