Şener Aktürk

Koç University

In this article, I critically evaluate the causal and temporal dimension of social scientific studies focusing on Turkish politics. A very important and yet often neglected aspect of social scientific analysis involves the temporal dimension of causal processes. The temporal dimension of causal processes has direct consequences for operationalization and measurement, and hence it is an essential component of research design. Does the dependent variable (outcome) of interest unfold over the short term or the long term? Do the hypothesized independent variables (causes) unfold over the short term or the long term? Paul Pierson (2004) provided a classification of four types of causality based on the temporal dimension of causes and outcomes using metaphors of natural disasters: tornado, earthquake, meteorite, and global warming. Operationalization and measurement of long term causes and outcomes pose a major challenge, compounded by the challenges of periodization of causes and effects. Unfortunately, a large proportion of the studies of Turkish politics do not have a clearly discernible independent variable (cause) to begin with, and they are thus better characterized as works of “non-causal description.” Moreover, many of the studies of Turkish politics tend to imply, but rarely state explicitly, a global warming type of causality (long term cause and long term outcome), which necessitates focusing even more intensively on such challenges of measurement and periodization. Yet the operationalization of the key (dependent and independent) variables is often missing even in articles published in reputable academic journals of Turkish politics and society. In the spirit of constructive criticism, I suggest a number of guidelines for research design in order to address the problems of causality and temporality discussed in this article, including awareness of multi-temporal equifinality.

1.Temporal and Spatial Context of Causality: Identifying the “Epicenter” and the “Moment”

Causal processes occur in specific contexts that envelop and limit them in definite directions. Most importantly, each causal process occurs in a time-specific and space-specific context, which channels, shapes, and limits its various manifestations, consequences and influences. As such, the temporal and spatial peculiarities of specific causal relationships receive increasing attention in tandem with methodological advances in the social sciences.[1] The centrality of time and space for understanding the unfolding of causal processes is at once somewhat obvious and yet systematically neglected. One of the goals of this article is to raise awareness about the variable “concentration” of causal relationships in specific time(s) and space(s). As such, it would be very useful if scholars acknowledged and identified the specific temporal and spatial features of the causal relationship that they seek to explain in their research and publications. Simply put, there is no causal relationship, and no cause or effect, that is omnipresent across all time and in all spaces.

In terms of their spatial-temporal context, almost all causal processes are akin to earthquakes, which occur in a very specific moment (usually seconds) and at a geographically specific “epicenter,” measured in terms of their magnitude, which then diffuse in geographical and temporal waves to cover a specific territory, which is never the entire earth but rather a small territory within earth. The earthquake metaphor, which will be used in a different and more restrictive capacity later in this article, is also revealing in terms of the intimate connection or interdependence between the spatial and the temporal aspects of a causal process or influence. It is nonetheless curious that despite the increasing usage of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and geospatial technologies in general in order to capture the spatial dimension of causal processes, no temporal corollary to the GIS has been developed in a popularly useable and transferable format in order to capture the temporal dimension of causal processes. In this article, bracketing the spatial dimension of causality, however significant it may be, I will focus on the temporal dimension of causality, while reflecting on its various ramifications in the case of Turkish studies.

2. Temporal Dimension of Causality: Tornado, Earthquake, Meteorite or Global Warming

In an influential book chapter,[2] followed by an even more influential book,[3] Paul Pierson classified causal arguments into four different categories based on the temporal dimension of the main cause (independent variable) and the main outcome (dependent variable) in the hypothesized causal relationship. He labeled these four types of causal relationships with reference to natural disasters: Tornado (short term cause and short term outcome), meteorite (short term cause and long term outcome), earthquake (long term cause and short term outcome), and global warming (long term cause and long term outcome). Based on his conceptualization of these four different types of causality, Pierson launched a convincing critique of American political science for being excessively concentrated on a “tornado” (short term cause and short term outcome) type of causality, as evidenced by the articles published in the American Political Science Review, American Journal of Political Science, Comparative Politics, and World Politics, the four leading American political science journals.[4] The excessive focus of American political science on a tornado type of causality was, and still is, the result of a disproportionate reliance on quantitative research methods, especially inferential statistics, which establish or hypothesize (or construct) causal relationships through correlations between narrowly time specific (e.g., GDP per capita in the year 2000) causes and narrowly time specific outcomes (e.g., weekly church attendance in the year 2000). As a result, Pierson recommended moving from a “snapshot” (variable-oriented, very short term) analysis that is hegemomic in American political science to “moving picture” (causal process oriented, long term) analysis, and drew attention to the fact that the founders of modern social sciences all adopted long term, process oriented explanations:

