Şevket Ovalı

Dokuz Eylül University

İlkim Özdikmenli

Dokuz Eylül University

Growing anti-Western sentiments around the world are currently manifesting themselves through divergent ways ranging from peaceful resistance movements to various forms of political violence. In the Middle East, unlike the earlier partially secular and nationalist Cold War anti-Americanism, the current popular anti-Western political movements are heavily equipped with Islamism, which appears to be an all-inclusive ideology and political movement for almost all dissidents. This applies to Turkey as well, despite its relatively long history of secularisation. This research particularly aims therefore to discuss the role of nationalism and Islamism on anti-Western sentiments in Turkish foreign policy through the lens of neo-classical realism and a new, broader conceptual framework: The Western Question. The research examines the contours, contents, and consequences of the problem through comparing two cases, namely the Cyprus problem of the 1970s and the crisis with the West that has surfaced after Turkey’s involvement in the Syrian Civil War.

1.Introduction

Even before the establishment of modern Turkey in 1923, modernization had been closely associated with the so-called Western model and the ‘West’ had appeared for at least a century to be the most convenient and unrivalled model. The Western model had deep impacts not only on the restructuring of the Turkish state and society but also on the country’s foreign policy orientations. While the Western inspired reforms have faced formidable challenges and even reversals in domestic politics especially after the 1950s, the Western orientation has remained mostly untouched in the domain of foreign policy as manifested in the country’s aligning with the West for over 50 years regardless of the ruling parties’ ideological orientations. Yet in the history of Turkey there are certain moments of estrangement from the West, which are dramatically different from other cases of policy divergences between Turkey and major Western powers. In this study, the term “Western Question” is offered to refer to those unique moments in the history of relations between Turkey and the Western world.

The Western Question refers to strategic considerations in Turkish foreign policy in the form of a recurrent pattern which usually manifests itself among policy circles through severe criticism of the country’s alignment with the West. In this regard, the phrase “West” is assumed to address a broader political, economic, and cultural context rather than a robust geographical demarcation. With reference to the lexicon of Turkish politics, the term West is basically used interchangeably but in a disjunctive way to describe the USA and Western European states as well as their common values and institutions.

In order to understand Turkey’s “Western Question”, one must know the historical roots of the Turks’ somewhat ‘schizophrenic’[1] perception of the West, which involves both a quest for belonging to the Western civilization and a deep unease about the Western powers’ imperial agenda. Cultural transfers from Europe to Ottoman society started in the early eighteenth century, and were soon institutionalized and extended to non-military spheres. Nevertheless, this accelerated ‘Westernisation’ in the nineteenth century was accompanied by the peripheralization of the Ottoman state in the European economy and politics. Resentment towards the gradual loss of sovereignty and the fear of collapse began to grow even among the intellectual/political current known as ‘Batıcılar’ (pro-Western group).[2] The Treaty of Sèvres, which partitioned Ottoman territory amongst Western major powers and local groups supported by them, made this fear a reality in 1920. Although it was soon rendered invalid, the psycho-political legacy of the treaty remained and was passed on to later generations, known as the ‘Sèvres Syndrome’.[3] It was frozen until the 1960s, at first because of mutual protectionist policies and Turkey’s successful avoidance of European political problems during the interwar years and World War II, and then because of the fervour of involvement in the “free world” in face of perceived threats from the Soviet Union. The alignment with the West soon started to produce significant bilateral problems due to power asymmetry, but structural entanglements and legal treaties in economic, military and political fields restrained Turkey from taking any sustainable radical action. Nevertheless, the fear and suspicion continued to exist and at times it was deliberatively operationalized by policymakers.

What makes the Western Question in Turkish foreign policy different from the occasional crises that arise, lurks in its particular characteristics. First, it goes beyond a single-issue conflict to comprise a set of complicated, distinct but at the same time inter-related issues. Second, contrary to the narrow bilateral problems, it involves more than one actor; e.g. the EU, US, NATO, which makes the problem much more difficult to resolve. Third, compared with the occasional short-term disagreements, it is an enduring impasse that is likely to produce unexpected consequences from time to time. Finally, unlike other issues on the agenda of Turkish foreign policy, it mobilizes the electorate around the ruling parties through the excessive use of an anti-Western rhetoric and thereby creates a rally-around-the-flag effect.

Two periods in Turkish-Western relations, the Cyprus crisis of 1974-1980 and the Syria crisis of 2011-2017, are revisited in this study as instances of the Western Question. The context of the former crisis dates back to the 1960s, when the perennial state of emulation and suspicion towards the West had resurfaced. The US had gained a great freedom of action on Turkish soil in the 1950s on the pretext of defending Turkey,[4] but this was resented and being actively challenged by Turkish public opinion in the 1960s. While anti-Americanism was at the outset exclusively an ideological element of the orthodox socialist movements, it soon gained a crosscutting character. It is plausible to argue that nationalism with an anti-imperialist tone, unleashed by the de-colonization wave of the 1960s, had appealed mainly to the leaders and the parties on the left wing of the political spectrum. On the other hand, this ideology also served as an escape valve for the right-wing parties to avoid electoral pressures, particularly on issues of national interest. Even though Schweller[5] defines ideology as a domestic variable, we argue that the national and international ideational contexts cannot be separated from each other, and formulating ideology solely as a domestic intervening variable would be to miss the Zeitgeist of the 1970s in the Middle East. Since anti-imperialist nationalism embedded in a national developmentalist economic and political framework was the all-inclusive ideology of the Middle East until the end of the 1970s, Turkey’s Western Question has also been resurrected around it.

After the 1980s, political Islam consolidated itself as the main ideological equipment of Anti-Western movements in the Middle East. Despite the resistance of secular military and civilian elites, the moderate Islamist AKP’s (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, Justice and Development Party) electoral success in 2002 was a remarking victory in Turkey and the party’s accomplishments inspired all other Islamic parties in the MENA region. Unsurprisingly, for the purpose of reducing the power of the military, which was necessary for the party to consolidate its power after 2002, the AKP pursued a pro-Western foreign policy in its early years. Following its victory in the 2011 elections, the tide gradually turned against the West and an anti-Western foreign policy discourse with an Islamic tone not only manifested itself in the foreign policy choices of the elites but also became an instrument to mobilize the masses and for extracting the country’s resources. Unlike the anti-imperialist secular nationalism of the 1970s, the Western Question in Turkish foreign policy has been resurrected around Islamic nationalism.

The steadily growing literature on Turkish foreign policy has addressed growing anti-Westernism in various ways and has no doubt made relevant contributions to our understanding of Turkey’s future relations with the West. In the case of Turkey’s deteriorating relations with the EU, for instance, de-Europeanization became an analytical tool for researchers and provided insights into the policy implications of this specific phenomenon[6]. In addition, Turkey’s disenchantment with the West and its ‘unruly’ engagement in the Middle East have also dominated scholarly debates in recent years, with this literature mostly focusing on whether such a move can be interpreted as an axis shift or activism seeking to produce political and economic escape valves for strained relations with the West[7].

If Turkey’s ongoing commitments to NATO and the EU as well as Ankara’s longstanding partnerships with the West are considered, framing the problem as an axis shift produces a distorted narrative and remains counterintuitive in this context. On the other hand, de-Europeanization, as a conceptual framework, lacks the transatlantic dimensions of the problem, and remains mostly incapable of explaining the complex dimensions of the problem. The Western Question as a concept offers a broader framework with a special emphasis on the intricate web of geopolitical conflicts, policy divergences and relations.

