1. Introduction

Although terrorism was a research subject before the attacks on 11th of September 2001 (9/11), researchers have paid more attention to the discipline since then. With the more-recent Madrid, London, and Istanbul bombings, terrorism studies have gathered momentum and, as Shepherd says, entered the “golden age” of research. Moreover, many researchers have carried out seminal reviews on academic pieces of terrorism. One such scholar, Alex Schmid, has searched concepts, theories, databases, and literature. Silke has examined problems in terrorism studies, particularly from the methodological and conceptual perspectives. Another study, which is a successor to previous works, encompasses multiple subjects such as definitions, typologies, theories, databases, secondary sources, and literature, and includes a bibliography of terrorism.

Further, there are myriad of articles considering research on terrorism from all aspects, such as content, methodology, databases, and data-analysis techniques. Methodological discussions and state situations stand out as major issues in the field. For example, Silke notes that terrorism studies have gained only incremental improvements in methodology. More-recent critical terrorism studies discuss a new approach regarding the epistemological and ontological problems in terrorism studies. It is clearly recognized that terrorism has drawn the attention of scholars worldwide.

Reviews of context and methodological perspectives have contributed to the knowledge accumulation in the terrorism domain. These kinds of studies are necessary academic endeavours because they facilitate the determination of boundaries of the field, crystallization of the concepts discussed, and exploration of appropriate research methods. These reviews help reveal the challenges encountered in the academic field so that the discipline can further develop.

However, despite the the fact that terrorism has been a major aspect of Turkey’s political environment since the early 1960s, there is no comprehensive research examining Turkish terrorism studies in particular. This article aims to fill this gap by examining Turkish academic studies and views on the subject of terrorism with respect to their context and methodology. Therefore, the research was conducted through an exploratory perspective, seeking to find out the condition of Turkish terrorism studies compared to international work.

This article is divided into two main parts. In the first part, we examine contemporary international terrorism studies and new trends, discussing conceptual and disciplinary matters and then methodological achievements and challenges. In the second part, we assess terrorism studies in Turkey longitudinally perspective via context and methodology. We employed primary and secondary data sources, along with qualitative and quantitative analysis techniques, to reveal and evaluate the academic knowledge related to Turkish terrorism studies. We generated three different datasets for this purpose. First, we coded master’s theses and doctoral dissertations registered with the Turkish Higher Education Council (Yükseköğretim Kurulu, YÖK) Thesis Center since 1985., Turkish Hezbollah, Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (Devrimci Halk Komünist Partisi Cephesi (DHKP-C)), Liberation Army of the Workers and Peasants of Turkey (Türkiye İşçi ve Köylü Komünist Ordusu (TIKKO)), El Kaide, HAMAS, and Armenian Secret Army)) Second, we classified articles about terrorism published in academic journals according to their research purpose and methodology. Third, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 31 academics, and asked them to fill out a questionnaire comprising eight open-ended questions and four list- and scale-type questions, which we developed based on the literature review and a pilot study.We then analyzed all the information except for the interviews via descriptive statistics and content analysis, and analyzed the data generated by the interview questions through content and discourse analysis.

2. Contemporary Terrorism Studies: The Evolution of a Research Field

The evolution of studies on terrorism can be understood through five stages. The first stage is commonly accepted to be the appearance of a new academic research topic between 1960 and 1969. Although terrorism was perceived as a sub-form of political violence rather than a stand-alone research subject, scholars such as Crozier, Thornton, and Walter conducted some seminal research on terrorism in this period. This era can be recognized as preparation for emergence of the field as a bona fide discipline.

The second stage of terrorism studies, which took place from 1970 to 1978, is considered by some scholars as the launch or emergence of the field. It was the most productive era, with 40% of all publications until 1990 generated during this period. Additionally, researchers, academics and professionals with a military or intelligence background doubled in numbers in these years. According to Schmid, terrorism was by then conceptualized as a “sui-generis” subject rather than as a sub-category of political violence, armed conflict, guerilla warfare or insurgency. However, developments in the research field did not occur by coincidence but by rising terrorist attacks, perpetrated particularly in Europe from the end of the 1960s onwards. After 1978, studies on terrorism levelled out.

As Reid contends, this stabilization occurred between 1979 and 1985, with a linear growth in publications and increasing specialization among researchers. The decline of most radical left-wing groups in the West and the end of the Cold War engendered a relative decline in international terrorism studies. The fourth stage, from 1986 to 1990, is considered a crisis in terrorism literature, since publications and membership in academic communities also declined as well as reduction of funds. Indeed, as Silke notes, there were only 100 researchers around the world researching and writing continuously

on terrorism in this period.

After 9/11, due to the vigorous reaction of the United States, studies on terrorism and counter-terrorism have escalated; 150 books on terrorism were published in one 12-month period, and at least one book has been published every six months since. Another study notes that over half of academic articles published between 1971 and 2003 were in the years 2001 and 2002, and peer-reviewed articles increased about 300% in those two years.

Further, courses and modules on terrorism and terrorism studies programs have begun at virtually every major university at the graduate and postgraduate levels. A growing numbers of doctoral researchers have been undertaking their dissertations on terrorism-related topics. In addition, the number of centers, organizations, institutes, programs, networks, and projects that seek to expand the research community’s collective knowledge of terrorism and related subjects has risen. This era has been the most productive to date for terrorism studies.

