Steve Shellman and Sean O’Brien

Strategic Analysis Enterprises (SAE), Inc.

Automated event data extraction techniques have revolutionized the study of conflict dynamics through the ability of these techniques to generate large volumes of timely data measuring dynamic interactions among actors around the world. In this paper, we describe our approach for adapting these techniques to extract data on sentiments and emotions, which are theorized to crucially contribute to escalating and de-escalating conflict. Political scientists view political conflict as resulting from a series of strategic interactions between groups and individuals. Psychologists highlight additional factors in political conflict, such as endorsements and condemnations, the public’s attitude toward its leaders, the impact of public attitudes on policy, and decisions to engage in armed conflict. This project combines these two approaches to examine hypotheses regarding the effects that different emotional impulses have on government and dissident decisions to escalate or de-escalate their use of hostility and violence. Across the two cases examined—the democratic Philippines and authoritative Egypt between 2001 and 2012—we found consistent evidence that intense societal fear of dissidents and societal disgust toward the government were associated with increases in dissident hostility. Conversely, societal anger toward dissidents was associated with a reduction in dissident hostility. However, we also found noticeable differences between the two regimes. We close the article with a summary of these similarities and differences, along with an assessment of their implications for future conflict studies.

An Empirical Assessment of the Role of Emotions and Behavior in Conflict Using Automatically Generated Data[1]This study was primarily funded by the US Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL). The data collected were jointly funded by the US National Science Foundation (NSF: BCS-0904921; SES-0516545) and the US Navy’s Office of Naval Research (N00014- 10-C-0338). We would like to thank Laurie Fenstermacher at AFRL for supporting our research efforts and for her comments, criticisms, and suggestions. We would also like to thank Hans Leonard, Marcia Zangrilli, and Michael Covington for their research assistance.

1. Introduction

A major hypothesis emerging from the social psychology literature is that individuals’ choices are strongly influenced by their own and others’ emotions. While experiments to that end have been conducted in labs around the world, there is a lack of empirical analyses focusing on how key actors involved in political crises react in response to different emotional impulses emanating from different types of actors. The research to date on how emotions impact conflict behavior has been largely descriptive in nature, lacking scientific rigor and unbiased empirical assessments. The primary purpose of this article is to describe our approach for breaking new ground in the study of emotions and their impacts on the strategic and tactical choices of individuals, groups, and governments while engaged in domestic and/or international political struggles. Our project uses new, innovative, and near-real-time automated tools to extract and measure expressions of emotion from text samples and assess how such emotions influence the behavior of governments and dissidents. Similar events in different countries or contexts can produce distinct emotional impulses, and knowing how leaders and mass movements are likely to react to these impulses is crucial to our ability to anticipate crises and their trajectories, such as those that have occurred most recently in the Middle East.

Much of the social-psychology literature focuses on how emotions influence one’s behavior.[2] Icek Ajzen, Attitudes, Personality, and Behavior (Chicago: Dorsey Press, 1988); Catherine A. Cottrell and Steven L. Neuberg, “Different Emotional Reactions to Different Groups: a Sociofunctional Threat-based Approach to “Prejudice”,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 88 (5) (2005): 770-789. In this article, we examine this relationship from a different perspective by developing and testing hypotheses on how societal emotions affect government leaders’ behavioral responses toward their opponents and constituencies. The effects of revolutionaries such as Mao Zedong and Che Guevara, along with US counter-insurgency doctrine, suggest that societal attitudes can have a decisive impact on the outcomes of conflict and irregular warfare.[3] David H. Petraeus and James F. Amos, U.S. Army/U. S. Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007).The victor in these often-protracted engagements usually holds the support of the population. Popular support is often conceptualized in terms of the extent to which one favors, likes, or trusts a person or policy position. Yet, some leaders gain support through coercion. For example, groups may violently attack civilians to spread fear and panic within a wider audience to compel people to support their cause. Others, such as Hezbollah, provide social services to win over potential supporters. Governments and dissidents generally gauge public attitudes before taking action and then conduct themselves in ways that increase support— either through fear or trust. In this paper, we focus on the anger and disgust associated with unsupportive attitudes, as such expressions can also impact an actor’s decisions. In short, we ask: How do societal emotions such as anger, disgust, fear, and trust influence government and dissident behavior?

Using automated natural language processing (NLP) techniques, we collected data on what citizens, dissidents, and governments were doing to (events data) and saying (sentiment/ emotions data) about each other in the Philippines and Egypt over the period 2001 to 2012. We disaggregated the emotions and sentiment data of those three actor types, and evaluated several hypotheses linking emotions to the others’ behavioral responses in the context of conflict and hostility.

In the first section of this paper, we articulate our conception of conflict as a series of strategic interactions between dissidents, governments, and the citizens whose allegiance they compete for. Next, we discuss the evolution of automated techniques to extract dynamic behavioral data from unstructured text. We introduce our approaches for automatically extracting dynamic events, sentiment expressions, and emotional responses between the key societal actors. Following our analyses of the data generated by these techniques in the context of Egypt and the Philippines, we close the article with a summary of our results and their policy implications.