Contemporary social scientists typically take a ‘snapshot’ view of political life, but there is often a strong case to be made for shifting from snapshot to moving pictures. This means systematically situating particular moments (including the present) in a temporal sequence of events and processes stretching over extended periods… I seek to demonstrate the very high price that social science often pays when it ignores the profound temporal dimensions of real social processes… It is no accident that so many of the giant figures in the formative period of the social sciences—from Marx, Tocqueville, and Weber to Polanyi and Schumpeter—adopted deeply historical approaches to social explanation.[5]

As Pierson argued, a disproportionate reliance on the tornado type of causality as observed in the case of American political science, probably driven by quantitative methods, is likely to be problematic in trying to understand many of the causal processes in political and social life, in which either the cause(s) and/or the outcome(s) unfold over many years, decades, generations, or even centuries. Thus, Pierson’s critical review of the temporal topography of causal claims in American political science was a necessary and useful corrective to the mainstream scholarship. Reviewing and classifying all the articles published in the four leading American political science journals over five years (1996-2000), Pierson demonstrated that 51.8% of the articles published in the American Political Science Review, 56.6% of the articles published in the American Journal of Political Science, 49% of the articles published in Comparative Politics, and 24.4% of the articles published in World Politics were based on a tornado type of causality (short term cause-short term outcome).[6] In other words, with the notable exception of World Politics, which was identified as the leading journal publishing the largest proportion of articles analyzing long term causal relationships, the other three leading American political science journals disproportionately published research with arguments based on a tornado type of causality. Undoubtedly, as Pierson himself emphasizes, some of the significant social processes are based on short term causes leading to short term outcomes, and yet an excessive reliance on tornado type of causality could obscure the reasons behind some other outcomes of political and social significance, which have long term causes or long term outcomes.[7] However, I am also of the opinion that Tornado type of political outcomes constitute, at most a significant minority, but certainly not an outright majority of the most consequential and significant political outcomes of interest for social scientists. In a way, what I attempt to achieve in this brief article is to conduct a critical review of Turkish studies scholarship by focusing on the temporal dimension of causality, akin to what Paul Pierson has done in the case of American political science.

3. The Study of Turkish Politics: Between Non-Causal Description and Global Warming

In this article, I argue that the study of Turkish politics is characterized by the pervasiveness of non-causal description (i.e., studies without an independent variable) on the one hand, and an excessive focus on a Global Warming type of causality based on long term causes leading to long term outcomes on the other. In many ways, these weaknesses are not only different from, but even the apparent opposite of, what Pierson argued to be the problems of American political science. However, as I seek to demonstrate throughout this article, the pervasiveness of non-causal description and Global Warming type of causality in Turkish studies are indicative of far greater and more basic methodological problems than the problems implied by the pervasiveness of a tornado type of causality in American political science.

Secondly, even the seemingly long-term causes found in much of Turkish studies scholarship do not amount to the long-term “processes” that Pierson discusses. Rather, much of what can be classified as “long term” independent variables are either the result of very poor operationalization without any temporal specifications as to their beginning or end points (unclear starting point, and unclear end point, or no end point at all), and thus can be classified as being “long-term by default,” or they are structural variables that are, once again, long term by default because structural factors do not vary much in the short term. Therefore, strictly speaking, there are not very many studies employing a Global Warming type of causality as understood by Pierson either. Positing a long term process as an independent variable and as a dependent variable still necessitates an operationalization of its scope, temporal and otherwise (spatial, etc.), which is often lacking in the studies of Turkish politics.

