James M. Scott

Texas Christian University

Brandy Jolliff Scott

Texas Christian University

Since the end of the Cold War, advanced democracies have enacted explicit strategies of democracy promotion by providing assistance to governments, political parties, and other non-governmental groups and organizations all over the world. This paper examines the factors shaping European Union democracy aid allocation decisions from 1990-2010, weighing the relative impact of ideational concerns (regime type, human rights) and self-interests (political, security, economic). We argue that EU democracy aid reflects a “democracy-security dilemma” as the EU balances ideational reasons for promoting democracy with concerns over political and economic relationships, regional stability, and security. We test our hypotheses with a series of random effects, generalized least squares and Heckman selection models, which provide support for our argument. The paper concludes with a discussion of the implications of these findings for the impact and explanation of EU democracy promotion policies.

1.Introduction

After the Cold War, developed democracies in North America and Europe sought to promote democracy around the world, with democracy aid as a central component their efforts. Informed in part by the democratic peace literature,[1] observers and policymakers alike regularly identified such efforts as a goal combining ideational and strategic/security concerns. As Art argued, supporting democracy is a compelling goal because “democracy is the best form of governance; it is the best guarantee for the protection of human rights and for the prevention of mass murder and genocide; it facilitates economic growth; and it aids the cause of peace.”[2] However, as a scarce resource, democracy assistance is allocated selectively: some otherwise similar states receive substantial commitments of democracy aid while others receive little or none. How do aid allocators decide where to commit democracy assistance?

To explain the distribution of democracy aid, we argue that donors face a democracy-security dilemma: ideational reasons for promoting democracy are weighed against political, economic, and security/stability interests, all of which may be threatened by democratization. Not only do some potential democracy aid recipients have relationships and preexisting agreements with donors that advance donor security interests, but situational factors related to recipient political context, conflict, and other matters also influence the desirability, efficacy, and potential consequences of democracy aid. In practice, efforts to promote democratization, develop and sustain friendly neighbors and neighborhoods, build security, and maintain stability are at times at odds. We argue that this dilemma, and its balancing, help to account for the patterns of democracy aid distribution.

To test our democracy-security dilemma argument, we examine global European Union (EU) democracy aid allocations from 1990-2010 to examine the democracy-security dilemma and its effects on EU democracy assistance.[3] Specifically, we ask: How has the EU translated the democracy-security dilemma in the practice of democracy aid globally in the 1990-2010 period? Our focus is on EU assistance, not aid from individual EU member states, which is justified for a variety of reasons. Not only is the EU a significant player in global democracy promotion,[4] but EU aid is separate from the foreign aid budgets and decisions of member states. The European Commission is in charge of EU foreign aid: foreign aid priorities and packages are determined by the Commission’s Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development and aid policy-making at the Commission-level is separate from that of member states.[5] Finally, EU democracy aid represents a “hard test” of our democracy-security dilemma argument, since ideational objectives should be more salient in EU aid decision-making than in the decisions of EU member states or other donors such as the US, whose national interests should be relatively more prominent.

We first set the context of foreign aid and then focus on democracy aid, laying out the democracy-security dilemma. We argue that the EU balances ideational reasons for promoting democracy with concerns over economic relationships, stability, security, and the potential consequences of regime change, with the balance point tilting toward interests/security over ideational preferences for democracy. We then model EU democracy aid allocations as a function of donor interests, recipient characteristics, and situational factors, weighing the tradeoffs that affect and help to explain the allocations. We conclude with the implications for EU democracy assistance and the democracy-security dilemma.

2. The EU and the Foreign Aid-Democracy Aid Context

Foreign assistance goals range from the selfless to the selfish,[6] and donors weigh and balance factors such as recipient economic needs and humanitarian concerns with donor economic, political, strategic, and security interests, the latter of which are typically more important to donor allocation decisions.[7] As Palmer et al. bluntly conclude, “donors expect political benefits from their aid.”[8]

For example, during the Cold War, the bipolar system and the ideological contest between the US and Soviet Union shaped general foreign aid strategies and allocations, and the balance point among competing goals generally favored security concerns.[9] European foreign aid provisions heavily favored aid relationships with former colonies. The promotion of neoliberal economic reforms was a particular priority, as characterized best by the various Lomè Conventions beginning in 1973 and continuing into the 1990s, and the subsequent formation of the ACP (African, Caribbean, Pacific) Partnership, including many former British, French, German, Belgian, and other member state colonies.[10]

After the Cold War, donor interests adjusted to emphasize strategies and tactics to assist and integrate members of the former Soviet bloc, to pursue economic relationships and opportunities, and to emphasize ideational goals such as human rights and democracy to a greater extent than previously, thus shifting the balance point in the democracy-security dilemma toward democracy.[11] In this context, the EU continued to expand its foreign aid and development focus to a wider range of state recipients beyond former European colonies. With the signing of the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, the European Commission (EC) specifically began targeting aid for the promotion of democracy and human rights through the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), one aim of which was to promote regional integration as a means to achieve economic growth and peace and security objectives.

Donor interests after 2001 reflected elevated security concerns about Islamic radicalism and the threat of terrorism and political instability in the context of the Global War on Terror, shifting the balance point between democracy and security back toward security.[12] For the EU, the threat of terrorism prompted a rethinking of previous aid strategies and a concerted effort to enhance the coordination, quantity, and quality of aid between the Commission and the member states. The EU adopted the European Consensus on Development in 2005, with increased attention to poverty reduction, democracy, and good governance in recipient states.[13]

Democracy assistance is a subcategory of foreign economic aid, and it consists of small, targeted packages designed to support various democratization projects: elections; supporting political institutions such as legislatures, courts, and political parties; and grassroots aid that supports civil society organizations, civic education, and the media.[14] Beyond support for elections and democratic institutions, such aid often bypasses regime officials to assist groups and implement projects directly or through third parties.[15] According to Tierney et al., by the end of the 20th century, the US and other foreign aid donors devoted an expanding share of their foreign assistance budgets to democracy aid, reaching 10-15% of allocations by 2000.[16]