Yet, it is still necessary to explain why some crises but not others (such as the rejection of sending Turkish troops to Iraq in 2003) ended up with deeper estrangement. This is why we analyse these instances of the Western Question by employing neo-classical realism. It helps us to reveal the ideational context of disputes without disregarding systemic imperatives. Neo-classical realism, with its emphasis on the role of both systemic incentives and intervening unit level variables, provides an insight for examining the influence of domestic intervening variables such as the state structure, state-society relations, elites’ perceptions on Turkey’s relative power and their immediate responses/foreign policy behaviours to systemic pressures through the lens of an ideational context in which these intervening variables operate. Additionally, neo-classical realism primarily focuses on why states react differently to similar systemic incentives and therefore Turkey’s different reactions to similar systemic incentives fits well to this theoretical framework.

Within this scope the study falls into four sections. First, the theoretical and conceptual framework is introduced. The way that neo-classical realism brings together the role of systemic incentives and the power of ideas is explored in order to understand two instances of the Western Question. The next section examines the causes and trajectory of the first of these instances, the Cyprus crisis, which led to considerable policy change and strife between Turkey and the West between 1974 and 1980. In the section that follows, a currently resurrected Western Question in the aftermath of the Syrian Civil War is dealt with. After these two descriptive sections, the last section comparatively analyzes the cases in terms of systemic factors, ideational context, domestic intervening variables and their impacts on short-term foreign policy behavior as well as long-term policy outputs. Hypotheses developed through an application of neo-classical realism are thereby tested. The article concludes with our findings regarding the nature of the Western Question and predictions about the future of relations between Turkey and the West.

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

A neo-classical realist approach to foreign policy analysis necessitates the examination of the domestic and individual level variables as well as systemic level ones, since the former seem to cause different state responses to similar systemic incentives. According to Talieferro, Lobell and Ripsman[8] ‘neoclassical realism builds upon the complex relationship between the state and society found in classical realism without sacrificing the central insight of neorealism about the constraints of the international system’. In other words, neo-classical realists stress the primacy of the systemic imperatives in determining the foreign policies of states, but they also incorporate domestic and individual level variables into their analysis[9]. However, in the final analysis, as Kitchen[10] argues, ‘such variables are considered analytically subordinate to systemic factors, the limits and opportunities of which states cannot escape in the long run’.

Borrowing the main argument of neorealism, neo-classical realism argues that states’ foreign policy outputs are dependent on their relative material power capabilities. Yet, as Devlen and Özdamar[11] argue, ‘although in the long run relative power capabilities may determine foreign policy outcomes, foreign policy behaviour may not reflect those underlying structural constraints in the short term’. In this regard, neoclassical realism does not only provide an explanatory insight on states’ short term foreign policy behaviours, but also unveils the ‘transmission belt linking material capabilities to foreign policy behaviour’[12].

The process of linking relative material power capabilities to foreign policy behaviour is completed by two interrelated unit level variables: First, the actual elites/leaders and their perceptions of the system and their states’ relative powers;[13] and second, domestic structures which could limit or enable the leaders for using, extracting and mobilizing the state’s resources for their foreign policy objectives.[14] Such an approach to foreign policy analysis clearly raises the necessity of exploring the effects of ideologies or ideas on the elites’ responses/foreign policy behaviours to the systemic incentives[15] because ‘strategic beliefs exist more in the realm of ideology than in that of pure cognition’.[16] Neo-classical realism’s interest in the role of leaders and the power of ideas are borrowed from classical realism[17] and in this manner it aims to explain how the ideational context filters the threat perceptions, relative power capabilities and foreign policy outputs.

Understood as such, the central question of neo-classical realism on the role of ideational factors in foreign policy choices is formulated by Rippsman, Talieferro and Lobell[18] as follows: “Given the causal primacy of systemic (material) variables, under what conditions are collective ideational variables at the unit level more likely to play an intervening role between systemic pressures, on the one hand, and the specific foreign and security strategies states pursue at a given time?”

Similarly, the following excerpt from Kitchen[19] also underlines the role of ideas in the neo-classical realist approach to foreign policy;

A theory of ideas however, whilst incorporating these insights about the character of domestic politics, focuses on how prevailing ideas influence the type of foreign policy response to structural imperatives. It can therefore explain how similarly structured states may respond in different ways to similar threats by reference to differing prevailing ideas within the state, whether that be as a result of the particular individuals advocating the ideas, broader cultural preferences, national history or whatever. The response as understood through the prism of ideas can then account for both overreaction and underreaction, as well as for the pursuit of goals unrelated to the notion of threat.

Ideas shape and drive the responses / policy behaviours to systemic incentives and they also appear to be one of the most significant instruments of foreign policy elites for extracting resources, increasing morale, constructing consent around the government, and legitimizing policy behaviours.[20]

The application of a neo-classical realist model of foreign policy therefore requires an examination of the role of ideologies on short-term foreign policy behaviors and the role systemic incentives have on long-term foreign policy outcomes. The application of a neo-classical realist model of analysis to the selected crisis reveals how the Western Question emerges and reconstitutes itself under different ideological contexts but with similar systemic incentives. Even though the structure of the international system/the independent variable is different in selected crises and time intervals, it is obvious that the structure produces similar pressures that eventually end up with Turkey’s long-term foreign policy outcomes, namely Ankara’s realignment with the West. In both of the selected crises, the ideational context, beyond any doubt, is decisive in Turkey’s formulation and implementation of its short-term policy responses, while the systemic incentives determine the long-term policy outcomes.

At this point it is noteworthy to mention the similarities and differences between neo-classical realism’s and non-conventional social constructivism’s emphases on the role of ideational context, or the subjective environment in which foreign policy decisions are assumed to be made. [21] Like neo-classical realism, non-conventional constructivism considers the role of the subjective environment as a significant factor that influences leaders’ perceptions of the world and themselves. Moreover, neo-classical realists and non-conventional constructivists also argue that the subjective environment; e.g. ideologies, religion, faith, culture, history and individual identities, even determine what constitutes national interest for a nation and what constitutes an existential threat.[22] The major difference between the two approaches is that while non-conventional constructivists prioritize the role of subjective environment in foreign policy decisions and outcomes, neo-classical realism argues that domestic intervening variables are likely to influence short term foreign policy behaviours that are subordinate to systemic incentives. The short-term foreign policy behaviours and long-term policy outcomes of the Ankara governments on the selected crises display the explanatory value of neo-classical realism in the realm of foreign policy analysis. Even though social constructivism could also offer insights to understanding Turkey’s ideological deviations from the confines of realpolitik, Ankara’s surrender to systemic imperatives makes neo-classical realism a much more valuable analytical tool in the last instance.

Throughout the history of modern Turkey, a monolithic portrayal of the West as an elusive partner rather than a reliable ally has become a self-fulfilling prophecy in times of crises in which Turkey’s interests diverge from those of its Western partners. However, none of those crises inflicted lasting damages, as the formidable challenges within the context of the Western Question are considered. Among the many conflicts between Turkey and the West, most of which were limited and superficial, two specific cases deserve to be addressed separately in terms of what we suggest calling the ‘Western Question’; the Cyprus problem and the Syrian Civil War. What makes these cases unique and more conspicuous than the other crises with the West could be found in their common characteristics, which should be examined in a broader context. First, both crises have culminated in Turkey’s engagement into armed conflicts. Second, they have eventually made Turkey’s alignment with the West highly questionable in domestic political circles and somehow contributed to the formation of a grand coalition around the government. Third, both crises have brought about Turkey’s rapprochement with the non-Western world and a reorientation of its foreign policy. Fourth, these two crises have evolved into protracted conflicts over the years and impelled Turkish decision makers to deal with multiple interconnected issues and multiple actors within the West. Fifth, both cases have been equipped with anti-Western ideological stances, namely a secular developmentalist nationalism that manifested itself in a highly anti-imperialist tone in the 1970s and as Islamist nationalism after the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War. Despite their differences, the common characteristics of these two cases directly point out the distinguishing features of the problem in Turkish foreign policy formulated as the Western Question.