4. Reviewing Turkish Studies and Uluslararası İlişkiler: Leading SSCI journals focusing on Turkey published in English and Turkish

There are many scholarly journals specifically focused on the study of Turkish politics, with different orientations, quality, and impact in the field. Among the journals solely or primarily focused on Turkish studies, which are also included in the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI), Turkish Studies is arguably the journal with the highest impact factor, and thus, the natural locus for a review of the current scholarship in this field.[8] The last six full years (2011-2016) of Turkish Studies includes a total of 217 articles published in 24 issues. Thus, on average nine articles were published in each issue, and 36 articles were published per year. This is a sufficiently large pool for gauging the distribution of the four types of causality that we are interested in. These articles were coded according to the temporal dimension of their main independent and dependent variables. In order to achieve a certain level of objective coding, not the author but a highly qualified research assistant who has taken the relevant methodology course, and who is well versed in Pierson’s typology, did the first round of coding for Turkish Studies. The current author reviewed and validated, and in very rare cases changed, the coding of the research assistant. Going through the abstracts of the articles first, and skimming the article if absolutely necessary, the independent variable and the dependent variable of each of these 217 articles were dichotomously coded as “short term” and “long term.” Such a coding normally generates four types of temporal causality that Pierson identified, which he labeled as Tornado, Meteorite, Earthquake, and Global Warming. However, even a cursory review of articles in the Turkish Studies reveals that there is a very large fifth category in the study of Turkish politics and society: articles without a clearly identifiable independent variable. These articles do not have a causal claim, and thus may be classified as articles based on, or providing, a “non-causal description.” (Table 1) In fact, there are 63 articles that can be categorized as “non-causal description,” while another 63 articles can be categorized as having a Global Warming type of causality with a seemingly long-term cause and a long-term outcome. These two categories together make up a large majority, 58 percent, of all articles published in Turkish Studies. Meteorites are a distant third, followed by Earthquakes, whereas Tornados are the least common, although they still make up 11.5 percent, corresponding to 25 articles.

Table 1- Articles in Turkish Studies according to the temporal dimension of their causality, 2011-2016

| Outcome (DV) | Cause (IV) | Causal Temporal Type | N=217 | Percentage of all articles |

| Short term | Short term | Tornado | 25 | 11.5 |

| Short term | Long term | Earthquake | 31 | 14.3 |

| Long term | Short term | Meteorite | 35 | 16.1 |

| Long term | Long term | Global Warming | 63 | 29 |

| Long or Short | None | Non-Causal Description | 63 | 29 |

How representative is this distribution of Turkish studies scholarship in general? Could this very peculiar distribution of temporal dimensions of causal claims be biased due to the journal of choice? In an attempt to achieve a somewhat more representative sample among top journals in the field of Turkish studies, and to gain additional leverage for the analyses that follow, I decided to expand and diversify the pool of articles by coding another leading journal in the area of Turkish studies, this time published in Turkey and mostly in Turkish, and yet still included in reputable international academic indices. There are only three Turkish language journals included in the Social Science Citation Index that can be considered as covering political science and international relations, and these are, in alphabetical order, Amme İdaresi Dergisi, Bilig, and Uluslararası İlişkiler. Although the impact factor of all three is very similar, and unfortunately very low by the standards of SSCI, Uluslararası İlişkiler and Bilig have comparable impact factors (0.080 and 0.098 respectively) that are clearly higher than that of Amme İdaresi Dergisi (0).[9] More importantly, Uluslararası İlişkiler clearly focuses on international relations, which, given the prevalence of positivistic schools of thought in the field of international relations, might privilege, and hence “oversample,” more causal analyses. In other words, if anything, Uluslararası İlişkiler should have more causal analyses compared to most other social scientific journals published in Turkey.