The end of the Cold War elevated the strategic and normative importance of promoting democracy and spurred greater interest in democracy assistance as donors adapted to the changing international environment.[17] In Europe, democracy promotion became official EU policy with the 1992 Maastricht Treaty on European Union. Article 21 of the Treaty states:

The Union's action on the international scene shall be guided by the principles which have inspired its own creation, development and enlargement, and which it seeks to advance in the wider world: democracy, the rule of law, the universality and indivisibility of human rights and fundamental freedoms, respect for human dignity, the principles of equality and solidarity, and respect for the principles of the United Nations Charter and international law.[18]

Maastricht established the CFSP, with Article 21.2.b stating the goal to “consolidate and support democracy, the rule of law, human rights and the principles of international law.” In response, in 1994 the EU set up the European Initiative for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR) with a budget of 59.1 million ecu, which grew to over €1 billion by 2016.[19]

The EU expanded its democracy promotion efforts after the Cold War. In 1995, the EU initiated the Barcelona Process with its eastern and southern neighbors. While the main beneficiaries of Barcelona were eastern European countries seeking EU membership, the overall project was a step toward making the Maastricht declarations more than just rhetoric. In 2006 the European Consensus on Development carried a specific focus on the promotion of “democratic values” and promised significant increases in aid to developing countries:

The Community development policy will have as its primary objective the eradication of poverty in the context of sustainable development, including pursuit of the MDGs, as well as the promotion of democracy, good governance and respect for human rights, as defined in part I (European Consensus on Development 2006).[20]

Then, in 2011 the EU issued its Agenda for Change, stating that:

recognizing that good governance, in its political, economic, social and environmental terms, is vital for inclusive and sustainable development, the EU support to governance shall feature more prominently in all partnerships. The EU action should center on the support and promotion of democracy, human rights and the rule of law, gender equality, civil society and local authorities…

The importance placed on the promotion of democracy by the EU rests on the role democratic values played in making “Europe” peaceful and prosperous. This experience led to broad support for enshrining democracy promotion as a core aim of evolving EU common foreign policy endeavors. Additionally, the EU generally views democracy promotion as an avenue for creating security in insecure places, linking “democracy, human rights, development, and good governance in a virtuous package that will eradicate the root causes of conflicts, failed states, illegal immigration, and terrorism.”[21]

3. Democracy Aid and the Democracy-Security Dilemma

Analyses of democracy aid have studied its effects and the determinants of its allocation. With respect to its effects, unlike general foreign aid, which has not been shown to promote democratization,[22] a growing body of literature finds that targeted democracy aid does have positive effects on democratization and its survivability.[23] Evidence also indicates that the choice of recipient and democracy aid type is important to the success of democracy aid.[24]

Analyses of democracy aid allocations are generally informed by the complex calculations around foreign aid allocations. Overall, a variety of determinants shape foreign aid allocations, including recipient development and humanitarian needs; recipient regime characteristics and human rights behavior; colonial legacies; various situational factors, including economic crises, conflict and political changes; donor security/political/economic interests; and political and economic bargaining between donors and recipients.[25] Explanations of democracy aid allocations have built on foreign aid literature to emphasize the role of donor interests, situational factors, recipient need and other characteristics, and ideational factors such as human rights in allocation decisions.[26] Like studies of foreign aid more generally, analyses of democracy aid allocations are informed by the fact that donors have many potential target recipients and limited democracy aid resources to allocate. For both foreign aid and democracy aid, donor interests appear to influence allocation decisions consistently.[27]

The insights of these previous studies lead us to our argument: ideational motives for democracy assistance collide with other considerations, especially political, economic and security/stability concerns. The nexus of these concerns establishes a democracy-security dilemma for donors like the EU, resulting in trade-offs between two valued outcomes. The spread of democracy is in the interests of donors such as the EU because, in general, a more democratic world likely offers greater opportunity to resolve differences and conflicts via peaceful mechanisms, and because the policy goals and political practices of democratic states tend to be more consistent with donor preferences.[28] However, while support for democracies may reflect those interests, regime transitions have also been feared for their potential impact on stability and may threaten donor security interests. In practice, this creates tension between promoting democracy and pursuing political/security interests.[29] Because of the strategic importance of stable relations with a potential recipient, political, economic and security interests, and concerns for stability weigh heavily on democracy aid allocators.[30] Consequently, we argue that donors such as the EU may be skeptical of movements away from autocracy and cautious about providing democracy assistance, since recipient democratization may not lead to increasingly similar interests with donors and may also threaten existing security relationships.

To understand the democracy-security dilemma in practice, consider the illustration of North Africa, which represents a good example of the dynamics of the democracy-security dilemma. As a region in which democracy has failed to take root, North Africa might initially appear to warrant democracy promotion by donors such as the EU. However, security concerns have often incentivized accommodation and support of these authoritarian regimes. Exacerbating this, democracy promoters in the EU grapple with the absence of effective (or receptive) civil society organizations in the states of the region, which limits their use of a common avenue of democracy assistance. Moreover, this limit is compounded by the nature of opposition groups themselves, with the goals of Islamist groups central to this concern. Consequently, donors face questions of whether or not they should exert pressure on North African governments to liberalize/democratize at the risk of jeopardizing relations, complicating the pursuit of other security goals, and generating instability in which potentially hostile Islamist groups gain power.

This democracy-security dilemma manifested itself immediately as the 1995 EU Barcelona Process set up the European-Mediterranean Partnership (EMP) to establish an area of “peace, prosperity, and security” with 12 eastern European, Mediterranean, and North African countries. Barcelona and the resulting EMP were created to use the attractiveness of and conditionality for potential EU membership to compel economic liberalization and democratization.[31] However, the EU Commission and EU member states shared a concern that promoting democracy in the region could lead to greater instability: “Political liberalization was, they maintained, now seen as the best means of engendering both stability and moderation in the Mediterranean,” but, “No EU member state maintained that the democracy promotion agenda should, in the case of the Mediterranean, contain any aspiration to undermine incumbent regimes.[32]

