İsmail Erkam Sula

Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University

Buğra Sarı

Mersin University

Çağla Lüleci-Sula

TED University

International Relations (IR) in Turkey has been assessed by scholars on topics, including but not limited to the need to increase contributions from Turkish IR scholars to theoretical discussions, the need for homegrown theorizing, and to improve the methodological quality of IR research originating in Turkey. This literature has revolved around the diagnosis of and prescriptions for what is referred to as the ‘disciplinary underachievement’ of IR in Turkey. Recently, an increasing number of scholars have focused on disciplinary self-reflection discussing the limitations and prospects in the state of the IR discipline in Turkey. Adding to this emergent literature, this paper identifies the reasons for the ‘disciplinary underachievement’ in Turkish IR. The paper discusses the conditions that hamper IR education in Turkey under three groups: 1) the structure and content of undergraduate and graduate curricula, 2) the state of IR as an academic discipline in Turkey, and 3) the state of IR literature in Turkish. The paper also offers suggestions for a prospective treatment to improve the state of the IR discipline and pedagogy in Turkey. It argues that an improvement in the quality of IR education has significant potential to contribute to further inclusion of locally produced IR knowledge into ‘global IR,’ which is widely cited in the existing literature as a significant sign of ‘disciplinary progress.’

Most IR scholars in Turkey are familiar with ‘self-reflections’ on the state of the discipline. Since the early 2000s, the literature has been built up on the development and limitations of the IR discipline and pedagogy. Discussions vary around topics ranging from structural conditions, such as the limitations of the higher education system, to the content-based and quality-based factors, such as critiques on theoretical and methodological improvement. In this article, we aim to identify what has been discussed so far, compare those discussions with what we observe and experience in the field, and point at a potential direction for further treatment of the existing limitations. We argue that reasons for what is cited as the ‘disciplinary underachievement’ of Turkish IR in the literature mainly emanate from pedagogical limitations at both undergraduate-level and graduate-level education.

Before diving into the literature and presenting our analysis and contribution, we consider it necessary to locate ourselves in this study as researchers who have experience in research abroad but got all our degrees in schools/universities in Turkey and currently hold faculty positions at different universities in the country. As scholars who have experienced most of the disciplinary limitations firsthand, we think that IR academia in the country has matured enough to move forward from ‘diagnosis and prescription’ of limitations to the ‘treatment’ of them. We argue that searching for treatment is significant because the persistence of those limitations continues to affect us and many of our counterparts on at least two main aspects: the training we offer in our IR classes and the way we do research and/or determine the agenda that we work on. We base our arguments and analyses on the assumption that educational background has a direct impact on what scholars research, and maybe more importantly, the ways scholars produce disciplinary knowledge.

The article has two main parts. In the first part, we review the ‘self-reflections’ of IR scholars on the state of the discipline. We utilize a comprehensive selection of conference papers, meeting minutes, online/video talks, surveys, and research articles where scholars identify and discuss the state of IR in Turkey and its development. In the second part, we present our assessment of the current state of the IR discipline in Turkey. We discuss what we prefer to call ‘disciplinary underachievement’ in three groups and offer prospects for the way forward: 1) the structure and content of undergraduate and graduate curricula, 2) the state of the IR discipline, and 3) the state of the IR literature. In addition to tracking the development of the discipline locally and locating our training and scholarship in it, this part also discusses the limitations that we experience in action. We discuss our findings and what we believe may become potential directions for the treatment of the above-mentioned limitations.

Turkey’s IR discipline have been studied by multiple scholars since the early 2000s. Discussions mostly revolve around the lack of theory development and methodological quality in Turkey’s IR. The state of IR education has been occasionally discussed at workshops and conferences. A significant attempt to discuss the state of IR education was made in the Workshop on International Relations Studies and Education in Turkey (April 16-17, 2005), a forum that convened Turkish IR scholars who were at different stages of their academic careers. Based on her observations during the workshop, Dedeoğlu identifies that the most frequently encountered limitations in Turkish IR studies are: 1) IR studies do not have a clear problematique, a thesis, or proposition(s), 2) methods and methodological choices are either absent or vague, 3) the conclusions of studies do not conclude the study but are mere summaries of what is written, 4) studies do not rely on the original/main sources but rather benefit from secondary sources, 5) mistakes in referencing and footnotes, and 6) vague and incomprehensible Turkish language in translated studies.[iii] Dedeoğlu also refers to the problems of IR as a profession in Turkey. According to her arguments, professors have a heavy course load, are pushed to teach courses that do not fall into their areas of expertise and are underpaid. These factors are cited as hampering scholars’ potential and leading them to neglect some of their responsibilities.[iv]

In a follow-up roundtable organized by the International Relations Council (Uluslararası İlişkiler Konseyi) at Middle East Technical University (METU), Turkish IR scholars discussed the shortcomings and the state of IR in Turkey.[v] Aydın, citing what Suat Bilge put forward in 1961, identifies two anomalies in Turkish IR: there is a ‘lack of interest in reading’ among Turkish IR students, and there is too much emphasis on current events rather than analysis in IR studies. He argues that in 2005, after forty-five years, Turkish IR scholars had kept complaining about similar problems. Based on his observations at the Ilgaz Conference (the conference on April 16-17, mentioned above) he adds that significant limitations in Turkish IR are the lack of conceptual analysis, the lack of methods/methodology, and the lack of established local epistemic communities.[vi] In the same roundtable, when asked about the state of IR, Karaosmanoğlu summarizes the progress of IR in Turkey in four stages. The first is the Mekteb-i Mülkiye stage where IR was taught as a vocation. As IR departments mainly aimed at training prospective diplomats, the focus of IR education around the 1960s was “the Turkish state’s needs and explanation of Turkey’s foreign policy and Turkish diplomatic history.”[vii] The second stage is when IR theory is more adequately referred to (relative to the previous stage) during the late 1960s and 1970s. This shift was mainly dominated by the political science departments of METU, Boğaziçi University, and İstanbul University. The third stage is in the 1980s, which corresponded with Turkey’s economic opening to the international economic system in the Özal period. As Karaosmanoğlu argues, this paved the way for the entrance of new sub-fields into Turkish IR, such as International Political Economy and liberal IR theories. The fourth stage was the post-Cold War period when certain Turkish universities opened graduate programs specifically on International Relations, separating it from Political Science. IR “moved from simplicity and inflexibility of the Cold War to cover much more diversity and complexity of international relations.”[viii]

From the discussion of the abovementioned four stages, one may identify the direction of the evolution of IR in Turkey from a more history-oriented discipline towards a theory-oriented one. In the first stage, the IR discipline seems to be more interested in descriptions of Turkish foreign policy, while in the second stage there is a limited introduction of IR theory that mainly revolves around the Cold War conception of security. The third stage welcomes a limited diversification in theoretical approaches, while in the fourth stage there is a relatively more comprehensive diversification in the knowledge and use of IR theory among Turkish IR scholars.[ix] Appreciating the level of development in the quality of IR scholarship in Turkey, Karaosmanoğlu also identifies a continuing deficiency. He points out that IR research in Turkey is opening itself to ‘global’ academia as the number of international publications increases; however, Turkish IR scholars “have not contributed to the development of IR theory yet.”[x] Eralp agrees with Karaosmanoğlu and claims that although there is a significant improvement in IR education in Turkey, Turkey’s IR scholars still need progress in terms of theory. Eralp also adds two more directions for improvement. The first one is the "issue of methodology," which is especially significant in teaching and doing research in IR, and the second one is the need for more collaboration among IR departments and scholars across Turkey.[xi]

