Özgür Özdamar

Bilkent University

This article provides an introduction to the theoretical underpinnings of expected utility and game theory approaches in IR studies. It goes on to explore their application to a specific research subject, international bargaining on Iran’s nuclear program. In this application, the article presents forecasts about Iran’s nuclear program using a game theoretic, bounded rationality model called the expected utility model (Bueno de Mesquita 2002). Three analyses were made in December 2005, September 2006 and March 2007. All three forecasts appear to be in line with real-life developments regarding the issue. The results show that Iran has been losing international support since the analyses started, and the last forecast suggests a pro-US position supported by all major international actors. Also, all three analyses suggest that Russian and Chinese support is vital to curb the Iranian nuclear program.

1.Expected Utility Model

1.1.Introduction to the model

The expected utility theory was developed to explain decision-making processes under uncertain conditions. Its most basic hypothesis suggests that the expected utility of an actor facing a decision under uncertain conditions is the utility in each state discounted by the actor’s estimate of the probability of each state. Developed by Von Neumann and Morgenstern[1], this theory has been extensively used by social scientists studying human behavior under uncertainty.[2]

In the international relations literature, game theoretic analysis begins with Thomas Schelling’s The Strategy of Conflict[3]. Since then, studies using such approach have burgeoned and contributed to the international relations literature[4]. A small sample of the important works from this literature includes Ellsberg[5], Russett[6], Bueno de Mesquita[7], Bueno de Mesquita and Lalman[8], Martin[9] and Brams[10].

There are various benefits of using this approach. The strategic approach “coupled with its explicit logic, transparency in assumptions, and reasoning and propositions has led to substantial progress in knowledge.”[11] Most importantly, using game-theoretic approaches to international problems increased our understanding of substantive issues such as deterrence, alliance formation, international cooperation and economic sanctions, democratic peace and conflict initiation, escalation and termination.[12]

Likewise, a handful of international relations theories used a combination of game theory and expected utility theory. One of the pioneers of this literature is Bruce Bueno de Mesquita. In The War Trap[13], he develops a marginal utility theory of initiating wars. His works in this particular field of study include Forecasting Political Events: The Future of Hong Kong[14]; European Community Decision Making: Models, Applications, and Comparisons[15]; and Predicting Politics[16]. Bueno de Mesquita uses the expected utility model (EUM) to forecast the future of various international issues, ranging from the Chinese control over Hong Kong to prospects for democratization of Russia and the bargaining on taxing emissions in the EU.

The EUM has become more accepted among international relations scholars in the last decades, as its predictive power is supported by empirical evidence. In a special edition of International Interactions, edited by Kugler and Feng[17], the model was used by leading international relations scholars on issues such as Russian political succession[18], Quebec’s economic and political future[19], NAFTA’s approval and implementation[20], economic reform in China[21], the status of Jerusalem[22] and the settlement in Bosnia[23]. The model has also been used to predict the future of various recent international issues, such as the settlement in Northern Ireland[24], the political future of Afghanistan[25], regional responses to the Iraq war[26] and the future of Iraqi and Palestinian leadership[27].

This approach (i.e. the conflict approach to IR) has also proved to be more successful in making accurate predictions than some other approaches (e.g. Frans Stokman’s cooperation approach) in explaining the European Community’s decision-making procedures[28]. There has been a growing interest in applying this model to the EU’s legislative decision-making that was articulated in European Union Politics journal’s special issue edited by Stokman and Thomson[29]. The conclusion of the volume suggests that the overall testing of the models has shown that bargaining models (i.e. Bueno de Mesquita’s conflict and Stokman’s cooperation models) do much better than procedural models in generating accurate predictions of EU policy outcomes[30].

Due to its proven success in making predictions in the literature, to analyze the energy security policies of the EU and US, I take the perspective outlined by Bueno de Mesquita in European Community Decision Making[31] and Predicting Politics[32] that individual decision-makers consider domestic and international repercussions they can expect to follow from their actions. This approach to understanding future policy decisions implies “to identify tools that shed light on individual incentives and on strategic maneuvers designed to alter or operate within those incentives, taking institutional constraints into account as appropriate”[33]. The theory states that the international system is shaped by the actors who act strategically in their relations to each other. The advantage of using this approach is that it allows taking into account both the domestic factors (e.g. political or economic actors, firms, public opinion, business and interest groups) and systemic pressures (e.g. bipolarity and multipolarity, a balance of power or preponderance of power in the hands of few, liberal or authoritarian rules and norms) that decision makers face in everyday foreign policy-making.

This approach also offers other advantages in analyzing energy security policies of nations or supranational bodies, such as the EU. It allows the researcher to test counterfactual views of foreign policy making. Moreover, game theory is specifically designed to address the logic of strategic action. That is, it captures the essence of international relations in which the actors take into account how other parties will respond to their actions. Interdependencies between states, events, individual choices and strategic maneuvering are the characteristics of energy security issues, as well as many other foreign policy decisions. Therefore, this theory is particularly well-fit to the subject matter at hand. Lastly, the literature shows that game-theoretic analyses have enjoyed considerable success in the areas of explanation and prediction[34].

1.2. Theoretical foundations of the model

The model uses Black’s[35] median voter theorem and Bank’s[36] theorem of the monotonicity between certain expectations in asymmetric information games and the escalation of political disputes[37]. These theorems are the fundamentals of the quasi-dynamic political model that facilitate the analysis of the players’ decisions, such as compromise, bargain, exercising power or compel in a certain bargaining situation. Some basic assumptions of the model are outlined below.

The model assumes that the policy makers try to maximize their expected utility with regards to both policy and personal satisfaction. That is, the policy maker chooses between an alternative policy and personal outcomes. Bueno de Mesquita[38] suggests that there is a trade-off between policy and personal outcomes for a leader. Changing a policy position to make a deal with an adversary, for instance, might bring satisfactory political outcomes, such as the gains from the positive public image as a deal maker; however, the same move can also bring lower personal gains, i.e. the leader’s support from his constituency can decrease due to the concessions given to the rivals to reach the deal. The actors in the game try to maximize their utility with respect to policy and personal satisfaction.

Another assumption of the model is that the players’ information consists of what the player knows about the preceding round of bargaining and expects to happen next. The negotiation rounds run until it is calculated that the cost of continuing negotiations exceeds the anticipated benefit. At this point, the simulation ends. The predicted policy outcome is the position of the median voter in the last round of the negotiations. However, if there are veto players in the game, the outcome is the position of the veto player in the last round. The model does not always predict an agreement: If the players do not converge on an issue, the outcome does not provide an agreement.

The model combines insights from the median voter and monotonicity theorems and allows estimating and simulating the perceptions and expectations of decision makers. The forecaster software creates a game in which actors make proposals to each other in order to influence the others’ policy choices. The expected utility calculations of the players give the analyst insights about whether the negotiations will continue, and if so in what direction and at what point the negotiations will end with what kind of outcome.

More specifically, the EUM forecasts an expected outcome of a policy issue (usually a foreign policy issue) “as a function of competition, confrontation, cooperation and negotiation”[39]. The model is able to delineate possible solutions that the actors are not aware of by providing the researcher with alternative paths of strategic action that can produce different resolutions of the issue at hand[40]. The model is also used in the academic fields of political science, economics and sociology because of its axiomatic foundations and rigorous specifications of the various dimensions of the issue.