Table 2 summarizes the codings of 149 articles published in Uluslararası İlişkiler between 2011 and 2016 (inclusive). Once again, not the current author but another graduate student (different from the coder of Turkish Studies) coded the articles first, in part not to bias the coding in the direction of my expectations and the available findings based on Turkish Studies. The findings are truly striking: 84 percent of all articles published in Uluslararası İlişkiler over six years either have a Global Warming type of causality or no causal argument, which together constitutes a hegemonic majority far greater than the corresponding proportion (58 percent) found in Turkish Studies for the same two categories. Equally significantly, there were no articles with a Tornado type of causality, and only four articles (corresponding to a mere 2.7 percent) with an Earthquake type of causality. Compared to the absence or near absence of Tornados and Earthquakes, there were a remarkable number of Meteorite type of articles, 20 in total, corresponding to 13.4 percent of all articles published in Uluslararası İlişkiler.

Table 2- Articles in Uluslararası İlişkiler according to the temporal dimension of their causality, 2011-2016

| Outcome (DV) | Cause (IV) | Causal Temporal Type | N=149 | Percentage of all articles |

| Short term | Short term | Tornado | 0 | 0 |

| Short term | Long term | Earthquake | 4 | 2.7 |

| Long term | Short term | Meteorite | 20 | 13.4 |

| Long term | Long term | Global Warming | 81 | 54.4 |

| Long or Short | None | Non-Causal Description | 44 | 29.5 |

Despite significant and in part disciplinary differences, there are also two meaningful similarities between the composition of articles published in Turkish Studies and Uluslararası İlişkiler, which together reveal the “hierarchy” of temporal-causal claims in both of these journals: First, as already noted, articles that either have no independent variable (non-causal description), or independent and dependent variables that are both open ended or long term, constitute a very large majority of all articles published in both journals. Unfortunately, this is at least in part indicative of deeper problems in operationalization and measurement, even though there are articles that are exceptional in this regard. On the other hand, there are also a large number of “literature review” type of articles published in Uluslararası İlişkiler, which almost always (and understandably) lack a causal argument, and thus are at least in part responsible for the very large number of articles with a non-causal description in this journal of international relations. Second, among the three types of articles that have at least one “short term” variable, namely Meteorites, Earthquakes, and Tornados, there is a clear hierarchy: Meteorites are more common than Earthquakes, which in turn are more common than Tornados. This is also, at least in part, bad news from a methodological and operational point of view, because it indicates that article types with short term, strictly temporally delimited precise dependent variables (moment, event, legislation, etc.), namely Earthquakes and Tornados, are relatively rare in both journals, even when compared to Meteorites. We can now turn to a somewhat more detailed look at each category of articles.

5. The Pervasiveness of Non-Causal Description

An astounding 29 percent of all articles published in Turkish Studies, corresponding to 63 articles, do not have a clearly identifiable independent variable and/or they do not have a causal claim at all (Table 1). In a curious coincidence, almost exactly the same proportion, 29.5 percent of all articles published in Uluslararası İlişkiler do not have a clearly identifiable independent variable and/or do not make a causal claim. In other words, almost three out of ten articles published in Turkish Studies and Uluslararası İlişkiler either do not have, or do not attempt to make, a causal claim. This is in part understandable if one considers the multidisciplinary nature of Turkish Studies, since many scholars in the humanities and history often deliberately eschew causal claims. For example, a review of the Korean War in the Turkish press[10] or the reception of mainstream Turkish movies among the Belgian Turkish diaspora[11] are understandably in this category. However, there are also many articles in the fields of international relations and domestic politics without a clearly identifiable main cause or independent variable, which is not explicable in terms of disciplinary attitudes toward causality, since almost all subfields of political science, including international relations, comparative politics, and domestic politics, are shaped by theories with causal claims.

