Levent Kırval

İstanbul Technical University

Arda Özkan

Ankara University

The oceans and seas cover 72% of the Earth’s surface, and 85% of global trade is done by maritime transportation. Moreover, 40% of the world’s population lives on or near coastlines. Also, the oceans play a crucial role in Earth’s biosphere. Recently, by desalination techniques, the seas have become a potable water resource. Therefore, one can say that the oceans and seas are indispensable for mankind. However, international disputes and collaboration efforts between states regarding the seas are not widely studied by scholars of international relations (IR). This can be referred to as sea blindness, and it may be defined as an inability to appreciate the importance of seas and naval power, particularly with regards to strategic security and economic prosperity. A country with sea blindness is not aware of maritime supremacy as an important foreign policy tool. Similarly, IR scholars mostly focus on land conflicts and not on sea issues when they study international politics. This is particularly true in Turkish IR literature as issues on land are again the focus areas for Turkish scholars. In this context, this article makes an analysis of the articles in peer-reviewed journals and books published by well-known publishers in Turkey, providing statistics about the issues covered. Also, for comparison, major political science and IR journals published abroad are analysed with regards to publications related to the seas. This statistical analysis elucidates whether there is sea blindness in Turkish IR literature. The number of articles and books that cover the seas as crucial study areas of IR in Turkey, as well as their broad focus areas and perspectives, are revealed by this study.

1. Introduction

The seas have played a key role in the scientific, cultural, and civilizational interaction between states. As the seas are crucial for wealth generation and geopolitical dominance, states have invested in technology and seamanship to master the seas and make use of the opportunities that the seas present. However, in many academic circles, the importance of the seas has not been studied extensively, a circumstance which can be referred to as sea blindness.[1] The concept of sea blindness can be defined as a general ignorance and failure to appreciate the importance of the maritime domain by the general public, policy makers, governors and scholars. Surely, it is time for the discipline of IR to pay more attention to the issues of maritime supremacy in foreign policy-making. The current literature only analyses these issues in terms of particular geographic hot spots and the management of specific threats, such as political disputes in the Arctic or the South China Sea, maritime piracy in East Africa, human trafficking in the Mediterranean or organized crime in West Africa.[2]

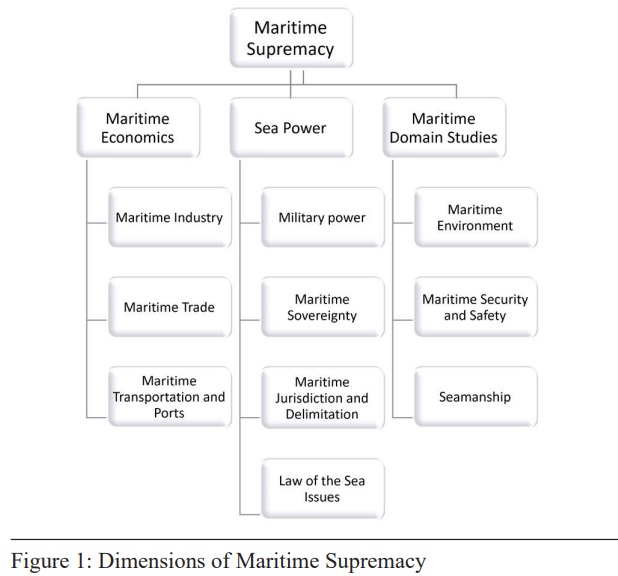

On the other hand, maritime supremacy essentially covers three basic areas. These are maritime economics, sea power and maritime domain studies. Maritime economics refers to a broad field that includes the commercial relations of humanity with the seas. In addition to military capabilities, maritime economics includes activities such as maritime industry, maritime transportation, maritime trade, port and marina management, as well as insurance and fishing.[3] Sea power is related to military/naval capabilities. In particular, it includes vehicles such as ships, submarines and the infrastructure (such as naval bases) within which they operate. The personnel who equip these vehicles and infrastructures also form an important part of sea power. At the same time, maritime jurisdiction areas and sovereignty issues are among the subjects studied within the framework of sea power. Sea power also includes military power, maritime sovereignty, maritime jurisdiction and delimitation, and law of the sea. Maritime domain studies, on the other hand, comprises areas such as the marine environment, protection of the seas and marine life, maritime safety/security and seamanship. Broadly, the aim of reaching safe (navigational safety), secure (free of crimes) and clean seas is the main study focus of this subject area.

Today, maritime supremacy in foreign policy-making is exercised by the states that have a broader vision of the seas. Sea blindness, on the other hand, is exhibited by states that consider their singular military and security interests as maritime supremacy mostly due to the advantages provided by their geopolitical position. However, these constitute only the sea power (security/defence) element of maritime supremacy. In addition to this, the other two elements, maritime economics and maritime domain studies, include studies in different disciplines such as maritime logistics, maritime industry, marine insurance, international trade, protection of the marine environment, and law of the sea. Yet, the scholarly analyses are mostly centred on the military and security dimensions of maritime studies in Turkish IR literature. As long as the lack of awareness about maritime economics and the maritime domain remains present, sea blindness will always be mentioned with regard to Turkish IR literature. In addition, maritime publications in Turkish IR literature are made periodically within the framework of maritime disputes encountered in foreign policy (such as the Eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean maritime jurisdiction area disputes, Montreux and the Straits issue). Publications on establishing maritime supremacy with a broader vision and, for instance, Turkey’s potential of becoming a maritime power (using maritime economics, sea power and maritime domain studies) are very few.

Furthermore, the five sea basins surrounding the country, namely the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea are very important for Turkey. The alternatives and opportunities offered by this complex geography to Turkey are so rich and diverse that they cannot be ignored. Turkey perpetuates a struggle for existence in these regions and sub-regions that differ economically, politically, religiously, culturally and ethnically.[4] Turkey’s foreign policy is implemented with the aim to become a dominant actor in these five basins. However, with regard to Turkish foreign policy on these sea basins, maritime supremacy is again understood as only a security/defence phenomenon. Research published in Turkish journals and publishing houses also follows this limited Turkish foreign policy perspective. In this study, we have thematically examined the concept of maritime supremacy, which we have chosen as our main subject, with both its three dimensions and ten key concepts related to it and at the scale of the five sea basins around Turkey. In this context, we examined the articles of journals and the books/chapters published by the publishing houses as main parameters.

Therefore, the main research question of this study is whether there is sea blindness in Turkish IR literature. We try to determine whether there is sea blindness in Turkish IR literature by comparing both Turkish and foreign publications. The number of scholars that analyse the importance of the seas for foreign policy formation is also limited at the global level, although it is not as few as the number of Turkish scholars who do so. In this regard, studies of several scholars who focus on the seas in political science and IR literature will be analysed in the following pages. Subsequently, a statistical analysis of Turkish and global IR literature concerning sea blindness will be provided. This analysis will show the missing maritime dimension in the IR discipline.