The EUM defines policy choices as a product of competition between political actors who make policy decisions. In this sense it is a non-cooperative game. The game is constructed in such a way that different actors suggest diverse policy proposals to each other to induce support – or opposition - from other players. Sometimes the actors are powerful enough to make credible proposals and to change other players’ positions, sometimes they are not. In such cases the cost of trying to change the others’ position may be very costly. It is assumed that the actors, in each round of bargaining, make expected utility calculations.

According to the model’s logic, the bargaining rounds continue as long as the players think continuing negotiations is better – or less costly - than giving up. If a player encounters a situation in which continuing negotiations will generate more costly results, maintaining the status-quo appears to be a better alternative than making more proposals to change the other actors’ positions. While engaging in bargaining, there are two basic factors that affect decision makers: estimates of the expected utility to be gained from choosing (a) alternative policy proposals, and (b) the policy satisfaction to be gained from making such a deal plus the personal cost of such a political move for the leader, as the leaders calculate how reaching such an agreement will affect their reelection or staying in power. Their decision about maintaining the status-quo or making further policy proposals results in predictable policy decisions for the issues in question or in failure to reach an agreement[41].

1.3. The three variables: capabilities, policy position, salience

In this section, the nuts and bolts of the EUM’s functioning and the data required are presented. The model is a game in which the actors simultaneously make policy proposals to each other to influence the others’ decision. Proposals are different points on the policy continuum. Players evaluate other policy proposals and they are assumed to create coalitions by shifting positions on the issue in question. The analysis is carried out by evaluating each round that players are engaged in. The rounds are played sequentially until the issue is resolved, i.e. a player or players shift position, make a deal etc.- or maintaining negotiations becomes costlier than the benefits one can achieve. In each game, each player knows three factors: (1) the potential influence (capabilities) of each actor on the issue examined; (2) the current stated policy position of each actor on each issue examined; and (3) the salience each actor associates with the issues in question. The actors do not know what each actor associates with alternative outcomes or their perception of risks and opportunities. As in many international relations games, each actor has its own perceptions about the other actors and makes its moves based on these perceptions, sometimes in error[42].

A player’s potential influence (capabilities) on the issue depends on how much power and resources this actor can allow on the issue concerned. If the actors are nation states, for instance, the power or potential influence of the country on the issue might not include all of the resources the country has available. It is rather the pool of resources that a country can allocate to the specific issue. However, if the issue is related to an international crisis that can lead to a full-scale war, then all the resources of the country might reflect that country’s potential influence. A convenient way to determine players’ potential influence is to code 100 for the most powerful stakeholder on the issue and determine the other actors’ influence relatively. For example, in a study conducted about the disarmament of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) using the EUM, the IRA’s influence was coded as 100 while Sinn Fein and the UK Executive’s capabilities were both coded as 80. Having practically no influence on the IRA’s decisions, the Northern Ireland Unionist Party’s influence was coded as 2.[43]

Second, the current stated policy position represents the actors’ chosen position between policy satisfaction and personal security for that actor. Therefore, it is not the best or most preferred position for the actor nor is it the outcome that the policy maker expects to achieve. In the same study on disarmament of the IRA, the UK Executive’s and opposition’s policy positions were coded as 90 and 100, the latter representing the strictest position against IRA arms. Although the most preferred outcome for the UK Executive would naturally be the total disarmament of the IRA, their coded negotiation position represented a slight discrepancy from the strictest position for various reasons.

Third, the salience scores show how important the issue is to the actor. In other words, the players decide how to distribute resources across issues according to their preference[44]. The salience score indicates how important the particular issue is for the actor compared to other issues. Bueno de Mesquita[45] suggests that assigning high values of 90-100 for salience indicates an issue is of utmost importance; 50-60 would mean the issue is one among several important ones, and 10-20 stands for an issue of minor importance to the actor. To give an empirical example, in a study conducted about the preference for economic system in Afghanistan after the coalition-led overthrow of the Taliban regime, the salience was coded as 99 for Osama bin Laden while for regional actors such as Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan it was 20. The divergence between the scores show the economic system was of utmost importance for bin Laden while for some regional actors it was a minor issue.

The forecaster program requires these three values to be defined for each actor in order to run an analysis. It is strongly suggested to resort to the knowledge of area experts to determine the values for the three variables. In fact, the whole success of the model depends on reliable data gathered from area experts.

1.4. Limitations

The model has limitations as well as strengths. One limitation arises from its imprecision in predicting the exact timing of the decisions made. Another problem is that there is no ‘objective’ data for many of the issues at hand. Because of that, the knowledge of experts about the issues of concern is required.[46] However, collecting the related data using expert interviews is also a challenging and cumbersome task because it requires time and funding.

The main specific difficulty related to the interviews conducted for the study presented in this article was to explain to area experts the mathematical model that they were supposed to consider while answering questions. Such an understanding is crucial because, otherwise, it is generally difficult to objectively assign values to positions analyzed in the model since the EUM model requires numerical values assigned to variables in a relative manner. Therefore, it was important to carefully explain to the area experts the principles and working of the model, and once these principles were understood, area experts were able to assign numerical values to the analyzed positions vis-à-vis each other in a relatively easy fashion. Hence, conducting such interviews is challenging in terms of both research-specific and general practical issues.

Moreover, creating a model to predict complex political events requires simplification, such as, the issues are assumed to be unidimensional. Such a task in turn requires a higher level of abstraction but may suffer from losing some details. This does not mean the model is not rigorous; however, it should be noted that such a model cannot be built without such a simplifying effort. Lastly, the interpretation of the timing of the results is rather an art than a science because the model does not provide a definite time frame for the estimated results.

2. Personal History with Respect to the EUM

I used this theory, its methodology and software to produce short-term forecasts regarding the Iranian nuclear crisis in the 2005-2007 period. My graduate education emphasized methods training more than any other field such as IR or comparative politics. Among all quantitative methods I was most interested in game theoretical modeling due to its analytical rigor. After taking three courses in game theory, I was most interested in an approach combining game theory, expected utility theory, traditional area expertise, and agent-based modeling with computer simulations. I also considered such alternative methods as a traditional historical approach or case study method since these studies have some advantages and disadvantages. Using the traditional approaches, researchers can have more details and less abstraction in their work; however, these approaches do not have modelling’s benefits of precision and simulation. Thus, I preferred the expected utility modeling and game theoretic simulation, which in contrast to the above-described methods, combines the advantages of both traditional area expertise and state-of-the-art modeling. This computerized method allows for agent-based analysis of multi-actor complex interactions, which the complex case of Iran exactly fits. Thus, while conducting research for my PhD dissertation I used this method to analyze three episodes of the Iran nuclear program in 2005, 2006 and 2007.

I was trained in game theory but not specifically for this particular method. Thus, I learned it mostly by self-study. I occasionally relied on the help of Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, the scholar who introduced this method, for advanced issues that I could not resolve myself. I believe this is a very rigorous method with sound scientific background, but it requires a background in mathematics, game theory and economics to adopt it. The main challenge I faced while using such method is that you can never acquire the copyrighted software and full information about its source code. For example, the software used for this research is called ‘Dynamic Expected Utility Model’ which is owned by the New York based company Decision Insights Inc. Such analysis is also performed by a second company named Sentia Group, located in California. Due to such private ownership and strict copyright rules, researchers have to rely only on the output files provided by the software.