Follow-on initiatives such as the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP), established in 2003-04 both to build and improve upon the EMP, reflected concerns apparent under the EMP and favored economic reform over political reform, especially with respect to the North African members.[33] Further, after the events of September 11, 2001 and the subsequent Islamic terrorist attacks in Madrid in 2004 and London in 2005, the EU grappled with the democracy-security dilemma in the changing context. In the wake of 9/11 and the European terrorist attacks, the EU tended to downgrade the importance of democratization in favor of security and counter-terrorism, a fact which seemed to only confirm to the authoritarian regimes of the region the relative unimportance of democracy promotion when compared to the strategic interest of stability and peace.[34]

Building on the literature and the North Africa example, we argue that the democracy-security dilemma affects EU approaches to democracy promotion globally in ways that are consistent with the general finding of the foreign aid allocation literature: “donors expect political benefits from their aid.”[35] We therefore expect both ideational and interest/security factors to be relevant to EU democracy aid allocations. However, guided by previous scholarship and seen through the lens of the democracy-security dilemma, we expect these sometimes-contending factors to balance in favor of the security end of the dilemma, especially when the forces of democratization potentially undermine key interests of the donor. In effect, we argue that the EU will de-emphasize democracy aid to avoid the risk of destabilizing a regime and/or the relationship it has with the EU. Consequently, if security/interests dominate, we hypothesize that five related manifestations of that tilt exist.

Previous studies emphasizing the importance of donor interests lead us to this trade-democracy aid link, which rests on the premise that the EU prefers stability with trade partners to protect economic ties. As a result, the EU de-emphasizes democracy aid to its trading partners, since democratization may threaten the regime’s stability and thus the economic relationship with the recipient country.

Previous studies emphasizing the importance of donor interests lead us to this link between political affinity/interests and democracy aid, which rests on the argument that recipients in which the EU has greater political affinity/interests are preferred targets for democracy aid, in part because such aid preserves rather than threatens stability in the relationship.

As previous literature indicates, donors like the EU have interests in stability in their aid targets. Because the EU is concerned with stability, potential recipients experiencing conflict are less preferable as targets of democracy aid. The conflict itself reduces the potential efficacy of democracy aid and such unstable environments constitute risky targets.

As in hypothesis 3, because the EU is concerned with stability and reluctant to invite terrorist attacks on EU member states, potential recipients experiencing terrorism are less preferable as targets of democracy aid.

Previous studies indicate that the nature of a potential aid recipient’s regime affects democracy aid allocations.[36] If EU democracy aid reflected democracy promotion purposes, we would expect it to be directed to less democratic regimes to encourage and support democratization. However, because we argue that concerns for stability and security are more important, we expect the EU to target more/already democratic regimes, thus supporting democracy rather than risking destabilization and disruption of less democratic regimes.

4. Data and Methods

In sum, we argue that EU democracy aid allocations reflect a balance point in the democracy-security dilemma that favors EU interests and security concerns. To examine the democracy-security dilemma and its impact on global EU democracy assistance allocations we study country-year EU democracy aid to 127 countries from 1990-2010. For our dependent variable, EU democracy aid, we rely on the AidData 2.1 dataset.[37] We select assistance from the EU and aggregate it to the annual, country-level commitments by purpose, differentiating between democracy assistance and other development aid with the AidData 2.1 project codes. We identify purpose codes 15000-15199 as democracy assistance, and all others as general foreign aid. In our analysis, we consider both the annualized sum of democracy aid to a recipient state and a dichotomous variable differentiating between democracy aid recipients and non-recipients. On the former, we take the logarithm of democracy aid in constant 2009 dollars.[38]

To gauge the concern for the democracy end of the democracy-security dilemma, we measure regime type/condition with Polity IV data,[39] while acknowledging its limitations.[40] The 21-point Polity2 variable is a composite score ranging from -10 (least democratic) to 10 (most democratic), with interregnum and transition scores (-77, -88) replaced with scores of 0 and interpolated scores respectively to reduce missing data, and interruption (-66) scores designated as missing values. If democracy is important, we expect a negative relationship between Polity score and EU democracy aid, as the EU targets less democratic regimes for democracy promotion, while a positive relationship would reflect greater concern for stability, as the EU targets more democratic regimes for support rather than less democratic regimes for democratization.

We include four variables to gauge the role of political, economic and security/stability interests on EU democracy aid allocations.[41] First, for political interests, we measure the foreign policy affinity between recipient states and the EU using United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Voting Data.[42] We measure the affinity of recipient countries with EU member France as a proxy for the EU.[43] Many studies highlight the tendencies of the EU’s powerful countries to use their foreign aid budgets to influence recipient states.[44] Affinity is measured using the yearly s3un measure between France and all recipients. In this measure, ranging from -1 to 1, higher scores represent similar voting and thus, we argue, similar political interests—between France and a recipient. If political/strategic interests of member states dominate EU democracy aid allocations, we expect a positive relationship between affinity and democracy aid.

Second, for economic interests, we include trade between a potential recipient and Germany, relying on this as a proxy measure for trade with the European Union as a whole. Germany is the world’s third largest exporter, German exports comprise over 25% of all exports from EU countries, and over 6 million German jobs rely on the export of goods and services with non-EU importers. Given the dominance of the German economy when it comes to EU trade and the extensive role Germany has historically had in spearheading EU economic policy, we believe trade with Germany to be a useful proxy for trade with the EU as a whole. [45] We log the sum of imports and exports, in constant 2009 US dollars, between Germany and each potential recipient. The dyadic data we use to measure trade come from the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) Direction of Trade Statistics. We expect the EU to allocate lower levels of democracy aid to countries with higher levels of trade with the EU, as measured by dyadic trade with Germany.

For stability/security interests, we include two additional variables. We gauge the effect of conflict on EU democracy aid allocations, relying on the Major Episodes of Political Violence data from the Center for Systemic Peace.[46] For each country-year, from this data we identify countries involved in on-going conflicts in a dichotomous variable. In addition, we include a measure for instances of terrorism, relying on the University of Maryland’s Global Terrorism Database.[47] For the period 1990-2010, we aggregate this data to annual country-year counts of the incidents of terrorism. If security/stability concerns dominate the democracy-security dilemma, we expect a negative relationship between these measures and democracy assistance.

