Nathan Andrews

University of Northern British Columbia, Canada

The field of International Relations (IR) has experienced different waves of ‘great debates’ that have often maintained certain theoretical and methodological frameworks and perspectives as core to the field whereas others are seen as peripheral and merely a critique of the former. As a result of this segregation of knowledge, IR has not become as open to dialogue and diversity as we are made to believe. To be sure, aspects of the extant literature speak of IR as being ‘not so international’, a ‘hegemonic discipline’, a ‘colonial household’, and an ‘American social science’, among other derogatory names. Informed by such characterizations that depict a field of study that is not sufficiently diverse, the paper investigates the relationship between pedagogical factors and dialogue in IR. In doing so, it provides preliminary results from a pilot study in February-April 2019 that sought to examine different graduate-level IR syllabi from leading universities in the global North and South (Africa in particular). In particular, the objective was to decipher what course design, including required readings and other pedagogical activities in the classroom, tells us about dialogue and the sort of diversity needed to push IR beyond its conventional canons.

1.Introduction/Background

In light of the persistent dominance of certain types of knowledge, theories and methodologies, there have been repeated calls for better interaction, communication or dialogue in International Relations (IR) scholarship. One of the earliest accounts of the Western dominance of IR is Stanley Hoffman’s article that specifically called IR an ‘American Social Science’.[1] Over the last two decades, scholarship that questions the lack of non-Western or ‘Third World’ perspectives in the theory and practice of IR has bourgeoned. These include contributions from Ole Wæver,[2] Steve Smith[3] and Arlene Tickner[4] among other significant contributions.[5] Overall, the evidence points to an established critique of the status quo in IR.

Much of the contributions noted above have contested the very origins of the field of study. As a distinct field of study, IR is assumed to have been born in 1919 at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth with the foundation of David Davies as the Woodrow Wilson Chair, subsequently followed by chairs established at the London School of Economics and Oxford after Montague Burton.[6] ‘Assumed’ is used here to denote the point that what we know as the origin of IR is what has been transmitted from one generation to the other though it is also known that the origin, nature, scope and purported exceptionalism of IR as told in the story remain ‘foundational myths’.[7] For instance, scholars argue that stories we have heard about 1648 and 1919 are myths that perpetuate the definition of the ontology of Western ‘Self’ as opposed to the ‘Other’.[8] Also, Schmidt has shown that IR was studied long before World War 1 and that idealism was not predominant in the interwar years as the history of IR tells us.[9] Others believe that these mainstream accounts of IR origins present a ‘West Side Story’ that places Western civilization at the centre of history while silencing other forms of knowledge and views about the world.[10] These pieces of evidence point to the fact that none of what we have been taught by our IR professors can be taken as given. What is troubling is the fact that the design and content of current IR course syllabi remain grounded in some of these foundational myths about the field of study as well as the main events and actors that give meaning to some of the core theories of IR.

More problematically with respect to engagement and dialogue with non-Western perspectives, IR, rather than becoming a dynamic field, has become a field rehashing the same old arguments in the same box. How teachers of IR tell the story about the field’s origin (often framed around the logic of ‘great debates’) is, however, usually misrepresented, leading to the assumption that the field has experienced both ontological and epistemological pluralism. Nearly two decades since Smith argued that this purported diversity was far from the truth,[11] the situation is not necessarily better today.[12] This prevalent phenomenon underscored the need for an All Azimuth workshop in 2019 on disciplinary development in IR to examine what organizers characterized as “the persistent core [as opposed to peripheral] exclusiveness in the realm of IR theorizing in particular”[13] despite the emergence of what is believed to be ‘theoretical innovations’ emerging from the global South.[14]

At the same time, it is also necessary to note that IR has not remained an entirely static field. For instance, many course syllabi (some of which are the focus of this contribution) now include weeks devoted to feminist, critical and postmodern theories although the linear manner in which these discussions are proffered in syllabi still give precedence to what comes before as core to the field of study. There is no doubt that interventions from feminist and postmodern scholarship, for example, have added much to our collective understanding of the world. Nevertheless, these important interventions have not necessarily adequately dealt with other equally important issues or even necessarily helped to ensure broader representation. Jackson insists that while constructivism and feminism as part of the neo-positivist agenda for instance can be seen as an effort to incorporate “novel cases and causal factors,” their inclusion in IR theorizing still leaves “the more fundamental philosophical and methodological issues untouched.”[15] As a result, though these efforts do help to expand the box of mainstream IR, they remain firmly situated in Western historicity.