2. Conceptualization of Conflict

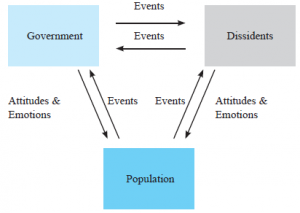

Political conflict can be viewed as resulting from a series of strategic interactions between groups and individuals.[4] David H. Lake and Robert Powell, "International Relations: A Strategic-Choice Approach," in Strategic Choice and International Relations, eds. David H. Lake and Robert Powell (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999); Stephen M. Shellman, Clare J. Hatfield, and Maggie J. Mills, "Disaggregating Actors in Intrastate Conflict," Journal of Peace Research 47 (1) (2010): 83-90; Stephen M. Shellman, Taking Turns: A Theory and Model of Government-Dissident Interactions (Saarbrucken: VDM Verlag, 2010); Stephen M. Shellman, “Leaders and Their Motivations: Explaining Government-Dissident Conflict-Cooperation Processes,” Conflict Management & Peace Science 23 (1) (2006a): 73-90; Stephen M. Shellman, “Process Matters: Conflict and Cooperation in Sequential Government-Dissident Interactions,” Security Studies 15 (4) (2006b): 563-599.Conflict is not an illness a society “catches” like a seasonal cold; rather, it is a process whereby competing actors make interdependent strategic decisions that serve to escalate and de-escalate conflict. This process, which we depict in Figure 1, is characterized by a series of cost and benefit calculations. Political leaders, for instance, seek to obtain (or retain) political office so that they may allocate resources in accordance with their policy positions. Dissident leaders, much as their government opponents, seek to retain power in their organizations and control over their subordinates. Government and dissident leaders are constrained, enabled, or threatened by their internal and external coalitions, who judge their leaders’ performances by examining their interactions with their opponents and the resulting outcomes. Thus, monitoring changes in popular support, sentiment, rhetoric, and emotions becomes an important tool for maintaining power and influence.

Audience costs affect leaders’ tenure in office. These costs come in many forms, such as through losing elections and influence, assassinations, splits between dissident organizations and factions, and coups d’états. Shellman argues that leaders must minimize these costs by reducing hostility from their opponents and by instilling positive attitudes and emotions among their supporters.[5] Shellman, “Leaders and Their Motivations”; Shellman, “Process Matters”; Shellman, Taking Turns. Leaders are also constrained by regime type. Autocratic leaders instill fear in the population and repress them into submission. Democratic leaders, by contrast, must obey the rule of law, and fear being ousted by the public, whether through popular election or other means, such as a military coup or rebellion.

3. The Evolution of Behavioral Conflict Data

While the conceptualization of conflict as a process has been theorized in academic literature for decades, until recently, efforts to test and evaluate hypotheses derived from these theoretical arguments have been hampered by a lack of available data to operationalize these key concepts. The ‘behavioral revolution’ in political science in the late 1960s led to the development of numerous conflict datasets, including the Correlates of War (COW) Project,[6] J. David Singer and Melvin Small, The Wages of War, 1816-1965: A Statistical Handbook (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1972).the International Crisis Behavior (ICB) Project,[7] Jonathan Wilkenfeld, Michael Brecher, and Sheila Moser, Crises in the Twentieth Century: Handbook of Foreign Policy Crises (Oxford, England: Pergamon Press, 1988).and the Uppsala Conflict Data Program,[8] Peter Wallensteen and Margareta Sollenberg, “Armed Conflict 1989-98,” Journal of Peace Research 36 (5) (1999): 593-606.among many others. Although embracing different definitions of conflict to suit the research interests of the principal investigators, these projects were united by their common goal of tracking the occurrence of conflict (primarily at the nation-state level) and its characteristics (e.g., battle deaths, distance between opponents, regime type, size of military forces).

For decades, these datasets served as the gold standard in quantitative analyses by which to identify the key correlates of conflict, which were almost exclusively performed using country-year as the unit of observation. By the late 1990s and early 2000s, several groups of scholars and government analysts[9]Daniel C. Esty et al, Working Papers: State Failure Task Force Report (McLean, VA: Science Applications International Corporation, 1995), accessed June 8, 2009, http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p312200_index.html; Daniel C. Esty et. al., The State Failure Task Force Report: Phase II Findings (McLean, VA: Science Applications International Corporation, 1998), accessed June 8, 2009, http://globalpolicy.gmu.edu/pitf/SFTF%20Phase%20II%20Report.pdf; Sean P. O’Brien, “Anticipating the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: An Early Warning Approach to Conflict and Instability Analysis,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 46 (2002): 791-811. were employing these datasets to generate fairly reliable forecasts of countries most likely to experience conflict and instability given their macro- structural conditions (e.g., regime type, demographic trends, level of commitment to political rights, human rights). Although these studies were impressive in the accuracy with which they could forecast nation-state risks for conflict (around 80% accuracy over five years), they suffered from two main limitations.

First, these macro-structural risk assessments were generated without taking into account how interactions between individuals and groups might influence the character and timing of conflict. They were instead concerned with identifying the conditions that make countries more or less susceptible to conflict. Although these conditions do indeed enable or constrain leaders and dissidents, they do not inform us about the behaviors these actors might exhibit under different circumstances, specifically in response to actions undertaken by their opponents. As a result, although macro-structural forecasts provide useful early warnings of nation-state conflict risks, they mask the mechanisms by which these conflicts can occur. Second, most of the key variables examined as potential correlates or drivers of conflict were measured annually, so forecasts over more-specific time frames (weeks or months) were impossible.

3.1. The development of automated data extraction techniques

The above problems were mitigated with the development of techniques to automatically extract and code dynamic event interactions from news reports. Phil Schrodt’s Kansas Event Data System (KEDS) was the first major project to demonstrate that NLP techniques could be used to generate daily measures of a wide array of conflictual and cooperative interactions between individuals and organizations, with accuracy equivalent to human annotators.[10] Philip A. Schrodt, Shannon G. Davis, and Judith L. Weddle, “Political Science: KEDS—A Program for Machine Coding Events Data,'' Social Science Computer Review 12 (3) (1994): 561-88; Philip A. Schrodt and Deborah J. Gerner, “Empirical Indicators of Crisis Phase in the Middle East, 1979–1995,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 41 (1997): 529-552.With automated coding, the coding rules are transparent, the data are easily and quickly reproducible, and the data can be regenerated using alternative coding schemes. This development has radically changed the information that is now available to researchers and analysts. The KEDS project has spawned a number of similar projects, and this technology has spilled over into a variety of other areas of political science.