The above-mentioned characteristics of the Western Question also reveal some questions that the following parts of the research should address. Why do some crises but not others instigate the Western Question, i.e. resurface Turkey’s primordial mistrust towards the West? Or, why does Turkey have occasional deep crises with the West despite ongoing structural entanglements and decades of formal alliances? We argue that an historical analysis based on the role of ideologies in their own contexts that is identical to each selected crisis can provide the reader with the answers. In this regard, the following sections on selected crises will not only address the roots and dynamics of the Western Question, but will also display the influence of ideology as a domestic intervening variable as well as the role of systemic incentives that forced Ankara to return to the confines of realpolitik.

3. Rise of the Western Question: From the Johnson Letter to the 1974 Cyprus Peace Operation

While frictions between Turkey and the US concerning US military installations and personnel started as early as 1960, it was the Johnson Letter that marked the beginning of an era of unrelenting suspicion towards the US on both the right and left wings of the political spectrum in Turkey. Violation of the consociational character of the newly established Cyprus Republic by Greek Cypriots and the escalating aggression against the Turkish Cypriots in 1963 had become a concern for Turkey. When the US government received reports about Turkey’s intentions to send troops to Cyprus for protecting the Turkish Cypriots, US President Lyndon Johnson sent a letter to Turkish Prime Minister İnönü in June 1964, patronizingly reminding Turkey of its obligations as a NATO member and threatening not to protect Turkey if this non-consensual act led to any involvement by the Soviet Union[23]. Upon this development, Turkey banned the use of bases on Turkish soil for reconnaissance planes in 1965[24], embarked on developing its economic and political relations with the Eastern Bloc and Third World countries, forced the US to revise some articles of the 1954 Status of Forces Agreement in Turkey’s favour, and forbid ‘off-site’ use of military bases with the Joint Defense Cooperation Agreement signed in 1969.[25]

It is important to state that the abovementioned anti-American decisions were made by the right-wing Adalet Partisi (AP, Justice Party) governments that ruled between 1965 and 1971. Although it would be a ‘left-of-centre’ politician—Bülent Ecevit—who would decide to intervene in Cyprus against American wishes in 1974, right-wing governments under Süleyman Demirel were going to play a certain role during the accumulation of tensions before 1974. It was his conservative and pro-NATO AP that signed an economic and technical cooperation agreement with the USSR on 26 March 1967.[26] Having already overdrawn its IMF quota and unable to receive loans from the West, Turkey finally positively replied to the USSR, which had been following a consistent non-forcible policy of developing friendly relations with Turkey and offering financial and technical assistance for industrial projects since the 1950s, in the hope of restoring Turkey’s confidence and encouraging it to limit American economic and political influence.[27] Demirel later conveyed that the US was quite uncomfortable with the treaty, and the US ambassador has asked him ‘if Turkey was changing axis’.[28]

The Demirel governments’ tense accommodation with the US were also linked to the rising tide of anti-American sentiments and protests against US military installations and personnel. The symbol of this anti-American mobilization was leftist university students’ protest against the visit of the US Sixth Fleet to İstanbul in 1968, in which some US sailors were thrown into the sea. When the US demanded from the Turkish government to ban opium poppy cultivation in Turkey in 1970 on exaggerated accusations about Turkish illegal producers’ role in the heroin trade, this further provoked anti-American sentiments, not only among the urban masses but also among the farmers.[29]

All these tensions that had been accumulating for two decades ended up with the emergence of a deep Western Question in 1974, triggered by domestic variables --the rise of the RPP to power, led by a new and assertive leader, Bülent Ecevit-- as well as an external variable, the military intervention in Cyprus. Following the general elections in October 1973, the left-wing Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi (CHP, Republican People’s Party) and the Islamist Milli Selamet Partisi (MSP, National Salvation Party), which had managed to become the second large party in the right-wing after the AP, established a coalition government. Both parties were advocating developing heavy industry and greater independence from the US. At the time of the intervention in Cyprus, the coalition government had already been in deep discord with the US because of its decision to revoke the opium ban on 1 July 1974.

On 15 July 1974 a military intervention in Cyprus, supported by Greece and by pro-enosis Greek Cypriots, took place. Five days later Turkey launched the ‘Cyprus Peace Operation’. The international community considered the initial phase of the intervention as a legitimate act arising from Turkey’s internationally recognized guarantor state status. However, as the Second Geneva Conference, which had been convened to discuss the political future of Cyprus, continued, Turkey launched a second operation on 14 August, during which it took control of about 40 per cent of the island. This act was harshly protested and regarded as illegitimate by most countries, including the US and Western European states.

Outcomes of the operation for Turkish foreign policy were devastating. The US Congress, already considering punishing the Turkish government for its recent position on the opium issue, imposed an arms embargo on Turkey despite objections from the US government. Arms sales to Turkey were halted in February 1975, and military credits worth $200 million were suspended[30]. In response, the Turkish coalition government led by Demirel unilaterally abolished the Joint Defense Cooperation Agreement and closed down US bases in Turkey except those working as NATO missions. The activities and rights of the remaining American personnel were curtailed[31]. The project of strengthening Turkey’s national defence capacity based on national sources already underway since the early 1970s was accelerated, and many national military investments such as the establishment of ASELSAN (Military Electronics Industries Inc.) in 1975 and İŞBİR (Power Generation Machinery Factory) in 1978 were made in a few years.

Under these conditions, Turkey began to look for greater flexibility and increased regionalization. A major foreign policy outcome of the crisis was a revitalisation of the Turkish-Soviet rapprochement that had been halted in the first half of the 1970s. According to Wallace, the USSR ‘courted Turkey with aid and with diplomatic support’, the latter referring to the Soviet position of not publicly condemning Turkey in the 1974 Cyprus dispute.[32] In 1976, a Joint Intergovernmental Soviet-Turkish Commission on Economic Cooperation, which would meet annually to discuss new projects and trade opportunities, was established. As a result, the trade volume between Turkey and the USSR surged. Both Turkish exports to and imports from the USSR tripled over the next years.[33]

An even more striking indicator of improved economic relations was the massive amount of credits. In 1978 Turkey was granted industrial development credits from the USSR, amounting to $1.2 billion, the second largest pledge that year by the USSR to a developing country.[34] Guan-Fu studied Soviet gross disbursement to non-socialist developing countries between 1965 and 1979 and found that Turkey received $3,188 billion in this period, which constituted 25 per cent of all Soviet disbursements.[35] On 23 June 1978, the Political Document on the Principle of Good-Neighbourly and Friendly Cooperation was signed, stipulating mutual respect for each other’s sovereignty and regimes.

Turkey did not intend to cut off its ties with the US and NATO after the embargo; yet nor did it spend much effort to repair the relations. The US government lifted the ban on commercial sale of arms in October 1975 and sought for restoring its installations through an agreement with Turkey. As the US government regained control over the Congress, the embargo was completely lifted on 12 September 1978. When the talks resumed in 1979, Turkey insisted on clear guarantees against the possibility of facing with an embargo again in the future.[36] In the meantime, Turkey rejected two US demands to use the İncirlik base for its acts against the Islamic revolution in Iran and did not allow for US U-2 reconnaissance flights over the USSR.[37] This show of muscle may have played a role in reaching an agreement with the US. The new Defence and Economic Cooperation Agreement, signed in 1980, was to be ratified by a cabinet decree after the coup in Turkey on 12 September 1980.