As an indication of rising interest in the research field, many peer-reviewed academic journals have been publishing periodically on terrorism or related subjects since the second era. Among them, Terrorism (1977-1991) and Studies in Conflict and Terrorism (SCT; 1977-) commenced its publications at the end of the second era, Terrorism and Political Violence (TPV; 1989- ) in the fourth, and Critical Studies on Terrorism (CST; 2008- ) in the fifth. Other academic journals such as International Security, Journal of Conflict Resolution, Journal of Peace Research, Security Dialogue, and American Political Science Review publish a broad range of topics with the addition of terrorism-related subjects.

The field of study, drawing scholars and practitioners from varied areas, however, has been facing essential challenges. One such challenge is the interdisciplinary character of the field, while another is related to its conceptual fragmentation.

2.1. Terrorism as an interdisciplinary research field

Although the figures on terrorism research are encouraging, there is ongoing debate about whether it meets the requirements for a stand-alone academic discipline. For a field to be considered a discipline it must have its own researchers, department, curriculum, products, concepts, and theories. An academic research field that does not meet these criteria could be classified as inter-disciplinary or multi-disciplinary.

Defining the field of terrorism as multi-disciplinary has some flaws. Academics from other disciplines may not have commonalities with terrorism researchers, and the former reflect their own disciplines’ perspectives and contexts when explaining terrorism issues. Defining the field as inter-disciplinary may be a better approach; even though experts studying a terrorism topic would be from different academic disciplines, a certain amount of integration is possible over topics, concepts, and methodologies.

Some researchers argue that terrorism research has the characteristics of a stand-alone academic discipline. According to Jackson, the field is considered to have consistent shared assumptions, narratives, and labels about the definition, nature, effects, threat, causes of terrorism, and responses to it. Schmid supports this notion by arguing that, despite its shortcomings, terrorism studies has matured. He asserts that a fairly solid body of consolidated knowledge has emerged, and that many researchers in the field have great integrity.

However, according to a study that examined articles in TPV and SCT for the years 1990-1999, the backgrounds and specializations of authors are mostly aggregated in the discipline of political science (48.6%). There is also a considerable number of government officials (9.6%), military (3.3%), and law enforcement personnel (2%), adding up to almost 15% of authors. This makeup is not surprising because the terrorism field needs people in hybrid careers. Practitioners’ contributions should not be overlooked because, as Sageman claims, “we have a system of terrorism research in which intelligence analysts know everything but understand nothing, while academics understand everything but know nothing.” This comment reveals the importance of collaboration between academics and practitioners.

Another issue on the terrorism studies field arises from authors’ academic background and experience. Many do not have an adequate experience in the field, as there is no barrier to entry. There are more non-academic contributions in terrorism journals than in journals of political science or communication studies. For example, a study covering published articles in the 1990s notes that first-time authors wrote 83% of the articles. Similarly, Stampnitzky draws attention to the fact that “of 1,796 individuals presenting at conferences on terrorism between 1972 and 2001, 1,505 (84%) made only one appearance.” There is no continuity in Avcıterrorism studies, and researchers have not preferred it as a major research field. Further, experts have complained that the field is filled with self-proclaimed experts because there is little regulation about who can be accepted as a specialist.

Indeed, the problem of terrorism needs to be elaborated through different perspectives on levels of analysis such as individual, group, state, and international system. Each level has its own approach to understand the causes of terrorism and employ effective countermeasures. Therefore, terrorism studies have been affected by many academic disciplines, including political science, international relations, sociology, psychology, economy, history, and organizational and management studies.

It is very difficult to situate terrorism studies within only one academic discipline, and further examining terrorism and related issues in a single discipline may generate some interpretation problems. As Toros and Gunning point out, due to the problem of fetishization, terrorism cannot be understood apart from the context in which it emerged and developed. The field’s interdisciplinary character reflects its nature, which is realized by analyzing various disciplines’ concepts and theories. Hence, the phenomenon of terrorism needs to be studied thoroughly in order to reach an integrative approach that comprises all aspects of the considered disciplines.

2.2. The conceptual fragmentation of terrorism

Stampniztky argues that prominent authors in terrorism studies have not been able to define the field’s concepts nor delineate the boundaries. Crenshaw states that the lack of agreement on the definition of terrorism, difficulty in creating a comprehensive theory, and having too much event-based research are essential problems that the field faces. Confirming the definitional problem, Gurr draws attention to speculative interpretations and the problems in developing standard prescriptions for counter-terrorism.

Although many in academic and governmental circles have tried to define terrorism, there is no agreement and, indeed, a large chasm among the suggestions. Elements of the definition differ; governments and organizations focus on the criminal character of terrorism while academics focus on its political character. Indeed, in academic studies, the political element of terrorism is the most-featured characteristic after violence.

Moreover, there is a dearth of conceptual studies; only eight articles have been published between 1990 and 1999 and seven articles between 2000-2007. One of the underlying causes of this problem stems mainly from the contestation of ideologies and political objectives. There is no act of violence that is in and of itself deemed to be inherently terrorist, and terrorism is a method used by variety of actors. Moreover, the modern meaning of terrorism is pejorative, especially after “second wave” of terrorism. Further, despite the fact that almost all goverments and international organizations condemn terrorism, no organization calls itself ‘terrorist,’ and there may be little agreement between states whether a particular organization is ‘terrorist’ or not.