The focus of this contribution is therefore to understand whether the current pedagogical preferences of IR instructors, as seen from their course syllabi content, help to advance dialogue or diversity. I define dialogue as overt openness to alternative ideas, perspectives and worldviews. Diversity is the outcome of such outward openness to ‘the other’. Seeing ‘Western’ as including countries of Europe and North America, I follow the definition of Western IR as “the canon of thought that has developed around UK and particularly US practices of the IR discipline.”[16] Western scholarship, which is described as a ‘world of thinking’ as opposed to the geographical location of such scholarship, is also regarded as “scholarship that perpetuates Eurocentrism in the sense that it celebrates theories, methods and research practices popularised in a particular area of the world without due regard to the diversity of perspectives existing elsewhere.”[17]

The purpose of this paper, therefore, is to examine the extent to which the predominance of Western IR in graduate-level course syllabi hinders the dialogue and diversity that need to be maintained in IR. In line with this objective, the next section of the paper examines the concepts of dialogue and diversity in order to briefly frame the ways in which they have been explored in the scholarship. This is followed by a discussion of the methodology used to collect the preliminary data that informs the subsequent analysis of graduate-level IR course syllabi in some leading universities in the world, which entails the bulk of the paper. The conclusion reflects on some strategies that can be used to address the identified lack of dialogue or diversity in IR scholarship.

2. Debating Dialogue & Diversity in IR

Dialogue and diversity have been some of the buzzwords in IR. In fact, the debates around these notions are often impassioned particularly due to the understanding that much of the world outside of core countries in the West are marginalized in IR.[18] As a result, it is believed that through “dialogue within as well as between cultures and locations, East, West, North, South” IR can become a truly ‘universal’ or ‘global’ field of study that best engages with alternative perspectives that facilitate a fuller understanding of the world.[19] By so doing, IR could (re)discover its sense of purpose and meaning for all of its audiences. This expectation underlies the idea of pluralism, which is “a core premise upon which ‘non-Western’, ‘post-Western’, and ‘Global’ IR projects are all founded.”[20] A recent contribution has broken down the concept of dialogue to explore its essence in IR, considering the fact that dialogue in itself can be scripted or staged – in which case it fails to reveal the essence of a true two-way communication.[21] According to Eun, dialogue can be seen as an “intersubjective practice of deliberation,” which is quintessential to the ideas from which the notion of deliberative democracy has gained meaning.[22]

As used in IR, dialogue entails multiple routes of communication among diverse perspectives although this is usually characterized as a two-way (or binary) interaction between Western and non-Western IR or between the core and periphery. The act of reconciling these hitherto disparate perspectives is to ensure diversity and recognize multiple kinds of knowledge and the centres of knowledge production. As such, Eun believes that for a meaningful dialogue to be had in IR, “a broad definition of what counts as scientific methodology for international studies must first be achieved.[23] In other words, dialogue cannot begin unless equal scientific validity is granted to diverse approaches to the study of IR.” The idea of ‘equal scientific validity’ here implies that the actors involved in the dialogue should be treated equally and their knowledge or contribution to the said dialogue should be treated as equally valid. In essence, dialogue in IR entails talking and listening to each other instead of talking at, talking over or blatantly refusing to recognize ‘the other’. Yet despite how reasonable this description of dialogue in IR sounds, we can for now think of it as merely an idealistic vision because it does not adequately capture what happens in practice.

In a previous contribution elsewhere to discussions around the lack of diversity or absence of non-Western perspectives in IR, a colleague and I highlight four interrelated reasons why alternative worldviews could make a difference: First, it will make the field of study become properly qualified as ‘international’. Second, it de-centres the status quo by shifting the field from the myopia of dominant perspectives. Third, alternative worldviews lead the field towards ‘pluri-versality’ rather than universality. Fourth, it reveals the potential of imagining a ‘post-racist’ field of study resulting from “a decolonisation of the subject matter, management of knowledge and of concepts and methods, and academic independence or, potentially, interdependence.”[24] To many writers, the imperial heritage of IR informs why the notion of dialogue has become merely a buzzword instead of facilitating diversity by centering marginalized voices and interpretations.[25] Permit me to quote at length an interesting excerpt from Aydinli and Mathews, which further underscores the persistent lack of dialogue between core and periphery IR scholars:

The four arguably leading IR journals, which set the cutting-edge agenda for the discipline, International Organization, International Security, International Studies Quarterly, and World Politics, have an average of less than 3% of their contributors coming from the periphery, and less than 12% coming from outside the United States. This result ultimately reveals to us the best picture of how infrequently not only the traditional periphery but all scholars outside of the United States are being recognized. Perhaps most ironic is the case of the International Studies Quarterly. As the flagship journal of the ISA, an association whose very constitution dictates that it promotes inter-group dialogue [emphasis mine], less than 10% of its contributors over the past decade have come from outside of the United States, and less than 1½% have come from the periphery.[26]