The prevalence of non-causal descriptive articles in Uluslararası İlişkiler-International Relations is somewhat more surprising since it is a journal of international relations, a field in which major schools of thought such as (Neo-)Realism and Liberalism, including their variations, are mostly committed to causal analysis. A closer look reveals certain patterns and potential reasons for the relative popularity of non-causal description in this journal as well. There are certainly subtypes within the non-causal descriptive articles published in Uluslararası İlişkiler. First, theoretical literature reviews and reassessments of key thinkers’ works constitute a very common subtype of non-causal articles, such as reassessments of Clausewitz[12] or the role of the discourse of anarchy in international relations theory.[13] As mentioned earlier, such review articles of the theoretical literature typically do not have a causal argument, and hence contribute to the large percentage of articles that are classified as having non-causal description in the current study. A second subtype of non-causal articles are descriptive historical works, such as the “negotiations of the 1826 Akkerman Treaty” between Russia and the Ottoman Empire[14] or the process of establishing the first permanent Polish embassy in Turkey.[15] These works often do not have, and do not attempt to establish, a causal relationship as their main argument. A third subtype of non-causal articles are reviews of teaching in international relations in Turkey, or less frequently, methodological exegesis akin to the current article.

A considerable number of articles based on “post-positivist” approaches to international relations[16] are also published in Uluslararası İlişkiler, which may explain, at least in part, why there are many articles in this journal that can be characterized as “non-causal description.” Even though some of the leading self-identified constructivists do not shy away from but rather embrace the goal of “explaining” as well as “understanding” in the study of international relations,[17] there are other scholars who explicitly identify two different kinds of international relations scholarship, one interested in causal “explanations” and the other interested in non-causal “understanding.”[18] As such, various forms of inquiry that are identified as reflectivist, interpretivist and/or hermeneutic approaches, may and often do eschew causal relationships of the kind reviewed in this article. Therefore, at least for some self-conscious adherents of such non-positivist approaches in international relations scholarship, producing articles investigating causal relationships is not a desirable (or possible) goal, and hence articles based on non-causal descriptions may not be seen as a social scientific weakness from such a vantage point.

6. Unpacking the Popularity of Global Warming: Interest in the Longue Durée or Imprecise Operationalization of Causal Variables?

Many social and political processes and their resulting outcomes indeed unfold over very long time periods, ranging from many years and decades to even centuries or more. Thus, it is not surprising that many social scientific puzzles have long term causes and long term outcomes. However, in the case of Turkish studies, an unfortunate reason as to why many articles seem to suggest a global warming type of causality is ambiguous, imprecise, and poor operationalization of the independent and the dependent variables. In other words, since many scholars fail to temporally specify and delimit their cause(s) and outcome(s), their purported causal explanations appear to have an unspecified, thus long-term, variables on both ends (cause and effect/outcome). Thus, many articles appear to have a Global Warming type of causality almost by default, that is, because of no clear operationalization or temporal specification of causal variables. This is a major methodological weakness, which has to be addressed and corrected for the improvement of the social scientific quality of Turkish studies. It is indeed remarkable that the Global Warming type of articles constitute an absolute majority of all articles published in Uluslararası İlişkiler, and are by far the most popular of type of article among the four types of causal articles published in Turkish Studies.

Instead of criticizing other scholars’ works for being responsible for the overrepresentation of Global Warming type of articles, I would rather acknowledge (or confess!) that I have also published articles in both of these journals since 2012 and both of my articles were also based on a Global Warming type of causality with long-term causes leading to outcomes that also unfold over the long-term. In trying to explain NATO’s eastward expansion, admittedly a long-term process, I argued in Uluslararası İlişkiler that a peculiar concatenation of domestic political (partisan) interests that endured for many years (at least for about a decade, roughly corresponding to 1994-2004) to be the cause of this significant geopolitical outcome, which is otherwise inexplicable from a neorealist perspective.[19] Writing in Turkish Studies three years later, I argued that the curious and rather unprecedented rise of pro-Russian Eurasianism as the “fourth style of politics” in Turkey from the late 1990s until the mid-2000s, which is at least a medium-term if not long-term outcome, is the result of other long-term structural changes, namely, the diminution of the Russian threat coupled with the rising perception of a threat from the United States, which coincided with the increasing popularity of Islamic political movement, also a long-term variable that is in part structural and in part agentic.[20] Thus, I also contributed to the general trend by publishing articles with a Global Warming type of causality in both Uluslararası İlişkiler and in Turkish Studies.