Another significant point is made by Bilgin in her article that situates the state of Turkey’s IR discipline on the wider global “center-periphery relations” debate.[xii] The argument is based on several other IR scholars’ observation that “standard” concepts and theories of IR that are developed in the ‘center’—the ‘developed’ world—remain insufficient in explaining the problems of the ‘periphery’—the ‘developing’ world. As the development of conceptual frameworks continues to be monopolized by the center, a hierarchical division of labor with those in the periphery is also being reproduced. According to this division of labor, those in the center develop the standard theories and concepts, while those in periphery adopt them -occasionally regardless of their capacity to explain or understand other experiences- to apply to their respective empirical cases. Focusing specifically on security studies, Bilgin argues that Turkish scholars do not necessarily debate whether the ‘standard’ conception of security applies to the Turkish case.[xiii] Yet, this standard conception of security that mainly focuses on external threats and realist alliance theories has been insufficient to explain the insecurities that Turkey has faced. In the period when the IR discipline was newly established in the country, the standard concepts and theories were accepted without question, used in academic studies, and taught to students of IR in Turkey.[xiv] Bilgin points at an important path forward for IR scholars in Turkey. Scholars in Turkey may ‘debate’ the applicability of existing ‘standard’ concepts and theories and, when necessary, contribute with new and more applicable ones through conceptual and theoretical criticism inspired by Turkey’s experiences.[xv]

We observe a flourishing debate by the late 2000s on scholars’ self-reflections regarding the state of IR discipline. For instance, based on an interview conducted with Turkish IR scholars, Aydın assesses the scientific research and teaching perspectives.[xvi] Aydın claims that IR scholarship in the country has rapidly improved and transformed over the last two decades.[xvii] By the 2000s, scientific debates in Turkey’s IR had, to some extent, reached a level parallel to IR scholarship in the West.[xviii] IR scholars have overcome the limitation of ‘just studying Turkey,’ have developed an interest in global politics, and have started to discuss the possibility of developing a ‘local theory’ of international relations and providing specific courses on various sub-fields of IR, including but not limited to political economy, strategic studies, and security studies.[xix] Observing a similar diversification in IR education, Keyman and Ülkü made a comparative assessment of the undergraduate curricula of various IR departments in Turkey.[xx] They emphasize that, based on the courses offered, IR undergraduate education has limitations on the topics like political theory, globalization, security and conflict studies, and methods. The authors suggest that IR departments need to improve their capacity to teach political theory to support IR theory knowledge and should offer specific courses on globalization, security studies, and research methods. They identify that despite the importance of methods in the development of the IR discipline, undergraduate curricula have somehow overlooked the significance of methodology and the need to include specific courses on research methods.

The literature also discussed limitations in graduate education. For instance, Özcan identifies a list of structural and student-related limitations of graduate education.[xxi] In terms of structural limitations, he claims that social sciences in general do not receive adequate attention and funding. This fact results in limited library resources, causes indifference in training graduate students and, as a result, a limited number of faculty members, and turns out as a high course load for professors and limited variety in course offerings. Another structural limitation he points out is the insufficient training that graduate students take in their undergraduate education. Third, IR graduate programs are too ‘Turkey-oriented,’ and limited attention is devoted to other countries and areas.[xxii] Özcan also highlights the consequences of these problems. For instance, academic advisors and jury members tend not to devote enough time and proper attention to graduate theses and dissertations. He identifies the inadequacy in the number of books and articles written in Turkish on main topics such as IR theory and foreign policy analysis.[xxiii] Özcan also also student-related limitations in graduate education. First and foremost, there is a lack of motivation among students, as they generally tend to see graduate education not as a way of becoming a scholar, but instead as a way of postponing unemployment or compulsory military service. He also touches upon limited financial resources, bursaries, and stipends given to graduate students as a potential reason for the loss of motivation among graduate students.[xxiv]

Scholars also discussed the issue of local theory-building in Turkish IR. Kurubaş identifies two important characteristics of IR in Turkey that hampers the development of a local theoretical approach: ‘historical-factualism’ and ‘interdisciplinary research.’[xxv] He argues that while these are not negative or undesired characteristics, Turkish IR scholars should define the limits of historical analysis and interdisciplinarity to provide more space for local theory development and scientific and analytical research, thereby defining the limits of the IR discipline.[xxvi] The author argues that since historical factualism leads to descriptive but not necessarily analytical studies, IR scholars should move towards a more theoretical perspective. He adds that rather than defining itself as an ‘interdisciplinary discipline,’ IR should move towards becoming an ‘independent and original discipline’ to achieve scientific progress.[xxvii] Kurubaş suggests that offering research methods in social sciences and philosophy of social sciences to IR students may be a way to overcome this limitation.[xxviii] Looking at the issue from an alternative perspective, Yalçınkaya and Efegil stress the estrangement or alienation in IR education.[xxix] They argue that Turkish scholars have left the responsibility of developing theories to Western theoreticians while concentrating on writing descriptive studies. As a result, while contributions of non-Western local experiences to IR theories remain limited, theoretical approaches that are produced by Western scholars based on the experiences of Western societies are accepted as universally valid approaches.[xxx] They make a call to Turkish IR scholars to focus more on theory development rather than contributing to this dependent relationship. They suggest that while using English or other foreign languages is an integral part of IR pedagogy, Turkish IR scholars should publish in Turkish, and IR education should be given in Turkish.[xxxi]

The debate on theory development continued as other scholars also comprehensively searched for the potential for local theory development.[xxxii] By the late 2000s and 2010s, Aydinli and Mathews produced a couple of pieces where they elaborated on the possibility of developing original theories, or what they prefer to call ‘homegrown theorizing,’ and maybe even developing an ‘Anatolian School of IR.’[xxxiii] They assess the development of Turkish IR with reference to the above-mentioned ‘four stages’ defined by Karaosmanoğlu[xxxiv] and add that ‘non-elite IR scholars’ (local periphery) have used theory as a way to balance the dominance of ‘elite IR scholars’ in the field (Mülkiye Tradition - local core).[xxxv] They identify that by the early 1990s, many Turkish IR students were sent abroad for graduate education. When those scholars returned from North American and European universities, they had a more theory-oriented research interest, which led to a rise in theoretical studies produced in Turkey.[xxxvi] Yet, Aydınlı and Mathews highlight that having a theory-oriented research interest does not necessarily result in the development of new theories. They base this argument on their assessment of ‘theorizing’ under four categories: 1) pure theorizing, 2) application theorizing, 3) translation theorizing, and 4) homegrown theorizing.[xxxvii]

The authors observe that Turkish IR has been unable to move beyond application and translation scholarship and discuss potential reasons for the continuing “underachievement of homegrown-theorizing.”[xxxviii] One of the reasons they address is the above-mentioned use of theory by new generations of “foreign-trained” IR scholars to balance the dominance of the “elites” at the local core: “With theory being used as a balance of power tool, its practice often remains elusive, unsubstantiated, and shallow.”[xxxix] They highlight that some professors who did not take any comprehensive exams on theory during their graduate education are assigned to offer graduate-level IR theory courses, give training to new generations of IR scholars, and even come to be known as “theorists” just because they completed graduate education abroad. This resulted in a non-comprehensive understanding of theory among graduate students as those scholars offer a “limited picture of IR theory – focusing on whatever theory(ies) the professor is familiar with, from selected epistemological and methodological approaches to formal IR theories.”[xl] Aydınlı and Mathews also highlight the “memorization-based” education system, lack of methodology training, limited pay-back (media coverage, television spots, newspaper columns) of theoretical studies, publication criteria, and standards in Turkey that discourage conceptual and theoretical studies, and lack of “a cohesive, conscious, organized, and institutionalized Turkish IR disciplinary community” as possible reasons.[xli] Yet, they do not only blame Turkey-based (global periphery) causes, but also argue that the global core, “where training patterns, advisor–student relationships, core prejudices, and scholarly competition all tend to push the periphery student and scholar away from engaging fully in theoretical discussions,” also has responsibility.[xlii] They address the “IR theory classroom” as a starting point and “front” for local theoretical improvement.[xliii]

Based on the Teaching, Research, and International Politics (TRIP) survey made with IR scholars in 2009, Aydın and Yazgan put forward several indicators which, they argue, prove that IR scholars in Turkey “have made progress” in developing a local disciplinary community, and that the IR discipline has significantly matured in the country, especially during the 2000s.[xliv] They come up with certain indicators of such progress: an increase in the number and quality of ‘global level’ publications; establishment of regular IR conferences that convene scholars from different parts of the world in Turkey; and increased participation of Turkish IR scholars in international conferences to become part of the global IR community. Other indicators are the establishment of new IR journals and quality improvement in the existing ones, and finally, the increasing number of funding opportunities by higher education institutions.[xlv]