Since terrorism is a political subject and some governments and international organizations have differing (and competing) interests, there is also no universally recognized terrorist organization list. Therefore, it can be stated that although there is no agreement on the definition of terrorism, there is agreement that there is no commonly accepted definition of terrorism.

Because of this conceptual fragmentation, it has been noted that terrorism studies is a static environment, where the same ideas, definitions, hypotheses, and theories continue to be analyzed, assimilated, published, cited, and publicized by the media. Although there is considerable amount of publication in the field, Schmid complains that much of it is “impressionistic, superficial, and at the same time often also pretentious, venturing far-reaching generalizations on the basis of episodal evidence.”

It is contended that a lack of self-reflexivity and contextualization, ahistoricity, statist bias, and a dearth of fieldwork are among the essential problems of the field. Avishag Gordon calls terrorism research a “multi-paradigmatic research field,” and Reid and Chen confirm this finding by stating that the intellectual infrastructure of contemporary terrorism studies has been influenced by studies on conflict, foreign policy, regional issues, and political violence. The problems over the field’s definitional and disciplinary aspects somewhat reflect the methodology as well.

2.3. Methodological concerns on terrorism research

Studies on terrorism have been criticized for poor research methodology. Schmid and Jongman have noted that “there are probably few areas in the social science literature in which so much Avcıis written on the basis of so little research. Perhaps as much as 80% of the literature is not research-based in any rigorous sense.” Terrorism articles in peer-reviewed journals between 1971 and 2003 are considered mostly “thought pieces,” theoretical discussions, or opinions; only about 3% of them employ some kind of empirical analysis. Many researchers are often poorly aware of what has already been done in the field and are naïve in their methods and conclusions.

One of the causes of methodological weakness is to employ secondary sources widely, such as scholarly books and articles, media and news services, open government documents, and records originating from terrorists/sympathizers. Sageman concurs with these arguments by implying that terrorism research has stagnated because of the lack of primary sources and vigorous efforts to police the quality of research. Affirming this flaw, it is argued that no new data or knowledge has been produced because of the heavy reliance on open-source documents among terrorism researchers. It is pointed out that the 62% of studies were based on documentary analyses/reviews, while just 1% were structured and systematic interviews.

It is very difficult for researchers to have reliable and valid information without primary sources. However, reaching sources that meet academic standards is not easy because of the clandestine natures of terrorist organizations. These impediments, combined with time and funding limitations contribute to the difficulty of gathering empirical evidence.

As a secondary source, event datasets provide information on terrorist-related acts, and according to one study, there are more than 30 such datasets. This data is beneficial for researchers in learning who perpetrates terrorist acts, types of terrorism, targets of attacks, and changing trends over time. Datasets are also used to test hypotheses in a quantitative manner.

However, there are some difficulties in relying on datasets. Since there is no agreed definition on the concept of terrorism and a lack of reliable sources for gaining information to develop the datasets, researchers are reluctant to rely on the datum in terms of comprehensiveness and reliability. Coding errors, limited or no records of sources, lack of information, unreliable sources, and inherent uncertainty are recognized as problems with credibility and validity. Further, it is obvious that the governments are not eager to fund research projects or give out information on terrorist-related events because of the concern about researchers uncovering classified information. These roadblocks thus affect the quality of the product.

Another problem with terrorism research is the weak employment of statistical analyses comparing to other social science research fields. The statistical method, indeed, gives the researcher a useful tool to manage rough and big datasets successfully, and to explain and predict the variables in a causal manner. There is an expanding tendency to use statistical methods in articles appearing in the main terrorism journals, however, there are limitations to solely using statistics to understand social phenomena such as terrorism. One limitation is that statistics are usually applied in quantitative analyses more than qualitative. The debate on this classification emanates from the pursuit of achieving objective and scientific knowledge; the main objective of a qualitative study is to describe a situation, phenomenon, problem, or event. Although it is beyond of the article’s scope to discuss this issue in detail, it should be noted that there are ongoing debates about using the two methods in an “analytical eclectic model” for studying terrorism-related issues. Given that the main point of any research is to answer the stated research question(s), the most appropriate method and means to do so must be utilized. Thus, the means should not be a substitute for the ends.

There is a new research approach called critical terrorism studies, whose scholars believe that there are epistemological and ontological problems in terrorism studies in addition to the methodological concerns. They feel that the positivist methods used in the research do not reflect the facts of the field. These scholars argue that the most essential issue emerges from the conventional wisdom of Westerners, who try to understand non-Western problems with Western methodologies and points of view. Moreover, Jackson states that since any social researcher cannot analyze independently of his or her culture, values, perception, and identity, the categories or arguments deduced from the field can only be understood as the products and components of the researcher’s political-historical background, even though they may not intend to present them this way. In politics, key terms are often value laden, and appeal to emotions. As a socially constructed academic subject and as a type of political violence, terrorism studies would be even more open to these kinds of conjectures.

Further, the politics and interests of governments have likely affected terrorism studies. Silke points out that terrorism is an emotional subject, and it is relatively rare to find objectivity in the field; researchers’ work may reflect their feelings about terrorism, similar to any other social field. Jackson claims that terrorism studies also intrinsically carry political and ideological tendencies, and he adds that terrorism studies cannot be evaluated separately from government ideology. Indeed, Schmid indicates that political biases and mistaken assumptions can be found in terrorism studies more than in others. Thus, staying neutral in terrorism research is challenging, particularly when studying domestic terrorism.