The observations above are no doubt somewhat dated but the situation is not necessarily better today, as noted above.[27] An important question worth asking is this: If dialogue is not occurring effectively, why is that the case and, in other words, what are the structural problems within core-periphery disciplinary relations that limit such dialogue? For this question, it is important to briefly reflect on both epistemic imperialism and academic dependency as perspectives that provide a nuanced understanding of the persistence of some key issues that underscore the imbalance in the production and consumption of IR knowledge. Along the lines of cultural imperialism, epistemic imperialism explains the tendency to privilege one’s ways of knowing or theorizing over others based on the perception of one’s own superiority.[28] Alatas characterizes academic dependency as “a condition in which the social sciences of certain countries are conditioned by the development and growth of the social sciences of other countries to which the former is subjected.”[29] These two concepts are co-constitutive in the sense that they both explicitly point to imperialism or neo-colonialism (and ultimately Western-centrism or Eurocentrism) as a key driver of the core-periphery divide in IR in particular and the social sciences in general.[30] In essence, “the structural inequality that dependency theorists refer to has translated into epistemic inequality – a case where some ‘knowers’ have more recognition and privileges than others, often racialised ‘others’.”[31]

In other words, the context of the unequal power structures that govern the global capitalist economy underlie how the ‘big powers’ in economic and social terms also tend to be the ‘big powers’ in the social sciences, a phenomenon which further perpetuates the epistemic authority and dominance of certain privileged voices and ‘knowledge holders’ in leading countries.[32] This also explains the persistence of the apparent exclusiveness of core (as opposed to peripheral) actors and perspectives in IR theorizing. Within the context of this paper, dialogue and diversity are used interchangeably. Despite what may be considered as analytical differences, these concepts both illuminate the essence of purposive communication and cross-pollination that will ensure that IR addresses the “representational deficiency”[33] that has been described in this paper thus far.

3. Methodology

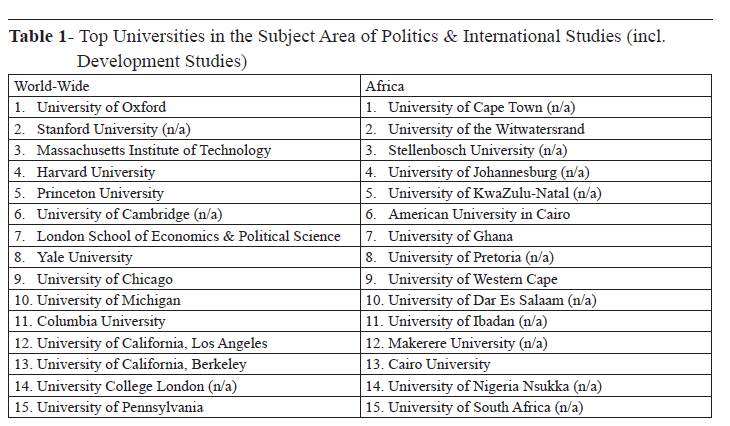

The methodology for this study followed three stages. Stage one entailed a search for leading (mostly ‘top’ 25) IR departments in the world using the 2019 Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings. Since many non-Western IR departments did not immediately feature in the ranking of top IR departments in the world (see Table 1), the search was subsequently refined to specifically look for top African universities with an IR department or school. However, this was not straightforward either as the continent appeared fragmented into either the Arab Region, Emerging Economies or South Africa as part of the BRICS. Ultimately, a search performed on February 28, 2019 for the top world-wide and African universities by the subject area of ‘Politics & International studies” (under the social sciences category) produced 666 total entries, of which only 15 African countries appeared. This number was therefore categorized as the ‘top 15’ IR departments in Africa based on their respective positions in the retrieved list of global universities.

The second stage involved retrieving core graduate-level IR course syllabi from the 30 universities listed above. This process entailed visiting the websites of respective departments of politics and IR, retrieving course syllabi that were already available online or emailing instructors. As this was intended to be a preliminary survey of what is out there in existing syllabi, I relied on information that was readily available online but in the case of Africa I had to email instructors as almost nothing was posted online. Thus, “n/a” in Table 1 means that course syllabi were not available because no core IR course is taught at the graduate level, the syllabi were not available online and email solicitations to instructors did not yield positive results or the program website was not functioning at the time of the search. Overall, the syllabi retrieved covered core IR courses taught over the period of 2014 and 2019.

Once the syllabi were retrieved, stage three of the methodology entailed an analysis of the syllabi content to explore what they contain, what they exclude and whether the pedagogical preferences of the instructors help to advance dialogue or diversity in IR.[34] For instance, the analysis entailed counting how many times a particular article/book/author is used in all syllabi and how the various weeks are designed to incorporate alterative theories beyond the usual suspects such as realism, liberalism, the English School and constructivism. This analysis was meant to examine whether equal amount of space was given to Western and non-Western perspectives – something that was deciphered from the titles and authorships of the weekly readings assigned in respective syllabi.

The diversity of outcome, or lack thereof, resulting from this search is notable. The world-wide rankings are dominated by universities located in the U.K. and U.S. – meaning that the leading universities in the world are found in the rich and industrialized countries. Times Higher Education evaluates institutions through five performance indicators, namely teaching, research, citations, international outlook and industry income.[35] High-ranking institutions possess substantial tuition rates, leading to higher incomes, better facilities, and increased research productivity (i.e. number of publications and citations). Likewise, institutions located in industrialized nations have greater access to public funding for research, a factor dependent upon national policy and economic circumstance.[36] These universities can also attract funding from the commercial marketplace.