3. Iran’s Nuclear Program: Introduction[47]

Iran is a key actor affecting the political stability of the Middle East and the global energy markets. An isolated Iran in a crisis situation regarding its nuclear program is a threat to the world’s political and economic security. Given the problems the US and its allies face in Afghanistan, Iraq and regarding the Israeli-Palestinian question during the first decade of 2000s, Iran’s attitudes and actions in the region were considered to be vital.[48] More specifically, overthrowing the regimes in Afghanistan in 2002 and Iraq in 2003 resulted in the unintended consequence that Iran’s “rivals” (Taliban, al-Kaida and Saddam Hussein) were neutralized by the US-led coalition forces. Allegedly, this situation has given Iran an opportunity to increase its influence over the region since then, boost support for terrorist groups and become an important actor in Iraqi politics by exercising influence over the Shia majority. This view has become so prevalent that Israel’s bombing of Hezbollah in southern Lebanon during the summer of 2006 was perceived as a proxy war between the US and Iran.

Iran’s stability is also vital for the world economy. Its vast oil and gas resources are critical for the security of the energy supply to the world markets. There are two factors that contribute to Iran’s important role for global energy security: the volume of its resources and production, and its geographical position in the center of energy transport routes. Iran holds the second largest oil reserves (following Saudi Arabia with 11.4% of total), as well as gas reserves (following Russia with 15.5% of total) in the world. In 2006, Iran was the fourth largest producer of oil and natural gas in the world. As of 2007 its oil production is estimated to be at an output quota of 4.3 million barrels per day (about 5.4% of the world production), and there is more oil and gas potential that has not yet been revealed[49].

Second, many see Iran as the most attractive route for Caspian oil and gas. It also has the potential to supply oil and gas to Central and Eastern Asian countries. It even controls the Hormuz Strait and thus the transportation route for a substantial amount of Middle Eastern oil resources. These political and economic concerns make the stability of Iran and the de-escalation of the conflict surrounding its nuclear program of great importance for global security today. A military operation or imposing comprehensive economic sanctions can seriously threaten the delicate political balances in the region and dramatically increase global oil and gas prices.[50]

4. Model Application Example: Forecasting the Future of Iranian Nuclear Issue

To evaluate the dynamics of this conflict and forecast the future developments, I used the dynamic expected utility model described in the first section.[51] There are various benefits of using this approach. One of them is it provides analysts an opportunity to apply systematic means to evaluate alternative processes and outcomes to the issue at hand. Furthermore, the model has been extensively tested against various issues of nature in real time and its success in forecasting unknown outcomes is supported by empirical evidence[52]. The EUM helps in understanding which policy outcomes are likely to emerge as well as the nature of interactions, conflicts and coalitions that may emerge among the actors. An analysis of Iran’s nuclear program in 2005, 2006 and 2007 based on EUM is presented in the next section.

4.1. Expert-generated data

Experts[53] who specialize on Iran and Middle Eastern politics were asked to identify relevant stakeholders (actors) and generate the coding of their policy positions, capabilities and salience they attach to the Iranian nuclear issue. The coding took place independently in December 2005, September 2006 and March 2007.[54] The experts received very detailed instructions about how to code the data.[55] Due to limited space, I briefly report the findings of the two earlier forecasts and then focus on the forecast from March 2007 regarding the application of the method to the case.

4.2. First analysis and forecast: December 2005

The first data were collected in December 2005. At this point, the so-called EU3 countries had increased pressure on Iran to stop enrichment activities in Isfahan and not to begin enrichment at the other plants. Because the Iran-EU3 negotiations were stopped in August 2005 Russia’s proposal to resolve the issue was at the center of the discussions.

The issue continuum includes three major policy positions for the stakeholders. The data were coded by an experienced analyst who has specialized on Iran for over twenty five years. All Iranian actors’ positions were represented by 100, defined as “Continue developing nuclear technology that can be used to produce nuclear weapons” by the expert. On the other extreme of the continuum is Israel’s position, i.e. “No uranium enrichment at all”, represented by 0. China’s position (85) was the closest to Iran’s, owing to its close economic ties with the country. While IAEA’s position was 60, rest of the actors’ positions were coded as 70, which represents “Continuing transferring of nuclear technology to Iran but uranium enrichment made in Russia”. After the collapse of negotiations between the EU3 and Iran, this “moderate” position was subscribed to by the US, EU, India, Pakistan, regional powers such as Saudi Arabia and Russia itself as the initiator of the proposal.

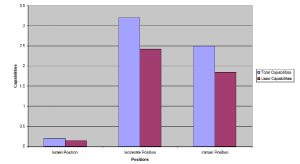

Figure 1 reveals the total and used capabilities[56] by positions. The first group holds the largest share of capabilities (the moderates); it includes the US, the EU3, the EU Commission, India, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Russia and the IAEA. The second group includes Iranian actors, i.e. the Iranian Supreme Leader, Iranian government (President Ahmedinejad –Hawks-), the parliament (Majles) and also China. Lastly, Israel represents its position as a single actor.

Figure 1: Total and Used Capabilities by Position (December 2005)

Figure 1 shows that the group that has the most power subscribes to the moderate position group with 55%, while the actors close to the Iranian position represent only the 42% of the total capabilities. A realist account of international politics would expect the moderate group to deter Iran from enriching uranium. However, the strategic interactions between actors result in different conclusions than one would expect by observing the mere power distribution. The more influential actors do not necessarily achieve their favorite policy in international politics, as the following discussion will illustrate.

The expected utility analysis concluded that the bargaining on Iran’s nuclear program in this time period would result in an outcome that strongly favored Iran. The estimation of the model, after three simulated iterations, is 100, which is the Iranian position that favors continuing uranium enrichment. The analysis therefore indicated that Iran would not give in to international pressures and continue developing its nuclear program as it was planned, i.e. begin enrichment in other facilities. The data were received from the area expert in December 2005. At this point, the international community doubted whether the negotiations with the EU3 would resume, the deadlock would endure or whether Iran would choose to escalate the situation. In January 2006, the Iranian government declared it would restart its nuclear program. The data was finalized and the analysis completed in December 2005, before the Iranian government’s decision to resume enrichment-related activity in January 2006. Although there is no hard rule about how frequently the analyses shoud be repeated to capture changing dynamics of an issue, the general practice is to consider a prediction valid for six months and repeat simulations afterwards. Considering the six months time frame after December 2005, this initial simulation predicted the outcome of the bargaining about Iran’s nuclear program correctly.

4.3. Second analysis and forecast: September 2006

The second set of data was coded by a different area expert in September 2006. The expert, a native of Iran, focuses on Middle Eastern and Iranian politics and has worked for various think tanks in the region. The rapidly changing dynamics of the issue requires collecting data on the three variables over time. Therefore, the first analysis is updated with later data collections.

The issue continuum defined by the area expert is shown in Table 1 and 2. At the one extreme is Israel’s position, which is defined as “No uranium enrichment at all” and represented by 0. The expert suggested that Israel favored strict IAEA inspections and considered military operation to be a viable option in case diplomacy did not work. The US and UK’s positions (15 and 20 respectively) are the closest to Israel’s, meaning that both are against uranium enrichment and weaponry technology by Iran but still favor a “diplomatic” solution if can be reached. On the other hand, after the failed negotiations with Iran between 2003-2006, the EU also changed its attitude. The expert’s coding captured this change. The EU’s (except the UK) position was coded as 30, which favored continuing the use of diplomacy but called for intensifying the use of economic sanctions targeting the nuclear program. The regional Arab countries’ position was very close to the EU’s.

The largest group of countries in the simulation subscribed to a rather “compromise” solution. Represented by Russia, China, Turkey, Pakistan and India, these countries approve of the peaceful use of nuclear technology despite their resentment towards the production of weapon grade material by Iran. As a policy tool this group still favored using negotiations.