As a large number of scholars study terrorism-related subjects, ranging from conceptual issues to theoretical assertions, the research field, gains an avalanche of concern from all perspectives. Prominent examples of this field's wide range of topics are definitional and conceptual attempts, historical perspectives, the exploitation of religion and ethnicity as motivators, terrorist acts as a way of communication, organizational perspectives, the dynamics of insurgencies and rebellion, social movement theory, democratization and terrorism, psychological approaches to terrorist behavior, counterterrorism methods, and intelligence on terrorism. However, one of the important problems of contemporary terrorism studies arises from the lack of coordination and regulation of academic efforts and field experience. Notwithstanding the foregoing difficulties faced by terrorism studies, as Schmid argues, there is a fairly solid body of consolidated knowledge, datasets, and well-known scholars in international terrorism studies. In this regard, the contemporary terrorism field presents a perspective, which is open to improvement.

After scrutinizing the literature on the evolution of terrorism studies and the methodology employed, it is found that there are three main shortfalls in international terrorism studies. First, the area has not developed its own concepts and theories, and this conceptual fragmentation sparks the discussion on whether terrorism studies is a stand-alone field. The other problem stems from the character of the terrorism field; terrorism studies are intrinsically value laden. Since terrorism is a type of political violence, researchers and officials are not able to detach themselves completely from terrorist events. The last problem consists of methodological concerns: any social research area has challenges with methodological perfection, but terrorism studies seem to experience more than other fields.

3. Terrorism Studies in Turkey

This section of the paper explores the situation of Turkish terrorism studies by using the frame drawn by the literature on international terrorism studies, which, to recap, includes the issues of whether the field is its own discipline and its methodological inadequacies.

3.1. Volume of terrorism studies in Turkey

Some essential characteristics of an academic discipline can be identified as having accumulated knowledge, departments, and research institutes working in the field. The early sign of this development in Turkey comes out with the beginning of postgraduate programs on terrorism by state- affiliated institutions and colleges after the 2000s. The first postgraduate program on terrorism began in 2002 at the Turkish Military Academy Defense Sciences Institute (Kara Harp Okulu Savunma Bilimleri Enstitüsü, KHO SAVBEN) at the master’s degree level under the International Security and Terrorism program, and doctoral education there began in 2006. Another institution, the Police Academy Security Sciences Institute (Polis Akademisi Güvenlik Bilimleri Enstitüsü), started its postgraduate programs in 2001 and currently has two postgraduate programs: International Security and Security Strategies and Management. Although there is no other postgraduate program focusing on terrorism, the Turkish War Colleges Strategic Research Institute (Harp Akademileri Stratejik Araştırmalar Enstitüsü, HARPAK SAREN), Sabancı University, TOBB University of Economics and Technology (Türkiye Odalar ve Borsalar Birliği Ekonomi ve Teknoloji Üniversitesi, TOBB ETU), Istanbul Aydın University, and Istanbul Gelisim University have postgraduate programs on security, conflict resolution, and strategy-related topics.

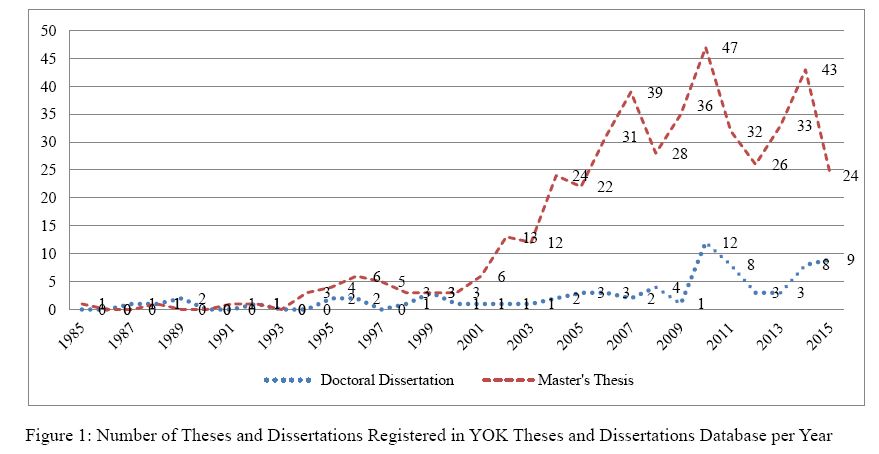

Thanks to the research institutes and programs, masters’ theses, doctoral dissertations, and articles on terrorism have burgeoned in Turkey since the 2000s. To date, there are 521 theses and dissertations on terrorism, 446 of which are at the master’s level and 75 of which are at the doctoral level. The types and years of the dissertations and theses are shown in Figure 1.