Together, the factors noted above provide hints to the relative inequality between ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ nations in terms of the quality of higher education.[37] In this context, however, South African universities stand out as leaders in knowledge production and consumption due to what Bond[38] has characterized as ‘South African sub-imperialism’, which is informed by the neoliberal stance the South African government adopted in the post-apartheid era, with national elites collaborating with Western financial powers to facilitate the entry of transnational capital into the country. Overall, the THE Rankings tend to reproduce inequality not only between the ‘rest of the world’ and Africa, but also among universities in Africa. The preliminary analysis offered here reveals a systemic poverty of diversity in rankings of higher education institutions on the African continent. To what extent this structural issue impacts the content of IR syllabi at the graduate level is an open-ended and perhaps unanswerable question in this particular paper.

4. Findings: What’s in a Course Syllabus?

Out of the 12 Western Universities listed above from which syllabi were retrieved, seven offered a core IR course at the PhD level and five at the Master of Arts (MA), Master of Science (MSc) or Master of Philosophy (MPhil) levels for degrees in Political Science and/or International Relations. Oxford University and the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) were the only two universities to offer a full year-length IR course. The course names vary minimally between “Theories of IR,” “IR Theory” or simply “Seminar on/in IR,” except for the University of Oxford which offers “The Development of the International System and Contemporary Debates in IR Theory” and the University of Michigan which offers a “Proseminar on World Politics.” Stanford University and University College London both offer graduate-level courses in IR though their syllabi were not included in this study. The University of Cambridge does not offer a core IR seminar course for its MPhil in International Relations and Politics; instead, students are offered a free choice from a list of related courses. Cambridge represents an anomaly in this regard, as the other universities mandate that graduate students take a core or compulsory course in IR theory.

Out of the 15 African Universities listed in Table 1, I was able to retrieve five syllabi from the University of Witwatersrand, American University in Cairo, University of Ghana, University of Western Cape and Cairo University – representing south, west and north Africa. The course titles were along the lines of either “Theories of IR” or “Advanced Studies in IR.” The University of Nigeria Nsukka does not offer graduate-level programs in Political Science and/or International Studies. Both Stellenbosch University and University of South Africa do not offer IR courses for their graduate degrees in Political Science and/or International Politics/Studies, but an array of other courses are available. In the case of the University of Johannesburg, graduate students participate in research by dissertation only, and therefore there is no graduate IR seminar course. The University of Cape Town, the University of KwaZulu-Natal, the University of Western Cape and Makerere University, while offering graduate-level courses in IR, did not have syllabi available online nor were email solicitations to department heads or course instructors successful in obtaining relevant syllabi.

Furthermore, the University of Pretoria offers master’s degrees in Diplomatic and Security Studies, but there is no information online as to the courses offered at the graduate level and email solicitations to the coordinator of the program were unsuccessful. Similarly, the University of Dar es Salaam, while providing undergraduate courses in IR and an MA in IR, did not have information online about postgraduate courses and emails to the department head remained unanswered. The webpage of the College of Social Sciences for postgraduate programs had also not been updated since the 2015/2016 academic year. In this regard, part of the challenge in retrieving syllabi from African universities is that some websites were no longer functional at the time searches were performed in March 2019 or there was little to no information on the graduate programs offered. In another example, the website for the Department of Political Science at the University of Ibadan was not working at the time of searching in March 2019 and email solicitations were unsuccessful in retrieving syllabi.

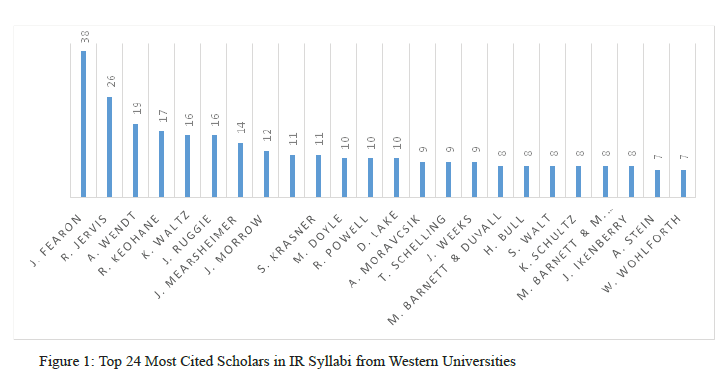

Most syllabi from Western universities trace the theoretical progression and methodological development of IR in a linear fashion, focusing on realism, neorealism, classical liberalism, liberal institutionalism, constructivism and the English School. There are slight variations among syllabi in terms of curriculum design, including Harvard University,[39] which groups theories between material, social, rationalist and psychological approaches to IR, and the University of Michigan which groups research into areas of interest.[40] The common goals shared between syllabi include: (1) understanding the structure of the international system and explaining state behaviour, (2) grasping the casual mechanisms associated with various political phenomena, and (3) evaluating the empirical implications of various theoretical approaches. The classical texts of IR’s major traditions dominate all Western syllabi, particularly the realist, liberalist and constructivist writings of the authors listed in Figure 1.