2. Importance of the Seas for Mankind

The seas have shaped the welfare level, security perception, social behaviour and foreign policy of states for centuries. Moreover, maritime industry is an important element of the economies of states as a means of communication with the world. While the strategic dimension of maritime supremacy is regularly underlined in IR literature, maritime economics and maritime domain studies, which are inseparable components of maritime supremacy, are less emphasized. In this context, it can be said that maritime supremacy is explained only with regard to its security/defence dimension.

When you ask people what they know about shipping or how much is traded by sea, they will most likely comment on several states’ naval or military capabilities. But one should not forget that we are still heavily dependent on the global trading system based on shipping. That said, maritime domain explanations are dominated solely by the security/defence lenses.[5] In fact, most of the products we buy reach us by maritime trade. Considering that 85% of global trade is carried out by the maritime sector, sea blindness should not be present given such a huge industry.[6] However, the seas are mostly analysed in the context of security/defence, particularly in IR literature, and this is surely a major shortcoming.

Today, maritime trade and transportation is the backbone of global capitalism and global trade, which includes raw materials, final industrial products, and hydrocarbons. More than 100,000 ships sail in the world’s seas and rivers, most of which are commercial fleets. As maritime transportation is the cheapest and most efficient mode of all transportation alternatives, it has played a crucial role in the development of the modern international system based on free trade after the Second World War. Due to the huge transportation capacity of ships, the price of a unit of transportation (i.e., a container) is extremely cheap in terms of shipping costs. Also, due to the right of free navigation in international waters, maritime transportation is performed freely at the global level.[7] The merchant fleets of the world have grown in ship numbers and tonnage particularly in the last 50–60 years. Several international laws and regulations have been enacted, and international organisations have also been formed (such as the United Nations International Maritime Organisation, or IMO) to ensure the security of international waters.

Undoubtedly, for economic development, international trade is essential, and maritime transportation is the main catalyst. The ports and merchant fleets of states are the most critical infrastructures for international trade. Generally, economic development is clearly visible in port cities, and unemployment is not a major problem in such areas. With globalisation, the importance of maritime transportation (both freight and passenger) has further increased. As large amounts of cargo can be transported via ships safely, reliably, and at a low cost, maritime transportation of products is the most preferred method of transportation.[8]

In addition to being important for global capitalism and global trade, the seas are also crucial for defence of the countries. For geopolitical dominance and supremacy, control of the seas by powerful navies is also extremely important. Approximately 5,000 naval ships sail in the world’s oceans and rivers. Furthermore, cooperation between states is also crucial for safe and secure seas. In this context, maritime domain awareness is critical. This concept is defined by the IMO[9] as the effective understanding of anything associated with the maritime domain that could impact economy, safety, security and the environment.[10] For this purpose, states are putting several agreements into effect to establish organizations in the international arena, especially focusing on maritime transportation, with the most important one being the IMO. Undoubtedly, countries should coordinate with each other, sharing information to ensure maritime security.

A state’s position with regard to the seas is another aspect that affects its political and economic power. If a state has a coast that connects to the world’s oceans, it sits in an advantageous position. Landlocked countries lie in a more disadvantageous position when it comes to international trade and geostrategic dominance. History shows that landlocked states face wars more frequently. In contrast, states that have a connection to the world’s oceans practice global trade more prolifically and are in a better position for economic development. Also, civilisations have prospered in coastal cities where transportation and cultural interactions between different peoples of that geography have been present. On the other hand, island states have some advantages in international relations as they can protect their lands from foreign attacks by powerful navies. As an exemplary case, the UK is a traditional maritime power. It holds the title of the starting site for industrialisation.[11] Its maritime prowess surely played a key role in this development.

Undoubtedly, sea power is crucial during times of both peace and war. States that wish to achieve an important position in world politics invest in their navy. Also, sea power has the important characteristic of deterrence in diplomacy. The concept of gunboat diplomacy is used for visible displays of naval power, implying or constituting a direct threat of warfare if the terms are not agreeable to the superior force in international politics.[12] With gunboat diplomacy, states aim not only to gain maximum profit from the seas and to impose a certain political view, but also to realize the desired attitudes. In fact, gunboat diplomacy is a show of force with warships.[13] To achieve such sea power, a state’s technological competencies and naval arsenal should be developed.

Starting in the 20th century, states that transport goods via land, a highly risky and costly method, have declined economically. On the contrary, states that trade freely via the seas have economically prospered. Such states have mastered a liberal economy and have supported free trade instead of mercantilism. The UK, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, Japan and the USA can be given as examples of such states. They purchase raw materials cheaply from land-based states, process them to make industrial products and sell these final products to other states. By trading internationally mostly via maritime transportation, these states have prospered economically.[14]

As can be comprehended from the discussion above, the seas clearly play a key role in states’ foreign policy decisions and opportunities. For any state, it is prudent to establish dominance in the seas in order to pursue an effective foreign policy. And for this to happen, besides sea power, states should seek maritime supremacy, especially in terms of maritime economics and maritime domain studies. The most prominent maritime powers, such as the UK, the USA, the Netherlands, Spain and Portugal, have reached that level historically by pursuing such a maritime supremacy perspective.

However, studies about the seas are rather limited in the IR discipline, and this limited attention toward maritime issues affects the breadth of IR discussions. That said, although limited in number, several scholars have still underlined the importance of the seas in their studies. In particular, the competition between sea and land powers has been an important issue in international politics for IR scholars. In this context, the limited scholarly analyses in IR about the seas will be summarized in the following pages.

3.Sea Blindness and Utilisation of the Seas in IR: Examples from the Literature

The seas are important factors of geopolitics, and they are also useful for defence. Land powers and naval powers have traditionally been in conflict with each other throughout history. In political science and IR literature, several scholars have analysed maritime or oceanic civilizations (thalassocracies) in opposition to continental Eurasian civilizations (tellucracies). The terms thalassocracy and tellucracy, introduced by Schmitt (1950), originate from the terms thalassa (sea) in Greek and telluris (earth) in Latin.[15] In Greek mythology, thalassa was the primeval spirit of the sea, whose name may be of pre-Greek origin. Telluris means earth in general, and ground, land or country in particular cases.