The wide reach of Turkey’s Western Question in this period may be observed in Turkey’s rift with the EEC. Protocols that regulated the parties' liabilities during the phase of 'transition' to the customs union had been signed in 1970 but Turkey did not take any meaningful steps towards customs union as all successive governments had doubts about conditions that might hinder the development of national industry.[38] ‘One famous leftist slogan of the day about the Common Market, as the EEC was commonly known at that time, was that “they are the ‘commons’ or ‘partners’ and we are the ‘market’”’.[39] Turkey’s trade deficit with the EEC rose, and its attempts to gain concessions in the textile and agriculture sectors as well as free movement for Turkish workers failed. The EEC’s severe reaction against Turkey’s intervention in Cyprus and its improved relations with Greece were other negative factors.[40] In this context, in October 1978 the CHP government suspended its obligations for association. Although the relations with Europe further deteriorated over the next decade because of the severe violation of human rights by the military regime, Turkey eventually realigned with the US in 1980.[41]

4. The Syrian Civil War and Resurrection of the Western Question

The outbreak of the civil war in Syria in late 2011 marked a new period in the history of Turkey’s relations with the West and the Western Question has been resurrected around this war. By early 2012, neither the US nor the EU was willing to start a new war in the Middle East. From the very early days of his administration, US President Obama declared his departure from traditional US foreign policy strategy; a retreat from expansion of the US role in world politics, shifting the focus from Europe to Asia and redefining global leadership on the basis of ‘economic competitiveness and diplomatic influence rather than military primacy’[42]. This posture manifested itself even after the allegations that the Assad regime had launched a chemical weapons attack in 2013 on the opposition forces. In the US President’s own words, the US was ‘not contemplating putting US troops in the middle of someone else’s war’.[43] Yet, DAESH (al-Dawla al-Islamiya fil Iraq wa al-Sham / The Islamic state of Iraq and the Levant) expansion in the region as well as Russia and Iran’s involvement in the Syrian civil war, forced the US administration to revise its strategy towards Syria.

By early 2014, how to cope with the growing DAESH threat without any large scale long term combat units or partners on the ground, was the most significant strategic problem facing the US and, given the group’s battlefield success against DAESH, a partnership with the YPG (People’s Protection Units), the Syrian branch of the terrorist organization PKK (Kurdistan Workers Party), appeared to be the most suitable alternative for achieving US interests. After the establishment of the SDF (Syrian Democratic Forces) in October 2015, an umbrella organization dominated by the YPG, cooperation between the YPG and the US military shifted to a regular basis, and from 2015 until early 2018 the US committed itself to arming the Syrian Kurds against DAESH. The tension between Washington and Ankara reached its peak on 14 January 2018, when the US announced the formation of an SDF-based border force in Syria to prevent the resurgence of DAESH. A few days later, Turkey announced the beginning of an extensive military offensive against the YPG controlled Afrin enclave in Syria.

Though the US-YPG partnership seems to be the main cause of the emerging Western Question in Turkish foreign policy, for Çağaptay,[44] ‘the honeymoon…ended in the summer of 2013’. The conflicting interests surfaced in May 2013 during the Obama-Erdoğan meeting regarding the future of Syria and the fate of the Assad regime, and strained relations rapidly evolved to the re-emergence of the Western Question with the involvement of much more complicated issues onto an agenda of already problematic relations. Without doubt, the clash between Turkish cleric Fethullah Gülen and then Prime Minister Erdoğan caused the tension-ridden Turkey-US relations to hit a new low point.

As the country’s Kemalist establishment was virtually eliminated after the AKP’s electoral victory in the 2011 elections, the disagreements between Gülen and Erdoğan swiftly surfaced. In 2012, the chief of the Turkish National Intelligence Agency, Hakan Fidan, was summoned by the Istanbul prosecutor to testify in an investigation on the PKK, as a suspect. Erdoğan’s response in 2013 was to announce the government’s decision to close down all prep schools that prepare students for the university exams. It was a major blow to the Gülen movement because those schools constituted a source of funds and recruitment for the movement.

The conflict evolved into an open war after the alleged corruption probe against Erdoğan’s family and three ministers in his government. Amid the corruption probe of December 2013, Erdoğan threatened to expel foreign ambassadors and blamed them for engaging in provoking actions against the government.[45] According to him, the entire corruption probe was a plot organized by the followers of Gülen in the judiciary and the police to topple a democratically elected government, and they were being supported by foreign powers. Finally, the failed coup organized by the Gülenist officers against the government in July 2016, sparked one of the most significant crises in Turkey-US relations, as Gülen was being given shelter by the US, and Turkey’s demands for his extradition were ignored by the US authorities.

Turkey’s Western Question in the aftermath of the Syrian Civil War is also associated with Ankara’s deteriorating relations with the EU since 2011. Whereas a massive exodus of Syrian refugees and Turkey’s sectarian pro-Islamist foreign policy in the MENA region were the main sources of discontent on the EU side, the EU’s unwillingness to lift the visa requirements for Turkish citizens and to open new chapters in Turkey’s bid for EU membership were the main points of bitterness on the Turkish side. Even though the Joint Action Plan of 2015 had seemed to resolve the migration problem between Turkey and the EU, the European Commission’s 2016 report on Turkey, which brought harsh criticism on Turkey’s new legislation lifting parliamentarians’ immunity from prosecution, independence of the judiciary and freedom of expression,[46] has further worsened the relations. The tension has led to serious diplomatic rifts between Ankara, Greece, Germany and the Netherlands. As Germany and Greece have granted asylum to the coup plotters, the ties between Turkey and the EU have become even further strained.

If only external uncertainties and threats were to be taken into account, Turkey’s deteriorating relations with the West could have resulted in a new Turkish-Russian rapprochement, since Turkey’s threat perceptions and fear of isolation in the Middle East could only be transcended by developing closer relations with Russia. But this time, unlike in the late 1970s, relations between Moscow and Ankara have also relapsed due to their divergent policies in Syria. Starting in the fall of 2011, while Turkey was beginning to actively support regime change in Syria[47], Russia had become Assad’s biggest backer. In the summer of 2013, because of the friction with both the West and Russia, Turkey found itself isolated, a position coined as “precious loneliness” by İbrahim Kalın, the chief foreign policy advisor to the then Prime Minister.[48] With Turkey’s downing of a Russian SU-24 warplane on 24 November 2015, the existing tension between Ankara and Moscow turned into a political crisis which would last until late 2016.

5. Comparative Analysis and Model Application

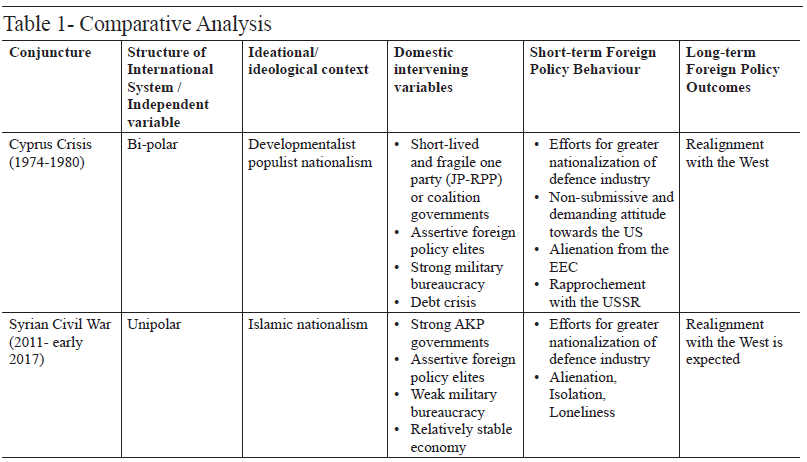

The application of a neo-classical model of foreign policy analysis to the selected crises requires the comparison of the independent variables, ideational contexts, domestic intervening variables, and their impacts on short-term foreign policy behavior as well as the long-term policy outputs. At that point, it is noteworthy to mention that, such a comparison should also extricate the role of domestic intervening variables and systemic incentives since a neo-classical realist model prioritizes the independent variable (the structure of the international system), which is assumed to be the most significant determinant on long term foreign policy outputs.