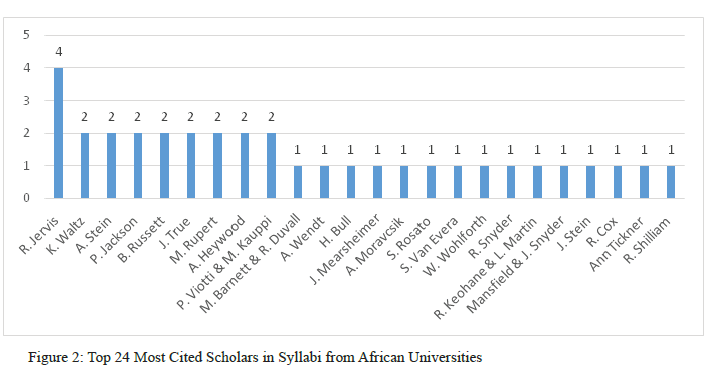

In analyzing the retrieved syllabi, I chose to count the number of times various authors appeared rather than singular texts, as I believe the former approach can give us a better idea of representation in terms of whose voice and expertise counts in the field of IR. In the data collection phase, I accounted for the required or mandatory readings to the exclusion of supplementary or recommend readings for each course.[41] Figure 1 reveals that the traditions of realism, liberalism and constructivism remain at the core of Western IR curricula, with American and European men cited most often. Nine out of twelve syllabi focus solely on Western approaches to IR and Euro-centric debates within the field. Critical and non-Western perspectives are given little to no space in Western IR syllabi, except the University of Oxford and LSE which dedicate multiple weeks to non-conventional theories, as well as Harvard University which reserves one week for the topic of gender and race and particularly include Vitalis[42] in the introductory week. Interestingly, when one collates the data on assigned readings in the syllabi of African universities, European and American theorists still dominate the curriculum (as can be seen in Figure 2).

The postgraduate IR seminar taught at the University of Ghana shares some similarities with those of Western universities in that the “course does not sacrifice the classical theories that continue to give the field its heartbeat.”[43] This is in a way reflected in the predominance of mainstream theorists in the list of 24 most cited scholars, as shown in Figure 2. Unlike the syllabi of most Western universities, however, “sufficient space is given to emerging theories that demonstrate that the field of International Relations, just like any dynamic field in the social sciences, is theoretically abreast with the challenges of change in the global system.” Like the University of Ghana, the course at the University of Western Cape emphasizes the importance of understanding IR’s traditional theories and concepts but takes a more critical approach by asking “why does theory matter? Which world views are held about theory?”[44] These questions at the very least open up avenues for students to not take established theoretical perspectives as given.

It was not possible to compare the frequency of authors in Western vs. African syllabi due to methodological limitations, namely the fact that only four African IR syllabi were surveyed compared to 12 from Western universities.[45] Any quantitative analysis or info-graphic would skew the results due to this numeric discrepancy. Thus, a qualitative approach is more appropriate in this context to reflect on general trends. One interesting finding was that while scholars of the global South are placed at the periphery of IR’s Western core in the syllabi of European and American universities, instructors at African universities are more likely to incorporate contributions by non-traditional or critical scholars in their syllabi, thereby helping to advance dialogue and diversity in IR. Three out of four[46] of the collected syllabi from African universities devote an equal amount of time to conventional and critical theories, including Marxism, postcolonialism, feminism and poststructuralism. This finding further suggests that more dialogue is being encouraged by scholars of the global South than is the case in the global North.

5. Does IR Course Design Matter for Dialogue and Diversity?

To sum up the key findings of this paper, excluded from nearly all Western IR syllabi examined are feminist, Marxist, postcolonial, structural and ‘non-Western’ approaches to the study of IR. Most Western graduate-level IR syllabi continue to focus on Euro-centric scholarship, with critical contributions to the field sitting at the margin, save the University of Oxford, LSE and Harvard University which make a conscious effort to include ‘subaltern’ voices in the study of IR. Essentially, these three universities are the only ones among their Western counterparts that overtly engage with IR’s imperialist origins, with the goal of exposing students to alternative approaches. This is done by listing readings by theorists such as Robert Cox, Robbie Shilliam, Amitav Acharya, Immanuel Wallerstein, Ann Tickner, Laura Sjoberg and Arlene Tickner. The point, however, is that most of these scholars were not among the most cited across the 16 course syllabi in both Western and African universities – with many of them receiving only one or two counts across the respective syllabi examined.