The Kansas Event Data System and its open-source successor, the Text Analysis by Augmented Replacement Instructions (TABARI) program, utilizing the Conflict and Mediation Event Observations (CAMEO) system, were originally used to collect information primarily on regional interactions among actors (primarily in the Levant). Although most event datasets were generated by coding state-to-state interactions, a major breakthrough in the coding of sub-state actors originated with the Protocol for the Analysis of Nonviolent Direct Action (PANDA) project in the early 1990s. In addition to coding sub-state actors, PANDA’s focus was on acts of non-violence and low-level contentious politics. That actor system was then incorporated into Bond et al.’s Integrated Data for Event Analysis (IDEA) system, which performs global coding.[11] Doug Bond, Craig Jenkins, and Kurt Schock, “Mapping Mass Political Conflict and Civil Society: Issues and Prospects for the Automated Development of Event Data,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 41 (1997): 553-579.Some of the IDEA data are available publicly but much remain proprietary.

Building on these projects, we developed our own suite of NLPtechniques to automatically code dynamic behavioral indicators from text, which we refer to as Xenophon. Xenophon uses the same basic structure as TABARI/CAMEO, but the primary difference is that we take sentence structure (using a tagger and parser) into account, which allows us to better disambiguate the sources and targets of particular events. We also utilize a more extensive set of actor dictionaries relative to most of the previous work in this area, which allows us to make finer distinctions and disaggregate actions among individuals, groups, governments, and organizations.

3.2. Extending events data extraction for coding sentiments and emotions

With the ability to automatically extract dynamic events in near real time, we can create customizable behavioral indices, such as measures of protest, dissent, and violence. This feature enables us to examine hypotheses consistent with our theory of conflict, that is, as resulting from a series of strategic calculations between dissidents and government actors. However, as our theory postulates that these actors compete for winning people’s hearts and minds, we needed measures of societal support for them. Moreover, to test some of our psychological hypotheses about how different behavior is driven by discrete emotions, we needed a way to capture different emotional expressions.

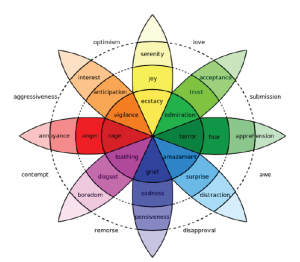

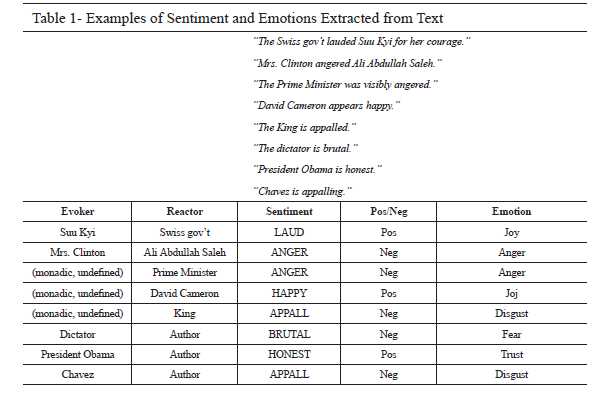

For the above reasons, we adapted our events-data framework to capture sentiment expressions and emotional responses by adjusting our techniques in two crucial areas. First, we replaced the verb or event taxonomy in our coding engine with a comprehensive taxonomy of sentiment words and phrases. This taxonomy includes variations of the most-common sentiment expressions used in politically relevant discourse and that span the range of attitudes from distain to admiration. From these main expressions, we derived 1,464 different patterns of the way in which sentiments are expressed in common discourse. Second, we attached an emotion to each sentiment expression, based on Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions, displayed in Figure 2. [12]Robert Plutchik, Emotion, a Psychoevolutionary Synthesis (New York: Harper and Row, 1980).

Plutchik postulated the existence of eight primary, discrete emotions: joy versus sadness; anger versus fear; trust versus disgust; and surprise versus anticipation. He uses the concept of a wheel to illustrate that these emotions can be expressed in different mixes and intensities. Table 1 provides some examples of how our Pathos sentiment engine transforms text from blogs or news reports into raw data measuring different sentiments and emotions.

In coding sentiment and emotional expressions, we have replaced the notion of sources and targets, commonly used in most event extraction frameworks, with more appropriate references to evokers and reactors. We also have placeholders for monadic sentiment expressions, which occur when an unidentified actor (such as the author of a blog posting) expresses a particular sentiment, or in cases where the object of one’s sentiment is undefined. For example, in the statement “The president was angry when he left,” we do not know with whom or about what issue the president was angry. With the adaptation of our automated events data extraction techniques for coding multi-adic expressions of sentiment and emotions, we now have the tools to collect the data necessary to evaluate hypotheses concerning the impact of emotions and attitudes on government and dissident behavior in the context of conflict and hostility.