More recently, the Russian strategist Alexandr Dugin used this conceptualisation in his works. For him, thalassocracies (also referred to as Atlanticist) are represented by the United Kingdom and the United States, whereas Russia and Germany are typical tellucracies (also referred to as Eurasian). Thalassocracies underline the importance of markets. Because of their geographical location, they have power to promote trade. Individual freedoms and human rights in these countries are outcomes of their commercialism. On the contrary, tellucracies are agriculture- and military-oriented, and they are authoritarian.[16] In his analyses, Dugin favours tellucracies and considers Russia as a prime example of one. These ideas are derived from the theories of Western European geopoliticians such as Friedrich Ratzel, Rudolf Kjellen, Halford John Mackinder and Karl Haushofer.[17]

In The History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides (generally thought of as the father of Realism) tells the story of the struggle between Athens and Sparta.[18] In this ancient work, one can see the importance of naval power as it had an important role in the Peloponnesian War. The conflict was between Athens, a maritime power, and the preeminent land power of the day, Sparta. Athens’ superior fleet and ability to protect vital supply routes allowed it to endure during this war. Although Athens ultimately lost the war, its fleet enabled it to maintain its empire and retain a vital lifeline to its colonies and vassals that helped it to endure sieges. Furthermore, Athens’ eventual defeat came at the hands of the Spartan fleet. During the war, the Spartans not only capitalized on Athens’ many mistakes but importantly gathered their own fleet under Lysander, who went on to defeat and later capture the Athenian navy, thus concluding the war in Sparta’s favour.

In his seminal book Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes used the Leviathan, a mythical creature with the form of a Sea Serpent (Sea Monster), which greatly influenced IR literature.[19] That said, in this well-known book, this mythical creature is used to represent state power mostly on land. According to Judaism, Behemoth, a beast on Earth from the biblical Book of Job (Hebrew Bible), and Leviathan (again from the Hebrew Bible, Sea Monster) are destined to fight with each other until doomsday. However, their depiction in Hobbes’ work, and particularly the justification of state power by the protection of individuals by the Leviathan, are limited to political discussions on land.

In The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean, David Abulafia underlines the importance of naval power, particularly for the societies of the Mediterranean.[20] In his work, Abulafia illustrates how Mediterranean societies become sea powers in order to dominate the region. For Abulafia, Mediterranean history is world history, and sea power is vital for any state to dominate international politics.

In his work, Histories of the Sea (Histoires de la Mer), Jacques Attali shows that civilisations have prospered on the coasts of the Mediterranean. By using the capabilities that the sea presents, these civilisations communicate with each other and economically prosper as a result.[21] In this work, Attali shows how civilizations have become dominant powers in their regions by using the seas.

Alfred Thayer Mahan underlines the importance of sea power for geopolitical hegemony. Mahan believes that there is a strong link between a country’s political power and the sea. Use of the sea in trade and control in war in particular is of utmost importance for Mahan.[22] Mahan focuses on strategic locations such as canals, coaling stations, choke points, and states for which control of these locations is crucial for political power. Also, the economic use of the seas is crucial for Mahan, and during times of peace, he believes that states should increase their production and shipping capacities and acquire overseas possessions. Mahan highlights the importance of a transnational coalition acting in support of a multinational system of free trade.

Another important scholar on the topic of sea power is Julian Corbett. Corbett does not place as much emphasis on fleet battle as Mahan does. He concentrates on the importance of Sea Lines of Communication instead of battle prowess. To gain control of the Sea Lines of Communication, destruction or capture of enemy warships and merchants, or conducting a naval blockade, are main options for Corbett.[23]

George Modelski also underlines the value of sea power.[24] For Modelski, only sea powers can respond to global problems and construct a global political system as they have open societies and prosperous economies. For Modelski, the challengers to these powers are regional powers with substantial land armies, as well as more reclusive societies and economies. Modelski also argues that the rise and fall of world powers is parallel to the rise and decline of industrial and commercial sectors in the global economy. Modelski refers to these as Long Cycles, which shows a pattern of regularity in world politics. For Modelski, there is a regularity of transition of power between major world powers, all sea powers, such as the Dutch Republic, Portugal, the United States and the United Kingdom.[25]

Immanuel Wallerstein also utilizes the concept of maritime supremacy in his works. In his famous world-systems theory, Wallerstein tells the story of how capitalism changed the world. World-systems theory underlines an inter-regional and transnational division of labour, which divides the world into core states, semi-periphery states, and periphery states. Core states have capital-intensive production, higher skill, and the rest of the world have labour-intensive production, low-skill, and they work for the extraction of raw materials. Yet, the system has dynamic characteristics. As a result of revolutions in transport technology, individual states can gain or lose their core (semi-periphery, periphery) status over time. Certain states become world hegemonies for a certain period of time. During the last few centuries, as the world-system has prospered economically and extended geographically, this hegemony has passed from the Netherlands to the US and the UK.[26] All of these states have been important sea powers and active maritime traders, which has helped them to reach this status. In world-systems theory Wallerstein underlines the importance of shipping and maritime trade, as well as the control of shipping routes, for rising from the periphery to the core.

Halford John Mackinder also asserts the significance of sea power on international relations. Mackinder is considered the founding father of both geopolitics and geostrategy. For Mackinder, the Earth is divisible into:

- The World-Island, the interlinked continents of Europe, Asia and Africa (Afro-Eurasia). This is the biggest, most crowded, and wealthiest of all possible land combinations.

- The offshore islands, inclusive of the British Isles and the islands of Japan.

- The outlying islands, inclusive of the continents of North America, South America, and Oceania.

The Heartland stands at the centre of the World-Island.[27] In 1919, Mackinder summarised his theory as:[28]

“Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World-Island commands the world.”

The power that controls the World-Island would control more than half of the world’s resources. The Heartland’s central position and size makes it the key to controlling the World-Island.

Mackinder tried to warn the UK that its dependence on sea power would become a weakness as improved land transport would open the Heartland up for invasion and/or industrialisation.[31] Although he warns Britain not to rely solely on sea power, one can still clearly see a land-sea dichotomy in his analyses. He underlines the importance of control over the Heartland and thus warns Atlantic powers (particularly Britain) that their maritime dominance at the global level may not be enough to control the whole globe.

Nicholas John Spykman’s work is similar to Mackinder’s, and it is based on the unity of the world seas and unity of world politics. However, Spykman also extends it to include unity of the airspace. Hence, Spykman underlines the importance of the air force for any country. For Spykman, maritime mobility makes “the overseas empire” a possibility. Spykman divides the world into:

- the Heartland

- the Rimland (same as Mackinder’s “inner or marginal crescent”)

- the Offshore Islands & Continents (similar to Mackinder’s “outer or insular crescent”)

“The Rimland” is a term particularly used by Spykman. His perspective is that the most strategic areas in the world are the densely populated eastern, western and southern edges of the Eurasian continent. Spykman criticises Mackinder for underlining the importance of the Heartland and for his preference for land power over sea power.[32] According to Spykman:[33]

“Who controls the Rimland rules Eurasia, who rules Eurasia controls the destinies of the world.”