The findings suggest that there is limited openness to alternative ideas, perspectives and worldviews in the IR courses of Western universities. While some instructors are upfront in recognizing the limitations of the field in terms of its Euro-centric roots, few put diversity into practice through their pedagogical preferences. At least as can be deduced from the design of core IR courses, ‘marginal perspectives’ remain at the periphery of these syllabi. If IR is to become ‘truly global’ in scope,[47] IR instructors need to go beyond the Western canon towards critical understandings of the international order and of modernity itself. As Shilliam writes, they must “engage with non-Western thought in ways that refuse to render it exotic to, superfluous to or derivative of the orthodox Western canon of social and political thought.”[48] This means that designing core IR courses such that the “course does not sacrifice the classical theories that continue to give the field its heartbeat,” as described in the University of Ghana syllabus,[49] is not necessarily a useful direction toward moving the field beyond its orthodox canons even if the same syllabus includes certain non-Western perspectives.

The hegemony of American and European theorists leads to African institutions adopting their writings in the IR syllabi, further resulting in a dearth of non-Western perspectives. Using the 2014 TRIP survey, Wemheuer-Vogelaar and colleagues investigate claims that there is “a division of labor within IR wherein scholars in the West are responsible for theory production while the non-West supplies data and local expertise for theory testing.”[50] They find that non-Western scholars do not value IR scholarship from the global South significantly more than Western scholars, which is consistent with the findings in this paper. Perhaps this so-called ‘division of labour’ explains why some of the 15 African universities sampled (e.g. University of Nigeria Nsukka, Stellenbosch University, University of South Africa and University of Johannesburg) do not have an existing graduate-level course on IR theory. It can also explain why the postgraduate IR course offered at the University of Witwatersrand focuses primarily on applied theory and qualitative/quantitative methods used to conduct research in IR as a way of preparing students for their empirical research projects.[51] Yet these notions around a purported division of labour between Western and non-Western IR scholars, which are informed by epistemic imperialism, augment the North-South divide in IR and leads to the dependency on knowledge (i.e. theories and perspectives) propounded in the West.[52] What this means is that accounts of Western scholars are deemed to be theoretically significant to the field while contributions by non-Western scholars maintain the stereotypical categorization as ‘area’ or ‘development’ studies.

The findings in this paper underlie the argument that dialogue and diversity are two things that are still lacking in IR course syllabi. Theories from the non-West remain unrecognized within and outside IR’s Western core. Likewise, critical theories are treated as an afterthought – a mere critique of historically dominant narratives. This means the sort of dialogue or pluralism that scholars have postulated[53] is far-fetched. Yet, the opposite seems true for non-Western scholars (at least the professors teaching the IR courses in African universities examined here). Although Western scholarship tends to be central to most of the syllabi, students are exposed to alternative perspectives that critique aforementioned Western theories. In a way, this trend is more progressive towards the dialogue needed to move IR beyond its orthodox canons.

Apart from the general lack of representation in the top-cited scholars across syllabi, a question worth examining is whether mainstream IR remains a white man’s club. From both Figures 1 and 2, the answer to this question appears to be a straightforward ‘yes’. The results, thus, augment research that has shown a prevalent gender citation gap in IR which explains the dominance of male-authored readings assigned in syllabi.[54] As seen in Figure 1, only Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink have been able to significantly penetrate the male-dominated list of top-cited scholars across the syllabi examined here. The same old white men who were involved in the ‘great debates’ many decades ago remain the ones students of the 21st century are reading with the same old texts that are often twice or even thrice as old as the students reading them. This point is not to suggest that the ‘classics’ are not important. In fact, every discipline needs these seminal texts as a way of ‘disciplining’ students on the contours of an established field of study. The argument, however, is the fact that overemphasizing the significance of the classics hinder purposive dialogue with alternative (‘other’) perspectives. Especially considering research evidence that questions the very premise upon which some IR classics were founded,[55] these texts that are central to mainstream IR are not necessarily sacrosanct. Additionally, their prominence in IR syllabi is also surprising considering the growing scholarship that examines IR theorizing and other innovations ‘from elsewhere’.[56] Overt openness to some of these perspectives and worldviews will, therefore, require IR syllabi to move beyond the current characterization of mainstream IR as a white man’s club.

6. Conclusion

It is worthy of note that focusing on graduate-level course syllabi alone does not present us with a complete picture of how well IR is doing with regard to dialogue and diversity. For instance, the paper does not sufficiently account for the structural and logistical constraints that tend to undermine IR instructors’ efforts to frequently revise their syllabi in light of the need for broader engagement. Nonetheless, course syllabi still serve as a starting point in mapping what we teach and learn in the classroom and how that informs the ‘international’ nature of IR – and that is precisely why this paper has chosen to engage with the field from that standpoint.