It is true that the history of relations between Turkey and the West since 1950 is one of ‘abundant drama and posturing’,[49] as the rise and decline of bipolarity has given Turkey numerous opportunities to test and stretch the limits of its place in the Western alliance. Yet, the alienation from the West in the 1970s and since 2016 are quite different from ordinary disputes in terms of scale and scope. In order to understand these exceptional moments of strife, it is vital to analyse the realm of ideology because it constitutes the ideational environment in which political leaders, governments, as well as defence and foreign policy bureaucrats operate. This ideational context shapes the way these actors interpret the international system and Turkey’s relative power in it, which determine the short-term policy outputs. The major common element of the ideological sphere in the 1970s, not only in Turkey but in most of the capitalist periphery, was a populist nationalism, embedded in a developmentalist economic strategy.

The aim of national developmentalism was to promote economic development, which may be accomplished through an import substitute industrialization model and a certain extent of social peace among major economic actors mediated by the state. This strategy required a great deal of populism. All major political actors in Turkey between 1960 and 1980 adopted developmentalism, yet they operationalized it in different ways. Even Demirel, who was the most reliable politician in the eyes of business circles and the US governments throughout the 1960s and 1970s, reflected this ideational environment in his focus on heavy industry.[50]

The Ecevit-led CHP got the rising left-wing anti-imperialist wind behind the idea. Ecevit adopted ‘populism within’, with references to a fair distribution of wealth and to a rich Anatolian civilizational legacy, and ‘nationalism outside’, with an anti-imperialist and pro-independence discourse[51]. The MSP, on the other hand, brought together nationalism, anti-communism, anti-Westernism and the search for justice and development, with a distinct call for a reorganization of state and society through an Islamic ethos. Ecevit and Erbakan, both assertive in foreign policy, were coalition partners during the Cyprus Peace Operation and were later labelled as ‘the conquerors of Cyprus’ by their followers.

It must be noted that the 1970s witnessed the beginning of the erosion of secular elements in nationalism. Not only was a separate Islamist party established for the first time and served as an indispensable partner in all three coalition governments of the decade, but Islamic elements were also increasingly incorporated into the conservative and nationalist traditions in the right-wing through the medium of anti-communism and the idea of Turkish-Islamic synthesis that implied a neo-Ottomanism in foreign policy.[52] The right-wing was first and foremost anti-communist[53] and Washington was regarded as an ally in that framework. Anti-communism was the glue for the ‘Nationalist Front’ coalitions of the AP, MSP and MHP between 1975 and 1977. Nevertheless, although waging a feud against the supposedly Soviet-backed labour movement in Turkey, they welcomed Soviet economic support, and maintained a pro-independent and nationalist position in their relations with the West.

Despite the weak and fragile one-party or coalition governments, there was a continuous and strong foreign and defense policy bureaucracy in the 1970s. Foreign ministry bureaucrats and the military were both homogenous groups trained along secular, nationalist and anticommunist principles to serve for the cardinal aim of survival and continuity of the state. Although there had been some intrusions from the left into both institutions in the 1960s, leftist elements were largely purged; the army’s role and autonomy were expanded through the revised National Security Council and the newly established Supreme Military Administrative Court[54]; and a centralised and systematised secular, nationalist and anti-communist ideology for the army was produced.[55] This army was to reequilibrate Turkey in the Western alliance and largely take over the foreign policy making process in the 1980s.

The ever-mounting debt crisis is the last variable that must be examined to understand both the alienation from and realignment with the West. The structural reasons behind Turkey’s crisis were an overdependence on imported inputs and a relative stagnation in exports. Despite these problems, a considerable injection of foreign sources (credits, foreign aid and immigrant remittances) had made high levels of growth sustainable until 1977, making overdependence on imports and credits a chronic illness. Convertible deposits and other sorts of short-term and high interest rate loans delayed but aggravated the crisis, which broke out in 1977 with severe disruption in foreign trade indicators.[56] New credit channels were conditional upon stability agreements with the IMF, which would be impossible to implement given the strong labour movement and political polarization. When Western sources were unavailable, Turkey turned to the USSR. However, by 1980, the détente was over, and the US was determined to provide no space for its allies but joining the new Cold War as well as implementing neoliberal economic programs.

In the broad ideational context of the 1970s, based on a populist nationalism with an anti-imperialist tone, and under the effect of domestic intervening variables hitherto discussed, certain short-term foreign policy outcomes emerged. Turkey’s immediate response to cope with its isolation in the aftermath of the 1974 Cyprus intervention was the rapprochement with the USSR, and the unilateral annulment of the 1969 Joint Defence Cooperation Agreement that was governing US military operations in Turkish territory, and investments on a national defence industry that would reduce Turkey’s dependency on foreign arms sales. However, none of Turkey’s responses were manifestations of a major re-orientation of Turkish foreign policy. Under Cold War circumstances, a full-scale Turkish-Soviet rapprochement that could transcend the economic cooperation between Ankara and the Kremlin was unsustainable. The Demirel and Ecevit governments, on all occasions, asserted that Turkish-Soviet cooperation had been an economic cooperation and not a political one that could undermine Turkey’s commitments to NATO. Both were well aware that, despite important investments, Turkey’s national defence industry was still far from meeting the demands of the military in a conflict intense environment. Furthermore, no matter how much credits Turkey received from the USSR, it was not comparable to the resources provided by the West. By 1980, the foreign policy elites’ deep-rooted anti-communism, and the takeover of the pro-American military junta regime had transformed the Cold War’s systemic pressures into an expected policy output; Turkey’s re-alignment with the US in the long run.

Contrary to the Cold War’s bipolar structure imposing restraints on the actors’ foreign policy responses, the unipolar post-Cold War system was expected to afford all actors more space to manoeuvre at the regional sub-systemic levels[57]. But unsurprisingly, these different systems are likely to impose realignment with a major power, and almost three decades that have rolled by under the uncertainties of the post-Cold War period have demonstrated that alignment with a major power remains a necessity to survive in the Middle East even for regional powers like Turkey. However, the findings of this research demonstrated that, between 2011 and early 2017, Turkey remained isolated and alienated, and it in fact took at least five years for Ankara to respond to systemic pressures enforcing Turkey to realign itself with at least one of the major powers in the Middle East. In other words, external balancing strategy against the West, which manifested itself through Turkish-Soviet rapprochement, was not a preferred option on the table until mid-2017.