Just as in the case of subtypes of articles that are based on non-causal description, however, there are also subtypes of articles based on a Global Warming type of causality. At the most basic level, some articles, including mine, are self-consciously based on a long-term cause leading to a long-term outcome. This becomes apparent if and when the article states, as part of its main argument, the primary cause and the outcome of interest, and the temporal delimitation of each. To continue with my argument in one of the above mentioned articles for illustrative purposes, I try to explain NATO expansion, a temporally delimited outcome, with certain time-specific electoral and/or legislative cycles in American and Russian domestic politics in the 1990s.[21] Articles that are self-consciously based on long-term structural variables, such as economic development, seeking to explain other long-term developments, such as democratization, also fall under the Global Warming category,[22] unless they specifically focus on a narrowly time specific (such as a currency crisis or a trade embargo that occurred in a particular date) instance or aberration of otherwise structural variables. Another subtype of articles in this category, however, are classified as having a Global Warming type of causality because the purported cause(s) and/or outcome(s) in the article are not temporally delimited or specified, such that the reader (or the coder in the current study) cannot clearly understand or know when the cause begins and ends, and when the outcome begins and ends. This is a major methodological weakness that has to be addressed for the improvement of political science and international relations scholarship produced in and about Turkey. In short, scholars in the future, including the current author, should take care to specify the temporal delimitation of both their primary cause(s) and main outcome(s) of interest.

7. Meteorites: Precise Cause, or Attributing Too Much Explanatory Power to One Cause?

Compared to non-causal descriptive and Global Warming types of articles, the total number of the other three types of articles combined constitute a minority. To reiterate, what distinguishes Tornados, Meteorites, and Earthquakes from Global Warming is the existence of at least one short-term variable, whether as the main cause or as the main outcome. This necessitates special attention to the temporal specification of at least one of the two main (independent or dependent) variables. Such a specification arguably makes it more likely for such articles to have a better operationalization. After all, the necessity to temporally specify and narrowly define either the main cause and/or the main outcome in a purportedly causal relationship may motivate scholars to more explicitly focus on operationalization of variables. Nonetheless, as noted earlier, there is also an observable hierarchy in terms of the distribution of the three types of causality with either a short term cause and/or a short term outcome: Among the articles reviewed in this study, Meteorites are more common than Earthquakes, which in turn are more common than Tornados.

There are somewhat surprising number of studies with a Meteorite type of causality, based on a short term cause and a long term outcome. These are often works that attribute a major outcome, such as two decades of education policy under presidents Atatürk and İnönü, to particular person- and time-specific choices of one or a few members of the political elite.[23] Attributing major outcomes such as Turkey’s Kurdish identity politics to short-term electoral incentives in one electoral cycle would be another example. In fact, the articles that explain AK Party’s various policies with long-term consequences to very narrowly electoral or other self-interested motivations, or the personality of its leader(s), constitute the largest group of articles that can be categorized as having Meteorite type of causality in Turkish Studies. Finally, another subtype of Meteorite articles are those based on the explanatory power of a recent, surprising, and seemingly world-historical development. The most popular “event” that was the short-term cause of a large number of Meteorite type of articles in Uluslararası İlişkiler appears to be the Arab Spring. In fact, six of the twenty Meteorite type of articles, corresponding to 30 percent of all articles in this category in Uluslararası İlişkiler, had “Arab Spring” as their main causal variable.[24] Various kinds of revolutionary uprisings seem to have motivated articles with Meteorite type of causality, such as an article on the Young Turk revolution of 1908 and its impact on civil-military relations in the late Ottoman Empire.[25]