Aydın and Yazgan’s findings show that scholars mainly focus on foreign policy, Turkey, and great power rivalry, while realism is relatively more widespread than other theories of IR.[xlvi] Compared to the previous period, the authors appreciate this level of development and the relative diversity in the local community. When compared with the follow-up surveys in 2011, 2014, and 2018, their findings indicate that IR scholars continued to have a narrow theoretical focus. Despite the level of complexity in IR theory literature at the global level, Turkey’s IR discipline seems to get increasingly dominated by the three mainstream theoretical approaches: Realism, Constructivism, and Liberalism.[xlvii] Referring to the previous discussion on the disciplinary core and periphery relations,[xlviii] Aydın and Dizdaroğlu also observe that IR in the country has continued to remain at the periphery as the function of the studies produced in Turkey is shifting from “telling Turkey’s story to the world" to “telling the story from Turkey to Turkey.”[xlix]

The findings of the above-mentioned consecutive surveys also indicate that despite all academic meetings where scholars problematize, identify, diagnose, and prescribe solutions for the underachievement in theory, and despite all the ‘urge’ and ‘call’ for local theory development, theoretical studies in Turkey’s IR discipline has kept reproducing the local disciplinary community as an emulator of what has been produced at the core. Aydınlı and Biltekin relate this situation to the lack of methodological diversity and, therefore, knowledge accumulation.[l] They claim that due to the lack of methodological diversity, IR community in the country remained “fragmented,” and studies have not been able to engage in dialogue with each other. This inability to communicate hampers scholarly debates, which resulted in an underachievement in knowledge production and theory development. Referring to TRIP Surveys and their analysis of 251 articles written by Turkish scholars, they argue that the methodological choices of Turkish scholars are predominantly “qualitative.”[li] They suggest that Turkish IR scholars may benefit from utilizing more “quantitative” methodology, as it would require the researchers to define the concepts and clarify the indicators they use, collect data to produce comparable empirical results, and create studies that have methodological clarity. In turn, they offer that the methodological clarity required by quantitative studies may become a solution to the fragmentation in the local disciplinary community and promote progressive scholarly debates.[lii] In line with this argument, Aydınlı, later on, argues that one of the most important problems of IR in Turkey is not the lack of theoretical studies but instead the lack of methodological quality.[liii] He argues that “methodology, its tools and approaches and the expertise needed to apply them in a competent and skilled manner, constitutes the universal language of an academic discipline.”[liv] He observes two interrelated limitations: “lack of appreciation for the importance of methodology,” and “overall inadequacy in the knowledge of and competence in applying methodological approaches and tools.”[lv] Aydınlı argues that these limitations also affect the training that the new generation of IR scholars get in Turkey, which in turn affects the quality of theses, dissertations, and studies.[lvi]

Observing the disciplinary self-reflections, Sula suggests that Turkish IR scholars should move from the diagnosis and prescription of problems to the actual treatment of them.[lvii] While appreciating Aydınlı and Biltekin’s suggestions on methodological clarity, he argues that an exclusionary position on the ‘qualitative methods versus quantitative methods’ distinction may hamper the authors’ call for the development of a ‘non-fragmented’ local community. Alternatively, he proposes that what the IR discipline in Turkey needs is not “more quantitative methods but instead more ‘methods’ in general.”[lviii] Conceptual and methodological clarity should not be seen as exclusive characteristics of quantitative approaches, but instead, they should be seen as characteristics of all scholarly studies. Sula highlights a tendency to label every ‘non-quantitative’ study as ‘qualitative,’ which is also an important limitation that Turkish IR scholars should overcome.[lix] To further clarify this claim, he presents data from another study that analyzes all “securitization” articles written in Turkish and published in an IR journal indexed in the Turkish citation index, ULAKBIM. His data indicates that none (0 out of 34) of those articles label their methodological approach as ‘quantitative,’ and more than half of the articles (18 out of 34) do not talk about their methodological approach at all. In the remaining half (16 out of 34), the authors imply the use of a “qualitative approach” in their research. These figures indicate that Turkish scholars predominantly use qualitative methods in their articles.[lx] However, Sula argues that an in-depth study of these figures better clarifies the problem. He proposes that Scholars may have a better grasp of the methodological quality problem if they get beyond the ‘qualitative versus quantitative’ dichotomy and make a proper meta-theoretical distinction between the term ‘methodology – as defining the scholarly approach’ and ‘methods – defining the technique/tool used to collect information.’[lxi] After making this distinction, he identifies that only 26% (9 out of 34) of the authors specified which research method they used in their article.[lxii]

In addition to the analysis of the securitization literature, Sula also argues that “qualitative research does not imply methods-free research or an ‘anything goes’ approach” and highlights that “specifying the methodological approach does not directly result in methodological clarity.”[lxiii] While agreeing with the existing literature on the need for improvement in methodology training and encouraging methodological clarity, he highlights that the way forward does not necessarily have to be a more ‘quantitative’ one. Sula prescribes that rather than establishing ideological and exclusionary positions between quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodological approaches, training new generations of graduate students through data-collection projects and the establishment of a social science data repository where Turkish scholars may openly share data may turn out to be a feasible direction in encouraging methodological clarity in Turkey’s IR.[lxiv] Turkish IR scholars should increase the number of ‘data-collection’ projects and let graduate students get training in action by participating in all stages of data collection.