Additionally, similar to the post Cyprus Crisis period’s internal balancing strategy, attempts for a nationalization of the Turkish defence industry gained momentum. According to data reported by SASAD (Savunma ve Havacılık Sanayi İmalatçılar Derneği / Defence and Aerospace Industry Manufacturers Association), the total amount invested in research and development between 2012 and 2016 steadily increased from 772 Million USD to 1.254 Million USD, in which government support to the projects reached a larger share than the private sector’s equity capital ratio.[58]

In the Syrian Civil War case, Russia and Iran appeared as the challengers of US hegemony at the regional level but, unlike in the late 1970s, the belt that would transmit systemic pressures and incentives into the Turkish bureaucracy and foreign policy elites had to operate in an Islamic nationalist context. From 2011 onwards, the AKP’s transformation from pro-Western Islamic liberalism to anti-Western Islamic nationalism not only resulted in an intense Islamization of the country but also penetrated the ideational/ideological context of foreign policy, in which Ankara’s threat perceptions and responses were shaped.

It can be safely argued that religion, and in the Turkish case, Islamic nationalism, is affecting the Turkish leaders’ threat assessments and their perceptions of the world. Islamic nationalism portraying the West as a hostile bloc ‘attempting to corrupt the country’,[59] once championed by the AKP’s predecessor RP (Refah Partisi, Welfare Party) seemed likely to be abandoned by the AKP in its early years.[60] Despite the frictions between Ankara and the West, foreign policy elites had indeed adopted a pro-Western posture for consolidating the party’s power inside and outside. Yet, Islamic nationalism and its framing of the West as an enemy began gaining momentum after 2011. The ending in disappointment of the bid for Turkey’s EU membership, the sectarian pro Muslim Brotherhood ideology and policy formulations towards the Middle East,[61] the emergence of fundamental incompatibilities between Turkey and the West regarding the civil war in Syria, and the AKP’s third electoral victory in the June 2011 general elections, all led to the creation of a new ideological context in which Islamic nationalism began to manifest itself. Expressions and statements such as the ‘Crusaders’,[62] ‘remnants of the Nazis’,[63] ‘coup-plotters’,[64] ‘no one can stop the rise of Islam in Europe’ and ‘Muslim countries must unite and defeat the successors of Lawrence of Arabia,’[65] which began appearing frequently in the speeches of the foreign policy elites demonstrated how the ideational/ideological context had begun to shape Ankara’s foreign policy choices and discursive acts after 2011.

At that point, it is plausible to argue that a consensus between foreign policy elites, bureaucratic structures, and public opinion, was built around the government’s Syria policy and this consensus enabled the foreign policy elites to extract and mobilize the resources essential for the pursuit of foreign policy objectives without any limitations. The civilianization of the National Security Council and the diminishing role of the military in politics between 2007 and 2011 through a series of trials based on ‘fabricated evidence’[66] removed the possible restraints that could have been imposed by the bureaucratic structures on the government’s policy choices. Moreover, consent by the public, whose perceptions are not independent from the domestic ideational/ideological context on the definition of threats, also allowed the government to formulate and implement foreign policy strategies without any further restraints. In a 2017 survey conducted by Kadir Has University’s Center for Turkish Studies,[67] almost 40 per cent of participants described Turkey as an ‘Islamic Country’ and, unsurprisingly, the US ranked first in the threat perceptions of respondents, with 66.5 per cent, a sharp increase compared with the 41.7 per cent in 2013.

This application of the neo-classical realist model to the selected crises in different time intervals reveals the influence of systemic incentives on Turkey’s long-term policy outputs. As the theoretical model puts forward, the completely different ideational/ideological contexts of the Cyprus and Syria crises have produced different short-term responses, but at the end these domestic variables have remained analytically subordinate to systemic incentives. In the first case, Turkey realigned itself with the West to survive in the early 1980s. In the second case, Turkey’s realignment with the West is likely to happen since the country is on the threshold of a serious economic crisis. Even though the recent s-400 missile deal and cooperation in Syria seems like a rapprochement with Russia, Turkey remained isolated at least until the end of 2016. Between 2011 and 2016, Turkey did not make any pragmatic or instrumental moves towards Russia for securing its own strategic interests in Syria, a pattern of short-term behavior that is completely different from Ankara’s efforts to instigate greater cooperation with the USSR during the Cold War.

Last but not least, the neo-classical realist model’s emphasis on the determining role of systemic incentives over long term policy outputs, specifically, realignment with the West, is likely to be validated in both cases. While reconciliation with the US was the hallmark of the military junta regime in the 1980s, the current economic crisis and surrounding threats will likely force Turkey to realign itself with the West. The recent agreement on a plan between Turkey and the US regarding the removal of YPG forces from the Syrian town of Manbij; Erdoğan’s declaration of Britain as an ally, strategic partner and friend during his visit to London in May 2018, and emphasis on the necessity of developing trade relations in the post-Brexit period, can all be taken as the early signs of Ankara’s realignment with the West.

6. Conclusion

The findings of this research demonstrate that Turkey had developed different short-term foreign policy behaviours to similar systemic incentives. In the aftermath of the Cyprus Crisis, Ankara’s immediate responses were rapprochement with Russia, assuming a demanding and non-submissive attitude towards the US, and alienation from the EEC. However, the Syrian Civil War has resulted in a complete alienation and isolation of the country at least up until late 2016. In both cases, the attempts for greater nationalization of the defence industry have been pursued as an internal balancing strategy, whereas rapprochement with Russia to escape the pitfalls of isolation in the Middle East was an external balancing strategy. In this regard, the differences between Ankara’s short-term policy responses can easily be found in the domestic level intervening variables such as the elites and institutions whose threat perceptions have been shaped in completely different ideological contexts. Whereas populist developmental nationalism affected the responses of the foreign policy elites to the emerging crises in the 1970s, Islamic nationalism framing all the foreign powers as enemies has brought Turkey to an impasse. What is common in these different ideological contexts is an historically rooted suspicion towards the West, which has become an intrinsic part of the Turkish political culture.

In an intense environment of Islamization, misperceptions of its own relative power, miscalculation of risks, the hubris feeding Ankara’s lust for the idea that Turkey’s moment had arrived in the new order after the Arab Spring,[68] the diminishing role of the secular bureaucracy, and electoral victories of the ruling party AKP, have all ultimately resulted in the country’s souring relations with nearly all powers in the region. Undoubtedly, the fear of being isolated and alienated in Syria and a souring of ties between Ankara and the West has paved the way to Russian-Turkish rapprochement in the late 2016. After Turkey’s downing of the Russian warplane, such a rapprochement between Ankara and Moscow could hardly be predicted. Yet, continuing frictions with the West, security concerns stemming from the instability in Syria and economic hardships caused by Russian sanctions made it clear that, “Turkey could no longer afford a Cold War with Moscow”.[69]

Different from the actual Cold War’s technical, industrial and financial cooperation, the rapprochement then, has extended to include cooperation against terrorism, and facilitating peace in Syria through creating de-escalation zones. None of these policy outputs, however, has sparked as many concerns in the West as has the S-400 missile deal between Ankara and Moscow. On 29 December 2017 Turkey announced the signing of a deal on Russian supply of S-400 anti-aircraft surface to air missile defense system, which is not compatible with NATO’s radar network. Facing criticisms for the move, Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu denied the comments that Turkey’s axis had shifted from the Euro-Atlantic alliance to Russia[70]. As Çavuşoğlu confirmed, the current rapprochement with Russia cannot be an alternative to Ankara’s partnership with the West, nor is it sustainable. Historically rooted threat perceptions, geo-political rivalries in the Caucasus, Balkans, Transcaucasia, Black Sea and Central Asia, as well as diametrically opposite ideologies of Ankara and Moscow are the major obstacles facing an envisaged trajectory on Turkish-Russian relations that could replace the partnership between Turkey and the West. Therefore, the systemic incentive is likely to result in Turkey’s re-alignment with the West in the long run, as was the case in the 1980s.