4. Hypotheses

Emotions are critical to the natural goal-seeking process because they signal circumstances that threaten or further one’s goals. Emotions direct and energize behavior toward remediating threats or exploiting benefits.[13] Cottrell and Neuberg, “Different Emotional Reactions.”Emotions are also linked to habitual behavioral patterns; understanding the effects of emotions can prove useful for identifying and predicting how individuals will respond to various emotional stimuli. Kuppens et al. hypothesize that different events evoke different emotions and that different emotions provoke different actions. Fearful people tend to avoid conflict while angry people tend to take action.[14] Peter Kuppens et al., “The Appraisal Basis of Anger: Specificity, Necessity and Sufficiency of Components,” Emotion 3 (3) (2003): 254-269. Matsumoto et al. argue that ‘disgust’ is the emotion that stems from ‘repulsion’ and tends to increase the desire to ‘eliminate’ the opposition.[15] David Matsumoto, Hyisung C. Hwang, and Mark G. Frank, “Emotional Language and Political Aggression,” Journal of Language and Social Psychology XX (X) (2013): 1-17, accessed May 8, 2013, DOI: 10.1177/0261927X12474654.This theory suggests the following testable hypotheses:

H1: If dissidents are feared by the population, dissidents will continue their violent actions

to perpetuate fear in the population (so that the population avoids conflict with them).

H 2: If people are angry at dissidents, dissidents will alter their behavior (e.g., lessen violent activities) to prevent actions by the general population that may be inconsistent with the dissidents’ objectives.

Autocratic governments may react in similar ways. Fearful people mean submissive people. Angry people present potential threats to leaders. Machiavelli argues that it is better to be feared than loved. Thus,

H3: Autocratic leaders will increase violence in the face of fear and decrease violence in the face of anger.

Democratic leaders, on the contrary, can be removed from office by fearful populations through elections, a feature of democracy that does not require large-scale collective action nor the necessity of publicly declaring or denouncing support for a person or policy. As such,

H4: Democratic leaders will lessen violence when confronted by fearful populations.

Democratic leaders should respond similarly to angry and disgusted populations. Their tenure is more susceptible to people’s negative emotions, and power is easier to lose when the masses revoke support. Governments and dissidents are also cognizant of how different groups within the population feel about each other and can react to such information. Thus, we might expect to observe the following:

H5: If dissidents know people are angry, fearful, or disgusted with the government, they will continue to increase their violent activities to attempt to take over the state.

H6: If democratic governments know people are angry, fearful, or disgusted with dissidents, they will increase their violent activities toward the dissidents to eliminate them.

H7: If autocratic repressive leaders know that society is angry, fearful, or disgusted with dissidents, they will lessen their own repressive activities against society so as to garner or retain societal support for the government.

There is no need to use repression when faced with unsupported dissidents; the dissidents will fizzle out without support from the masses.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, governments and dissidents may try to build trust within a population as a way of gaining support. If there are high levels of trust between the government and society, the likelihood of the government using violence against the population should be low. Similarly, dissidents will use less violence during periods of high trust between the population and the dissidents.

H8: As trust increases between the population and the government, or between the population and the dissidents, government and dissident violence alike should decrease.

5. Methodology

We examined these hypotheses using events data and emotions data collected for the Philippines and Egypt over the period 2001 to 2012. The events data came from a large Factiva corpus and the sentiment and emotions data came from Filipino and Egyptian bloggers identified on the World Wide Web. Because the Philippines is a democracy, and Egypt an authoritarian regime over our time period of analysis, we can examine the extent to which relationships between emotions and behavior operate differently in different regime types. We used our Xenophon events data extraction system to generate measures of hostility employed by government actors and dissidents. To do so we summed the negatively signed CAMEO event codes associated with government and dissident actions [16]Most dissident activity in the Philippines has been conducted by the Abu Sayyaf Group, Moro Islamic Liberation Organization, and Moro National Liberation Front. In Egypt, dissident organizations include the April 6 Youth Movement, Popular Committee for Supporting the Palestinians, Coalition of the Youth of the Revolution, Vanguards of Conquest, National Association for Change, Muslim Brotherhood, Revolutionary Socialists, and Intifada Solidarity Movement. to create a weighted hostility indicator. We used our Pathos system to extract measures of sentiment and emotions directed by societal actors toward dissidents and governments. Data on emotions were derived from the extracted sentiment expressions by assigning each sentiment word or phrase to a discrete category on Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions.[17] Plutchik, Emotion.

Our goal was to examine the nature of these relationships over time. The time series exhibited a non-constant variance across the time period. Therefore, we estimated the relationships using Auto Regressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (ARCH) models, which include a set of techniques well-suited for analyzing time-series data where the conditional variance changes over time.

6. Analysis and Results

We report the results for the Philippines and Egypt below. Note that the hostility variable is negatively signed, as are as the ‘negative emotions’ variables (fear, disgust, and anger). As such, positive and negative signs must be interpreted with care. Positive coefficients on negative emotions variables and hostility variables are associated with increases of violence, while negatively signed coefficients are associated with decreases in violence. Positive coefficients on positive emotions such as trust yield decreases in violence, while negatively signed coefficients indicate that trust increases violence.

We model government and dissident hostility levels. In addition to examining the impacts of emotions on behavior, our models control for the opponent’s behavior (i.e., dissident behavior for governments and government behavior for dissidents). A recurring finding in the literature is that the relationship between repression and dissent is nonlinear. Specifically, empirical studies find that dissent is highest when repression exists at moderate levels.[18] Stephen M. Shellman, Brian P. Levey, and Joseph K. Young, “Shifting Sands: Explaining and Predicting Phase Shifts by Dissident Organizations,” Journal of Peace Research 50 (3) (2013): 319-336, DOI: 10.1177/0022343312474013.In the absence of repression, there is little justification to rebel. By contrast, when repression is high, the costs of rebellion may exceed the potential gains. To test this hypothesis we add a variable that squares government hostility in our models of dissident hostility. We find support for this hypothesis across Egypt and the Philippines in that the non-squared term and the squared term are statistically significant and oppositely signed in both dissident hostility models. Plotting the model-predicted values corroborates an inverted-U relationship between government repression and dissident hostility levels. Below, we discuss the emotions variables and their effects on government and dissident hostility levels across Egypt and the Philippines.