Upon closer inspection, it seems as if the Meteorite quality of the causality apparent in some of these articles is the result of attributing too much explanatory power to one cause, such as the impact of the crisis in Ukraine on Russia’s decades-long dispute with Japan over the Kuril islands,[26] or Turkish president Erdoğan’s “one minute” speech at Davos on the Turkish public’s perceptions of foreign policy.[27] However, from a methodological point of view, potential long-term causes of the outcome of interest should also be entertained as alternative explanations. Such diversity in temporal horizon of causality is desirable if not even necessary, unless the authors have a specific justification for temporally (and otherwise) limiting the alternative causal explanations that they seek to examine. This is a potential weakness that bedevils many of the articles purporting to have a Meteorite type of causality. For example, in an attempt to directly address this potential weakness, I published an article with an explicitly Meteorite type of causality seeking to explain the long-term Islamist and ethnic separatist challenges to the state in Turkey, Pakistan, and Algeria, where I entertained both long-term structural and short-term agentic causes.[28] One methodological precaution in employing any causal argument is to entertain the possibility that not only different causes but also different causes of varying temporal horizon (short- and long-term) may be responsible for the outcome of interest.

8. Earthquakes: Precision of the Outcome Encouraging Causal Process Tracing?

Earthquake type of articles based on long-term causes leading to short-term outcomes are somewhat few in Turkish Studies (30 out of 217), but certainly far fewer in Uluslararası İlişkiler (4 out of 149). The precision of the outcome (DV) in earthquake type of causality may encourage long-term process tracing as well as coming to terms with at least some alternative hypotheses for the same outcome. The short-term and specific operationalization of the outcome may keep the focus on causality throughout the analysis. The biggest puzzle that I pursued in my academic career so far, on which I published at least two articles[29] and a book,[30] was an “earthquake.” My outcome (DV) of interest was an instance of a historic change in ethnic policies of Germany (citizenship law of 1999), Russia (removal of ethnicity from internal passports in 1997), and Turkey (beginning of public broadcasting in minority languages in 2004), which, I argued, was the result of political historical (“tectonic”, if I were to use another metaphor from geology) changes that unfolded over approximately fifty years. In other words, I could operationalize my dependent variables of interest as processes that unfolded over a couple of years (at most a decade), whereas their causes unfolded over many decades, which is what made them “earthquakes” in terms of the temporal dimension of the underlying causal processes. While the change in the ethnicity regime was a transition that I explained through a causal theory, the tripartite typology that I developed to characterize the specific constellation of ethnic policies in different countries (monoethnic, antiethnic, and multiethnic regimes) can be considered as an exercise in constitutive causation, at least as it is defined by Alexander Wendt.[31]

Short-term outcomes, such as a constitutional or legislative act of national, regional or world-historical significance, keep you focused on the puzzle, the outcome, and this arguably makes it easier or at least possible for other scholars to follow-up with better or at least similarly focused explanations. Very narrowly time-specific outcomes, such as a parliamentary vote authorizing (or denying) declaration of war, or the passage of historic legislation such as expansion of voting rights to women and/or ethno-racial minorities, or the abolition of slavery or segregation, could be among numerous outcomes of significance that can be (and/or have already been) employed as dependent variables in Earthquake type of causal explanations. Most recently, just as the current piece went into production, I published another article in Turkish Studies based on a causal explanation that I explicitly identified as an Earthquake.[32]

9. Tornados: The Result of a Philosophical Reflection or Methodological Overdetermination?

In a complete reversal of the pattern found in American political science, Tornado type studies are the least common type of causality found in Turkish Studies. Those few articles with a Tornado type of causality, however, appear to be the result of a larger methodological choice. In short, articles using quantitative methods including inferential statistics overwhelmingly privilege a Tornado type of causality based on short term causes leading to short term outcomes. Thus, although the number of articles in this category is much smaller than that found in American political science, both the causes (methodological choice) and Pierson’s criticisms of a Tornado type of causality seem to apply to similar works in Turkish studies as well. Perhaps somewhat more surprisingly, not a single article with a Tornado type of causality has been published in Uluslararası İlişkiler during the six-year period reviewed in this study.