Under the spotlight of these findings and recent developments, it can be safely argued that the Western Question in Turkish foreign policy cannot be resolved without addressing the root causes of the problem. Acknowledging the fact that foreign policy decisions are not made in a de-ideological context, anti Westernism, intrinsic to the Turkish political culture, is not a simple conjunctural problem that Ankara can easily overcome, but it can be managed if certain discursive and practical policy adjustments are made. Revising the state of emergency conditions and normalization of the country may lead to the restoration of Turkey’s relations with the West. In relation to that, abandoning the hostile rhetoric that is regularly used to create a grand coalition around the government in the domestic politics can be another option that the foreign policy elites can assume for escaping the vicious cycle in the foreign policy domain. Foreign policy elites’ insistence on framing the West as an enemy may serve for certain practical purposes, such as guaranteeing new electoral victories at home, but it cannot safeguard the country’s national interests in a conflict prone environment. However, as of yet, no earlier signs of normalization have yet been observed on the Turkish side since the uncertainty in Syria still exhibits risks for national security.

Last but not least, even if Turkey adopts a discursive shift and a policy change that can foster a new process of dialogue with its partners in the West, the Western Question in Turkish foreign policy is still likely to remain unsolved since the US and the EU continue to disregard the country’s security concerns. Ankara’s requests for Fethullah Gülen’s extradition have fallen on deaf ears in Washington and the US continues to support the YPG in Northern Syria as a partner in the war against DAESH. Setbacks in Turkey’s long bid for EU membership are also another matter of concern feeding the anti-Western sentiments in Turkish society and among foreign policy elites. As the right-wing parties in growing numbers of EU member states gain electoral victories, the tension between the EU and Turkey is likely to persist.

Despite significant setbacks in the past, Turkey has remained a staunch ally of the West for at least 60 years and even though the Western Question is likely to affect Turkey’s relations with the West in a negative manner, the uncertainties generated by the system itself are manifesting themselves mostly in the regional conflicts such as the Syrian Civil War. Under these circumstances, Turkey’s re-alignment with the West can be anticipated due to the existence of the following factors. First, neither Turkey nor its Western partners have interests in further straining the relations. In an extremely challenging environment where Russia and Iran are militarily engaged in the Syrian Civil War with an aim to expand their spheres of influence, a souring of ties between Turkey and its Western partners can not contain them but instead could easily create much more space for both Moscow and Tehran. Second, Turkey’s fragile economy and unsustainable debt cannot allow Ankara to continue its aggressive posture towards the West. Thus, either voluntarily or involuntarily, common threats perceived by Turkey and its Western partners are expected to impose a rapprochement between the troubled allies.

Altunışık, Meliha B. “The Inflexibility of Turkey’s Policy in Syria.” IEMed Mediterranean Yearbook (2016): 57-62. Accessed February 20, 2018. http://www.iemed.org/observatori/arees-danalisi/arxius-adjunts/anuari/med.2016/IEMed_Med Yearbook_2016_keys_Turkey_Syrias_ Policy_Benli_Altunisik.pdf.

Arango, Tim. “Growing Mistrust Between U.S. and Turkey Is Played Out in Public.” New York Times, December 23, 2013. Accessed February 20, 2018. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/24/world/europe/growing-mistrust-between-us-and-turkey-is-played-out-in-public.html.

———. “Turkish Premier Blames Foreign Envoy for Turmoil.” New York Times, December 22, 2013. Accessed February 20, 2018. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/22/world/middleeast/16-more-arrested-as-corruption-inquir y-in-turkey-widens.html.

Atmaca, Ayşe Ö. “The Geopolitical Origins of Turkish-American Relations: Revisiting the Cold War Years.” All Azimuth 3 (2014): 19-34.

Aydın, Mustafa. “Determinants of Turkish Foreign Policy: Changing Patterns and Conjunctures during the Cold War.” Middle Eastern Studies 36 (2000): 103-39.

Aydın-Düzgit, Senem. “De-Europeanization through Discourse: A Critical Discourse Analysis of AKP’s Election Speeches.” South European Society and Politics 21 (2016): 45-58.

Aydın-Düzgit, Senem and Alper Kaliber. “Encounters with Europe in an Era of Domestic and International Turmoil: Is Turkey De-Europeanizing?” South European Society and Politics 21 (2016): 1-14.

Banchoff, Thomas. “German Identity and European Integration.” European Journal of International Relations 5 (1999): 259-89.

Barkey, Henry J. “Erdoğan’s Foreign Policy is in Ruins.” Foreign Policy, February 4, 2016. Accessed February 20, 2018. http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/02/04/erdogans-foreign-policy-is-in-ruins/

Bayramoğlu, Ali. “Asker ve siyaset.” In Ahmet İnsel and Ali Bayramoğlu, Bir zümre, bir parti, 59-118.

Boll, Michael M. “Turkey between East and West: The Regional Alternative.” The World Today 35 (1979): 360-68.

Bora, Tanıl. Medeniyet kaybı: milliyetçilik ve faşizm üzerine yazılar. İstanbul: İletişim, 2006.

———. “Ordu ve milliyetçilik.” In Ahmet İnsel and Ali Bayramoğlu, Bir zümre, bir parti, 163-78.

———. “Süleyman Demirel.” In Modern Türkiye’de siyasi düşünce, Cilt 9, Dönemler ve zihniyetler, edited by Tanıl Bora and Murat Gültekingil, 502-14. İstanbul: İletişim, 2009.

Bora, Tanıl, and N. Canefe. “Türkiye’de popülist milliyetçilik.” In Modern Türkiye’de siyasi düşünce, Cilt 4, Milliyetçilik, edited by Tanıl Bora and Murat Gültekingil, 635-62. İstanbul: İletişim, 2003.

Boratav, Korkut. Türkiye iktisat tarihi 1908-2002. Ankara: İmge Kitabevi Yayınları, 2003.

Cooper, Orah, and Fogarty, Carol. “Soviet Economic and Military Aid to the Less Developed Countries, 1954-78.”

Soviet and Eastern European Foreign Trade 21 (1985): 54-73.

Criss, Nur B. “A Short History of Anti-Americanism and Terrorism: The Turkish Case.” The Journal of American History 89 (2002): 472-84.

Demirtaş, Birgül. “Turkish Foreign Policy towards the Balkans: A Europeanized Foreign Policy in a De-Europeanized National Context?” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 17 (2015): 123-40.

Devlen, Balkan, and Özgür Özdamar. “Neoclassical Realism and Foreign Policy Analysis.” In Rethinking Realism in International Relations, edited by A. Freyberg-Inan, E. Harrison and P. James, 136-64. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2009.

Doty, Roxanne L. “Foreign Policy as Social Construction: A Post-Positivist Analysis of U.S. Counterinsurgency Policy in the Philippines,” International Studies Quarterly 37 (1993): 297-320.

Dönmez, Yeliz, and Bico, Cem. “Bülent Ecevit.” In Modern Türkiye’de siyasi düşünce, Cilt 4, Milliyetçilik, edited by Tanıl Bora and Murat Gültekingil, 448-53. İstanbul: İletişim, 2003.

Erhan, Çağrı. “ABD ve NATO’yla ilişkiler.” In Türk dış politikası, cilt I, 1919-1980, edited by Baskın Oran, 681-715. İstanbul: İletişim, 2004.

Erhan, Çağrı, and Tuğrul Arat. “AET’yle ilişkiler.” In Türk dış politikası, cilt I, 1919-1980, edited by Baskın Oran, 808-53. İstanbul: İletişim, 2004.