Lastly, Iran’s internal politics were represented by three groups or individuals. First, the expert suggested that despite their declined influence, an opposition group headed by former president Khatemi and Rafsanjani favors suspending the enrichment and returning to negotiations with the EU. Their aim is to take the issue from UNSC domain to an IAEA problem. On the other hand, the expert also made a distinction between the Supreme Leader Khamanei’s and hawkish groups’ (including then president Ahmedinejad’s) perspectives on the issue. By the fall of 2006, the expert claimed that Iranian internal balance of power had turned against President Ahmedinejad, and his furious comments about the nuclear program and Israel were – despite any public comments - condemned by the Mullahs. This expert suggested that the Supreme Leader supported the nuclear program, however, only up to the point that it starts threatening the survival of the Islamic regime. The Iranian hawks’ position was described as the will to continue developing nuclear technology that can be used to produce nuclear weapons and leave almost no room for concessions. Therefore, their respective positions were coded as 70 and 90.

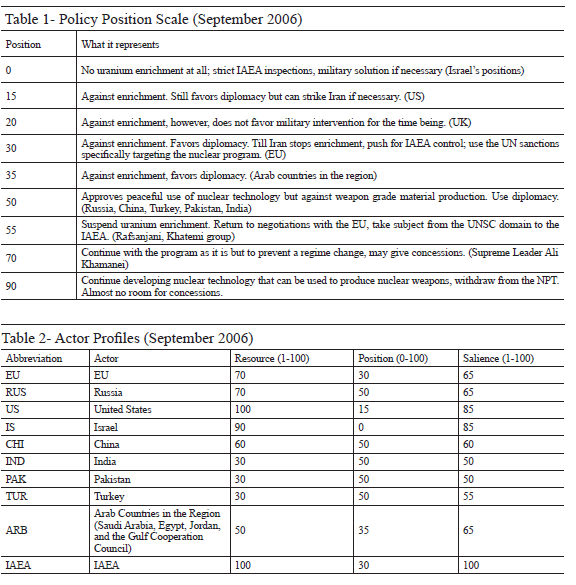

The total and used political capabilities that can be exercised by actors on the Iranian nuclear issue are shown in Figure 2. After negotiations with the EU3 collapsed and Iran rejected the so-called Russian proposal in January 2006, we see a diversification of positions. As of December 2005, the moderate position was dominant. In the fall of 2006, we observe that the Western powers shifted to a less pro-Iranian stance. In fact, the group that has the most effective bargaining power is against uranium enrichment in Iran and considers the military option a possibility. The EU position gathers the third largest support, which is very close to the second compromise position. I believe the area expert correctly represented the changing dynamics of the bargaining: after the failure of negotiations, France and Germany subscribed to a more skeptical outlook on Iran while the US and UK began to announce that they would not allow Iran to acquire nuclear weapons capabilities and also did not rule out a military option.

Figure 2: Total and Used Capabilities by Position (September 2006)

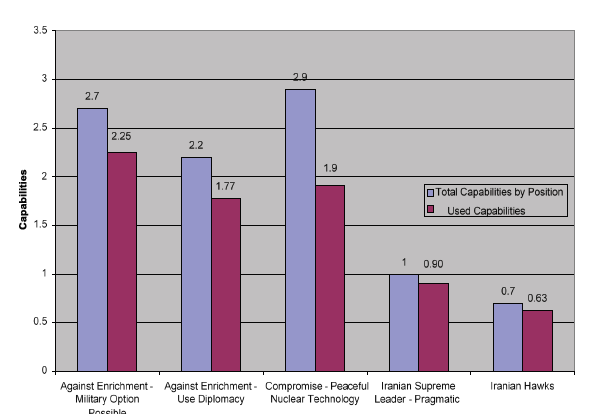

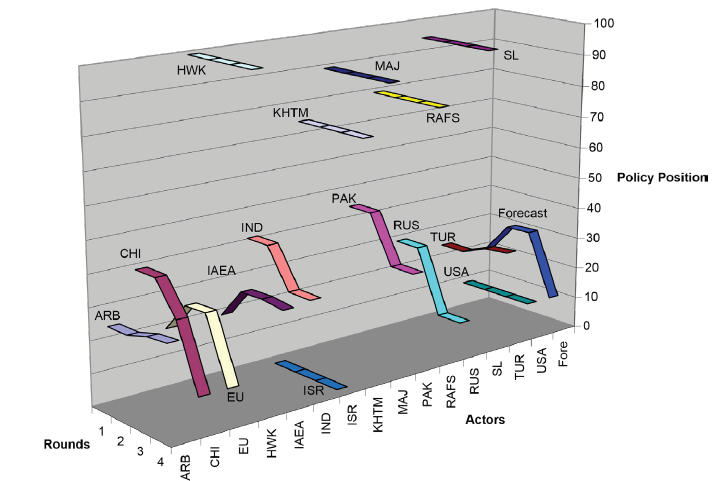

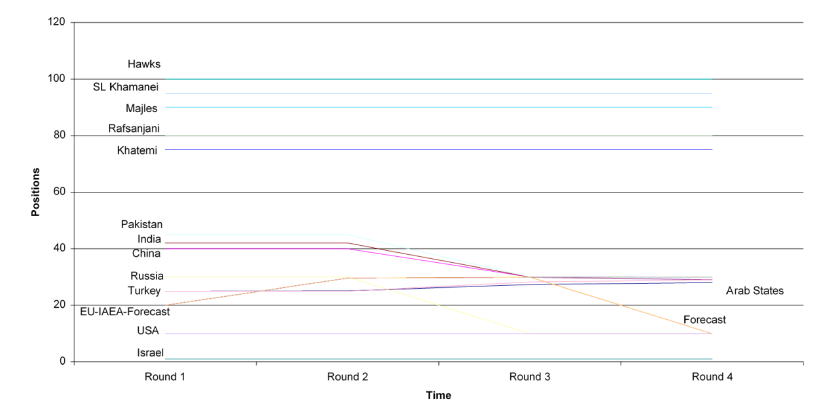

Figure 3 shows the simulation of political dynamics regarding the Iranian nuclear issue as of fall 2006. The rounds of bargaining are plotted on the x-axis. “Rounds” are contextually defined as time frames of a simulation in the expected utility model. The z-axis shows the policy positions of actors while the y-axis denotes the actors. One can observe how the positions of each actor and the forecast of the model changed round by round during the simulation. The forecast of the simulation was the EU position (30) at the end of the fifth round of bargaining.

Figure 3: Political Dynamics on Iranian Nuclear Issue (September 2006)

The EU position is against enrichment taking place in Iran. This position favors using diplomacy and UN sanctions specifically targeting the Iranian nuclear program. This forecast, presented in September 2006, accurately predicted the outcome of late 2006. On December 23, a UN Security Council resolution was passed that initiated sanctions specifically targeting Iran’s nuclear program. When the initial positions are reviewed, although the EU proposal bore the third largest bargaining power, it was able to draw support from the US, the UK[57] and Israel, which ended up in the EU’s position. This reflected the nature of real bargaining that took place where countries led by France and the IAEA asserted that a “smoking gun” was not found and diplomacy and sanctions should continue as the predominant policy option.

4.4. Third analysis and forecast: March 2007

The latest set of data was collected in March 2007.[58] The area expert, who specializes in Iranian politics and recently returned to Europe after having lived in Tehran for several years, was asked the following question: “What is the attitude of stakeholders toward the nuclear program of Iran?” The expert was asked to define the stakeholders and articulate the approaches of each actor and corresponding policy options. This means that every policy position was defined both in terms of the stakeholders’ attitude toward the program and their policy preferences, such as using force to destroy the Iranian nuclear program, using economic sanctions only targeting Iran’s nuclear program, using sanctions targeting the Iranian economy as a whole or allowing the peaceful use of nuclear energy in Iran.