Another important scholar who utilises maritime concepts in his IR analyses is John Mearsheimer. Mearsheimer is most known for his theory of ‘offensive realism’. According to this theory, the great powers aim for regional hegemony in an anarchic international system. For Mearsheimer, a state’s power is related to the strength of its military. For him, land force is the dominant military power in the modern era, and large bodies of water (oceans) limit the capabilities of land armies (he refers to this as the stopping power of water). Hence, because of the oceans, no country can become a world hegemon. As a result, the world is divided into different areas where there are major regional powers.[35]

Therefore, for Mearsheimer, the US should try to become the hegemon of the Western Hemisphere only. Also, it should stop the rise of a similar hegemon in the Eastern Hemisphere. Hence, the United States is an offshore-balancer. It may only balance the rise of a Eurasian hegemon. Offshore-balancing highlights withdrawal from onshore positions and underlines offshore capabilities on the three key geopolitical regions of the world: Europe, Northeast Asia and the Persian Gulf.[36]

As another important scholar of IR, Christopher Layne criticizes Mearsheimer’s reasoning. As Layne states, “apparently water stops the US from imposing its powers on others in distant regions, but it does not stop them from threatening American primacy in the Western Hemisphere”.[37] Hence, Layne questions the ability of the oceans to constrain power-maximising states into status-quo powers.

Barry Buzan and Ole Wæver also underline the importance of the seas in their analyses. These scholars developed Regional Security Complex Theory, in which they argue that international security should be analysed from a regional perspective. Moreover, they argue that relations between states (and other actors) show regular, geographically-clustered patterns. Regional security complexes are, by nature, geographical and consist of neighbouring actors that are insulated from one another by natural barriers such as deserts, mountain ranges and oceans.[38]

Jack Levy and William Thompson, on the other hand, argue that leading sea powers do not have the capability, nor the incentive, to threaten the domestic political order of other major powers.[39] Thus, for them, sea powers are non-threatening actors in international relations. The real decisive actors of global politics are land powers and regional actors in this perspective.

In the analyses of the above-mentioned theorists, the seas hold a pivotal position in discussions of dominance in IR. In some of the examined works, a land-sea dichotomy is also visible. Thus, for various scholars of IR, the competition between land-based and sea-based powers is an important issue in IR. That said, the number of scholars who underline the importance of the seas for global dominance is still marginal. Only few of the studies summarised in the previous pages could be given as examples. In some of these studies, maritime issues are implied, but remain overshadowed by other security topics. There is a fairly mainstream discussion on American grand strategy by IR luminaries (like Mearsheimer and his critics) that is premised on maritime concepts, but again with a very limited and particular focus on the military aspects of naval power. The whole discussion on the (alleged) stopping power of water and offshore balancing further reinforces this article’s main argument that maritime topics are either neglected or are only there as an afterthought to national security.

The two important aspects of maritime supremacy (maritime economics and maritime domain studies) are neglected by most of these scholars. Therefore, one can say that sea blindness is a major deficiency within the IR discipline. Similarly, sea blindness has been present in Turkey up until the last couple of years. The rise in sea-related publications in recent years is a result of disputes with Greece and the Greek Cypriot Administration of Southern Cyprus (GCASC). Particularly, the defence/security dimension of maritime supremacy is merely analysed in Turkish IR literature. Given these observations, an analysis of Turkish and global IR literature concerning sea blindness will be made in the following pages.

4. Sea Blindness and Turkish IR Literature

Maritime supremacy and its subfields, namely, maritime economics (inclusive of merchant fleet ports and shipyards), sea power (security/defence policy) and maritime domain studies (protection of the seas and marine life) have been shown to bolster states seeking power in IR. Of these subfields, maritime economics is a broader term that includes all the marine-and maritime-related economic sectors in a country. Here, human resources and the general public’s awareness of the maritime domain and economic production in these sectors is of utmost importance. Maritime economics also includes maritime industry (trade, transportation and ports). Sea power is related to the military capabilities at sea, infrastructure and naval capabilities. Particularly, the number of ships (the navy) and the related infrastructure (such as naval bases) is crucial. It includes military/naval power, maritime sovereignty and maritime jurisdiction and delimitation areas. Maritime domain studies include maritime environment, maritime safety/security and seamanship. Safe, secure and clean seas are the main targets of policy-makers in this domain.

As a remedy for sea blindness, the general public should also be included in the broad maritime policy decisions of the state. Social activities such as sailing, scuba diving, building model ships, swimming, amateur fishing, and the like should be organised to promote a positive culture around the sea. Coastal areas should be planned so that the seas are easily accessible by the public for recreational activities. Maritime trade and transportation, sea logistics, shipbuilding, fishing, marine insurance and port management zones should be developed to get a bigger share from the global capitalist production system. The relevant high schools and departments or faculties of universities should be established so that the youth is aware of the importance of the seas for economic and political development of the country. With these strategies, the state and society can become more active in maritime economics, sea power and maritime domain studies, which helps move toward the broader political vision of becoming a global maritime power.

Quite contrarily, (and like the Turkish state and society in general) Turkish IR literature in maritime economics and maritime domain studies is limited to naval/military capabilities. The grand strategy of becoming a maritime power is left on the shoulders of military personnel. What’s necessary then is the development of civilian seamanship and sea culture in a country. A foreign policy acknowledging the importance of maritime supremacy based on maritime economics, sea power and maritime domain studies for global geostrategic and economic hegemony is lacking in Turkish foreign policy.