European Commission. “Turkey 2016 Report, SWD 2016 (366) final.” Brussels, November 9, 2016.

Franz, Erhard. “Secularism and Islamism in Turkey.” In The Islamic World and the West: An Introduction to Political Cultures and International Relations, edited by Kai Hafez, 161-75. Leiden: Brill, 2000.

Guan-Fu, Gu. “Soviet Aid to the Third World: An Analysis of Its Strategy.” Soviet Studies 35 (1983): 71-89.

Güner, Serdar. “Religion and Preferences: A Decision- theoretic Explanation of Turkey’s New Foreign Policy.” Foreign Policy Analysis 8 (2012): 217-30.

Güney, Aylin. “An Anatomy of the Transformation of the US–Turkish Alliance: From ‘Cold War’ to ‘War on Iraq’.” Turkish Studies 6 (2005): 341-59.

———. “Anti-Americanism in Turkey: Past and Present.” Middle Eastern Studies 44 (2008): 471-87.

Kadercan, Pelin T., and Burak Kadercan. “Turkish Military as a Political Actor: Its Rise and Fall.” Middle East Policy XXIII (2016): 84-96.

Kadir Has University. “2017 Survey on Turkish Foreign Policy.” Center for Turkish Studies, 2017. Accessed February 20, 2018. http://www.khas.edu.tr/en/news/270.

Kardaş, Şaban. “Türk dış politikasında eksen kayması mı?” Akademik Ortadoğu 5 (2011): 19-42.

Kaygı, Abdullah. Türk düşüncesinde çağdaşlaşma. Ankara: Gündoğan Yayınları, 1992.

Kitchen, Nicholas. “Systemic Pressures and Domestic Ideas: A Neo-classical Realist Model of Grand Strategy Formation.” Review of International Studies 36 (2010): 117-43.

Lobell, Steven E., Norrin M. Ripsman, and Jeffrey W. Taliaferro. Neoclassical Realism, the State and Foreign Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Mankaff, Jeffrey. “Russia and Turkey’s Rapprochement: Don’t Expect an Equal Partnership.” Foreign Affairs, July 20, 2016. Accessed February 20, 2018. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/turkey/2016-07-20/russia-and-turkeys-rapprochement.

Middle East Media Research Institute. “Special Dispatch, No 5962.” February 9, 2015. Accessed February 20, 2018. https://www.memri.org/reports/anti-west-statements-turkish-president-erdogan-and-pm-davutoglu-muslim-countries-must-unite.

Miller, James E. “Telegram from the Department of State to the Embassy in Turkey, June 5, 1964.” In Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XVI, Cyprus; Greece; Turkey. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 2000. Accessed February 15, 2018. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/ frus1964-68v16/d54.

Morgenthau, Hans J. Politics among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948.

Neziroğlu, İrfan, and Tuncer Yılmaz, ed. Hükümetler, programları ve genel kurul görüşmeleri, cilt 5, 26 Mart 1971-17 Kasım 1974. Ankara: TBMM Yayınları, 2013.

Oğuzlu, Tarık. “Middle Easternization of Turkey’s Foreign Policy: Does Turkey Dissociate from the West?” Turkish Studies 9 (2016): 3-20.

Oğuzlu, Tarık, and Mustafa Kibaroğlu. “Is the Westernization Process Losing Pace in Turkey: Who’s to Blame?” Turkish Studies 10 (2009): 577-93.

Oran, Baskın. “Dönemin bilançosu.” In Türk dış politikası, cilt I: 1919-1980, edited by Baskın Oran, 655-80. İstanbul: İletişim, 2004.

Ovalı, Şevket. “From Europeanization to Re-nationalization: Contextual Parameters of Change in Turkish Foreign Policy.” Studia Europea 3 (2012): 17–37.

Öniş, Ziya. “Multiple Faces of the New Turkish Foreign Policy: Underlying Dynamics and a Critique.” Insight Turkey 13 (2011): 47-65.

Rathbun, Brian. “A Rose by Any Other Name: Neoclassical Realism as the Logical and Necessary Extension of Structural Realism.” Security Studies 17 (2008): 294-321.

Ripsman, Norrin M., Jeffrey W. Taliaferro, and Steven E. Lobell. Neoclassical Realist Theory of International Politics. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Rose, Gideon. “Neoclassical Realism and Theories of Foreign Policy.” World Politics 51 (1998): 144-72.

SASAD. “Performance Report.” 2016. Accessed February 20, 2018. http://www.sasad.org.tr/sasad-savunma-ve-havacilik-sanayii-performans-raporu.

Schweller, Randall L. Maxwell’s Demon and the Golden Apple: Global Discord in the New Millennium. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2014.

———. “Neo-classical Realism and State Mobilization: Expansionist Ideology in the Age of Mass Politics.” In Neoclassical Realism, the State and Foreign Policy, edited by Steven E. Lobell, Norrin M. Ripsman and Jeffrey W. Taliaferro, 227-50. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

———. “Unanswered Threats: A Neoclassical Realist Theory of Underbalancing.” International Security 29 (2004): 159-201.

Sezer, Duygu B. “Peaceful Coexistence: Turkey and the near East in Soviet Foreign Policy.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 481 (1985): 117-26.

Snyder, Jack. Myths of Empire: Domestic politics and International Ambition. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1991.

Sözen, Ahmet, and Devrim Şahin. “Perception of Axis Shift in Turkish Foreign Policy: An Analysis through ‘Butterfly Effect’.” İzmir Review of Social Sciences 1 (2013): 47-63.

Stepak, Amir, and Rachel Whitlark. “The Battle over America's Foreign Policy Doctrine.” Survival 54 (2012): 45-66.

Şen, Mustafa. “Transformation of Turkish Islamism and the Rise of Justice and Development Party.” Turkish Studies 11 (2010): 59-84.

Talieferro, Jeffrey W. “State building for Future Wars: Neoclassical Realism and the Resource-Extractive State.” Security Studies 15 (2006): 464-95.

Taliaferro, Jeffrey W., Steven E. Lobell, and Norrin M. Ripsman. “Introduction: Neoclassical Realism, the State, and Foreign Policy.” In Neoclassical Realism, the State and Foreign Policy, edited by S.E. Lobell, N.M. Ripsman and J.W. Taliaferro, 1–42. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Taşpınar, Ömer. “The Anatomy of Anti-Americanism in Turkey.” Brookings Institute, November 16, 2005. Accessed February 15, 2018. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/taspinar20051116.pdf.

Tür, Özlem. “Economic Relations with the Middle East under the AKP: Trade, Business Community and Reintegration with Neighbouring Zones.” Turkish Studies 12 (2011): 589-602.

Wallace, Cissy E.G. “Soviet Economic and Technical Cooperation with Developing Countries: The Turkish Case.” PhD diss., London School of Economics, 1990. Accessed February 15, 2018. http://etheses.lse.ac.uk/1177/1/U048631.pdf.

Weldes, Jutta. “Constructing National Interest.” European Journal of International Relations 2 (1996): 275–318.

Wendt, Alexander. Social Theory of International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Wohlforth, William C. “Realism and the End of the Cold War.” International Security 19 (1995): 91-129.

Yeşilyurt, Nuri. “Explaining Miscalculation and Maladaptation in Turkish Foreign Policy towards the Middle East during Arab Uprisings: A Neoclassical Realist Perspective.” All Azimuth 6 (2017): 65–83.

Yılmaz, Hakan. “Euroscepticism in Turkey: Parties, Elites, and Public Opinion.” South European Society and Politics 16 (2011): 185-208.

Zakaria, Fareed. From Wealth to Power: The Unusual Origins of America’s World Role. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998.