Controls. We include five controls in our models. To capture recipient economic need, we include annual per capita gross domestic product (GDP) in current dollars for each country, derived from the Penn World Tables. We control for the effect of colonial relationships with a dichotomous measure indicating (0) if the recipient is not a former colony of a European state and (1) if the recipient country is a former colony of a European state, relying on the ICOW Colonial History Data Set.[48] Because the EU has special political and economic relationships with certain states around the world, we control for the impact of two agreements on EU democracy aid allocations: the European Neighborhood Partnership (ENP) and the African, Caribbean, and Pacific States Economic Partnership Agreement (ACP EPA).[49] To account for these relationships, we use dichotomous measures for membership in each agreement. The variables are coded (0) if a country is not a member of the ENP or ACP and (1) if the country is a member.[50] Finally, to control for the impact of general aid commitments on democracy aid allocations, we subtract EU democracy aid from total EU aid to obtain a measure of “other EU aid,” and include its logarithm in constant 2009 dollars.[51]

We conduct our empirical tests in three ways. We begin with simple descriptive and bivariate data to outline democracy aid patterns and trends across the period. Then, we test our argument with a generalized least squares AR(1) model with random effects, appropriate to the time-series cross-sectional data of our study.[52] For our analysis, random effects estimators have the advantage of taking into account both the uniqueness of each country and the effect of time. Unlike fixed effects, this technique controls for effects that are unique to country but constant over time and those that are constant across countries but vary over time.[53] To account for the autoregressive process in the dependent variable (democracy aid), we follow Achen, Drury and Peksen, Rudra and others and apply a standard AR(1) estimator to correct for this process.[54] We lag all independent variables by one year to ensure time order.

Finally, we model the impact of selection effects on EU democracy aid allocations. It is common to model foreign aid decisions as a two-step process to account for selection effects, as some states do not receive aid. In such models, states must pass through the selection stage to be considered for certain amounts of economic and military aid. Thus, aid allocations are subject to censoring and recipients constitute a non-random sample; failure to account for this results in biased estimates.[55] In our data, about 40% of the country-year cases receive no democracy assistance, so modeling a selection effect is appropriate.

Like others,[56] we apply Heckman selection models to aid allocation to control for potential selection bias.[57] The Heckman model estimates a maximum likelihood model for the first stage (selection), producing a nonselection hazard rate (inverse Mills ratio). At the second stage, an OLS model is applied and the nonselection hazard rate is added as a variable to account for the nonrandom sample. Estimates at the second stage are thus consistent and unbiased and reflect the impact of the nonselection hazard rate. To properly identify the model, we rely on the exclusion restriction, by which at least one variable is present in the first stage but not the second stage. For our tests, we model the recipient’s economic need (per capita GDP) as the exclusion variable in the selection.[58] We include a lagged dependent variable and lag all our independent variables by one year to ensure proper time order. All results are derived from STATA, version 15.

5. Results

The balance of the evidence indicates that the EU responds to the democracy-security dilemma in ways that are largely consistent with our argument. Overall, EU tradeoffs between ideational and security concerns favor interests/security. Despite the ideational rhetoric, commitments, and concerns, EU democracy aid allocations are best explained as a function of the dominance of the security end of the democracy-security dilemma. We first present descriptive information about EU democracy aid and then discuss the results of our tests.

5.1. EU democracy assistance in context, 1990-2010

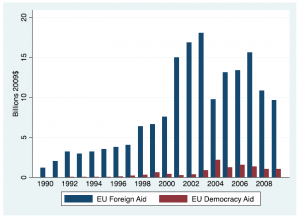

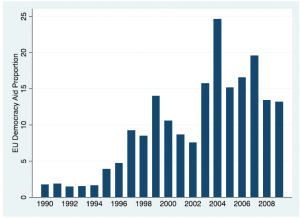

To begin, Figures 1-2 provide context for our analysis. Figure 1 presents EU allocations of democracy aid and general foreign aid from 1990-2010. As the figure shows, foreign aid rose steadily in the 1990-2010 period, while limited amounts of democracy aid began in the early 1990s, increasing in 1997-1998. After a surge in 2004, EU democracy aid held relatively steady through 2010. Figure 2 presents evidence on democracy aid as a proportion of total EU aid, again extending back to 1973 to provide long-term context. For the EU, democracy aid remained at less than 5% of EU assistance until 1996, increased to 5-10% of foreign aid in the latter post-Cold War years, and then increased to more than 12% of foreign aid consistently in the Global War on Terror years after 2002. Together, Figures 1-2 indicate that democracy aid emerged as a significant global strategy for the EU after the end of the Cold War.

Figure 1: EU Foreign and Democracy Aid, 1990-2010 (constant 2009 $)

Figure 2: EU Democracy Aid, 1990-2010 (constant 2009 $)

5.2. Explaining EU democracy aid and the impact of the democracy-security dilemma

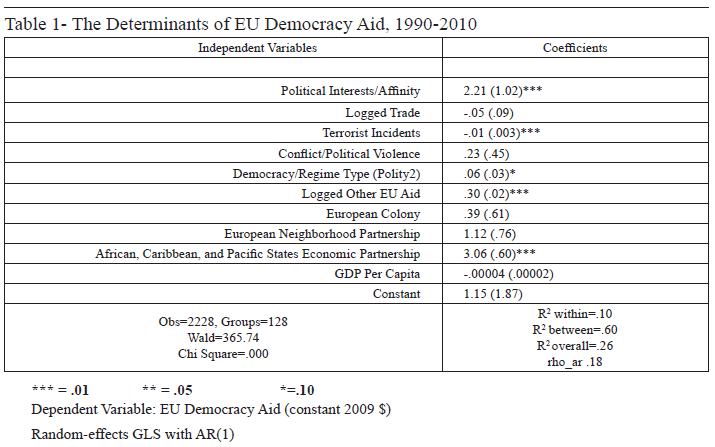

Given this context, how does democracy-security dilemma affect EU democracy aid? Table 1 presents the first test of our model/argument, a generalized least squares technique with controls for an AR(1) process. The results support three of the five hypotheses of our argument. Overall, these results indicate that the democracy-security dilemma pushes EU democracy aid allocations to favor EU interests and security concerns over democracy.