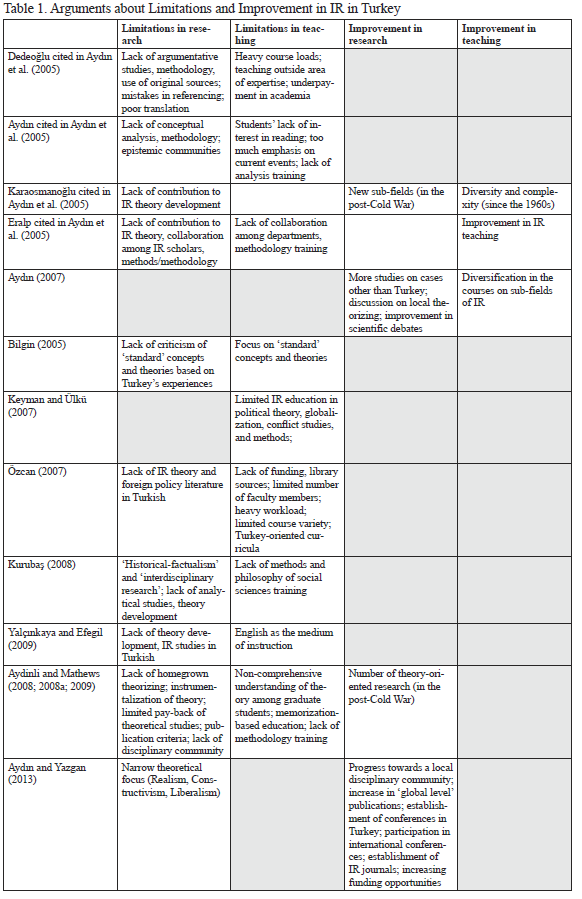

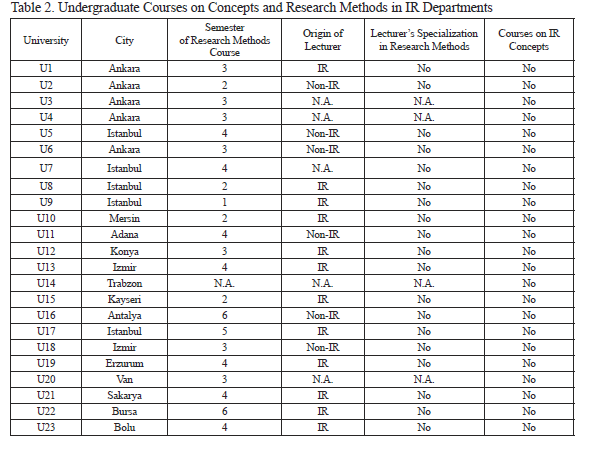

Table 1 below illustrates the main arguments put forward by the abovementioned literature. Although respective studies have their understanding of what failure/limitation and improvement/progress are, one can identify similar points made by most of these scholars. Diversification of subjects and subfields in both teaching and research is cited by most scholars as a sign of improvement. An increase in theoretical debates and theory-building attempts are also considered to be an indicator of progress in the IR discipline. Researching cases other than Turkey, taking part in ‘international’ conferences, and publishing in ‘international’ journals are usually regarded as signs of participating in ‘global IR.’ We interpret that there is a tendency among Turkish scholars to regard this—becoming part of global IR (usually IR in the “West”)—as an improvement in the IR discipline. Definitions of underdevelopment and limitation further strengthen this interpretation. In terms of IR research in Turkey, insufficient efforts to conduct theoretical research, as well as to establish ‘home-grown’ theoretical and conceptual frameworks that are fed by Turkey’s experiences, are widely cited as obstacles to a developed discipline in Turkey. As the table illustrates, recently, some scholars also argue that the lack of the proper use of methods or methodological rigor is the main reason behind disciplinary underachievement, which has a mutually constitutive relationship with insufficiency in methods and methodology training in undergraduate and graduate education. What makes this deficiency part of the global IR debate is that these scholars present methodology as a common language that would help Turkish IR researchers to communicate with the outside world, or ‘global IR.’ Moreover, Turkish as a medium of instruction and language of research in publications is also considered to be one of the crucial points of discussion for disciplinary development.

Table 1. Arguments about Limitations and Improvement in IR in Turkey

Reviewing the previous literature on the state of the IR discipline, we identify three generations of IR scholars in Turkey. The first generation of scholars, those who correspond with Karaosmanoğlu’s[lxv] abovementioned first stage, tended to focus more on diplomatic history, international law, and descriptive explanations of Turkish foreign policy, as their main aim was to train students for diplomatic service. The second generation, those who have trained abroad as Aydınlı and Mathews[lxvi] mentioned, tended to focus more on IR theoretical analysis, as they used theory in their encounters with the first generation and as a way of balancing the dominance of the local elite (which is again represented mostly by the first generation). As the IR discipline developed in Turkey and the number of IR departments and scholars increased, we are now observing a third generation in the making that has hybrid characteristics. A significant portion of scholars of this hybrid third generation are trained by a mixture of first- and second-generation scholars (probably more by the second one), and the remaining portion of this generation is trained or continues to be trained abroad. This hybrid generation has gone through most limitations that are indicated in the self-reflections of the second generation. As such, the responsibility of overcoming some of those already diagnosed limitations and finding prescriptions or, if possible, treatment for the problems faced by the local IR community would most likely fall upon the shoulders of the third generation; at least on those who are willing to take it.

As the authors of this article, we are scholars trained mostly by the abovementioned second-generation IR scholars. This is significant not only for locating ourselves in this research, but also, because we have experienced most of the structural problems that IR scholars have written and talked about, and we may testify for them.[lxvii] Together with limitations already diagnosed in the local IR discipline, we also have observations on the limitations that affect our scholarship in two aspects. First, these limitations affect the training we offer in our undergraduate and graduate-level IR classes. Second, they affect the way we do research and determine the agenda that we work on. While discussing the contemporary state of the discipline, adding to the existing literature, we discuss these limitations under three groups and offer prospects for the way forward: 1) the state of undergraduate and graduate education in Turkey, 2) the state of the IR discipline in Turkey, and 3) the state of IR literature in Turkish.

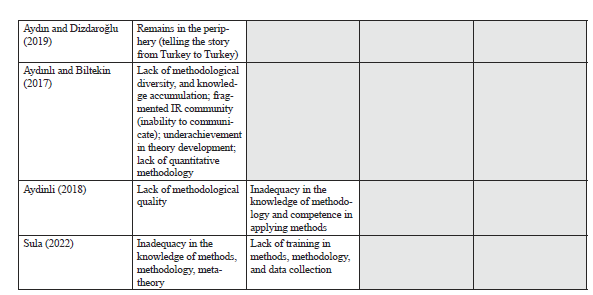

Reasons for the ‘disciplinary underachievement’ in the Turkish IR discipline mainly emanate from pedagogical limitations in IR education. Both undergraduate and graduate IR education in Turkey have their distinct but interrelated issues. It is important to start with curricula and sourcebooks. First, most IR curricula in turkey lack specific courses on disciplinary concepts. The data we collected from twenty-three IR departments across Turkey (see Table 2) confirms this argument. Students usually encounter IR concepts in IR theory and introduction to world politics courses. Consequently, these courses cannot devote enough time to get students engaged with the philosophical roots of the concepts, how their definitions and meanings have changed across different theories, and the ways they can be utilized to analyze global politics. Students, most of the time, take theory courses without being able to define ‘theory’ as a concept. Such a pedagogical limitation reduces future scholars’ ability to think conceptually in academic research, which hampers their capacity to make conceptual and theoretical contributions from ‘local’ to ‘global.’ We believe that this feeds what Aydınlı and Matthews mention as Turkish IR’s tendency to only produce ‘translation conceptualizing.’

IR departments tend to locate research methods courses in freshman or sophomore years.[lxviii] While most (19 out of 23) IR departments are offering method courses in the first two years, only a few (3 out of 23) have their method courses in the third year, and one IR department does not have any method courses in the curriculum. Considering that most of these students are not yet taught courses on the fundamental concepts and principles of IR, as well as basic requirements of research in social sciences, it is too early for them to be able to properly master methods of inquiry. This situation has a wider impact on the quality of methods courses as it causes the lecturers to simplify the content of the course to adapt it to the current level of the students. As a result, most courses on methods cannot provide a detailed account of the methodological roots and principles of research, nor a systematic application of certain methods as tools to conduct empirical research. An interesting finding is that in most IR departments, these courses are not offered by scholars specialized in methods and methodology. In some cases, these courses are taught by scholars from other disciplines. Specifically, methods courses are offered or coordinated by IR scholars in twelve departments, while six departments assign these courses to scholars from other disciplines.[lxix] Based on their own claim in the information packages on their official university websites, none of them specifically specialize in research methods and methodology.

Table 2. Undergraduate Courses on Concepts and Research Methods in IR Departments

The abovementioned issues are also observed in graduate education. Limitations on teaching concepts, theories, and methods in the undergraduate classroom have a multiplier effect on problems in graduate education. Students that lack conceptual and theoretical thinking, as well as proper skills in applying methods, have difficulties in improving their abilities in graduate education. Most graduate IR programs do not have courses that teach the main IR concepts and their philosophical underpinnings in their curricula. Research methods courses are not designed specifically for students of IR in most of these programs. Again, and even more questionable than undergraduate education, research methods courses are given by lecturers from other disciplines or scholars without a methodology expertise. This deficiency hampers IR students’ capacity to properly utilize methods in their research, as is evident in the master’s and Ph.D. dissertations, and which is also related to limitations in graduate supervision, at least for two interrelated reasons.[lxx] First, advisors’ competencies in main concepts and theoretical and methodological approaches might be insufficient. As a result, these limitations are constantly in reproduction. The second factor, also addressed in the literature, might be related to the heavy workloads of advisors. Due to a lack of proper planning in the master’s and Ph.D. admission processes, professors in most IR departments must undertake more supervision duties than they can manage, which reduces the time they can devote to each student. This problem results in the production of theses and dissertations that only satisfy the minimum requirements of graduation, far from having done proper considerations of conceptual, theoretical, and methodological issues.

Our review of the literature suggests that the state of the IR discipline has so far been referred to as ‘underachieved’ or ‘underdeveloped’ on theoretical and methodological grounds. Considering these limitations at different levels of education, it is probably not realistic to expect original contributions or the integration of ‘local knowledge and experiences’ to the existing global debates on concepts and theories.[lxxi] Based on our teaching and supervision experiences, we also argue that there are limited conceptual contributions to disciplinary concepts in terms of meaning-clarification (or conceptualization), classification, and application in theses and dissertations produced in Turkey. Rather than engaging in systematic conceptual analysis, dissertations tend to utilize concepts to explain or understand a particular case study. According to data we gathered from the National Thesis Center (Ulusal Tez Merkezi) of the Higher Education Council (Yükseköğretim Kurulu), there are only twenty-nine theses and dissertations that engage in conceptual analysis among a total of 5,769 produced in IR and related sub-fields[lxxii] between 2000 and 2022. This means that only 0.5% of the dissertations produced in IR and related departments in Turkey engage in conceptual analysis, which indicates that Turkish IR academia seems to have little interest in studying and developing disciplinary concepts.