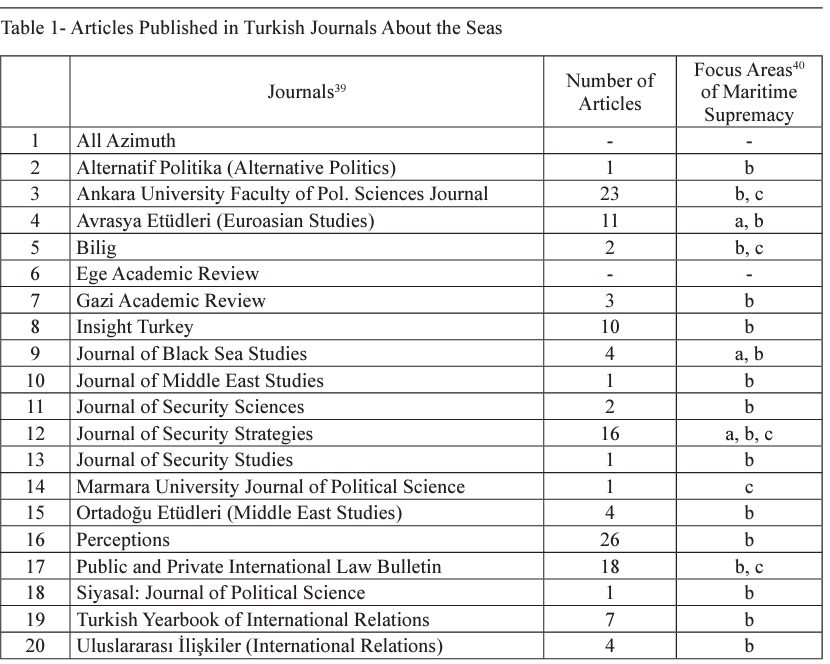

Publications in Turkish IR literature follow Turkish foreign policy and focus mostly on the defence/security dimension (sea power) of maritime supremacy. The parameters we use for both journals and published books identify maritime supremacy as a subject, with maritime economics, sea power and maritime domain studies as its subfields, and the five sea basins surrounding Turkey as a thematic area. (We have only looked at the Turkish publications designating the five sea basins as a thematic area.) In terms of years, the founding dates of the journals and publishing houses until 31 December 2021 are taken as a criterion. The concept of maritime supremacy is not limited to disputes over the delimitation of maritime jurisdiction areas (or law of the sea issues) or military/security power issues such as gunboat diplomacy. Maritime supremacy also includes maritime economics and maritime domain studies areas. In this context, one can see that sea blindness is present in Turkish IR literature by looking at Table 1, since most of the publications here are related with the military/security dimension of maritime supremacy. The authors of this manuscript have perused the articles published in twenty of the most well-known Turkish political science and IR journals about the seas and have found out the following results.

As can be seen in the table above, the number of articles published about the seas is rather limited in Turkey. Particularly, there is a tendency towards publishing material solely on the sea power dimension of maritime supremacy. Of the 20 Turkish journals we analysed to detect sea blindness, we have seen that 2 journals did not publish any articles on the seas. Only 3 of the remaining 18 journals have articles related to a-type,[42] and there are 5 journals that published about c-type.[43] Except for 1 journal (the Marmara University Journal of Political Science, which has only 1 publication related to c), almost all of them have b-type.[44] We think it is helpful to give some details in order to understand Table 1. For example, 20 articles are about b and 3 articles are about c in Ankara University Faculty of Political Sciences Journal, which has a total of 23 articles on the seas. In this journal, there are no articles related to a. In the journal Eurasian Studies, only 1 of the 11 articles is about a and the others are about b. When we look at the Journal of Security Strategies, we see a little more diversity. This journal, which has published 16 articles on the seas, has 11 articles about b, 3 articles about a and 2 articles about c. All aspects of maritime supremacy (all a, b, and c) have been published in this journal alone. The journal Perceptions, on the other hand, has 26 articles about the seas, but they are all about b. In this journal, articles mostly about Turkey's Aegean, Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea policies were published. Public and Private International Law Bulletin, a journal of international law, has published 17 articles. However, only 3 of them are related to c and the others are related to b. In this journal, there is no article about a.

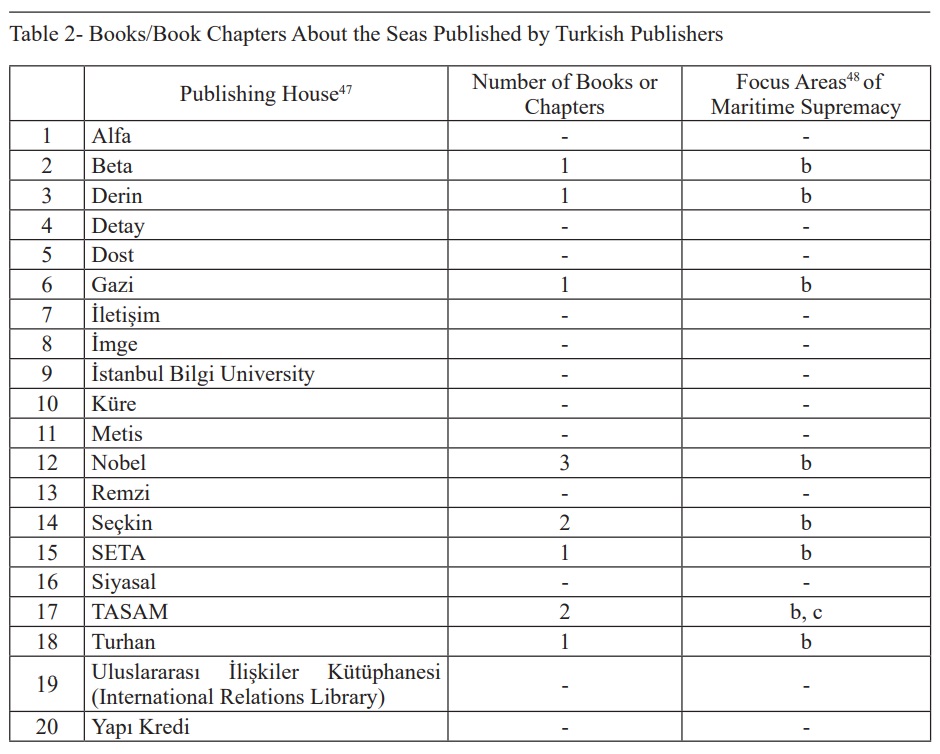

Similar observations can also be made about the books/book chapters published in Turkey. There are very limited publications on the maritime economics and maritime domain studies dimensions of maritime supremacy in Turkish books and book chapters. When we look at the 20 Turkish publishing houses in Table 2, we see that sea blindness continues to be a trend. Only 12 books from the 20 publishers we analysed are about the seas. And 11 of these are about b-type,[45] while only 1 is about c-type.[46] Almost all of the publications related to b are about the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean, and only one of them is about the Black Sea. Only TASAM has 1 book about c, and this is about the marine ecosystem. Looking at Table 2, we see that there is no publication about a[47] (on maritime economy), which is an important dimension of maritime supremacy.

When analysing international politics, global IR scholars generally base their studies on certain land areas. This is particularly true for the IR literature in Turkey. For Turkish scholars, of the three areas of sovereignty of a state (land, sea, air), the land area is prioritised, and the land conflicts are studied often. This situation is also similar in Turkish foreign policy. The decision-makers in Turkey mostly focus on the seas with regard to their security/defence. The importance of the seas for geopolitical dominance has only come up in Turkey due to the disputes with Greece and GCASC concerning the Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, particularly after the 2000s. Although the dispute with Greece over the Aegean dates back to the 1970s, the importance of the seas did not come to the forefront of debates within Turkish academic circles or in Turkish IR literature until the last couple of years.