First, the results support two of the four hypotheses focused on interests/security. Hypothesis 1 receives support, as potential recipients with whom EU political interests/similarity are high receive dramatically more democracy aid than other recipients. A shift of 1 from -0.5 to +0.5 on the political interests/affinity scale is associated with about 10.8% more democracy aid from the EU, which is the largest effect for any factor in the model. Consistent with Hypothesis 4, potential recipients experiencing terrorist strikes receive less democracy aid than other recipients, reflecting the described security/stability concerns. The results indicate that every 10 terrorist incidents in a potential recipient state reduces democracy aid by about a half a percent. The results in Table 1 do not support Hypotheses 1 or 3 however. Neither trade (Hypothesis 1) nor conflict/political violence (Hypothesis 3) is a statistically significant factor in EU democracy aid allocations.

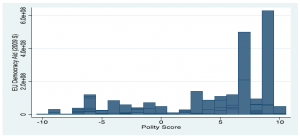

The results in Table 1 also provide support for Hypothesis 5, indicating that democracy aid allocations are guided by cues in recipient democracy/regime type that are consistent with a tilt toward the interests/security end of the democracy-security dilemma. Table 1 shows the EU democracy aid targets already more democratic regimes rather than less democratic ones. This is not consistent with a democracy promotion purpose but, rather, with a preference for security/stability, as we suggest in Hypothesis 5. The results indicate that each 1-point shift toward greater democracy is associated with about 0.30% more democracy aid. This means that countries at the democratic end of the scale receive about 3-5% more democracy aid than countries at the lower end. To further illustrate this effect, Figure 3 shows the distribution of EU democracy aid (in 2009 $) across the Polity2 scale. This figure clearly shows that countries with the greatest democracy deficit (or, greatest democratic demand) receive much less EU democracy aid, while already democratic regimes (Polity2 scores of 7-10) receive much more. If the EU were attempting to promote democratization, the opposite should be the case.

Figure 3: EU Democracy Aid and Democracy/Regime Type, 1990-2010 (constant 2009 $)

Finally, these results hold after controlling for other factors, many of which reinforce the importance of EU interests. Other EU aid and membership in the ACP are positively associated with more democracy aid, while colonial relations with the EU, membership in the European Neighborhood Partnership, and per capita GDP are not statistically significant factors. Although we did not hypothesize about these controls, we note that both other EU aid and membership in the ACP may also be interpreted as indicators of broader political and economic interests, so these results also lend general support for our overall argument. It is also notable that ENP membership does not induce greater democracy aid. We note also that the null findings on colonial relationships as a factor shaping allocations runs counter to other foreign aid research.[59]

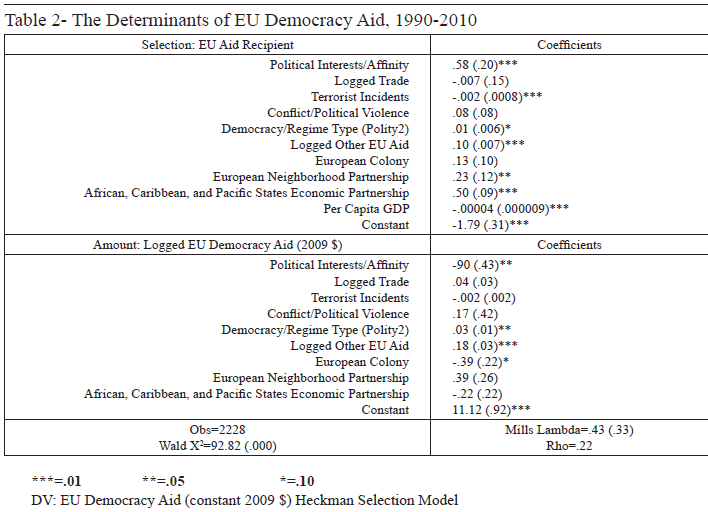

Table 2 presents the second test of our model/argument, employing a Heckman selection model to account for selection effects. The results in Table 2 are consistent with those in Table 1 and provide further evidence in support of our overall argument. These results provide support for three of our five hypotheses.

Table 2- The Determinants of EU Democracy, 1990-2010

Two of the four hypotheses focused on interests/security again receive support in the results in Table 2. Hypothesis 2 receives support, as political interests/affinity are positively associated with greater likelihood of receiving democracy aid at the selection stage. Interestingly, however, while the EU selects countries with greater political affinity to receive democracy aid, once past that selection screen, democracy aid is directed toward those with less affinity. Hypothesis 4 also receives support, with incidents of terrorism negatively associated with democracy aid at the selection stage. Neither Hypothesis 1 nor Hypothesis 3 is supported by the results of this test: trade and conflict/political violence are not statistically significant at either the selection or the amount stage.

Hypothesis 5 is supported as well. The democracy/regime type measure is statistically significant at the selection and amount stages, showing that more democratic regimes are both more likely to receive EU democracy aid, and to receive greater amounts. At the amount stage, a 1-point shift toward democracy is associated with about .15% increase in democracy aid; countries at the democratic end of the scale receive 1-2% more democracy aid than those at the autocratic end. Again, this is not consistent with a democracy promotion purpose.

Our control variables show results generally consistent with those in Table 1, though more of them are statistically significant. In Table 2, all controls are statistically significant at one or both stages. Recipient economic need, as measured by per capita GDP, increases the likelihood of receiving democracy aid (selection stage). Membership in the European Neighborhood Partnership and membership in the ACP are positively and significantly associated with EU democracy aid at the selection stage. Other EU aid positively and significantly affects EU democracy at both the selection and amount stages. Finally, less EU democracy aid is directed to former European colonies (amount stage) than other potential recipients. As noted earlier, these results may also be interpreted as further evidence of the impact of political and economic interests on EU democracy aid allocations.

6. Conclusion

What explains the selective allocation of EU democracy aid? We have theorized that the need to balance principles and interests generates a democracy-security dilemma that helps to explain democracy aid allocations and, especially, the conditions under which such aid is directed to the promotion of democracy. Our evidence indicates that the democracy-security dilemma leads the EU to balance ideational reasons for promoting democracy with political, economic, security and stability concerns in such a way that the balance point tilts toward security over democracy. Our tests model EU democracy aid allocations as a function of donor interests, recipient characteristics, and situational factors and support our argument. Although our evidence does not provide uniform support for all our hypotheses, it substantially supports four of the six we derive from our argument, partially supports a fifth, and, overall, suggests that political and security/stability interests are particularly powerful factors when the EU gives democracy aid.