The discussion in this paper shows that despite increased awareness of the issue of and need for dialogue and diversity, there is still a largely accepted continuation of the dominance of the core in IR. The awareness is evidenced in syllabi that have no doubt made efforts to include theories and theorists beyond the usual suspects along the lines of realism, liberalism and constructivism. In some instances, instructors provide a background that contextualizes the knowledge that students are going to be exposed to in a manner that seeks to critique what is dominant. Yet, the findings also show that there is the need for more purposive engagement with critical non-Western scholarship. What does it mean to think critically about IR? How can we constructively imagine and identify new questions, worldviews and methodological approaches that can help move the field forward if we are not open to dialogue and diversity? This paper represents a starting point for thinking beyond IR’s current philosophical, theoretical, empirical as well as pedagogical limitations.

One can concur with Eun who argues that “rather than unquestioningly applying Western-centric IR theories or developing non-Western indigenous knowledge to replace those theories, we need to focus on promoting dialogue between them, with the aim of creating complementary understandings of our complex world.”[57] But the fact is that this intersubjective understanding of the complex world IR scholarship attempts to explain is not evidenced in either IR practice and pedagogy. In particular, the continued peripheralization of critical theories and scholars in Western syllabi problematizes the global relevancy of IR theory and reveals a persistent lack of diversity in the field of study. Increased dialogue between Western and non-Western scholars is needed to push IR beyond its Euro-centric understandings of the world. For instance, incorporating African experiences and African scholarship into the IR syllabi could help open the field to new areas of inquiry.[58] Yet, it is troubling to see in the few syllabi examined that African IR professors still have work to do in incorporating such insights into the design of their core IR courses.

In conclusion, the findings in this paper point to a closure of the field to ‘other’ voices and worldviews. The representation that is needed to enhance dialogue should not be thought of as merely geography-bound since there are many IR scholars in multiple sites (i.e. both core and periphery institutions) who are the helm of the fight for diversity. In addition to being wary of how we continue to define what constitutes the canons of IR, the way forward will entail the need for IR professors to include more non-mainstream readings in their course syllabi in order to curtail the citational privilege core Western theorists have gained in the existing scholarship. This will ensure that the future generation of IR spearheads (or prodigies of IR scholarship) are exposed to alternative worldviews, approaches and methodologies that could open up the field to informed dialogue.

Acharya, Amitav. “Dialogue and Discovery: In Search of International Relations Theories Beyond the West.” Millennium 39, no. 3 (2011): 619–37.

–––. “Global International Relations (IR) and Regional Worlds: A New Agenda for

International Studies.” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 4 (2014): 647–59.

Ake, Claude. Social Science As Imperialism: The Theory of Political Development. Ibadan:

Ibadan University Press, 1979.

Alatas, Syed Farid. “Academic Dependency and the Global Division of Labour in Social

Science.” Current Sociology 51, no. 6 (November 2003): 599–613

–––. “Academic Dependency in Social Sciences: Reflections on India and

Malaysia.” American Studies International 38, no. 2 (2000): 80–96.

Amsler, Sarah S., and Chris Bolsmann. “University Ranking as Social Exclusion.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 33, no. 2 (2012): 283–301.

Andrews, Nathan, and Eyene Okpanachi. “Trends of Epistemic Oppression and Academic

Dependency in Africa’s Development: The need for a new intellectual path.” Journal of

Pan African Studies 5, no. 8 (2012): 85–104.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Gonca Biltekin, eds. Widening the World of International Relations:

Homegrown Theorizing. Routledge, 2018.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Julie Mathews. “Are the Core and Periphery Irreconcilable? The Curious

World of Publishing in Contemporary International Relations.” International Studies

Perspectives 1, no. 3 (2000): 289–303.

Bilgin, Pinar. “Thinking Past ‘Western’ IR?.” Third World Quarterly 29, no. 1 (2008): 5–23.

Bond, Patrick. “The ANC’s ‘Left Turn’ & South African Sub-imperialism.” Review of African

Political Economy 31, no. 102 (2004): 599–616.

Brown, Chris. “The Future of the Discipline?” International Relations 21, no. 3 (2007): 347–50.

Colgan, Jeff. “Gender Bias in International Relations Graduate Education? New Evidence from

Syllabi.” PS: Political Science & Politics 50, no. 2 (2017): 456–60.

Compaoré, WR Nadège. “Rise of the (Other) Rest? Exploring Small State Agency and

Collective Power in International Relations.” International Studies Review 20, no. 2

(2018): 264–71.

De Carvalho, Benjamin, Halvard Leira, and John M. Hobson. “The Big Bangs of IR: The Myths

that Your Teachers Still Tell You about 1648 and 1919.” Millennium 39, no. 3 (2011): 735–58.

Eun, Yong-Soo. “Beyond ‘the West/non-West Divide’ in IR: How to Ensure Dialogue as Mutual

Learning.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 11, no. 4 (2018): 435–49.

–––. “Opening up the Debate Over ‘Non-Western’ International Relations.” Politics 39, no. 1 (2019): 4–17.

Harvard University. “Government 2710: Field Seminar on International Relations.”