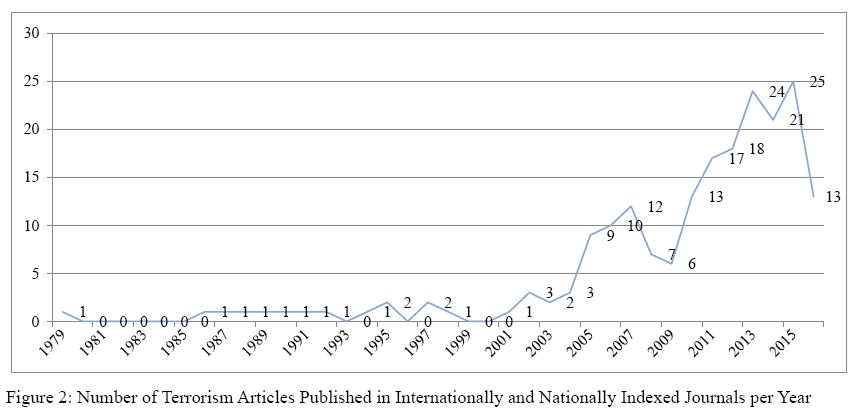

The first dissertation was registered to the National Thesis Center in 1987. Only 52 theses and dissertations on terrorism (15 doctoral and 37 master’s) were registered between 1987 and 2001, and 90% of total theses (60 doctoral and 409 master’s) were recorded after 9/11 attacks. Between the years of 2010 and 2014, during which studies reached their peak numbers, a total of 90 master’s theses and 20 doctoral dissertations were written. We found similar numbers for articles on terrorism. According to data extracted from internationally indexed journals and the journals indexed by TR Dizin Social and Humanities Sciences Database (SHSD), a total of 198 academic articles (112 TR Dizin, 86 internationally indexed journals, Web of Science [WoS]) complying with the aims of this study were found, as shown in the Figure 2.

It is remarkable that between 1979 and 2003 only 20 articles were published in Turkey on terrorism. These numbers began to change in 2004, as depicted in Figure 2, and reached their highest levels in 2013 and 2015. As the compiled dataset shows, 93% of the articles were published after the 9/11 attacks, which shows the similar trend like the theses and dissertation dataset.

The authors of dissertations and articles share one other essential point. It is found that almost 16% of articles and 24% of doctoral dissertations were written by authors who work(ed) for security agencies and state institutions. This finding is supported by an interviewee’s statement that “most of the authors are soldiers and law-enforcement officers.” This comment implies that state-affiliated academic institutions generate a considerable account of studies, and terrorism-related topics draw the attention of many practitioners in Turkey.

Additionally, there are nearly 30 research centers and think tanks in Ankara and Istanbul studying security, international relations, and global and regional issues. Most of these institutions were established after the 2000s. Even though all of these centers focus on regional and international security and related issues, and many of them have been publishing monographs and reports on terrorism-related issues since their foundation, only one contains “terrorism” in its title.

3.2. The question of terrorism as a stand-alone academic field

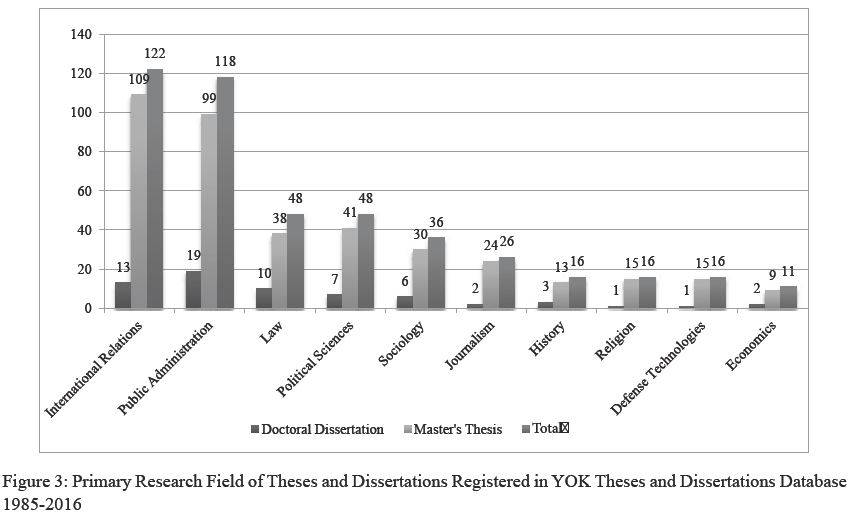

Although the academic publications in Turkey on terrorism are relatively numerous, and terrorism studies are now part of undergraduate, graduate, and postgraduate programs at universities and institutions, the academic state of terrorism studies in Turkey is still under debate. In the interviews we conducted, 90% of participants responded that “terrorism is a study area or subject, not an academic discipline or sub-discipline.” Scholars who study this area stated that Turkish terrorism studies is not a stand-alone field, but related to many academic disciplines. This claim is supported by the dataset generated for theses and dissertations (Figure 3).

The theses and dissertations we examined at the registry are related to 37 different academic branches, according to the Turkish Higher Education Council. In this context, 76% of all theses/dissertations the scientific branches of International Relations, Public Administration, Political Sciences, Law, Sociology, and Journalism. Almost half (46%) relate to International Relations and Public Administration.