Broadly speaking, our findings contribute to the foreign aid-democracy aid literature studying aid allocations and suggest that translating declaratory policy of democracy support into practice is challenged when such commitments collide with other considerations, especially political, economic and security concerns. When such concerns are present, political and security interests appear to trump ideational/democratization commitments, exposing a gap between rhetoric and reality when it comes to promoting democracy. Concerns over established relationships and preexisting agreements that advance donor security interests, desires to develop and sustain friendly neighbors and neighborhoods, and the need to build security and sustain stability are sometimes at odds with interest in and efforts to promote democratization. When they are, it appears the balance point on the democracy-security dilemma tilts in favor of security. This core finding from our analysis sheds light on the sometimes-contradictory findings of previous studies and indicates how ideational and interest-based concerns intersect in democracy aid allocations.

Our evidence also raises important questions about current challenges facing democracy promotion, with recent anti-democratic trends especially important. As the stability of democracy worldwide is challenged, should we expect the provision of democracy aid to respond in kind? Or given the appearance of anti-democracy trends even within traditional democracy aid donors in both Europe and North America, might we expect to see the provision of democracy aid worldwide trend downwards as well? How will the balance between principles and interests in democracy aid allocation be affected by these changes? Perhaps even the fundamental premise of democracy aid is changing entirely as a result of the need to balance principles and interests. Our results suggest that democracy aid may be less about supporting “democratization” per se, and more about reinforcing and supporting stability in existing democratic states. If this is the case, then might we expect to see significant shifts in global democracy aid allocation trends and a noticeable reduction of the willingness of donors to allocate aid to semi-democratic states undergoing democratization?

Finally, our analysis suggests some intriguing routes for further study. For one, the possibility that donors work to complement or supplement each other in a kind of democracy promotion network in which different donors specialize in different approaches or areas warrants attention. Also, comparative analysis of democracy aid by the EU and its individual member states offers promising insights on a range of issues, such as whether EU member states balance the democracy-security dilemma differently in their national foreign aid programs and to what extent the democracy promotion goals of member states are used to influence democracy aid programs at the EU level. Furthermore, are there regional variations in the effects of the democracy-security dilemma on democracy aid allocations such that the balance point between principles and interests vary by different regions? Additionally, foreign policy context matters as well,[60] and the balance point on the democracy-security tradeoff may well shift according to that context. Thus, disaggregating the time period into sub-periods to reflect changing contexts, problems, and prospects might reveal a more dynamic process and variation in the relative importance of interest-based and ideational factors in those different sub-periods. Finally, our analysis suggests that the potentially reciprocal relationships between democratization, democracy promotion, and democracy aid merits further study of its own.

Since the end of the Cold War, democracy promotion has been embraced by the EU and most other Western donors as an important foreign policy strategy that combines ideational and strategic/security concerns. In practice, however, the simple and powerful rationale behind democracy aid[61] tangles with other interests, often generating the need for trade-offs. EU democracy aid since 1990 reflects those trade-offs, driven by a “democracy-security dilemma” as it balances ideational reasons for promoting democracy with concerns over political and economic relationships, regional stability, and security. The balance appears to favor interests.

James M. Scott, Department of Political Science, Texas Christian University. Email: j.scott@tcu.edu. ORCID https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7415-9506

Brandy Jolliff Scott, Department of Political Science, Texas Christian University. Email: b.jolliffscott@tcu.edu. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2642-6515

Achen, Chris H. “Why Lagged Dependent Variables Can Suppress the Explanatory Power of Other Independent Variables.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Political Methodology Section of the American Political Science Association, University of California at Los Angeles, July 2000.

Alesina, Alberto, and Dollar, D. “Who Gives Foreign Aid to Whom and Why?” Journal of Economic Growth 5 (2000): 33–63.

Apodaca, Clair, and Michael Stohl. “United States Human Rights Policy and Foreign Assistance.” International Studies Quarterly 43 (1999): 185–98.

Art, Robert J. A Grand Strategy for America. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 2003.

Arvin, Mak B., and Torben Drewes. “Are There Biases in German Bilateral Aid Allocations?” Applied Economics Letters 8, no. 3 (2001): 173–77.

Askarov, Zohid, and Hristos Doucouliagos. “Does Aid Improve Democracy and Governance? A Meta–regression Analysis.” Public Choice 157 (2013): 601–28.

Balla, Eliana, and Gina Y. Reinhardt. “Giving and Receiving Foreign Aid: Does Conflict Count?” World Development 36 (2008): 2566–585.

European Union. Barcelona Declaration. Adopted at the Euro-Mediterranean Conference. November 11,1995. https://ec.europa.eu/research/iscp/pdf/policy/barcelona_declaration.pdf.

Beck, Nathaniel. “Time-Series-Cross-Section Methods.” In Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, edited by Janet Box-Stefeensmeier, Henry E. Brady, and David Collier. London: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Beck, Nathaniel, and Jonathan N. Katz. “Time-Series-Cross-Section Issues: Dynamics.” Unpublished paper, 2004. http:⁄⁄www.nyu.edu⁄gsas⁄dept⁄politics⁄faculty⁄beck⁄beck_home.html#Research.

Berk, Richard A. “An Introduction to Sample Selection Bias in Sociological Data.” American Sociological Review 48 (1983): 386–97.

Berthelemy, Jean–Claude. “Bilateral Donors’ Interest vs. Recipients’ Development Motives in Aid Allocation: Do All Donors Behave the Same?” Review of Development Economics 10, no. 2 (2006): 179–94.

Blanton, Shannon Lindsey. “Foreign Policy in Transition: Human Rights, Democracy, and U.S. Arms Exports.” International Studies Quarterly 49 (2005): 647–67.

Boone, Peter. “Politics and the Effectiveness of Foreign Aid.” European Economic Review 40, no. 2 (1996): 289-329.

Boschini, Anne, and Anders Olofsgard. “Foreign Aid: An Instrument for Fighting Communism.” Journal of Development Studies 43 (2007): 622–48.