6.1. Egypt

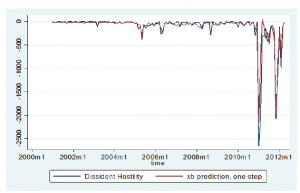

Figure 3 depicts the extent to which our model is useful in explaining levels of dissident hostility directed at both the government and society. The model-predicted values of hostility correlate with actual values at .93, indicating that we have an excellent model of dissident hostility. Our model of government hostility (not shown) exhibits a similar level of performance.

Table 2 displays the results of our time series estimating the effects of expressed emotions by societal actors toward government and dissident actors on dissident hostility in Egypt.

Table 2- Effects of Expressions of Emotions on Levels of Dissident Hostility in Egypt, 2001-2012

| Dissident Hostility | Coefficient | Robust SE z | pr(z) | |

| Gov to Dis Hostility | 0.4489497 | 0.0437715 | 10.26 | 0 |

| Gov to Dis Hostility 2 | -0.000505 | 0.0000274 | -18.42 | 0 |

| Society to Dissident Anger | -1.638102 | 0.6779109 | -2.42 | 0.016 |

| Society to Dissident Fear | 28.36196 | 2.450034 | 11.58 | 0 |

| Society to Dissident Trust | 0.0001268 | 1.578252 | 0 | 1 |

| Society to Dissident Disgust | -0.6539234 | 0.5264639 | -1.24 | 0.214 |

| Society to Government Anger | 1.00773 | 0.268879 | 3.75 | 0 |

| Society to Government Fear | -0.2789526 | 0.7501911 | -0.37 | 0.71 |

| Society to Government Trust | 2.208435 | 0.5360677 | 4.12 | 0 |

| Society to Government Disgust | 6.968489 | 0.9480729 | 7.35 | 0 |

| Cons | -13.4036 | 3.651676 | -3.67 | 0 |

| MA | -0.1316956 | 0.0169177 | -7.78 | 0 |

| ARCH | 4.154678 | 2.486187 | 1.67 | 0.095 |

| Note substantive effects shown below | ||||

Consistent with H2, dissident hostility declines as societal anger toward dissidents increases. Consistent with H1, we observe a very strong, positive relationship between societal fear of dissidents and dissident hostility, indicating that as fear increases so does violence. We also find support, consistent with H5, for the notion that dissidents respond to societal disgust toward their government with greater levels of hostility. Dissident violence against government institutions and symbols demonstrates that dissidents are equally disgusted with the government, and willing to take actions to overthrow the regime. Finally, consistent with H8, we observe that increased societal trust toward the government is associated with decreases in dissident violence. The coefficient on societal trust toward dissidents was also positive, yet it was not statistically significant. Taken together, these findings suggest that dissidents will exploit the emotions of fear and disgust in their effort to undermine government authority and people’s faith in the government’s ability to protect them from dissident actions, all of which furthers their aims.

Tabble 3 shows the results of the analyses to assess the impact of different societal emotions on levels of government hostility in Egypt. We find strong support for the notion that this autocratic government lessened its hostility toward dissidents in response to societal expressions of fear of dissidents, and somewhat less support for the notion that societal anger toward dissidents also reduces government hostility toward dissidents. These results are consistent with H7. However, there is a difference with respect to disgust. When society expressed disgust for the government, the latter lashed out with greater levels of hostility in an attempt to bring about greater submissiveness. This reaction is inconsistent with H7. When Egypt’s population indicated trust in both the government and dissidents, the government reduced its displays of hostility toward dissidents. These findings are consistent with H8.

Table 3- Effects of Expressions of Emotions on Levels of Government Hostility in Egypt, 2001-2012

| Gov to Dissident Hostility | coefficient | Robust SE | z | pr(z) |

| Dissident hostility | 0,679991 | 0,012812 | 53,08 | 0 |

| Society to Dissident Anger | -4,25168 | 0,693646 | -6,13 | 0 |

| Society to Dissident Fear | -38,5291 | 9,414314 | -4,09 | 0 |

| Society to Dissident Trust | 2,108596 | 0,892052 | 2,36 | 0,018 |

| Society to Dissident Disgust | -4,12852 | 2,003278 | -2,06 | 0,039 |

| Society to Government Anger | -0,3902 | 0,733479 | -0,53 | 0,595 |

| Society to Government Fear | -0,38079 | 2,106473 | -0,18 | 0,857 |

| Society to Government Trust | 6,023762 | 2,206856 | 2,73 | 0,006 |

| Society to Government Disgust | 12,49639 | 1,989252 | 6,28 | 0 |

| _cons | -22,712 | 7,342872 | -3,09 | 0,002 |

| MA | 0,469103 | 0,075811 | 6,19 | 0 |

| ARCH | 0,989996 | 0,276628 | 3,58 | 0 |

6.2 The Philippines

To assess the extent to which regime type might alter our findings for government behavior as indicated by our hypotheses, we replicated the models for the Philippines over the period 2001 to 2012. Figure 4 shows our model’s predicted values of Philippine dissident hostility versus actual values of Philippine dissident hostility. Although the model fit is somewhat weaker than that observed in Egypt (r=.80 vs. 93, respectively), it still suggests we have a good model of dissident hostility in the Philippines. The government hostility model-predicted values (not shown here) correlate with actual government hostility at .83, indicating a well- performing model of government hostility as well.