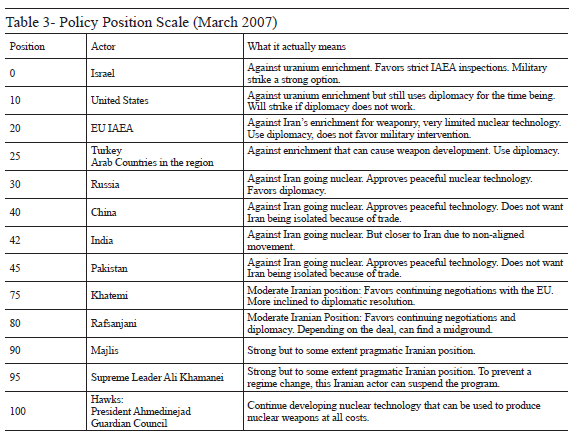

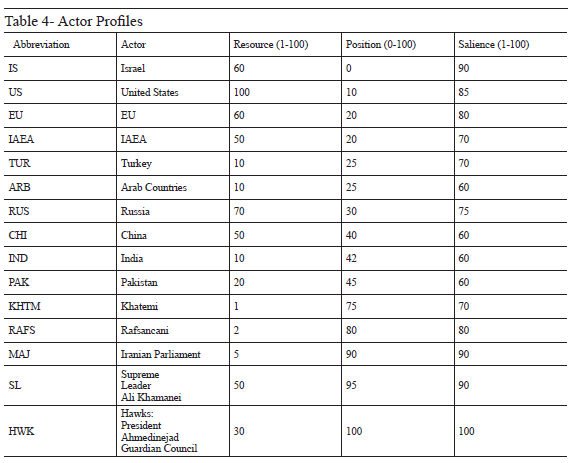

Table 3 presents a range of attitudes stakeholders subscribe to, from the outright opposition against Iran’s nuclear program to the position favoring a full nuclear fuel cycle within Iran that can be used to produce nuclear weapons. The area expert carefully determined very specific policy positions and corresponding attitudes and policy preferences numerically. The expert was asked to justify each position value and the distance between those positions during the interview. What the positions represent in terms of attitudes and policy preferences is explained in the third column of the Table 3.

The policy positions disclosed in Table 4 show a significant change in the stakeholders’ attitudes towards Iran’s nuclear program by March 2007. The new coding represents the changing international opinion on Iran’s nuclear program and increasing skepticism about its intentions. While Israel and the US maintained their positions since 2006, we observe that the EU, IAEA, Turkey and the region’s Arab actors gradually shifted to a less pro-Iranian stance on the nuclear issue. In fact, a close observation of public statements of these actors shows that the international community at this point had stronger doubts about the “peaceful” nature of the Iranian nuclear program. An even more striking change was the position shift of Russia and China. The expert who coded the data clearly stated that Russia and China were against Iran becoming a nuclear power. Although these two countries blocked sanctions against Iran during the 2003-2006 period, their attitude seems to change by late 2006 and during 2007. The most obvious indicator of this change was that Russia and China voted for the Security Council resolutions 1737 and 1747 against Iran’s nuclear program in this period. This, of course, changed the balance of power against Iran.

The third expert also suggested a changing balance of power within Iranian institutions. Similar to the second expert’s views, this coding also reflected a difference between Iranian Supreme Leader Khamanei’s and the Iranian Hawks’ positions and power. According to the experts’ views, international pressure convinced the Supreme Leader that although the development of a nuclear program was Iran’s right, it could be suspended to prevent regime change, while the Hawks considered maintaining the program at all costs. During the interview, the expert also mentioned that the Supreme Leader and the Mullahs did not favor Ahmedinejad’s high-profile attitude about the nuclear program and considered it as a threat to the Islamic regime. The bargaining power of the Supreme Leader is significantly higher than Hawks’ in the coding. Such coding reflects the institutional structure of the Iranian system, as well as the balance of influences at the time on the nuclear issue in Iran.

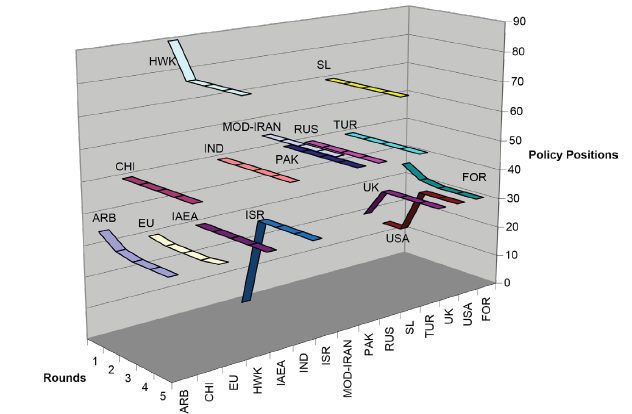

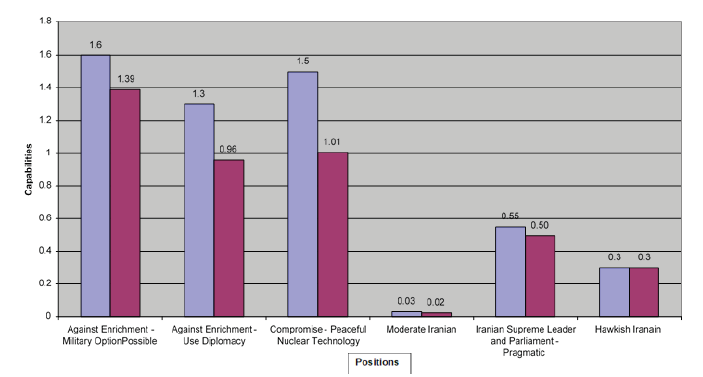

Figure 4 shows the dynamics of the Iranian nuclear issue in terms of the total and used capabilities variables. Although the absolute values changed, the values for the relative capabilities of actors’ vis-à-vis each other remain similar to those of the September 2006 data. This shows that no actor significantly changed the resources that can be devoted to the issue. The most powerful position is still the position that considers expanded economic sanctions and military intervention as a possibility if Iran maintains enriching uranium that can be used to produce nuclear weapons. The important point, however, is that Turkey and regional Arab countries came closer to the EU’s position, while the position of compromise actors (Russia, China, India and Pakistan) also moved to a less pro-Iranian stance on the issue continuum. That is, although the term “compromise” is still used for consistency, these four actors’ position in 2007 was further away from Iran compared to the September 2006 coding.

Figure 4: Total and Used Capabilities by Position (March 2007)

Figure 5 illustrates how the actors changed their positions during each bargaining round. After four rounds of bargaining, the EUM’s forecast was the US position, which is represented by 10. That is, the analysis of March 2007 concludes that the bargaining on the nuclear program of Iran was likely to end with a policy option then favored by the US. According to the definition of the expert, the US was against Iran’s then enrichment practices. In terms of policy preferences, the US still preferred diplomacy; however, if it believed the ongoing efforts would not work, it would push for wider sanctions and would not hesitate to use force against Iran’s nuclear facilities. This means, based on the data collected in March 2007, the forecast suggested the US’ position of not allowing Iran to acquire nuclear weapons capability was likely to succeed, as the real-life events also concluded in 2013 and 2015.