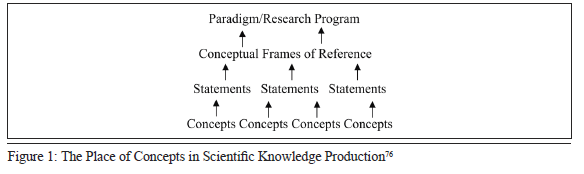

We argue that conceptual thinking and analysis are significant due to their relations with disciplinary knowledge production and theory building. Concepts have a central role in knowledge production because they make it possible to distinguish a particular object, event, action, or set of relations from whatever ‘is not’ that object, event, action, or set of relations within a discipline.[lxxiii] This is to say that concepts are basic building blocks of a discipline (see Figure 1). For example, IR as a discipline is built and developed upon a series of disciplinary concepts and disciplinary reflections on those concepts such as international, diplomacy, war, peace, anarchy, state, power, security, hegemony, interdependence, emancipation, and so on. Therefore, conceptual analysis of disciplinary concepts helps to identify borders of discipline, improve scholarly communication, and produce knowledge.

Conceptual analysis as a method of inquiry can be descriptive or performative. Descriptive conceptual analysis is to clarify and explicate a concept, demonstrate its links with other concepts, and identify different utilizations of them. Conceptual clarity is one of the main elements to achieve scholarly communication, seen as the key condition for the advancement of knowledge within a discipline.[lxxiv] Performative conceptual analysis engages in conceptual history or genealogy by questioning how the concept at hand has arrived at its current meaning. Hence, performative analysis relies on the argument that it is “impossible to isolate concepts from the theories in which they are embedded, and which constitute part of their very meaning.”[lxxv] This refers to a mutually constitutive relationship between conceptual formation and theoretical formation. Furthermore, as Guzzini states, conceptual analysis is performative in the sense that it affects the order of social relations and is also part of the social construction of knowledge.[lxxvi] Thus, the lack of interest in concept development contributes to the discipline’s limited capacity in identifying, labeling, classifying, and relating the objects, events, and phenomena to develop original theoretical approaches and arguments. This further limits Turkish IR’s capacity to contribute to the global based on local experiences and approaches.

Figure 1: The Place of Concepts in Scientific Knowledge Production[lxxvii]

Graduate theses and dissertations perform better in the use of theory than in conceptual analysis. However, we agree with the previously defined diagnosis in the literature that most of these studies conduct ‘translation’ or ‘application theorizing’ without necessarily making original theoretical contributions. Moreover, theoretical and empirical chapters of the dissertations appear as separate researches that is not necessarily contributing to the dissertations’ main arguments and analyses. Most dissertations share this similar structure: limited discussion on methods in the introductory chapters, a literature review chapter on theory, and a literature review chapter on the case, which is usually not connected to the theory. The number of dissertations that utilize appropriate methods is also considerably low. Most of those that utilize some sort of methods also cannot fulfill the sufficient criteria of methodological clarity and transparency as they do not explain the actual steps of data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Here, the distinction between methodology and research methods should be highlighted. While the former points to “the logical structure and procedure of scientific inquiry”[lxxviii] and specifies the relationship between the researcher and the world that is being researched, the latter refers to actual techniques for collecting, processing, and analyzing data or information. Methodology, whether objectivist or interpretivist determines methods. Sound methods based on deliberate methodology selection provide the research community with an opportunity to test the validity of claims through an interrogation of the processes of data collection, processing, and findings. In this regard, lack of methods and methodological clarity limits not only replicability, but also scholarly communication, and stands as a challenge to the potential to further progress in concept- and theory-building.

Another limitation that we want to point out is related to the literature on IR in Turkish. Due to the history and development of IR as an “American social science” (see Hoffman, 1977), the English language has worldwide dominance in IR course materials, which is also the case in Turkey. Therefore, most IR departments in the country rely heavily on translated course material. A professor who teaches IR in the Turkish language has roughly three options: 1) they may read in English, translate the reading material, and summarize the content as lecture notes/slides, 2) they may take the challenge to produce a textbook in Turkish on the course they offer, and assign the end product to students, 3) they may rely on the literature in Turkish for quality material to assign to students. The first option is neither feasible nor sustainable in the long run. It is not feasible because through lecture notes and slides, there can only be a limited amount of knowledge and skill transfer to students. In addition, this option limits the personal research and self-development capacity of students by getting them accustomed to ready-made course material. It is not sustainable because considering the average course load of professors in most universities, academics do not have enough time to translate/summarize/prepare lecture notes for each course they offer. The same reasons apply to the second option. In addition to giving a limited perspective to the students, it is not practical or even possible for a professor to write a textbook on every course they have to offer. The third option, which is to utilize the existing material written in Turkish, remains the most feasible one with the caveat of all the limitations we touched upon so far regarding the state of Turkish IR literature.

To provide an example from IR theory courses, most theory books in Turkish seem to adopt ‘translation theorizing,’ essentially summarizing the existing literature in English without a sufficient in-depth analysis of theoretical and meta-theoretical assumptions and arguments. Moreover, those books are not necessarily interested in engaging with the interpretation and categorization of theoretical approaches in IR or contributing to ‘global’ debates within IR theory literature. On the other hand, students that are educated in full or partial English-medium IR departments that assign source books in English have their own issues in mastering theories due to the language barrier. As a result, most students experience difficulties in learning theories thoroughly, and in some cases, their knowledge of theories remains descriptive and maybe even superficial. Utilizing this literature without carefully selecting the material would be nothing more than reproducing the current limitations or postponing the solution to the problem.[lxxix]

We agree with Özcan’s above mentioned argument that the lack of a rich literature on IR in Turkish stands as a challenge that hampers further development in IR. Writing books, articles, and book chapters in Turkish based on solid methodological, theoretical, and conceptual analysis may be a way out of this problem for those Turkish scholars willing to take the responsibility. It is an obstacle both for research on the development of concepts and theories that are based on Turkey’s (local) experience and for progress in teaching in universities with Turkish as their medium of instruction. The responsibility, unfortunately, falls heavily on the ‘hybrid third generation’ of Turkish IR scholars mentioned above. If new generations of Turkish IR scholars continue to be inadequately trained and unable to develop original theoretical, methodological, and conceptual studies, the problems faced by IR programs offering Turkish education will in turn become a ‘chicken and egg problem.’ We need more IR studies written in Turkish, but the only ones who seem to care about this need and may be willing to address the problems in the Turkish IR literature are those that are educated in Turkish. If IR scholars ignore this need, new generations of scholars educated in Turkish will most likely continue to reproduce the very Turkish IR literature that seems to be problematized (or not problematized at all) by Turkish IR scholars.

Last but not least, it is also necessary to briefly bring up the academic quality assessment and promotion criteria in Turkish higher education as hampering IR education in the country. Such criteria encourage scholars to produce in English and publish in ‘high impact factor’ journals, while scholars who contribute to Turkish literature are being pushed to the margins. Universities’ prioritization of English-written academic publications and encouragement of assigning only English-written material in course syllabi hampers the development of Turkish IR literature. Those ‘prestigious’ IR departments also apply ‘Ph.D. degrees from Western (mostly American) institutions’ as recruitment criteria, which discourages young researchers and students in their attempts and enthusiasm to contribute to the local development of the discipline. To say the least, this trend contributes to the ‘disciplinary underachievement’ of Turkish IR.