Table 4 displays effects for government hostility in the Philippines that are quite different from what was observed in Egypt (compare results to Table 3). As societal anger toward dissidents increased over the sample period, the Philippine government appeared to use that anger as a pretext for cracking down on dissidents through displays of increasing hostility toward them. Furthermore, when Philippine society displayed higher levels of fear and disgust toward the government, it responded by reducing its level of hostility. Because Egypt was an authoritarian regime through much of the analysis time frame, and the Philippines a democracy, these results suggest the value that democratic governments place on not alienating their people, even in the midst of a battle against violent opposition to their authority.

Table 4- Effects of Expressions of Emotions on Levels of Government Hostility in the Philippines, 2001-2012

| Gov to Dissident Hostility | coefficient | Robust SE | z | pr(z) |

| Dissident hostility | 0,502222 | 0,043315 | 11,59 | 0 |

| Society to Dissident Anger | 6,559452 | 1,40939 | 4,65 | 0 |

| Society to Dissident Fear | 1,82246 | 4,012846 | 0,45 | 0,65 |

| Society to Dissident Trust | -1,16605 | 2,343723 | -0,5 | 0,619 |

| Society to Dissident Disgust | Dropped | |||

| Society to Government Anger | -0,24874 | 0,68927 | -0,36 | 0,718 |

| Society to Government Fear | -6,94073 | 3,385746 | -2,05 | 0,04 |

| Society to Government Trust | -0,56976 | 0,899129 | -0,63 | 0,526 |

| Society to Government Disgust | -4,76318 | 3,139302 | -1,52 | 0,129 |

| _cons | -44,3678 | 13,74301 | -3,23 | 0,001 |

| MA | 0,157884 | 0,058751 | 2,69 | 0,007 |

| ARCH | -0,06068 | 0,019207 | -3,16 | 0,002 |

Table 5 displays the results of the analysis to assess the impact of different emotions on Philippine dissidents’ behavior. The results are markedly consistent with those found in Egypt. Intense societal fear of dissidents generated the largest statistically significant increases in dissident hostility (H1). By contrast, societal anger toward dissidents is followed by significant reductions in dissident hostility (H2). We further find support for H5, specifically, that dissidents exploit increases in societal fear of government actions by displaying higher levels of hostility toward the government.

Table 5-Effects of Expressions of Emotions on Levels of Dissident Hostility in the Philippines, 2001-2012

| Dissident Hostility | coefficient | Robust SE | z | pr(z) |

| Gov to Dis Hostility | 0,52881 | 0,162628 | 3,25 | 0,001 |

| Gov to Dis Hostility 2 | -0,00071 | 0,000225 | -3,15 | 0,002 |

| Society to Dissident Anger | -4,3229 | 2,342181 | -1,85 | 0,065 |

| Society to Dissident Fear | 28,49071 | 10,04412 | 2,84 | 0,005 |

| Society to Dissident Trust | -5,06235 | 3,712736 | -1,36 | 0,173 |

| Society to Dissident Disgust | Dropped | |||

| Society to Government Anger | 0,00629 | 0,700256 | 0,01 | 0,993 |

| Society to Government Fear | 11,86902 | 4,2934 | 2,76 | 0,006 |

| Society to Government Trust | -0,78618 | 1,096972 | -0,72 | 0,474 |

| Society to Government Disgust | 7,303007 | 6,225772 | 1,17 | 0,241 |

| _cons | -123,235 | 21,37083 | -5,77 | 0 |

| MA | 0,619732 | 0,069555 | 8,91 | 0 |

| ARCH | 1,137012 | 0,563449 | 2,02 | 0,044 |

In Figure 5, we display the substantive effects computed for societal fear and anger directed toward dissidents on dissident hostility in Egypt and the Philippines. The results suggest very consistent impacts, giving us greater confidence in the possible generalizability of these results to other cases. In the Philippines, as societal expressions of fear toward dissidents moves from 0 to -20 (the maximum), dissident hostility increases by more than 700 on a scale of -1698 to 0, with a mean of -206 and a standard deviation of 239. That result is more than two standard deviations above the mean. Similarly, in Egypt, as societal expressions of fear toward dissidents move from 0 to -15 (the maximum), dissident hostility increases by almost 500 on a scale of -2700 to 0, with a mean of -118 and a standard deviation of 354. That result is more than one standard deviation above the mean change. The figures also show similarities with respect to slight decreases in dissident violence that result from increases in societal anger.

6.3. Endogenous relationships

It could be the case that fear is not perpetuating hostility but that hostility is perpetuating fear. Much the same could be said for anger and disgust and how they are evoked by different types of behaviors. As part of a US Air Force Research Lab project, we tested for reverse causation and found that neither government nor dissident hostility levels influenced societal expressions of fear, disgust, or trust. However, expressions of anger were influenced by hostility levels. Perhaps we need to disaggregate hostility into violent tactics and nonviolent tactics, and further divide violent tactics into attacks on civilians and attacks on state authorities. More- nuanced measures might better explain the variation in emotionally charged sentiments. That said, knowing that the aggregate variables do not exhibit endogenous correlations within time-series statistical models lends additional credence to our uni-directional study and findings.