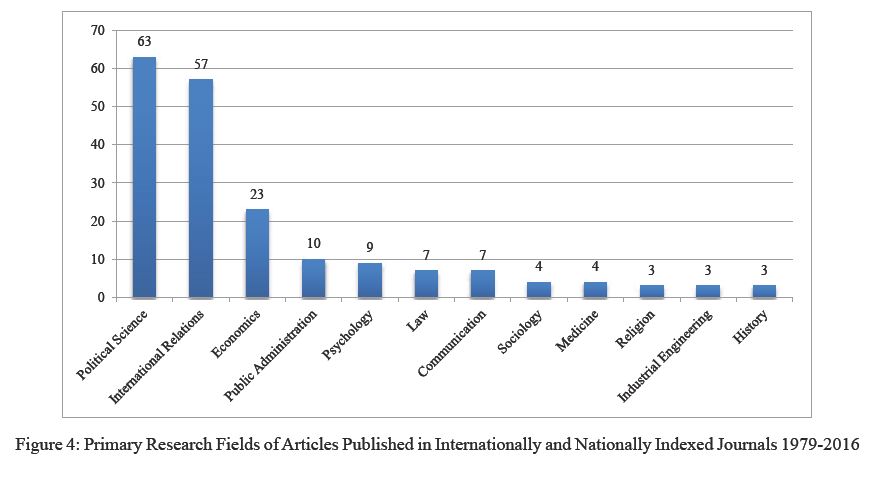

The 198 articles distribute among 15 disciplines, 12 of which are as shown in Figure 4. Political Sciences leads the classification, with 63 articles, and International Relations follows, with 57 articles. As shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, Turkish terrorism studies is part of many disciplines, but International Relations, Political Science, Economics, and Public Administration are the top four.

It is also found that the varying topics and disciplines reflected in terrorism research are related to the supervisors of dissertations. After examining the names of the doctoral advisers, we found that one professor supervised 10 dissertations in total, while four professors advised two dissertations each, and 57 lecturers advised only one doctoral dissertation per person. We also note that most of the lecturers supervising doctoral dissertations are (were) PhDs or associate professors in International Relations. The problem of the one-time researcher emerges in the articles dataset as well. In the 198 articles, there are 268 authors (some articles are multi-authored), and only 25 of these authors have written more than one paper. Therefore, it can be argued that not many academics in Turkey are studying and writing regularly on terrorism.

The abovementioned findings and discussions indicate that Turkish terrorism studies draws the attention of academics and staff from varying disciplines, state-affiliated institutions, and government officials. The authors then asked participants the following question: “According to you, of which academic discipline is terrorism a sub-study area or sub-discipline and in which order would you list them?” The findings are shown in Figure 5.

The graph shows that the terrorism field is seen as linked with many disciplines, but most participants feel it is a research topic under International Relations, Political Science, and Sociology, respectively. These findings are also compatible with the dissertation and articles datasets, except for Public Administration and Economics. A probable reason for these results is that the most participants have academic degrees in International Relations. Another one is that the rigorous methodology of an academic discipline, such as Economics, allowed researchers more opportunity to publish their pieces in peer-reviewed journals despite their lack of knowledge on the context of the particular field. Another possibility is that since the majority of the authors of the theses/dissertations are (were) working in government offices, perhaps they opted to register their document under the Public Administration discipline.

One of the findings reached after analyzing the primary and secondary sources is that terrorism is generally viewed as a sub-field of many scientific disciplines. Our findings suggest that Turkish terrorism studies has a multi-disciplinary character; strong evidence of this result can be found in the answers of our survey respondents. For instance, most participants answered the question of “What is the main problem in terrorism studies?” with “insufficient knowledge of the area.” The participants accept that terrorism is a (sub)research field, but also state that researchers from many academic disciplines write on terrorism with little knowledge of the basic concepts and theories. Moreover, in Turkey, it should be noted that “terrorism studies” or “terrorism” is not recognized as a field of specialization under any academic discipline in the classifications determined by the Council of Universities (Üniversitelerarası Kurul). This situation is a drawback for researchers who intend to have a career in terrorism studies in particular, because the Council of Universities is the main body establishing the criteria for academic promotions.

3.3. The value-ladenness of Turkish terrorism studies

The findings thus far raise some important questions about Turkish terrorism studies. One of them is why the field only expanded after 2001, as the international field did, in spite of the fact that Turkey has been a target for terrorist organizations since the 1960s. Another question arises about the reasons over the fluctuating numbers of theses/dissertations and articles in Figure 1 and Figure 2; 2007, 2010, 2013, 2014 and 2015 have the highest numbers of theses, dissertations, and articles.

One possible explanation for both questions that students with masters or doctoral degrees in the subject graduated from scientific institutions founded since 2000s, and that there has also been an escalation in the numbers of freelance research centers and think tanks in those years. It could also be argued that some scholars and researchers have shifted their academic concerns from other disciplines to terrorism because it became a popular topic after 9/11.

The question of fluctuation was elaborated in the interviews, for example: “Academics abstain from writing about problematic issues because of fear of terrorist organizations or emotional causes; they prefer to write on terrorism-related issues when violent attacks decline and the security situation remains relatively stable.” Another participant said that “terrorism is a current problem, and while terrorist organizations are committing their attacks it is very difficult for researchers and editorial boards of the journals…to decide that publishing about terrorism” should be considered.

To determine whether these comments had merit, we compared terrorism attacks in Turkey and the dates of academic publications on the subject. As evident from Figure 6, the most devastating years for terrorist attacks in Turkey were 1977, 1990-1994, 2012, and 2015. Publications on terrorism by Turkish authors rose through 2007, and were at their lowest levels in 2012 and before the 2000s. Although it seems that there is no relation between terrorist attacks and academic publications, to be sure, we conducted a correlation analysis and could not find a significant correlation (r=0.01; p>0,9) between terrorist attacks and Turkish terrorism studies. We repeated the analysis with the lagged values (one and two years) of publications, but it either shows no significant correlation. Therefore, there is no convincing evidence on the relation between terrorist attacks and academic publications.