Boutton, Andrew, and David B. Carter. “Fair Weather Allies: Terrorism and the Allocation of US Foreign Aid.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 58, no. 7 (2014): 1144–173.

Brautigam, Deborah A., and Stephen Knack. “Foreign Aid, Institutions and Governance in Sub–Saharan Africa.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 52 (2004): 255–85.

Bridoux, Jeff, and Milja Kurki. Democracy Promotion: A Critical Introduction. London: Routledge, 2014.

Burnell, Peter. Democracy Assistance: International Cooperation for Democratization. London: Frank Cass, 2000.

———. “Political Strategies of External Support for Democratization.” Foreign Policy Analysis 1 (2005): 361-84.

Bush, Sunn. The Taming of Democracy Assistance: Why Democracy Promotion Does Not Confront Dictators. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Carbone, Maurizio. The European Union and International Development: The Politics of Foreign Aid. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Cingranelli, David L., and Thomas E. Pasquarello. “Human Rights Practices and the Distribution of US Foreign Aid to Latin American Countries.” American Journal of Political Science 3 (1985): 539-63.

Collins, Stephen D. “Can America Finance Freedom? Assessing U.S. Democracy Promotion via Economic Statecraft.” Foreign Policy Analysis 5 (2009): 367-89.

Cox, Michael, Timothy J. Lynch, and Nicolas Bouchet. US Foreign Policy and Democracy Promotion: From Theodore Roosevelt to Barack Obama. London: Routledge, 2013.

Crawford, Gordon. “Whither Lome? Mid-Term Review and the Decline of Partnership.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 34 (1996): 503-58.

Dietrich, Simone. “Bypass or Engage? Explaining Donor Delivery Tactics in Foreign Aid Allocations.” International Studies Quarterly 57, no. 4 (2013): 698-712.

Dietrich, Simone. “Donor Political Economies and the Pursuit of Aid Effectiveness.” International Organization. 70 (2016): 65-102.

Dietrich, Simone, and Joseph Wright. “Foreign Aid Allocation Tactics and Democratic Change in Africa.” Journal of Politics 77 (2015): 216–34.

Dixon, William J. “Democracy and the Peaceful Settlement of International Conflict.” American Political Science Review 88 (1994): 14–32.

Doyle, Michael W. “Liberalism and World Politics.” American Political Science Review 80, no. 4 (1986): 1151-1169.

Drury, A. Cooper, and Dursun Peksen. “Coercive or Corrosive: The Negative Impact of Economic Sanctions on Democracy.” International Interactions 36, no. 3 (2010): 240–64.

Drury, A.Cooper, Richard Olson, and Douglas Van Belle. “The CNN Effect, Geo-strategic Motives and the Politics of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance.” Journal of Politics 67 (2005): 454-73.

Eur-Lex. Summaries of European Legislation: MEDA Program (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM%3Ar15006), accessed February 19, 2019.

European Commission. The European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights, 2016. https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/how/finance/eidhr_en.htm

European Commission. “Relations with the EEAS, EU institutions and Member States.” https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/relations-eeas-eu-institutions-and-member-states_en.

European Union. European Consensus on Development. Official Journal of the European Union 2006/C 46/01.

European Union. Treaty on European Union, 1992. https://europa.eu/european-union/sites/europaeu/files/docs/body/treaty_on_european_union_en.pdf.

European Union External Action Service. “European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP)”. December 21, 2016.

https://eeas.europa.eu/diplomatic-network/european-neighbourhood-policy-enp/330/european-neighbourhood-policy-enp_en.

Fariss, Christopher J. “The Strategic Substitution of United States Foreign Aid.” Foreign Policy Analysis 6, no. 2 (2010): 107–31.

Fink, Günther, and Silvia Redaelli. “Determinants of International Emergency Aid-Humanitarian Need Only?” World Development 39, no. 5 (2011): 741–57.

Finkel, Steven E., Aníbal Pérez–Liñán, and Mitchell A. Seligson. “The Effects of U.S. Foreign Assistance on Democracy–Building, 1990–2003.” World Politics 59 (2007): 404–39.

Fleck, Robert E., and Christopher Kilby. “Changing Aid Regimes? US Foreign Aid from the Cold War to the War on Terror.” Journal of Development Economics 91 (2010): 185–97.

Green, Donald P., Soo Yeon Kim, and David H. Yoon. “Dirty Pool.” International Organization 55, no. 2 (2001): 441–68.

Heckman, James J. “The Common Structure of Statistical Models of Truncation, Sample Selection and Limited Dependent Variables and a Sample Estimator for Such Models.” Annals of Economic and Social Measurement 5 (1976): 475–92.

———. “Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error.” Econometrica 47 (1979): 153–61.

Heinrich, Tobias. “When is Foreign Aid Selfish, When Is It Selfless?” Journal of Politics 75, no. 2 (2013): 422–35.

Heinrich, Tobias, and Matt W. Loftis. “Democracy Aid and Electoral Accountability.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 63 (2017): 139–66.

Heinrich, Tobias, Yoshiharu Kobayashi, and Leah Long. “Voters Get What They Want (When They Pay Attention): Human Rights, Policy Benefits, and Foreign Aid.” International Studies Quarterly 62 (2018): 195–207.

Hensel, Paul R. “ICOW Colonial History Data Set, version 1.0.” 2014. http://www.paulhensel.org/icowcol.html.

Joffe, George. “The European Union, Democracy and Counter-Terrorism in the Maghreb.” Journal of Common Market Studies 46 (2007): 147–71.

Jolliff Scott, B. “Explaining a New Foreign Aid Recipient: The European Union’s Provision of Aid to Regional Trade Agreements, 1995-2013.” Journal of International Realtions and Development. (2018). doi: 10.1057/s41268-018-0163-z.

Kalyvitis,Sarantis, and Irene Vlachaki. “Democratic Aid and the Democratization of Recipients.” Contemporary Economic Policy 28 (2010): 188–218.

Kelley, Judith. “New Wine in Old Wineskins: Promoting Political Reforms through the New European Neighbourhood Policy.” Journal of Common Market Studies 44 (2006): 29–55.