Figure 5: Political Dynamics on Iranian Nuclear Issue (March 2007)

Figure 6 shows the position shifts of Iranian and other actors during the bargaining. An analysis of these shifts is important because it gives important insights into the possible future development of the situation. According to the analysis the range of outcomes supported by Iranian actors did not change during the bargaining. No Iranian actor was compelled by other Iranian or non-Iranian stakeholders to change his position. For Iranians, the range of outcomes was stable in the 75-100 range, which means no Iranian actor considers giving in to the pressures by other international actors. For all non-Iranian stakeholders, on the other hand, the range of acceptable outcomes initially was in the 0-45 range. As the rounds progressed, this range shrunk to 0-30. Therefore, the model predicted that Iran was likely to lose even the moderate support it was receiving from actors like China, India, Pakistan and Russia. The significant discrepancy between Iranian and non-Iranian actors’ positions shows that there was no middle ground the actors could agree to and that Iran was more likely to be isolated in the near future. The data and the forecasts after December 2005 also showed such a trend. Since then the range of outcomes supported by non-Iranian actors dropped from 30-70 levels to 0-30. This shows that international support and the legitimacy of Iran shrank as skepticism about Iran’s intentions increased and a deadlock continued. Indeed, the crisis went on until 2013, witnessing even US threats of air strikes in 2009 and additional UN security council sanctions imposed before 2010 and showing decreasing international support to Iran[59].

Figure 6: Stakeholders Position Shifts and Range of Outcomes Supported (March 2007) (Iranian Actors: 75-100. Rest of the Actors: 0-30)

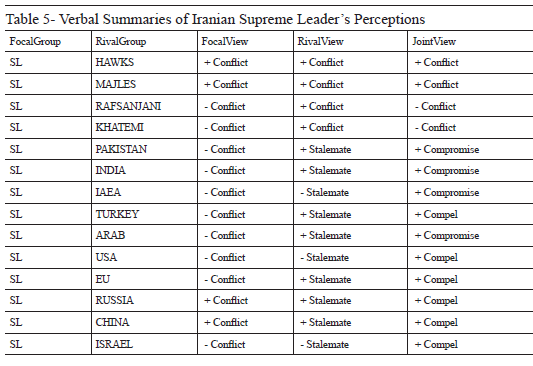

The EUM also takes the perceptions of stakeholders into account to analyze expected relationships regarding the issue. This is accomplished by studying the relationships between each pair of stakeholders (Bueno de Mesquita 2003). That is, one can analyze how pairs of actors perceive each other’s intentions, both numerically and verbally. Table 5 shows the verbal summaries of Iranian Supreme Leader’s perceptions at round 4.

The employed model is based on certain logical conditions regarding the inferences about the behavior of actors and the end of the bargaining. If a player believes that challenging a rival is gainful for him and also believes the rival agrees with this assessment, then the former expects the latter to either compromise or give in to coercion. A compromise occurs if the challenger’s demand is greater than what the rival thinks is necessary to give. Coercion occurs if the challenger’s demands appear to be a smaller utility loss for the rival than the rival expected them to be. A continuation of the status quo or stalemate occurs if a player and his rival believe making further proposals to each other will induce losses. And finally, if a player and his rival believe they will gain from challenging the other and expect to win, then conflict is expected between the parties[60].

The verbal summary table is employed to study the perceptions of the actors. The third column (Focal view) presents what kind of a relation the challenger is expected to have with the rival actors listed. The fourth column shows what the challenger believes the rival thinks. In the fifth column appears what the predictive model proposes about the type of relationship that will appear as a result of the interaction when everyone acts according to these expectations.

Note that a “+” sign indicates that the focal group is expected to have an advantage while “-” indicates the rival is expected to have an advantage. “Conflict” means both actors expect to gain from challenging each other. “Compromise” means either the rival “+” or the focal group “-” is expected to shift its policy stance toward the other. “Compel” indicates either the rival “+” or the focal group “-” is expected to acquiesce by accepting the policy stance of the other player. “Stalemate” indicates the status quo will continue[61].

Let us analyze the perceptions of the Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamanei at the end of the bargaining (Round 4) in the simulation based on 2007 data. In the third column (Focal view), we observe that the Iranian leader’s perception of his relation with all the other actors was one of conflict. That is, he perceived a conflictual relationship regarding the nuclear issue with both Iranian and non-Iranian actors. The directions of the relationship, represented by (-) and (+) signs are important to note. Ali Khamanei expected to gain from challenging all the rivals, however, according to his anticipation, the US, the EU, Israel, and other regional actors with the minus sign were expected to be advantageous in such a confrontation. The fourth column shows what the Supreme Leader believed the rival actors believe. The EUM makes an analysis of expected relationships between the actors based on these two perceptions. The last column (Joint view) denotes that. According to this analysis, if all actors make moves based on these perceptions, the model predicts the Iranian leader would “compel” in favor of the US, the EU, Israel, China, Russia and Turkey. That is the top Iranian decision maker was, at the time of analysis, expected to be forced by influential global and regional actors to give assurances about the nature of Iran’s nuclear program. The most critical point is that, according to Khamanei’s perceptions, the cost of challenging the rivals such as the US was still less than the benefits associated with it. However, the EUM’s forecast was fairly stable in the sense that no pro-Iranian resolution to this problem could be observed in the six-months period following the analysis in 2007. The difference between a leader’s perceptions and reality when making foreign policy decisions is crucial to understand seemingly “difficult to understand” decisions. This analysis shows that Khamanei still expected to gain from challenging other stakeholders although the international opinion did not favor his position anymore, just like North Korean leaders have done since the 1990s.[62] [63]

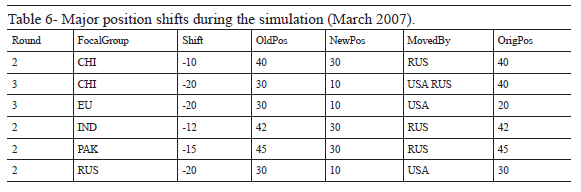

Finally, the major position shifts by stakeholders during the bargaining can be observed in Table 6. The EUM provides a detailed account of shifts by each actor during the iterations of the game. A general overview of shifts by the most influential actors shows that the US drew support from China, the EU and Russia, which made a significant difference in the outcome. Reviewing such shifts is important to produce concrete policy prescriptions.

In round 2, Russia was given a proposal to shift from 30 to 10 by the US, which turned out to be credible. The EU also received an identical proposal in round 3 which caused a shift to the US position. The significant change of the Chinese position came in the third round when the US and Russia convinced China to shift to the American position. India and Pakistan as important regional powers were also convinced to shift their positions by Russia.

The analysis showed that there was a great likelihood that Russia and the EU could be convinced by the United States to move to a more pro-American position at the time of the analysis during 2007. Such a move could have two significant effects on US policy. First, two of the most influential actors in world politics would join the pro-American camp on the nuclear issue. Second, the analysis showed Russia could make a significant difference in terms of drawing support from non-western powers such as China, India and Pakistan. In rounds two and three, Russian credible proposals caused significant position shifts by those three actors towards the American position.