Our review of Turkish IR scholars’ self-reflections suggests that IR academia has updated their initial diagnosis that ‘there is not enough theory’ into a new one suggesting that ‘there is some theory but not methods.’ We suggest that IR academia in Turkey does not have its distinctive language, as it has limited capacity to teach even its own ‘theories, concepts, and methods’ to the new generations of scholars. The distinctiveness and advancements of a discipline are inherently related to the development of its disciplinary concepts, theoretical approaches, and methods of inquiry. Otherwise, the discipline would become a mere collection of knowledge accumulated in other related disciplines without engaging in comprehensive knowledge production.

Probably due to many interrelated limitations mentioned above, IR in Turkey produces a significant number of graduate dissertations/theses without methods, theories without empirics, and descriptions without analyses. The conceptual, theoretical, and methodological deficiencies in dissertations and theses are indicators of the disciplinary underachievement of IR in Turkey. We believe that only diagnosing limitations in the state of the discipline in Turkey is a futile effort to overcome the problem. Moreover, the previous generations of IR scholars seem to have allocated a significant amount of time to consider, diagnose, and offer prescriptions for the problem without necessarily treating it. We suggest that despite all the limitations, with a hybrid third generation in the making, Turkish IR academia has reached a transition period to move beyond self-reflective diagnosis and prescriptions toward treatment. For now, we see a potential for treatment in three directions.

First, in agreement with the prescriptions in the literature, since methodology is the lingua Franca of academia,[lxxx] we believe that one of the first things to do is to improve methodology training at the graduate level. In this direction, we agree with Sula’s previous suggestion to establish a Turkish data repository and disseminate data-collection-based learn-in-action projects as a feasible direction to overcome this limitation.[lxxxi] Second, we think that there is a need to improve the IR literature in Turkish, both in quantity and quality. Our observation is that even students who are trained in 100% English education programs are inclined to read complimentary Turkish IR material during their education. Improving the quality and quantity of Turkish IR material will certainly contribute to the new generations of Turkish IR scholars’ comprehension of the disciplinary theories, concepts, and methods. We believe that increasing the number of theoretical and conceptual IR studies written in Turkish would be a step toward further treatment.[lxxxii]

Finally, we appreciate the development of a local IR disciplinary community, albeit loosely. However, for the development of a true community, Turkish IR scholars need to engage in deeper self-reflections unveiling the local center-periphery relations, cliques, under-appreciations, unfair treatments, and discouragements that result in nothing more than hampering the development of Turkey’s IR discipline in general.

Notes

[i] İsmail Erkam Sula, Corresponding author, Associate Professor, Department of International Relations, Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University. Email: iesula@aybu.edu.tr ORCID: 0000-0001-6011-4032

Buğra Sarı, Associate Professor, Department of International Relations, Mersin University;

Department of International Security, Turkish National Police Academy. Email: bugrasari1988@gmail.com ORCID: 0000-0001-6428-1292

Çağla Lüleci-Sula, Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science and International Relations, TED University, Email: cagla.luleci@tedu.edu.tr ORCID: 0000-0002-0534-8271

[ii] An earlier version of this research was presented at the 6th All Annual Azimuth Workshop: “Think Global Act Local: The Globalization of Turkish IR”, Bilkent University. November 6-7, 2021, Ankara. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions received from the participants of and discussions at the workshop. The authors also appreciate the comments and contributions of the anonymous reviewers of All-Azimuth.

[iii] Beril Dedeoğlu, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Çalışmaları ve Eğitimi Çalıştayı (16-17 Nisan 2005) Üzerine,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 2, no. 6 (2005): 152.

[iv] Ibid., 153.

[v] Mustafa Aydın cited in Şule Kut et al., “Workshop Report International Relations Studies and Education in Turkey” Uluslararası İlişkiler 2, no. 6 (2005): 131–47.

[vi] Ibid., 136.

[vii] Ibid., 138.

[viii] Ibid., 140.

[ix] Ibid., 137–40.

[x] Ibid., 140.

[xi] Ibid., 143.

[xii] Pınar Bilgin, “Uluslararası İlişkiler Çalışmalarında ‘Merkez-Çevre’: Türkiye Nerede?,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 2, no. 6 (2005): 3–14.

[xiii] Ibid., 7–8.

[xiv] Ibid., 8.

[xv] Ibid., 11.

[xvi] Mustafa Aydın, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenlerinin Bilimsel Araştırma ve Uygulamaları ile Disipline Bakış Açıları ve Siyasi Tutumları Anketi,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 4, no. 15 (2007): 1–31.

[xvii] Here, we should take note that there is no “common” definition of “improvement” or “failure” in IR among the scholars that we cited throughout this article. However, we understand that scholars usually tend to compare the state of IR in Turkey with the state of global IR (or IR in the "West") or count the number of research articles written by Turkish scholars in WoS/Scopus Indexed and refereed international journals to discuss “improvement and failure.”

[xviii] Ibid., 3.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] E. Fuat Keyman and N Esra Ülkü, “Türkiye Üniversitelerinde Uluslararası İlişkiler Ders Müfredatı,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 4, no. 13 (2007): 99–106.

[xxi] Gencer Özcan, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Alanında Lisansüstü Eğitimin Sorunları,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 4, no. 13 (2007): 107.

[xxii] Ibid., 107–9.

[xxiii] Ibid., 109–10.

[xxiv] Ibid., 110–11.

[xxv] Erol Kurubaş, “Türkiye Uluslararası İlişkiler Yazınında Tarihsel Olguculuk Ile Disiplinlerarasıcılığın Analitik Yaklaşma Etkisi ve Türkiye Uygulaması,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 5, no. 17 (2008): 129–59.

[xxvi] Ibid., 130–31.

[xxvii] Ibid., 153–54.

[xxviii] Ibid., 154–56.

[xxix] Alaeddin Yalçınkaya and Ertan Efegil, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Eğitiminde ve Araştırmalarında Teorik ve Kavramsal Yaklaşım Temelinde Yabancılaşma Sorunu,” Gazi Akademik Bakış 3, no. 5 (2009): 207–30.

[xxx] Ibid., 228.

[xxxi] Ibid., 226–29.

[xxxii] An important question here is the following: “Why is it that theory development is presented as the key to success?” Theory development is widely cited in the literature as a significant sign of 'disciplinary development' and being part of what is referred to as 'global IR'. Rather than presenting empirical data to existing theoretical frameworks and assumptions with a research design to test hypotheses, what is encouraged in this literature is to construct theories and concepts that reflect the experience of Turkey as a 'non-Western' or 'peripheral' actor of global IR academia.

[xxxiii] Ersel Aydınlı and Julie Mathews, “Türkiye Uluslararasi Ilişkiler Disiplininde Özgün Kuram Potansiyeli: Anadolu Ekolünü Oluşturmak Mümkün Mü?,” Uluslararasi Iliskiler 5, no. 17 (2008): 161–87.

[xxxiv] Aydın et al., “International Relations Studies and Education in Turkey,” 136–40.

[xxxv] Aydınlı and Mathews, “Türkiye Uluslararasi Ilişkiler Disiplininde Özgün Kuram Potansiyeli”

[xxxvi] Ibid.

[xxxvii] Ibid.; Ersel Aydinli and Julie Mathews, “Periphery Theorising for a Truly Internationalised Discipline: Spinning IR Theory out of Anatolia,” Review of International Studies 34, no. 4 (October 1, 2008a): 693–712.

[xxxviii]Ibid., 706-10.

[xxxix] Ersel Aydinli and Julie Mathews, “Turkey: Towards Homegrown Theorizing and Building a Disciplinary Community,” in International Relations Scholarship Around the World, ed. Arlene B. Tickner, Ole Wæver (London: Routledge, 2009), 216.

[xl] Ibid.

[xli] Ibid., 217–18.

[xlii] Ibid., 218.

[xliii] Ibid., 220.

[xliv] Mustafa Aydın and Korhan Yazgan, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenleri Araştırma, Eğitim ve Disiplin Değerlendirmeleri Anketi-2009,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 7, no. 25 (2010): 8.

[xlv] Ibid., 8–9.

[xlvi] Ibid., 30–31.