We also examined the effect of emotional factors on the publications. This possibility was suggested to the participants with the following questions: “Do you think that terrorism studies are affected by the socio-cultural position or thinking style in which the researchers are living? If you compare this issue to the other academic disciplines, is it possible to say terrorism studies are affected by the researchers’ social roles more than any other area of social sciences?” 40% of participants commented that “being impartial in terrorism studies” is very important, but is difficult to do compared with other fields. According to the participants, emotional factors have considerable effect on the neutrality of researchers. Indeed, one of our findings supports this idea: out of 75 dissertations, 31 theses are not accessible in the National Thesis Database because the authors have not given permission for access.

Another indication of the emotions play in research can be found in the publications themselves. In order to grasp the real picture, we examined titles, abstracts and keywords of the dissertations and articles and regrouped them thematically. Figure 7 shows that doctoral dissertations, mostly focus on terrorism and law, counter-terrorism, terrorism in Turkey, international terrorism, terrorism and media, religion-based terrorism, financing of terrorism, and human rights.

Moreover, most articles focus on counter-terrorism and international terrorism. Terrorism in Turkey and causes of terrorism come second and third (Figure 7). The thematic codification of the titles and abstracts of dissertations and articles indicate that Turkish terrorism research varies widely by topic. However, terrorism in Turkey itself has not been an attractive research field; we found that 52% of the theses/dissertations and 87% of the articles do not cover topics related directly to Turkey.

It can be inferred from the above findings that terrorism is not an academic topic that is preferred and studied easily in Turkey. Emotional factors and the value-laden aspect of the subject plays into this finding, but there are also serious methodological issues.

3.4. Methodology in Turkish terrorism studies

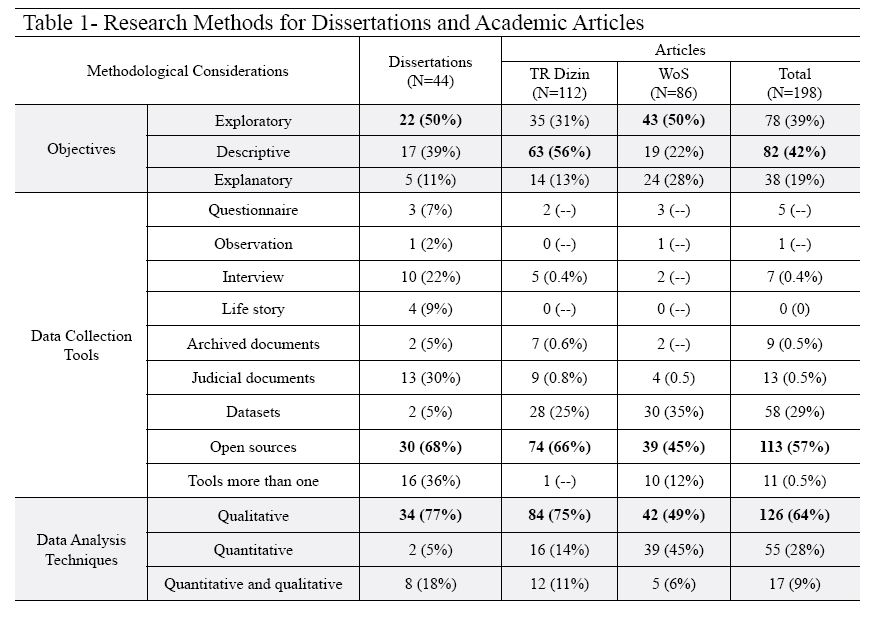

Research can be conducted via varying methodological perspectives. For example, Kumar classifies perspectives into three types: applications of the research study, objectives of the study, and type of information sought in the study. In another study, research approaches are categorized as follows: basic philosophy, objective, methodology, period of study, and unit of analysis. For the purposes of this study, we categorized the theses/dissertations and articles into objectives, data collection tools, and data analysis techniques. In this context, the study objectives consist of descriptive, explanatory, and exploratory questions; the tools for data collection were the questionnaire, observations, interviews, life stories, judicial documents, archived records/documents, datasets, and open sources; and last, the quantitative and qualitative techniques were part of the data analysis. The methodological characteristics of the dissertations and articles are shown in Table 1 below.

Regarding research objectives, doctoral candidates preferred exploratory researches, while the article authors chose to publish in descriptive and exploratory manners. Since exploratory studies generate new ideas or conjectures –which is expected from PhD candidates– this finding is not surprising. Descriptive studies share a big portion (42%) of articles, and second (39%) in dissertations.

Exploratory and descriptive studies aim to fill the gap in any field by setting the scene and by identifying the main forces at work that are not well known or researched. These two research purposes encourage scholars to study cases and analyze them qualitatively. Indeed, we found that 45% of the articles and 32% of the dissertations were carried out by the case study method.

Suprisingly, there are fewer dissertations (11%) and articles (19%) that attempt to explain a situation or a problem by examining the relations between the variables from an explanatory perspective. Comparing the articles in TR Dizin to the articles in internationally indexed journals (WoS), we see that explanatory and exploratory approaches dominate international articles, at 78%. This finding may be the consequence of the standard put forward by the internationally academic journals.

Explanatory study is the highest academic level of understanding a subject. Its particular aim is to explain what happened, what is happening, and what will happen. In this study, we found that explanatory studies were infrequently practiced comparing to other types. An important reason for this result is that there is not sufficient accumulated knowledge in the terrorism field. The other reason, to be explained below, is that there is a lack of reliable and valid data; explanatory research mostly requires hypothesis testing, and that requires quantitative data collected from the field.