7. Summary and Conclusions

Political scientists view political conflict as resulting from a series of strategic interactions between groups and individuals. Psychologists highlight different factors in political conflicts, such as endorsements and condemnations, the public’s attitude toward its leaders, the conflict’s impact on policy, and decisions to engage in armed conflict. This project combines these two approaches to examine hypotheses relating to the effects that different emotional impulses have on government and dissident decisions to escalate or de-escalate their use of hostility and violence. Across the two different cases examined—the democratic Philippines and authoritative Egypt—we found consistent evidence that intense societal fear of dissidents and societal disgust toward the government were associated with increases in dissident hostility. Conversely, societal anger toward dissidents was associated with a reduction in dissident hostility.

However, there were noticeable differences between the two regimes. The democratic Philippines appears to view negative social attitudes toward dissidents, principally anger, as a pretext to justify cracking down on dissidents through escalating repression. It eased up on its repression in such cases where society began to fear the government or display disgust toward it. A democratic government’s reflexive recoil from societal anger and disgust makes sense to the extent that democratic leaders require the support of the people to attain or retain political office. Conversely, the authoritative Egyptian government reacted to similar forms of disgust by intensifying its repression of society, displaying a need to achieve population submission lest the people rise up in opposition.

The results reported in this article, while tempered by the limited set of cases examined, suggest the importance of continued efforts to uncover the mechanisms by which governments and opposition movements generate various emotional impulses, and, in turn, how these emotions affect the decision calculus of their opponents. The data discussed here could be further disaggregated to examine particular groups in the Philippines, such as the Abu Sayyaf, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, and the New People’s Army. One could also explore how emotions affect levels of cooperation among a wider variety of actors. One could further investigate endogenous relationships, such as the influence that behavior has on societal emotions. Shedding additional light on these relationships, and the contexts and boundary conditions (i.e., regime type) under which they apply, would help the research community better anticipate how these factors can serve to escalate or de-escalate violence and hostility.

Ajzen, Icek. Attitudes, Personality, and Behavior. Chicago: Dorsey Press, 1988.

Bond, Doug, Craig Jenkins, and Kurt Schock. “Mapping Mass Political Conflict and Civil Society: Issues and Prospects for the Automated Development of Event Data.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 41 (1997): 553-579.

Cottrell, Catherine A. and Steven L. Neuberg. “Different Emotional Reactions to Different Groups: a Sociofunctional Threat-based Approach to “Prejudice”.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 88 (5) (2005): 770-789.

Ekman, P. “An Argument for Basic Emotions.” Cognition and Emotion 6 (3-4) (1992): 169-200.

Esty, Daniel C., Jack Goldstone, Ted Robert Gurr, Pamela Surko, and Alan N. Unger. Working Papers: State Failure Task Force Report. McLean, VA: Science Applications International Corporation, 1995. Accessed June 8, 2009. http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p312200_index.html.

Esty, Daniel C., Jack Goldstone, Ted Robert Gurr, Barbara Harff, Marc Levy, Geoffrey D. Dabelko, Pamela T. Surko, and Alan N. Unger. The State Failure Task Force Report: Phase II Findings. McLean, VA: Science Applications International Corporation, 1998. Accessed June 8, 2009. http://globalpolicy.gmu.edu/pitf/SFTF%20Phase%20 II%20Report.pdf.

Kuppens, Peter, Iven Van Mechelen, Dirk J.M. Smits, Paul De Boeck. “The Appraisal Basis of Anger: Specificity, Necessity and Sufficiency of Components.” Emotion 3 (3) (2003): 254-269.

Lake, David H. and Powell, Robert. “International Relations: A Strategic-Choice Approach.” In Strategic Choice and International Relations, edited by David H. Lake and Robert Powell. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999.

Lerner, Jennifer S. and Keltner, Dacher. “Fear, Anger, and Risk.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81(1) (2001): 146-159.

Matsumoto, David, Hyisung C. Hwang and Mark G. Frank. “Emotional Language and Political Aggression.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology XX (X) (2013):1-17. Accessed May 8, 2013. DOI: 10.1177/0261927X12474654

O’Brien, Sean P. “Anticipating the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: An Early Warning Approach to Conflict and Instability Analysis.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 46 (2002): 791-811.

Petraeus, David H., and James F. Amos. U.S. Army/U. S. Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

Plutchik, Robert. Emotion, a Psychoevolutionary Synthesis. New York: Harper and Row, 1980.

Schrodt, Philip A., and Deborah J. Gerner. “Empirical Indicators of Crisis Phase in the Middle East, 1979–1995.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 41 (1997): 529-552.

Schrodt, Philip A., Shannon G. Davis, and Judith L. Weddle. “Political Science: KEDS―A Program for Machine Coding Events Data.’’ Social Science Computer Review 12 (3) (1994): 561-88.

Shellman, Stephen M. “Leaders and Their Motivations: Explaining Government-Dissident Conflict-Cooperation Processes.” Conflict Management & Peace Science 23 (1) (2006a): 73-90.

Shellman, Stephen M. “Process Matters: Conflict and Cooperation in Sequential Government-Dissident Interactions.” Security Studies 15 (4) (2006b): 563-599.

Shellman, Stephen M. Taking Turns: A Theory and Model of Government-Dissident Interactions. Saarbrucken: VDM Verlag, 2010.

Shellman, Stephen M., Clare J. Hatfield, and Maggie J. Mills. “Disaggregating Actors in Intrastate Conflict.” Journal of Peace Research 47 (1) (2010): 83-90.

Shellman, Stephen M., Brian P. Levey, and Joseph K. Young. “Shifting Sands: Predicting Phase Shifts by Dissident Organizations.” Journal of Peace Research 50 (3) (2013): 319-336, DOI:10.1177/0022343312474013.