Kersting, Erasmus, and Cristopher Kilby. “Aid and Democracy Redux.” European Economic Review 67 (2014): 125–43.

Knack, Stephen. “Does Foreign Aid Promote Democracy?” International Studies Quarterly 48 (2004): 251–66.

Lai, Brian. “Examining the Goals of US Foreign Assistance in the Post–Cold War Period, 1991–96.” Journal of Peace Research 40 (2003): 103–28.

Lebovic, James H. “National Interests and US Foreign Aid: The Carter and Reagan Years.” Journal of Peace Research 25 (1988): 115–35.

Lumsdaine, David H. Moral Vision in International Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Marshall, Monety. “Major Episodes of Political Violence (MEPV) and Conflict Regions, 1946–2015.” Center for Systemic Peace, May 25, 2016. http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscr/MEPVcodebook2015.pdf

Marshall, Monty G., and K. Jaggers. “Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800–2010.” (2011) http://www.systemicpeace.org/polityproject.html.

Maoz, Zeev, and Bruce M. Russett. “Normative and Structural Causes of the Democratic Peace, 1946–1986.” American Political Science Review 8, no. 3 (1993): 624–63.

McKinlay, Robert D., and Robert Little. “A Foreign Policy Model of Us Bilateral Aid Allocation.” World Politics 30 (1977): 58–86.

McLean, Elena. “Donor's Preferences and Agent Choice: Delegation of European Development Aid.” International Studies Quarterly 56 (2012): 381–95.

Meernik, James, Eric L. Krueger, and Steven C. Poe. “Testing Models of U.S. Foreign Policy: Foreign Aid During and After the Cold War.” Journal of Politics 60 (1998): 63–85.

Mitchell, Lincoln A. The Democracy Promotion Paradox. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2016.

Mitchell, Sara McLaughlin. “A Kantian System? Democracy and Third–Party Conflict Resolution.” American Journal of Political Science 46, no. 4 (2002): 749–59.

Munck, Gerardo L., and Jay Verkuilen. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy: Evaluating Alternative Indices.” Comparative Political Studies 35 (2002): 5–35.

National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). “Global Terrorism Database [Data file], 2016.” https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd.

Neumayer, Eric. The Pattern Of Aid Giving: The Impact of Good Governance on Development Assistance. London: Routledge, 2005.

Nielsen, Richard. “Rewarding Human Rights? Selective Aid Sanctions against Repressive States,” International Studies Quarterly 57 (2013): 791–803.

Nielsen, Richard, and Daniel L. Nielson. “Triage for Democracy: Selection Effects in Governance Aid.” Paper presented at the Department of Government, College of William & Mary, February 5, 2010.

Palmer, Glenn, Scott B. Wohlander, and T. Clifton Morgan. “Give or Take: Foreign Aid and Foreign Policy Substitutability.” Journal of Peace Research 39 (2002): 5–26.

Peterson, Timothy, and James M. Scott. “The Democracy Aid Calculus: Regimes, Political Opponents, and the Allocation of US Democracy Assistance, 1981–2009.” International Interactions 44, no. 2 (2018): 268–93.

Pinto-Duschinsky, Michael. “Foreign Political Aid: The German Political Foundations and Their US Counterparts.” International Affairs 67, no. 1 (1991): 33-63.

Qian, Nancy. “Making Progress on Foreign Aid.” Annual Review of Economics 7 (2015): 277–308.

Reinsberg, Bernhard. “Foreign Aid Responses to Political Liberalization.” World Development 75 (2015): 46-61.

Rudloff, Peter, James M. Scott, and Tyra Blew. “Countering Adversaries and Cultivating Friends: Indirect Rivalry Factors and Foreign Aid Allocation.” Cooperation and Conflict 48, no. 3 (2013): 401–23.

Rudra, Nita. “Globalization and the Strengthening of Democracy in the Developing World.” American Journal of Political Science 49 (2005): 704–30.

Russett, Bruce Martin. Grasping the Democratic Peace: Principles for a Post–Cold War World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Schraeder, Peter J., Steven W. Hook, and Bruce Taylor. “Clarifying the Foreign Aid Puzzle: A Comparison of American, Japanese, French, and Swedish Aid Flows.” World Politics 50 (1998): 294–323.

Scott, James M., and Carie A. Steele. “Sponsoring Democracy: The United States and Democracy Aid To The Developing World, 1988–2001.” International Studies Quarterly 55, no. 1 (2011): 47–69.

Scott, James M., and Ralph G. Carter. “Distributing Dollars For Democracy: Changing Foreign Policy Contexts and The Shifting Determinants of US Democracy Aid, 1975–2010.” Journal of International Relations and Development (2017). doi : 10.1057/s41268–017–0118–9.

Scott, James M., and Ralph G. Carter. “From Cold War to Arab Spring: Mapping the Effects of Paradigm Shifts on the Nature and Dynamics of U.S. Democracy Assistance to the Middle East and North Africa.” Democratization 22, no. 4 (2015): 738–63.

Scott, James M., and Ralph G. Carter. “Promoting Democracy in Latin America: Foreign Policy Change and US Democracy Assistance, 1975–2010.” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 2 (2016): 299–320.

Smith, Karen. “The Role of Democracy Assistance in Future EU External Relations.” Paper presented at the European Conference on Enhancing the European Profile in Democracy Assistance, the Netherlands, 4-6, July 2004.

Tierney, Michael J., D. L. Nielson, D.G. Hawkins, J. T. Roberts, M. G. Findley, R. M. Powers, B. Parks, S.E. Wilson, and R. L. Hicks. “More Dollars than Sense: Refining Our Knowledge of Development Finance Using AidData.” World Development 39, no. 11 (2011): 1891–906.

Voeten, Erik, Anton Strezhnev, and Michael Bailey. “United Nations General Assembly Voting Data.” 2009, hdl: 1902.1/12379, Harvard Dataverse, V17. UNF:6:o5OiqHLeXMiv9Q8w8+3sVw==.

Youngs, Richard. “The European Union and Democracy Promotion in the Mediterranean: A New or Disingenuous Strategy?” Democratization 9 (2002): 50-62.

———. The European Union and the Promotion of Democracy: Europe’s Mediterranean and Asian Policies. London: Oxford University Press, 2002.