In other findings, only 14 of the doctoral dissertations depended upon primary data collection tools and 30 dissertations benefitted mostly from secondary sources. The authors of articles also collected data mostly from secondary sources, with primary sources used only in 13 articles. In addition, most of the studies were performed with a literature review of open sources, such as published articles, books, and web searches. These findings are significant because they signify that Turkish terrorism studies are almost solely based on secondary sources and literature reviews, which Silke calls “integrators of literature.”

Indeed, this finding was reiterated in the interviews; participants agreed that “academic studies have methodological weaknesses.” Additionally, to the question of “What are the methodological problems in terrorism studies in Turkey?” most participants responded with “not having analyses based on data” and “difficulties of data collection.” Although there are multiple international databases on terrorism-related events, which are preferred by the authors of articles in internationally indexed journals, these databases have limitations. They suffer from different definitions of terrorism, missing values on dates and events, and being hinged on open sources. For this reason, there is no reliable database based on official documents that compile and classify terrorist attacks committed in Turkey. Further, the security institutions holding this kind of information have not been sharing it with the public for secrecy reasons.

The problems with collecting useful data reverberate through the analysis techniques. A lack of coherent datasets inhibits the quality and practicability of quantitative analysis. Thus, qualitative analysis techniques were used in 34 dissertations (77%) and 126 articles (64%), while quantitative analysis was used just in two dissertations (5%) and 55 articles (28%), the latter mostly in the articles from internationally indexed journals. Further, some studies (18% of dissertations and 9% of articles) employed quantitative and qualitative analysis concurrently.

It is also noteworthy that quantitative analysis was mostly used by researchers with an academic background in Economics. When we look at these techniques in detail, descriptive statistics (16% of dissertations and 11% of articles) and inferential statistics (9% of dissertations and 22% of articles) in quantitative analyses, as well as content and discourse analyses in qualitative techniques, were prominent. This fact is congruent with the findings derived from the research objectives and data collection tools, which all point to the lack of analytical studies.

In addition to these weaknesses, there are also some basic methodical problems in the articles and dissertations. For instance, 50% of the articles did not state the aim of the study. Further, there are no keywords in about 14% of articles in TR Dizin and in 44 doctoral dissertations out of 75 examined. This finding was unanticipated because such Avcıstatements are common and mandatory procedure for academic publications. These problems indicate that writing techniques and screening procedures for journals in TR Dizin need to be improved.

4. Conclusion

Although international terrorism studies is showing signs of becoming a stand-alone discipline, our examination of Turkish terrorism studies revealed that there are several impediments for this field specifically. The first is that it has a multi-disciplinary character, bearing largely other disciplines’ approaches, concepts, and theories. The field does not have its own researchers, authors, or supervisors of dissertations and interviews, and most articles were written by one-time authors. Due to these factors, Turkish terrorism studies tend to lack the distinct terminology and theoretical accumulation created by scholars of international terrorism studies. These problems seem to be related to the field’s multidisciplinary aspect, such that it does not have an interdisciplinary perspective or is a stand-alone discipline.

Terrorism research is intrinsically value laden. Although there is not much evidence, we suspect from the comments of our interviewees, that authors of terrorism studies have been affected by their own emotions, values, and identities. For this reason, they likely hesitate to touch upon ‘sensitive issues.’ However, this issue is not specific to Turkish terrorism studies; it is argued that international terrorism studies also reflects this vulnerability.

Regarding methodology, a significant problem of the terrorism research field is that the studies are mostly composed of literature reviews or are based on secondary sources. The barriers to reaching primary sources result in the unsatisfying analysis of research problems. Moreover, there is no compiled comprehensive terrorism dataset for terrorist attacks committed in Turkey. These last two issues likely impede the quantity of research focusing on terrorism in Turkey, and, in contrast to the aim of science, which is to produce new knowledge, the area’s methodological weaknesses contribute to the reproduction of already-known facts.

These problems should be appraised as opportunities to develop the field. For example, practitioners could aim to produce collaborative papers with academics from different disciplines. Another opportunity is to develop a dataset comprising terrorist attacks in Turkey by synchronizing official documents and open sources to facilitate reliable data-based analysis. Further, an academic journal with rigorous screening and editorial policy could consolidate studies on terrorism.

Nevertheless, problems such as the field’s multidisciplinary character, transient authors, a lack of reliable and valid datasets, the dearth of primary sources and quantitative analyses are among the significant problems mentioned by many international studies on terrorism. The international field has been striving to solve these problems, for instance, by founding comprehensive datasets and by the growing numbers of analytical studies. When considered from this point of view, it can be argued that Turkish terrorism studies has been experiencing difficulties faced by the international field almost 20 years ago. Silke’s comment on international terrorism studies between 1995 and 2000 could apply Turkish terrorism studies now: “it exits on a diet of fast-food research: quick, cheap, ready-to-hand, and nutritionally dubious.” We feel that our study, as a preliminary assessment, can satisfy a need in the academic field and can contribute to improving perspectives on strategies for countering terrorism on the ground, which is one of the most important contemporary security threats in Turkey.

*This article is an extended and updated version of our paper, presented at VII. Conference on International Relations Studies and Education, held by the Council of International Relations and Yasar University on 28th April, 2016.