5. Advanced Methodological Features of the EUM: Simulations and Alternative Scenarios

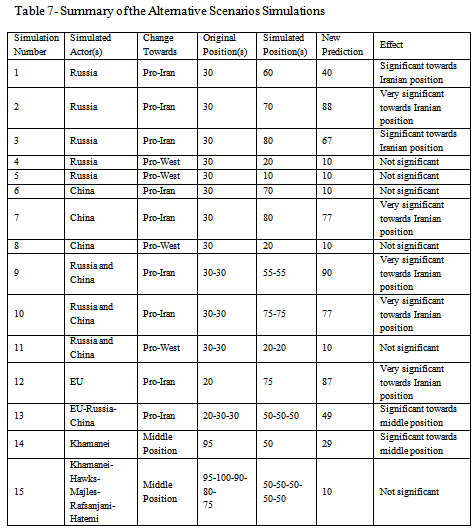

A major advantage of using EUM is that researchers can create alternative future and historical scenarios to analyze different paths to the actual events. Simulations can be designed to model possible changes in stakeholders’ attitudes that cannot be foreseen at the time. This can be done by simulating any combination of the three variables. To create alternative future scenarios regarding the Iranian nuclear program, I ran more than thirty alternative simulations where stakeholders changed their initial positions while the resources and salience variables remained the same. As discussed above, these simulations were made to predict the six months following the coding and analysis in March 2007.

Table 7 presents fifteen of those scenarios that produced some interesting results. These simulations produce important insights for policy makers dealing with the Iranian nuclear program as they create alternative resolutions to the problem. Using scenarios is necessary because researchers and area experts may not always be aware of all the inputs that influence the real policy-makers, as well as unforeseen events (such as external shocks) that may change the actors’ attitudes and so the course of history; the simulations can help therefore in covering the consequences of such unknown changes and events.

Table 7 illustrates possible position changes by the most influential actors. In all three forecasts, a careful review of hundreds of pages of output by the EUM showed that there were three most influential actors causing change in the outcome of the bargaining: China, the EU and Russia. The United States and Iranian actors also brought about changes; however, because their stances on the issue seemed fairly constant, I focused on simulating the other three actors’ positions that might cause a change.

The first five simulations reproduced the Russian position. Russia has a traditionally large influence on world affairs as a former superpower and even more on the regional affairs concerning it. Considering the Russian-Iranian trade relations and including nuclear technology, Russia’s effect becomes even more important to consider. The third column represents the change of position towards a pro-Iranian, pro-Western or middle stance; the fourth and fifth columns show the actor’s original and simulated initial positions respectively. The sixth column shows the model’s new prediction while the last one briefly illustrates the size of the effect. The first three simulations move Russia to a more pro-Iranian position.[64] These three simulations show that if Russia can be convinced by Iran to move to a more pro-Iranian position, the bargaining is likely to end in a position favoring Iran. Especially when the Russian support is at 70, the forecast is 88, which is fairly pro-Iranian. This shows that, for western actors, Russian support in dealing with the Iranian nuclear program is vital to achieve favorable results. For American and European policy-makers, Russian support is necessary in Middle Eastern, Caucasian and Eastern European affairs and challenging it may bring more losses than benefits. On the other hand, when the Russian position is shifted towards more western positions, there is no significant change in the outcome. That is, the current levels of Russian support in dealing with Iran must be maintained and the western actors should encourage Russia to eschew positions more supportive of Iran.

China has also been one of the most influential actors, however its effect did not appear to be as large as Russia’s during our three analyses. Only after the Chinese position becomes significantly pro-Iranian does the model’s prediction change towards the Iranian position. Simulation number 7 shows that if China becomes fairly pro-Iranian (i.e. its initial position is 80), the model’s prediction is 77.

What could be the effects of a Sino-Russian alliance on the Iranian nuclear issue? Such a scenario is not a remote possibility. In fact, it is frequently argued that China and Russia currently attempt to balance the American domination in world politics. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization as a mutual security setting where Russia and China are founding members and Iran is an observer, is suspected to reach this aim. In fact, during the 2003-2006 period, Chinese and Russian policy makers prevented a UNSC resolution against Iran. What if Russia and China decide to protect Iran from western pressure and isolation? Simulations 9 and 10 show that the combined effect of a Sino-Russian coalition may prove supportive for Iran in breaking isolation and maintaining its nuclear program. If China and Russia move a little more to the so-called moderate position (i.e. 50) then the forecast of the model is a strongly pro-Iranian outcome (i.e. 90). This possibility sent a warning message to policy-makers back in 2007: If Russia and China shift to a so-called moderate position that allows transferring nuclear technology to Iran for peaceful purposes, it is likely that Iran will achieve the time and room for maneuvering that is necessary to acquire nuclear weapons production capabilities. The real-life developments that took place in 2015 also confirmed the significance of these simulations. Only after Russia and China agreed with the other Western powers (P5+1) in 2015 and applied pressure on Iran was there a resolution to the issue.

Simulating the EU’s position did not produce significant changes. Only when the EU adopts a significantly pro-Iranian position (Simulation 12), which is difficult to expect in real-life politics, do the forecasts produce a pro-Iranian result. Simulation 13 shows a different situation. In this scenario all three influential actors shift to a moderate position (50). This is a possible scenario if China, the EU and Russia aim to balance the US’ policies in the Middle East, like in the case of the Iraq War in 2003. The prediction of the model in such a scenario centers around the moderate position. That shows if Iran can convince these three actors that its nuclear program is for peaceful purposes, there is a great chance that under the condition of allowing thorough inspections, its nuclear program can be maintained.

Finally, the Iranian Supreme Leader’s and all Iranian actors’ positions are simulated in simulations 14 and 15 respectively. The first alternative scenario demonstrates if the Supreme Leader adopts a middle position then the Iranian nuclear program loses ground. The model predicts the initial Russian position (30) in March 2007 that suggests maintaining the Iranian nuclear program with very strict inspections to prevent weapon grade material production. In a not-so-likely scenario in which all Iranian actors support a moderate position (50), the model predicts a pro-US position as a resolution. This reflects the unfortunate nature of real-life politics for Iranians: if they aim to cooperate with Western forces and adopt a moderate position, there is a great possibility that eventually Iran will lose control over its nuclear program and will have to give in to western demands. Perhaps this explains why the Iranian Supreme Leader and Hawks have adopted a non-cooperating position since the beginning of the bargaining.

To sum up, in 2007 I concluded that Russia’s and China’s support was a must if the US, European and regional policy-makers want to achieve favorable results such as preventing Iran from going nuclear. In 2007 this analysis concluded: ‘without the support from these two important powers, it will be more than challenging for the US and the EU to create multilateral initiatives to deal with the Iranian nuclear program’. This conclusion was supported by real life developments such as the nuclear deal between Iran and the P5+1, which was concluded with the active involvement of Russia and China in the P5+1 block against Iran’s gaining nuclear weapons capabilities.

Thus, the analyses from 2005 to 2007 showed that the stakeholders’ interests regarding the Iranian nuclear issue were not likely to be reconciled in the short run and the only options for a resolution from the US perspective included economic, political or military coercion. In the following years, the world indeed witnessed further escalation of the crisis and expansion of unilateral and multilateral sanctions. The relative de-escalation started only after the 2013 initiation of secretive talks between the P5+1 countries and Iran and continued until 2015 when a nuclear deal was reached[65]. However, the latter developments occurred only after some important actors as well as political settings on both the US and Iranian sides were changed

6. Concluding Remarks

A major advantage of using this model for international conflict issues is that it allows for analysis of strategic moves by actors. An examination of such moves can lead to important policy recommendations. This simulation concludes, for example, that getting the support of Russia and China are the most crucial steps in dealing with Iran’s nuclear program, thus demonstrating the importance of a multilateral approach to the issue of Iran’s nuclear program. Iran could probably not resist extreme international isolation in the event that Russia and China join the US and the EU. But when the EU and the US are balanced by Russia and China, Iran’s bargaining power increases.