Also, publications on the five sea basins around Turkey are rather limited in Turkish IR literature. Historically, the Eastern Mediterranean basin has been a very important geostrategic region that connects the East and the West. During the last couple of years, the seas have become a hot topic in Turkey due to disputes with Greece and the GCASC in the Eastern Mediterranean. Coupled with the hydrocarbon research activities in the region, supremacy has become a target for Turkish policy-makers. As can be seen from Tables 1 and 2, publications about the region only focus on sea power, which concerns disputes regarding maritime jurisdiction areas. In Turkish foreign policy, sea blindness continues to be a trend, and only very recently has the importance of the seas surrounding Turkey been comprehended.

Analyses of Turkey’s Black Sea policy are made by taking into account the different power centres that affect the politics of the region. In Turkish IR literature, strategic analyses are made about the Black Sea, examining aspects such as the geopolitical position of the Black Sea, the role and importance of the Black Sea in terms of Turkey’s regional and international security, and Turkey’s potential to become an important power within the Black Sea region as a coastal state.[50] Likewise, studies on the Turkish Straits, which are located on the exit route of the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, are generally related to issues concerning the law of the sea on the basis of the Montreux Convention, and to hard power issues such as geostrategic and power balances.[51] In the books/book chapters and articles published on the Black Sea and the Turkish Straits that unite the continents, only the naval/military force (sea power) element is discussed among the factors of maritime supremacy. Since there are almost no publications on maritime economics and maritime domain studies, one may conclude that sea blindness is prevalent in Turkish IR regarding the Black Sea and the Straits. As a matter of fact, maritime economics has become a fundamental dynamic that significantly affects the international system and security in these regions, which began to be referred to as the wide Black Sea basin in the post-Cold War period. Also, there is a growing need for studies on marine energy security and the maritime environment in these regions.

In the new geopolitical equation that emerged after the Soviet Union, the Caspian Sea is at the forefront of the places where both regional and non-regional power groups are most engaged in the struggle for influence. The most important feature of the Caspian is that it has the richest oil and natural gas deposits in the world. However, the fact that the status of the Caspian cannot be determined (is it a sea or a lake?) causes significant tensions between the littoral states, especially regarding the rich hydrocarbon reserves. Turkey sees this place as an energy transit area in terms of energy projects and pipeline routes in the Caspian.[52] The studies of Turkish IR scholars on the Caspian, who generally follow Turkish foreign policy, are mostly related to the delimitation of maritime jurisdiction areas, sovereignty rights established on natural resources, political problems between littoral states, energy companies operating in the Caspian basin, the effects of oil and natural gas trade on the global economy, importance of the resources in the Caspian for Turkey, maritime sovereignty and naval/military power. However, there is a need for publications in areas such as maritime economics, protection of the marine environment or management of the ports within the region.

Connecting the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean, the Red Sea is a crucial waterway for the world. The Red Sea and Suez Canal are very important geopolitically given their roles in energy transfer and maritime trade. States’ foreign policies in this region, their affairs with regional and global actors, and domestic political developments are affected by and also affect the Red Sea-oriented competition. On the other hand, The Persian Gulf, which has rich oil/natural gas deposits, is a gulf connected to the Indian Ocean in the region between southwest Iran and north of the Arabian Peninsula in the Middle East. One-third of the world’s oil production is carried out in the Persian Gulf and two-thirds of the world’s oil reserves are located in this region. In addition to oil wealth, natural gas is also abundant in states such as the UAE and Qatar.[53] Studies in Turkish IR literature are limited to political power struggles between the Red Sea and Persian Gulf littoral states. In both regions, we see a lack of research and a lack of interest in areas such as maritime economics and maritime domain studies, which are key factors for maritime supremacy. Thus, we have shown that sea blindness is also present in Turkish IR literature about these regions.

In addition to the five sea basins that are important for Turkey, the polar regions are seen as a new area of struggle within the scope of both economic investment opportunities and as a new maritime transport route. As a matter of fact, the Arctic and Antarctic regions are very important for global actors due to potential natural resources and the sovereignty struggles of states. Although the polar regions are difficult for human settlement due to the harsh climate conditions, they draw attention with the ample hydrocarbon reserves they contain.[54] In recent years, Turkish IR scholars have started to publish material on topics such as the delimitation of maritime jurisdictions on the poles, the sovereignty struggles between littoral states, and the policies of organizations such as the EU and NATO on the poles. However, studies on only one dimension of maritime supremacy (sea power) have again led to sea blindness with regard to these areas. On the other hand, some other studies are also published on the English Channel between France and the UK,[55] and the South China Sea, where there are disputes between China, Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia, Taiwan and Brunei on maritime jurisdiction areas. Yet, these studies are again mostly about continental shelf disputes, the EEZ, and security and defence issues. Turkish scholars have done very limited studies on areas such as marine environment policy, maritime economics, maritime transport policy or the South China Sea. Due to this situation, it is possible to say that sea blindness also exists for these regions.

In sum, despite being surrounded by five sea basins, Turkey has so far failed to develop a robust foreign policy based on attaining supremacy over its surrounding seas and expanding its international trade activities by means of maritime transportation, which necessitates the development of a strong merchant fleet. To the extent that the Turkish IR literature examines maritime issues, its area focus is sadly limited to defence/security issues, focusing primarily on a limited consideration of gunboat diplomacy and issues such as hydrocarbon research activities in the Eastern Mediterranean against Greece and the GCASC. A broad foreign policy based on maritime supremacy that includes maritime economics, sea power, and maritime domain studies is wanting in Turkish politics. Similarly, Turkish IR literature lacks a broad vision. Without such a strategy, it is anticipated that the limited maritime activities and policy-making in Turkey, as well as in the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean, are destined to be unsuccessful.