[xlvii] The four consecutive surveys indicate that the scholars in Turkey who identify their theoretical approach with one of these three theories are 56% in 2009, 65% in 2011, 70% in 2014, and 69% in 2018. Those who identified themselves with critical theory were significant in 2009 with 9%, but relatively declined in 2011 to 5%, and were counted among 'other approaches' in 2014 and 2018. Those who identify themselves with 'other theoretical approaches' also declined significantly from 18% in 2009 (Critical Theory excluded), 11% (with %5 Critical Theory included) in 2011, 10% (with critical theory) in 2014, and 9% in 2018. The percentage of scholars who do not use any theoretical approach increased from 5% in 2009 to 11%in 2011 and remained relatively constant at around 9-10% in the following surveys. See the TRIP Surveys for further comparison: Ibid., 31; Mustafa Aydın and Korhan Yazgan, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenleri Eğitim, Araştırma ve Uluslararası Politika Anketi-2011,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 9, no. 36 (2013): 18; Mustafa Aydın, Fulya Hisarlıoğlu, and Korhan Yazgan, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenleri ve Alana Yönelik Yaklaşımları Üzerine Bir İnceleme: TRIP 2014 Sonuçları,” Uluslararası İlişkiler 12, no. 48 (2016): 15; Mustafa Aydın and Cihan Dizdaroğlu, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler: TRIP 2018 Sonuçları Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme,” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 16, no. 64 (December 1, 2019): 13, https://doi.org/10.33458/uidergisi.652877.

[xlviii] Bilgin, “Uluslararası İlişkiler Çalışmalarında ‘Merkez-Çevre’: Türkiye Nerede?”; Ersel Aydinli and Julie Mathews, “Are the Core and Periphery Irreconcilable? The Curious World of Publishing in Contemporary International Relations,” International Studies Perspectives 1, no. 3 (December 2000): 289–303, https://academic.oup.com/isp/article-lookup/doi/10.1111/1528-3577.00028.

[xlix] Aydın and Dizdaroğlu, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler: TRIP 2018 Sonuçları Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme,” 27; See also Pinar Bilgin and Oktay F Tanrisever, “A Telling Story of IR in the Periphery: Telling Turkey about the World, Telling the World about Turkey,” Journal of International Relations and Development 12, no. 2 (June 11, 2009): 174–79, https://doi.org/10.1057/jird.2009.5; Emre İşeri and Nevra Esentürk, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Çalışmaları: Merkez-Çevre Yaklaşımı,” Elektronik Mesleki Gelişim ve Araştırma Dergisi 2016, no. 2 (2016): 17–33, www.ejoir.org.

[l] Ersel Aydinli and Gonca Biltekin, “Time to Quantify Turkey’s Foreign Affairs: Setting Quality Standards for a Maturing International Relations Discipline,” International Studies Perspectives 18, no. 3 (2017): 268.

[li] Ibid., 268–79.

[lii] Ibid., 279–83.

[liii] Ersel Aydinli, “Opening Speech,” in 2.Nd Politics and International Relations Congress (Trabzon - Turkey: Karadeniz Technical University, 2018) (Available from: https://youtu.be/xz-R7FUWzq0, Retrieved: 30.10.2021).

[liv] Ersel Aydinli, “Methodological Poverty and Disciplinary Underdevelopment in IR,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 8, no. 2 (January 22, 2019): 109–15, http://dergipark.gov.tr/doi/10.20991/allazimuth.513139; Ersel Aydinli, “Methodology as a Lingua Franca in International Relations: Peripheral Self-Reflections on Dialogue with the Core,” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 13, no. 2 (June 1, 2020): 287–312.

[lv]Aydinli, “Methodological Poverty and Disciplinary Underdevelopment in IR.”

[lvi] Ibid.

[lvii] İsmail Erkam Sula, “‘Global’ IR and Self-Reflections in Turkey: Methodology, Data Collection, and the Social Sciences Data Repository,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 11, no. 1 (2022): 12.

[lviii] Ibid., 13.

[lix] Ibid., 14.

[lx] Ibid.; Ismail Erkam Sula, “Güvenlikleştirme Kuramında ‘Söz Edim’ ve ‘Pratikler’: Türkçe Güvenlikleştirme Yazınında ‘Yöntem’ Arayışı,” Güvenlik Stratejileri Dergisi 17, no. 37 (March 30, 2021): 85–118, https://doi.org/10.17752/guvenlikstrtj.905758.

[lxi] Sula, “‘Global’ IR and Self-Reflections in Turkey,” 17.

[lxii] Ibid.; Sula, “Güvenlikleştirme Kuramında ‘Söz Edim’ ve ‘Pratikler.’”

[lxiii] Sula, “‘Global’ IR and Self-Reflections in Turkey,” 18.

[lxiv] Ibid., 19–22.

[lxv] Aydın cited in Kut et al., “Workshop Report International Relations Studies and Education in Turkey.”

[lxvi] Aydinli and Mathews, “Turkey: Towards Homegrown Theorizing and Building a Disciplinary Community”, 211.

[lxvii] Dedeoğlu, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Çalışmaları ve Eğitimi Çalıştayı (16-17 Nisan 2005) Üzerine”; Özcan, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Alanında Lisansüstü Eğitimin Sorunları”; Aydın et al., “International Relations Studies and Education in Turkey.”

[lxviii] We applied the following systematic selection criteria: 1) Each university has an IR department with a consolidated history (established more than 10 years ago), 2) each university has online-accessible information packages including department curricula, and 3) We also limited our selection 5 from Ankara and İstanbul (randomly selected), and at least 1 university from each geographical region of the country. The results and tables do not have information on all universities in Turkey but aim to give a general representation of the state of IR discipline in the country.

[lxix] There is no information regarding the lecturer of the methods course in the information package of five IR departments.

[lxx] Ersel Aydinli and Gonca Biltekin, “Time to Quantify Turkey’s Foreign Affairs: Setting Quality Standards for a Maturing International Relations Discipline,” International Studies Perspectives 18, no. 13 (2017): 267-287; İsmail Erkam Sula, “’Global IR’ and Self-Reflections in Turkey: Methodology, Data Collection, and Data Repository,” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 11, no. 1 (2022): 123-142.

[lxxi] These limitations are directly related to the problem of distinctiveness. Since a discipline can only define itself through its own conceptual, theoretical, and methodological inventory, the IR discipline in Turkey would be then in danger of being nothing more than the application of theoretical assumptions and arguments of the history, law, political science, and sociology disciplines on international politics without developing original disciplinary concepts, theories, and methods.

[lxxii] International Security, International Security, and Terrorism, IR and Globalization.

[lxxiii] Giovanni Sartori, ed., Social Science Concepts: A Systematic Analysis. (Beverley Hills: Sage, 1984) 74.

[lxxiv] David A. Baldwin, “Interdependence and Power: A Conceptual Analysis,” International Organization 34, no. 4 (1980): 472-473.

[lxxv] Stefano Guzzini, “The Concept of Power: A Constructivist Analysis,” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 33, no. 3 (2005): 503.

[lxxvi] Ibid., 513.

[lxxvii] Johann Mouton and H. C. Marais, Basic Concepts in the Methodology of Social Sciences. (Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council, 1996), 125.

[lxxviii] Patrick Thaddeus Jackson, The Conduct of Inquiry in International Relations: Philosophy of Science and Its Implications for the Study of World Politics. (New York: Routledge, 2011), 25.

[lxxix] For now, we leave the task to write a detailed article specifically focusing on the shortcomings of IR literature in Turkish to a courageous future author of such a study.

[lxxx] Aydınlı, “Methodology as a Lingua Franca in International Relations.”

[lxxxi] Sula, “‘Global’ IR and Self-Reflections in Turkey”, 140.

[lxxxii] In this direction, we (Sarı and Sula) started a book series to be composed of new volumes as needed and be written by what we call the ‘hybrid-third generation’ of IR scholars that theoretically discusses the main IR concepts in Turkish. The first volume is published on September 2021. Please see Buğra Sarı and İsmail Erkam Sula (eds.). Kuramsal Perspektiften Temel Uluslararası İlişkiler Kavramları [Basic International Relations Concepts from Theoretical Perspective], Ankara: Nobel Yayınevi, 2021.