One shortcoming of the model is its imprecision in predicting the exact timing of the decisions made. Also, the model does not provide any information on how long this outcome will be stable. Therefore, many studies using this model have repeated their simulations over time with new data (preferably every six months) to control for changes in the bargaining conditions and external shocks, or they have developed alternative (counterfactual) scenarios.[66]

The state of graduate methods training in IR field in Turkey is, sadly, rather embarrassing. Most PhD programs do not offer basic methods seminars. I believe high quality scholarship can only be produced if scholars test explicitly stated hypotheses with replicable methods and original data in either qualitative or quantitative manner. In the long-run, we, as the Turkish IR community, have to resolve this issue by introducing basic and advanced methods training for the next generation of researchers. In the short-run, for current students, I suggest they reach out to ‘sister disciplines’ such as economics, psychology or sociology and take their methods training during their graduate studies as a quick solution to this problem. All three disciplines offer more advanced methods training than do IR or political science. The methodological skills gained in these courses will help students significantly in their projects.

Abdollahian, Mark, Michael Baranek, Brian Efird, and Jacek Kugler. “Senturion: Predictive Political Simulation Model.” In Defense and Technology Paper 32. Washington D.C.: Center for Technology and National Security Policy, National Defense University, 2006.

Abdollahian, Mark Andrew, and Jacek Kugler. “Unrevealing the Ties that Divide: Russian Political Succession.” International Interactions 23, no. 3–4 (1997): 267–81.

Banks, J.S. “Equilibrium Behavior in Crisis Bargaining Games.” American Journal of Political Science 34 (1990): 599–614.

Black, D. The Theory of Committees and Elections. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1958.

Brams, Steven. Theory of Moves. Cambridge [England]; New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce. “A Decision Making Model: Its Structure and Form.” International Interactions 23 (1997): 235–66.

———. Predicting Politics. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2002.

———. Principles of International Politics: People's Power, Preferences and Perceptions. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2003.

———. The War Trap. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, and David Lalman. War and Reason. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, David Newman, and Alvin Rabushka. Forecasting Political Events: The Future of Hong Kong. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, and Frans Stokman. European Community Decision Making: Models, Applications, and Comparisons. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994.

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, Rose McDermott, and Emily Cope. “The Expected Prospects for Peace in Northern Ireland.” International Interactions 27, no. 2 (2001): 129–67.

Cooper, Helene. “U.S. Weighing Terrorist Label for Iran Guards.” The New York Times, August 15, 2007.

Cooper, Helene, and David E. Sanger. "U.S. Annoyed by U.N. Report on Iran and Uranium, Hopes to Use It to Widen Sanctions." The New York Times, May 24 2007.

Cooper, Helene, and Nazila Fathi. “Terrorist Label for Iran Guard Reflects U.S. Impatience with U.N.” The New York Times, August 16, 2007.

Cordesman, Anthony H. Iran's Developing Military Capabilities. Washington, D.C.: CSIS Press, 2005.

Ellsberg, Daniel. “Risk, Ambiguity, and the Savage Axioms.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 77, no. 2 (1963): 336–42.

Feder, Stanley. “Factions and Policon: New Ways to Analyze Politics.” In Inside Cia’s Private World, edited by H. Bradford Westfield, 274–92. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

Feng, Yi. “Economic Reforms in China: Logic and Dynamism.” International Interactions 23, no. 3–4 (1997): 315–32.

Friedman, Francine, and Ismene Gizelis. “Fighting in Bosnia: An Expected Utility Evaluation of Possible Settlements.” International Interactions 23, no. 3–4 (1997): 351–65.

Fuchs, Doris Andrea, Jacek Kugler, and Harry Pachon. "Nafta: From Congressional Passage to Implementation Woes." International Interactions 23, no. 3–4 (1997): 299–314.

IAEA. “Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).” http://www.iaea.org/Publications/Documents/Treaties/npt.html.

Isidore, Chris. "Will Iran Dispute Push Oil to $130?" CNN, http://money.cnn.com/2006/02/07/news/international/iran_oil/index.htm.

James, Patrick, and Michael Lusztig. “Quebec’s Economic and Political Future with North America.” International Interactions 23, no. 3–4 (1997): 283–98.

James, Patrick, and Özgür Özdamar. The United States and North Korea: Avoiding a Worst-Case Scenario. Edited by Ralph Carter. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2004.

Kugler, Jacek, and Yi Feng. “Foreword.” International Interactions 23, no. 3–4 (1997): 233–34.

Kugler, Yacek, Birol Yeşilada, and Brian Effird. “The Political Future of Afghanistan and Its Implications for US Policy.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 20, no. 1 (2003): 43–71.

Martin, Lisa. Coercive Cooperation: Explaining Multilateral Economic Sanctions. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1992.

Nicholson, Michael. “Formal Methods in International Relations.” In Millennial Reflections on International Studies, edited by Michael Brecher and Frank P. Harvey, 345–60. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004.

Nuclear Threat Initiative. “Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant (BNPP).” http://www.nti.org/learn/facilities/184/.

“Ongoing U.S. Efforts to Curb Iran's Nuclear Program.” The American Journal of International Law 100, no. 2 (2006): 480–85.

Organski, A.F.K., and Ellen Lust-Okar. “The Tug of War over the Status of Jerusalem: Leaders, Strategies and Outcomes.” International Interactions 23, no. 3–4 (1997): 333–50.

Özcan, Nihat Ali. “İran Sorununun Geleceği: Senaryolar, Bölgesel Etkiler Ve Türkiye'ye Öneriler.” TEPAV Orta Doğu Çalışmaları Raporu 1, Ankara, 2006.

Özcan, Nihat Ali, and Özgür Özdamar. “Uneasy Neighbors: Turkish-Iranian Relations since the 1979 Islamic Revolution.” Middle East Policy 17, no.3 (Fall 2010): 101–17.

———. “Iran’s Nuclear Program and Future of US-Iranian Relations.” Middle East Policy 16, no. 1 (2009): 121–33.

Özdamar, Özgür. “Contributions of Game Theory to International Relations Literature.” [in Turkish] Uluslararası İlişkiler 4, no. 15 (2007): 33–66.

Özdamar, Özgür, and Sercan Canbolat. “Understanding New Middle Eastern Leadership: An Operational Code Approach.” Political Research Quarterly (2017). doi: 10.1177/1065912917721744.

Ray, J. L. and Bruce Russett. “The Future as Arbiter of Theoretical Controversies: Predictions, Explanations, and the End of the Cold War.” British Journal of Political Science 26, no. 4 (1996): 441–70.

Russett, Bruce M. “The Calculus of Deterrence.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 7, no. 2 (1963): 97–109.

Sahimi, Mohammed. “Iran’s Nuclear Program: Part 1: Its History.” Payvand, October 2, 2003. http://www.payvand.com/news/03/oct/1015.html.

Schelling, Thomas. The Strategy of Conflict. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960.

Snider, Lewis W., and Jason E. Strakes. “Modeling Middle East Security: A Formal Assesment of Regional Responses to the Iraq War.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 23 (2006): 211–26.

Stokman, Frans, and Robert Thomson. “Winners and Losers in the European Union.” European Union Politics 5, no. 1 (2004): 5–23.

UN Security Council. Resolution 1737. S/RES/1737 (December 23, 2006). http://www.iaea.org/NewsCenter/Focus/IaeaIran/unsc_res1737-2006.pdf.

UN Security Council Resolution 1747. S/RES/1747 (March 24, 2007). http://www.iaea.org/NewsCenter/Focus/IaeaIran/unsc_res1747-2007.pdf.

von Neumann, John, and Oskar Morgenstern. Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1944.