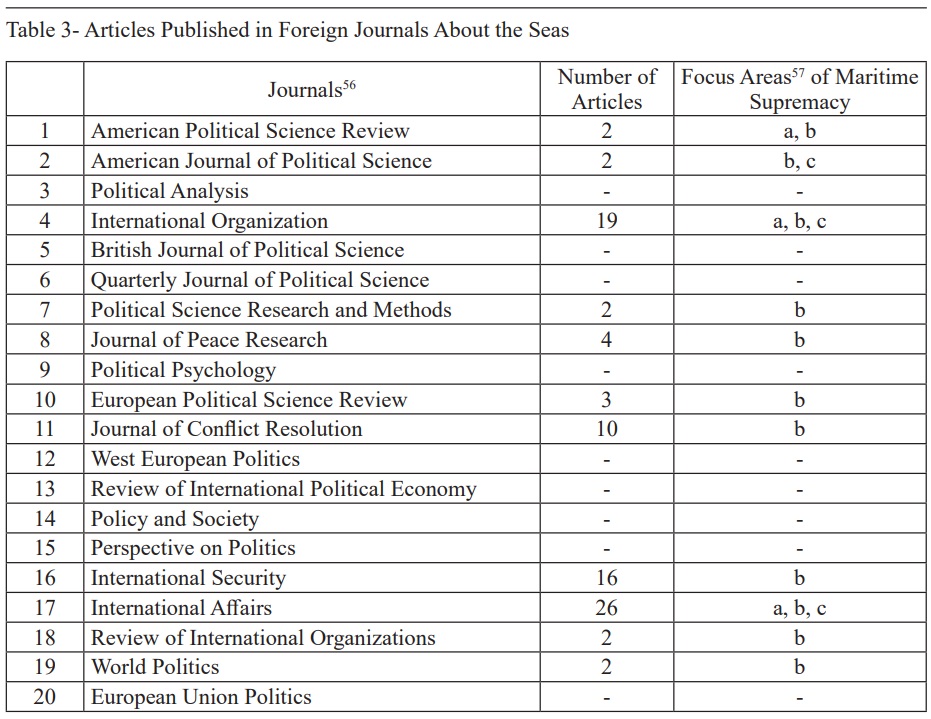

The analysis of the number of articles in Turkish journals and books/book chapters by Turkish publishers proves that there is sea blindness in Turkish IR literature. However, sea blindness is also a major problem in the broader IR discipline. That said, the number of articles that are published in foreign journals on the seas, especially about maritime economics and maritime domain studies, is much higher than the Turkish ones. The following table shows that European-Western and international scholars are aware of the importance of the seas for foreign policy-making. Table 3 is organised by the top 20 journals of the Scopus index on political science and IR.[56] As can be clearly seen here, the number of articles on the seas is much higher than the Turkish publications about maritime economics and maritime domain studies. However, this number is still not high enough to grasp the importance of the seas for world politics. Therefore, one may stipulate that sea blindness is also a major deficiency of the global IR discipline, but this is a topic that should be researched in another paper.

When we analyse Table 3, we see that 11 of the 20 foreign journals we examined have published articles about the seas. Only 2 of these journals (International Organization and International Affairs) had publications on a,[59] b[60] and c-type[61] articles. International Organization has published a total of 19 relevant publications, 7 of which are about a and b, with the remaining 5 being about c. International Affairs has published 5 articles about a and c, and 16 about b. There is even one article about sea blindness in this journal. This article has been categorised as c in our analysis, because it is more related to c.

As we can see from Table 3, maritime issues are not frequently studied in foreign journals either. They have been studied only in certain foreign journals with dimensions of a, b and c. This situation shows that there is partial sea blindness in foreign journals as well. However, when the articles in these journals are compared with Turkish IR literature, we can see that dimensions of a, b and c have been studied more in the foreign journals. Contrarily, only the dimension of a is studied frequently in Turkish IR literature. Therefore, we may conclude by saying that there is a lesser degree of sea blindness in global IR literature as compared to Turkish literature.

5. Conclusion

The five sea basins, a concept developed to describe Turkey’s sphere of influence, are regions that are frequently studied by Turkish IR scholars and are used to refer to the Mediterranean Sea, Red Sea, Persian Gulf, Caspian Sea and Black Sea. However, the publications made by Turkish scholars in these regions, which are important for Turkish foreign policy, are generally about sea power, or to be more precise, they are largely security- and defence-oriented. Moreover, when we look at the manuscripts published in refereed journals in the discipline of IR in Turkey, we see that there are not many articles on the other two important dimensions, namely maritime economics and maritime domain studies. On the other hand, books/book chapters published by the publishing houses are mostly written about the five sea basins, and again focus on sea power in international politics.

Whether we evaluate on a basin basis or with all dimensions of maritime supremacy included, we can say that sea blindness is present in Turkish IR literature because scholars do not focus on the two major dimensions of maritime supremacy (maritime economics and maritime domain studies), nor do they take into account all dimensions of maritime supremacy. Another point that should be noted is that the number of security/defence publications based on sea power are also low. Such publications in Turkish IR literature increase cyclically when Turkish foreign policy faces disputes in maritime jurisdiction areas (such as the Aegean or the Eastern Mediterranean). Of course, a similar situation exists in IR literature at the global level. IR and foreign policy analyses are generally made about the land area of states. However, it should be noted that such publications that focus on all dimensions of maritime supremacy are still more common globally when compared to Turkish IR literature.

Turkish IR literature lacks a broader vision about the seas and underestimates the importance of maritime supremacy for foreign policy-making. Indeed, the Ottoman Empire, Turkey’s predecessor, was a major sea power and controlled the seas of the Eastern Mediterranean for more than seven centuries. Modern Turkey should be similarly aware of the importance of the seas for foreign policy and should have a broader vision by prioritising maritime economics and maritime domain studies as key factors of maritime supremacy. Focusing solely on sea power is not enough to create a nation aware of the importance of the seas. And it should be stated that even this focus on sea power has flourished mostly as a result of the recent clashes with Greece and Greek Cypriots, caused by the ongoing dispute in recent decades about the sovereignty of the Aegean Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean. If not for this dispute, one can say that Turks would be relatively unaware of the importance of the seas. Therefore, it is clear that there is a need for ample publications in all areas of maritime supremacy in Turkish IR literature. In the future, it is expected that Turkish scholars will publish more articles and books/book chapters about these vital topics.

Abulafia, David. Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2013.

Amirbek, Aidarbek. “Soğuk Savaş sonrası Hazar’ın statüsü ve sınırlandırma sorunu: kıyıdaş Devletler’in yaklaşımları açısından analizi.” Karadeniz Araştırmaları 12, no. 46 (2016): 23–48.

Attali, Jacques. Histories de la Mer. Pluriel Publishers: Paris, 2018.

Aydın, Mustafa, and Çağrı Erhan, ed. Beş deniz havzasında Türkiye (Turkey in Five Sea-Basins). Ankara: Siyasal Yayınevi, Ankara, 2006.

Beasley, W. G. The Meiji Restoration. Stanford University Press: Stanford, 2018.

Boraz, Steven C. “Maritime Domain Awareness: Myths and Realities.” Naval War College Review 62, no. 3 (2009): 136–46.

Bueger, Christian. “From Dusk to Dawn? Maritime Domain Awareness in Southeast Asia.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 37, no. 2 (2015): 157–82.