Aydın, Mustafa, and Cihan Dizdaroğlu. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler: TRIP 2018 Sonuçları Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme [[International Relations in Turkey: An Assessment of the Results of the 2018 TRIP Survey].” Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 16, no. 64 (December 1, 2019): 3–28. https://doi.org/10.33458/uidergisi.652877.

Aydın, Mustafa, and Korhan Yazgan. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenleri Araştırma, Eğitim ve Disiplin Değerlendirmeleri Anketi-2009 [Survey Assessing Research, Education and Discipline of International Relations Academics in Turkey-2009].” Uluslararası İlişkiler 7, no. 25 (2010): 3–42.

Aydın, Mustafa, and Korhan Yazgan. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenleri Eğitim, Araştırma ve Uluslararası Politika Anketi-2011 [International Relations Scholars in Turkey Education, Research, and International Politics Survey-2011].” Uluslararası İlişkiler 9, no. 36 (2013): 3-44.

Aydın, Mustafa, Fulya Hisarlioğlu, and Korhan Yazgan. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenleri ve Alana Yönelik Yaklaşımları Üzerine Bir İnceleme: TRIP 2014 Sonuçları [An Investigation of International Relations Academics and their Approaches to the Field: TRIP 2014 Results].” Uluslararası İlişkiler 12, no. 48 (2016): 3–35.

Aydın, Mustafa. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Akademisyenlerinin Bilimsel Araştırma ve Uygulamaları ile Disipline Bakış Açıları ve Siyasi Tutumları Anketi [Survey of Turkish International Relations Scholars’ Scientific Research and Practices Based on their Disciplinary Perspectives and Political Dispositions].” Uluslararası İlişkiler 4, no. 15 (2007): 1–31.

Aydinli, Ersel. “Methodological Poverty and Disciplinary Underdevelopment in IR.” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 8, no. 2 (January 22, 2019): 109–15. http://dergipark.gov.tr/doi/10.20991/ allazimuth.513139.

Aydinli, Ersel. “Methodology as a Lingua Franca in International Relations: Peripheral Self-Reflections on Dialogue with the Core.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 13, no. 2 (June 1, 2020): 287–312.

Aydinli, Ersel. “Opening Speech.” In 2ndPolitics and International Relations Congress. Trabzon - Turkey: Karadeniz Technical University. 2018. Available from: https://youtu.be/xz-R7FUWzq0, (Retrieved: 30.10.2021).

Aydinli, Ersel, and Gonca Biltekin. “Time to Quantify Turkey’s Foreign Affairs: Setting Quality Standards for a Maturing International Relations Discipline.” International Studies Perspectives 18, no. 3 (2017): 267–87.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Julie Mathews. “Are the Core and Periphery Irreconcilable? The Curious World of Publishing in Contemporary International Relations.” International Studies Perspectives 1, no. 3 (December 2000): 289–303. https://academic.oup.com/isp/article-lookup/doi/10.1111/1528-3577.00028.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Julie Mathews. “Periphery Theorising for a Truly Internationalised Discipline: Spinning IR Theory out of Anatolia.” Review of International Studies 34, no. 4 (October 1, 2008a): 693–712.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Julie Mathews. “Turkey: Towards Homegrown Theorizing and Building a Disciplinary Community.” In International Relations Scholarship Around the World, edited by Arlene B. Tickner and Ole Wæver, 208-22. London: Routledge, 2009.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Julie Mathews. “Türkiye Uluslararası Ilişkiler Disiplininde Özgün Kuram Potansiyeli: Anadolu Ekolünü Oluşturmak Mümkün Mü [Homegrown Scholarship Potential of Turkish International Relations: Is it Possible to Create and Anatolian School?]?” Uluslararasi Iliskiler 5, no. 17 (2008): 161–87.

Baldwin, David A. “Interdependence and Power: A Conceptual Analysis,” International Organization 34, no. 4 (1980): 471–506.

Bilgin, Pinar, and Oktay F Tanrisever. “A Telling Story of IR in the Periphery: Telling Turkey about the World, Telling the World about Turkey.” Journal of International Relations and Development 12, no. 2 (June 11, 2009): 174–79. https://doi.org/10.1057/jird.2009.5.

Bilgin, Pınar. “Uluslararası İlişkiler Çalışmalarında ‘Merkez-Çevre’: Türkiye Nerede? [‘Center-Periphery’ in International Relations Studies: Where is Turkey?]” Uluslararası İlişkiler 2, no. 6 (2005): 3–14.

Dedeoğlu, Beril. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Çalışmaları ve Eğitimi Çalıştayı (16-17 Nisan 2005) Üzerine [On International Relations Research and Education in Turkey Workshop (16-17 April, 2005)].” Uluslararası İlişkiler 2, no. 6 (2005): 151–55.

Guzzini, Stefano. “The Concept of Power: A Constructivist Analysis,” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 33, no. 3 (2005): 495–521.

Hoffman, Stanley. “An American Social Science: International Relations.” Daedalus 106, no. 3 (1977): 41–60.

İşeri, Emre and Nevra Esentürk. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Çalışmaları: Merkez-Çevre Yaklaşımı [International Relations Studies in Turkey: Center-Periphery Perspective].” Elektronik Mesleki Gelişim ve Araştırma Dergisi 2016, no. 2 (2016): 17–33, www.ejoir.org.

Jackson, Patrick Thaddeus, The Conduct of Inquiry in International Relations: Philosophy of Science and Its Implications for the Study of World Politics. New York: Routledge, 2011.

Keyman, E. Fuat, and N Esra Ülkü. “Türkiye Üniversitelerinde Uluslararası İlişkiler Ders Müfredatı [International Relations Curriculum in Turkish Universities).” Uluslararası İlişkiler 4, no. 13 (2007): 99–106.

Kurubaş, Erol. “Türkiye Uluslararası İlişkiler Yazınında Tarihsel Olguculuk ile Disiplinlerarasıcılığın Analitik Yaklaşma Etkisi ve Türkiye Uygulaması [Impact of Historical-Factualism and Interdisciplinary Research on Conceptual Analyses in International Relations Literature in Turkey].” Uluslararası İlişkiler 5, no. 17 (2008): 129–59.

Mouton, Johann, and H. C. Marais, Basic Concepts in the Methodology of Social Sciences. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council, 1996.

Özcan, Gencer. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Alanında Lisansüstü Eğitimin Sorunları [Problems of Undergraduate Education in the Field of International Relations in Turkey].” Uluslararası İlişkiler 4, no. 13 (2007): 107–112.

Sartori, Giovanni, ed. Social Science Concepts: A Systematic Analysis. Beverley Hills: Sage, 1984.

Sarı, Buğra and İsmail Erkam Sula. Kuramsal Perspektiften Temel Uluslararası İlişkiler Kavramları [Basic International Relations Concepts from Theoretical Perspective], 2021. Ankara: Nobel Yayınevi.

Sula, Ismail Erkam. “Güvenlikleştirme Kuramında ‘Söz Edim’ ve ‘Pratikler’: Türkçe Güvenlikleştirme Yazınında ‘Yöntem’ Arayışı [‘Speech Acts’ and ‘Practices’ in Securitization Studies: A Search for ‘Methods’ in Turkish Securitization Literature].” Güvenlik Stratejileri Dergisi 17, no. 37 (March 30, 2021): 85–118. https://doi. org/10.17752/guvenlikstrtj.905758.

Sula, Ismail Erkam. “‘Global’ IR and Self-Reflections in Turkey: Methodology, Data Collection, and the Social Sciences Data Repository.” All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace 11, no. 1 (2022): 123-142. https://doi. org/10.20991/allazimuth.1032115.

Şule Kut, Ali Karaosmanoğlu, and Atila Eralp. “Workshop Report International Relations Studies and Education in Turkey.” Uluslararası İlişkiler 2, no. 6 (2005): 131–47.

Yalçınkaya, Alaeddin and Ertan Efegil. “Türkiye’de Uluslararası İlişkiler Eğitiminde ve Araştırmalarında Teorik ve Kavramsal Yaklaşım Temelinde Yabancılaşma Sorunu [The Problem of Theoretical and Conceptual Alienation of International Relations Education in Turkey].” Gazi Akademik Bakış 3, no. 5 (2009): 207–30.