2018. Copy of document in author’s possession.

Hobson, John M. “Is Critical Theory Always for the White West and for Western Imperialism?

Beyond Westphilian towards a Post-Racist Critical IR.” Review of International Studies 33, no. S1 (2007): 91–116.

Hoffman, Stanley. “An American Social Science: International Relations.” Daedalus 106, no. 3

(1977): 41–60.

Inayatullah, Naeem, and David L. Blaney. International Relations and the Problem of Difference. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Jackson, Patrick Thaddeus. The Conduct of Inquiry in International Relations: Philosophy of

Science and its Implications for the Study of World Politics. London and New York:

Routledge, 2011.

Jordan, Richard, Daniel Maliniak, Amy Oakes, Susan Peterson, and Michael J. Tierney. “One

Discipline or Many? Survey of International Relations Faculty in Ten Countries.”

Teaching, Research and International Policy (TRIP) Project. Williamsburg, VA: Institute

for the Theory and Practice of International Relations, 2009.

Kim, Hun Joon. “Will IR theory with Chinese characteristics be a powerful alternative?” The

Chinese Journal of International Politics 9, no. 1 (2016): 59–79.

Leeds, Brett Ashley, J. Ann Tickner, Colin Wight, and De Alba-Ulloa. “Power and Rules in the

Profession of International Studies.” International Studies Review 21, no. 2 (2019): 188–209.

Levine, Daniel J., and David M. McCourt. “Why does Pluralism Matter When We Study Politics? A View From Contemporary International Relations.” Perspectives on Politics 16, no. 1

(2018): 92–109.

Maliniak, Daniel, Ryan Powers, and Barbara F. Walter. “The Gender Citation Gap In International Relations.” International Organization 67, no. 4 (2013): 889–922.

Maliniak, Daniel, Susan Peterson, Ryan Powers and Michael J. Tierney. TRIP 2014 Faculty

Survey. Williamsburg, VA: Institute for the Theory and Practice of International Relations,

2014.

Mitchell, Sara McLaughlin, Samantha Lange, and Holly Brus. “Gendered Citation Patterns in

International Relations Journals.” International Studies Perspectives 14, no. 4 (2013): 485–92.

Odoom, Isaac, and Nathan Andrews. “What/Who is Still Missing in International Relations

Scholarship? Situating Africa as an Agent in IR Theorising.” Third World Quarterly 38,no.

1 (2017): 42–60.

Schmidt, Brian C. “Anarchy, World Politics and the Birth of a Discipline: American International Relations, Pluralist Theory and the Myth of Interwar Idealism.” International Relations 16, no. 1 (2002): 9–31.

–––. “Lessons from the Past: Reassessing the Interwar Disciplinary History of

International Relations.” International Studies Quarterly 42, no. 3 (1998): 433–59.

Shilliam, Robbie, ed. International Relations and Non-Western Thought: Imperialism,

Colonialism and Investigations of Global Modernity. London: Routledge, 2011.

Smith, Karen. “Has Africa got Anything to Say? African Contributions to the Theoretical

Development of International Relations.” The Round Table 98, no. 402 (2009): 269–84.

–––. “Reshaping International Relations: Theoretical Innovations from Africa.” All

Azimuth 7, no. 2 (2018): 81–92.

Smith, Steve. “The Discipline of International Relations: Still an American Social Science?” The

British Journal of Politics & International Relations 2, no. 3 (2000): 374–402.

Teschke, Benno. The Myth of 1648: Class, Geopolitics and the Making of Modern International

Relations. London: Verso, 2009.

THE Rankings. “World University Rankings 2019: Methodology.” Accessed February 28, 2019. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/methodology-world-university-rankings-2019.

Tickner, Arlene B. “Latin American IR and the Primacy of lo práctico 1.” International Studies

Review 10, no. 4 (2008): 735–48.

–––. “Seeing IR Differently: Notes from the Third World.” Millennium 32, no. 2

(2003): 295–324.

University of Ghana. “POLI626: Theories of International Relations.” 2014. Copy of document in author’s possession.

University of Michigan. “Political Science 660: Proseminar on World Politics.” 2018. Copy of document in author’s possession.

University of the Western Cape. “POL 730/840: International Relations Theory.” 2018. Copy of document in author’s possession.

University of Witwatersrand. “INTR4018: International Relations Applied Theory and Research

Methods.” 2019. Copy of document in author’s possession.

Vitalis, Robert. White World Order, Black Power Politics: The Birth of American International

Relations. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015.

Wæver, Ole. “The Sociology of a not so International Discipline: American and European

Developments in International Relations.” International Organization 52, no. 4 (1998):

687–727.

Wemheuer-Vogelaar, Wiebke, Nicholas J. Bell, Mariana Navarrete Morales, and Michael J.

Tierney. “The IR of the beholder: Examining global IR using the 2014 TRIP

Survey.” International Studies Review 18, no. 1 (2016): 16–32.

Yew, L. The Disjunctive Empire of International Relations. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003.