Singer, J. David and Melvin Small. The Wages of War, 1816-1965: A Statistical Handbook. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1972.

Wallensteen, Peter and Margareta Sollenberg. “Armed Conflict 1989-98.” Journal of Peace Research 36 (5) (1999): 593-606.

Wilkenfeld, Jonathan, Michael Brecher, and Sheila Moser. Crises in the Twentieth Century: Handbook of Foreign Policy Crises. Oxford, England: Pergamon Press, 1988.

Footnotes[+]

| ↑1 | This study was primarily funded by the US Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL). The data collected were jointly funded by the US National Science Foundation (NSF: BCS-0904921; SES-0516545) and the US Navy’s Office of Naval Research (N00014- 10-C-0338). We would like to thank Laurie Fenstermacher at AFRL for supporting our research efforts and for her comments, criticisms, and suggestions. We would also like to thank Hans Leonard, Marcia Zangrilli, and Michael Covington for their research assistance. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Icek Ajzen, Attitudes, Personality, and Behavior (Chicago: Dorsey Press, 1988); Catherine A. Cottrell and Steven L. Neuberg, “Different Emotional Reactions to Different Groups: a Sociofunctional Threat-based Approach to “Prejudice”,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 88 (5) (2005): 770-789. |

| ↑3 | David H. Petraeus and James F. Amos, U.S. Army/U. S. Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007). |

| ↑4 | David H. Lake and Robert Powell, "International Relations: A Strategic-Choice Approach," in Strategic Choice and International Relations, eds. David H. Lake and Robert Powell (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999); Stephen M. Shellman, Clare J. Hatfield, and Maggie J. Mills, "Disaggregating Actors in Intrastate Conflict," Journal of Peace Research 47 (1) (2010): 83-90; Stephen M. Shellman, Taking Turns: A Theory and Model of Government-Dissident Interactions (Saarbrucken: VDM Verlag, 2010); Stephen M. Shellman, “Leaders and Their Motivations: Explaining Government-Dissident Conflict-Cooperation Processes,” Conflict Management & Peace Science 23 (1) (2006a): 73-90; Stephen M. Shellman, “Process Matters: Conflict and Cooperation in Sequential Government-Dissident Interactions,” Security Studies 15 (4) (2006b): 563-599. |

| ↑5 | Shellman, “Leaders and Their Motivations”; Shellman, “Process Matters”; Shellman, Taking Turns. |

| ↑6 | J. David Singer and Melvin Small, The Wages of War, 1816-1965: A Statistical Handbook (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1972). |

| ↑7 | Jonathan Wilkenfeld, Michael Brecher, and Sheila Moser, Crises in the Twentieth Century: Handbook of Foreign Policy Crises (Oxford, England: Pergamon Press, 1988). |

| ↑8 | Peter Wallensteen and Margareta Sollenberg, “Armed Conflict 1989-98,” Journal of Peace Research 36 (5) (1999): 593-606. |

| ↑9 | Daniel C. Esty et al, Working Papers: State Failure Task Force Report (McLean, VA: Science Applications International Corporation, 1995), accessed June 8, 2009, http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p312200_index.html; Daniel C. Esty et. al., The State Failure Task Force Report: Phase II Findings (McLean, VA: Science Applications International Corporation, 1998), accessed June 8, 2009, http://globalpolicy.gmu.edu/pitf/SFTF%20Phase%20II%20Report.pdf; Sean P. O’Brien, “Anticipating the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: An Early Warning Approach to Conflict and Instability Analysis,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 46 (2002): 791-811. |

| ↑10 | Philip A. Schrodt, Shannon G. Davis, and Judith L. Weddle, “Political Science: KEDS—A Program for Machine Coding Events Data,'' Social Science Computer Review 12 (3) (1994): 561-88; Philip A. Schrodt and Deborah J. Gerner, “Empirical Indicators of Crisis Phase in the Middle East, 1979–1995,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 41 (1997): 529-552. |

| ↑11 | Doug Bond, Craig Jenkins, and Kurt Schock, “Mapping Mass Political Conflict and Civil Society: Issues and Prospects for the Automated Development of Event Data,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 41 (1997): 553-579. |

| ↑12 | Robert Plutchik, Emotion, a Psychoevolutionary Synthesis (New York: Harper and Row, 1980). |

| ↑13 | Cottrell and Neuberg, “Different Emotional Reactions.” |

| ↑14 | Peter Kuppens et al., “The Appraisal Basis of Anger: Specificity, Necessity and Sufficiency of Components,” Emotion 3 (3) (2003): 254-269. |

| ↑15 | David Matsumoto, Hyisung C. Hwang, and Mark G. Frank, “Emotional Language and Political Aggression,” Journal of Language and Social Psychology XX (X) (2013): 1-17, accessed May 8, 2013, DOI: 10.1177/0261927X12474654. |

| ↑16 | Most dissident activity in the Philippines has been conducted by the Abu Sayyaf Group, Moro Islamic Liberation Organization, and Moro National Liberation Front. In Egypt, dissident organizations include the April 6 Youth Movement, Popular Committee for Supporting the Palestinians, Coalition of the Youth of the Revolution, Vanguards of Conquest, National Association for Change, Muslim Brotherhood, Revolutionary Socialists, and Intifada Solidarity Movement. |

| ↑17 | Plutchik, Emotion. |

| ↑18 | Stephen M. Shellman, Brian P. Levey, and Joseph K. Young, “Shifting Sands: Explaining and Predicting Phase Shifts by Dissident Organizations,” Journal of Peace Research 50 (3) (2013): 319-336, DOI: 10.1177/0022343312474013. |