Bueger, Christian, and Timothy Edmunds. “Beyond Sea Blindness: A New Agenda for Maritime Security Studies.” International Affairs 93, no. 6 (2017): 1293–31.

Buzan, Barry, and Ole Wæver. Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security (Cambridge Studies in International Relations). Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2003.

Byers, Michael. International Law and the Arctic. Cambridge University Press: United Kingdom, 2013.

Cable, James. “Gunboat Diplomacy: Political Applications of Limited Naval Force.” Chatto and Windus for the Institute for Strategic Studies: London, 1971.

Campling, Liam, and Alejandro Colas. Capitalism and the Sea: The Maritime Factor in the Making of the Modern World. Verso Press: London, 2021.

Corbett, Julian S. Some Principles of Maritime Strategy. Antony Rowe Ltd.: Eastbourne, 2009.

Cropsey, Seth. Seablindness: How Political Neglect Is Choking American Seapower and What to Do About It? Encounter Books: New York, 2017.

Crowl, Philip A. “Alfred Thayer Mahan: The Naval Historian.” In Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, edited by Peter Paret, Gordon A. Craig, and Felix Gilbert. Princeton University Press, 1986.

Denemark, Robert A., Jonathan Friedman, Barry K. Gills, and George Modelsk. World System History: The Social Science of Long-term Change. Routledge: New York, 2000.

Dugin, Aleksandr. The Foundations of Geopolitics: The Geopolitical Future of Russia. Arktogeja Publishers: Moscow, 1997.

Ekşi, Nuray. “Montreux Antlaşması uyarınca Boğazlardan geçen yabancı gemilerin haczi ve bu gemilere el konulması.” Public and Private International Law Bulletin 37, no. 1 (2017): 125–84.

Goodall, Thomas D. “Gunboat Diplomacy: Does It Have A Place In The 1990’s?” Global Security, 1991. Accessed by September 17, 2021. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1991/GTD.htm.

Grotius, Hugo. Mare Liberum. Lodewijk Elzevir Publishing House: Leuven, 1609.

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan. Penguin Books: London, 2017.

Khurana, Gurpreet S. “India’s Sea-blindness.” Indian Defence Review 24, no. 1 (2009) http://www.indiandefencereview.com/news/indias-sea-blindness/0/.

Kipgen, Nehginpao. “Asean and China in the South China Sea Disputes.” Asian Affairs 49, no. 3 (2018): 433–48.

Koçer, Gökhan. “Karadeniz’in güvenliği: uluslararası yapılanmalar ve Türkiye.” Gazi Akademik Bakış 1, no. 1 (2007): 195–217.

Layne, Christopher. “From Preponderance to Offshore Balancing: America’s Future Grand Strategy.” International Security 22, no. 1 (1997): 86–124 .

–––. “Offshore Balancing Revisited.” Washington Quarterly 25, no. 2 (2002): 233–48.

–––. “The Poster Child for Offensive Realism: America as a Global Hegemon.” Security Studies 12, no. 2 (2003): 120–64.

Levy, Jack S. and William R. Thompson. “Balancing on Land and at Sea: Do States Ally against the Leading Global Power?” International Security 35, no. 1 (2010): 7–43.

Lonsdale, David J.and Thomas M. Kane. Understanding Contemporary Strategy, 2nd Ed. Routledge, 2020.

Mackinder, Halford John. Democratic Ideals and Reality: A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction. National Defense University Press, 1996.

–––. “The Geographical Pivot of History.” The Geographical Journal 23, no. 4 (1904): 421–37.

Mahan, Alfred Thayer. The Influence of Sea Power upon the French Revolution and Empire, 1793-1812. Forgotten Books Publishers: London, 2012.

–––. The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660-1783. Little Brown and Co. Publishers: Boston, 1890.

Mearsheimer, John. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. W.W. Norton & Company: New York, 2001.

Merrils, John G. “The United Kingdom - France Continental Shelf Arbitration.” California Western International Law Journal 10, no. 2 (1980): 314–64.

Modelski, George, ed. World System History: The Social Science of Long-term Change. Routledge: New York, 2000.

Modelski, George, and Sylvia Modelski, eds. Documenting Global Leadership. Macmillan: London, 1988.

Modelski, George, and William Thompson. Leading Sectors and World Powers: The Co-evolution of Global Economics and Politics. University of South Carolina Press: Columbia, 1996.

Modelski, George, and William Thompson. Sea Power in Global Politics 1494-1993. Macmillan: London, 1988.

Moore, Barrington. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World. Beacon Press: New York, 1993.

Nagata, Yuzo. Studies on the Social and Economic History of the Ottoman Empire. Akademi Press: İstanbul, 1995.

Rothwell, Donald R. Law of the Sea. Edward Elgar Publishers: Chelthenham, 2013.

Schmitt, Carl. Der Nomos der Erde im Völkerrecht des Jus Publicum Europaeum. Greven Publishers: Cologne, 1950.

Sempa, Francis P. “Mackinder’s World.” American Diplomacy, February 2000. https://americandiplomacy.web.unc.edu.

Shlapentokh, Dmitry. Russia between East and West: Scholarly Debates on Eurasianism. Brill: Leiden, 2007.

Spykman, Nicholas John. America’s Strategy in World Politics: The United States and the Balance of Power. Routledge: London, 2007.

–––. The Geography of the Peace. Harcourt Brace & Co. Publishers: London, 1944.

Stopfort, Martin. Maritime Economics. Routledge: London, 2009.

Tanaka, Yoshifumi. The International Law of the Sea. 3rd Ed. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Penguin Books: London, 2000.

Trolle-Anderson, Rolph. “The Antarctic Scene: Legal and Political Facts.” In The Antarctic Treaty Regime: Law, Environment and Resources, edited by G. D. Triggs. Cambridge University Press: United Kingdom, 2008.

Tüysüzoğlu, Göktürk. “Kızıldeniz’e odaklanan güç mücadelesi: sebepler ve aktörler.” Ortadoğu Etütleri 11, no. 2 (2019): 324–67.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. The Modern World-System I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. University of California Press: Los Angeles, 2011.

–––. The Modern World-System II: Mercantilism and the Consolidation of the European World-Economy, 1600–1750. University of California Press: Los Angeles, 2011.

–––. The Modern World-System III: The Second Era of Great Expansion of the Capitalist World-Economy, 1730s–1840s. University of California Press: Los Angeles, 2011.

–––. The Modern World-System IV: Centrist Liberalism Triumphant, 1789–1914. University of California Press: Los Angeles, 2011.

–––. World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction. Duke University Press: London-Durham, 2004.