Studies based on public opinion surveys, exploring causal relationships between one attitude (such as fear of EU enlargement, or globalization)[33] and another (such as fear of further Turkish immigration, or perception of personal benefit from globalization)[34] constitute one subset of articles published based on a Tornado type of causality. The use of quantitative methods such as inferential statistics to demonstrate a causal relationship between variables drawn from public opinion surveys appears to be the primary reason these studies have a Tornado type of causality almost by default.

10. Problems of Operationalization: What is To Be Done about Measurement in Time?

At a very basic level, many of the problems related to the temporal dimension of causality found in all five types of articles (including non-causal description) in the field of Turkish studies are ultimately problems of operationalization and measurement. What could or should scholars do in order to overcome these problems?

At a minimum, one should start out with a clearly identifiable, temporally and spatially (geographically) delimited, preferably uncontestable empirical outcome. Perhaps the worst case scenario for a piece of work that aspires to be social scientific is not to have a clearly identifiable, observable, at least to some degree measurable, and uncontestable “outcome.” Unfortunately, such a “worst case scenario” is all too common not only in the field of Turkish studies but also in many other works of political science and international relations around the world. It is not at all unusual to find works where even the existence of the outcome (dependent variable) or the motivating puzzle of the study is highly debatable.

One reason for the prevalence of non-causal description in Turkish studies is the existence of many normative works seeking to judge social or political phenomena from an ethical or philosophical point of view. In such works, there is often no systematic attempt to explain or evaluate the causes of the phenomenon or phenomena of interest. Second, another reason for the prevalence of non-causal description is that there are also many speculative studies concerned with the future, that is, with outcomes that have not occurred, which may be expected and acceptable in policy relevant outlets and the mass media, but not to be expected or acceptable as much in academic publications.

Unless one has a very clear operationalization and measurement, and at least some very clearly identifiable micro-level causal mechanisms that are demonstrable or observable through sufficiently delimited (geographically, temporally, and/or in other ways) case studies, it would be wise to avoid Global Warming type of causality, because having both the main cause and the main outcome unfolding over very long periods of time risks introducing an unmanageable degree of fuzziness into the causal narrative.

Once the outcome and the cause(s) are clearly temporally delimited, whether our causal framework resembles a Tornado, Meteorite, Earthquake, or Global Warming will be implicitly apparent, but it is still better for the author to explicitly state whether the argument has, for example, a long-term cause that explains a short-term outcome, or vice versa, as I did in several of my works.[35] This would also demonstrate that the author is very well aware of the temporal dimensions of causal processes and is making a conscious decision in favoring one causal temporal type over others in explaining the outcome of interest.

11. Draw a Causal Graph

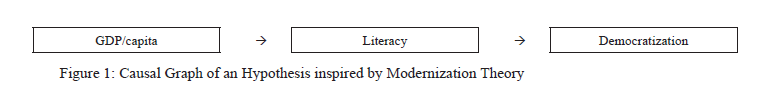

Following on the advice of David Waldner,[36] I currently require my students in our qualitative research methods course[37] to draw a causal graph of their argument, however rudimentary it (the argument or the drawing!) may be. Simply forcing oneself to draw a causal arrow linking the hypothesized cause(s), or independent variable(s), to the main outcome(s), or dependent variable(s), is an immensely fruitful intellectual and methodological exercise. At the very least, it forces the scholar to be clear about the hypothesized causal relationship and its two principal components, cause(s) and outcome(s) of interest. Drawing a causal relationship requires theoretical clarity, but it also forces the author and the audience (e.g., reviewers, readers, critics, etc.) to pay attention to conceptualization since the causal graph will necessitate labeling/naming each causal variable in a short form.

For purposes of illustration, I provide above a very crude version of an attempt at drawing a causal graph of a hypothetical relationship, inspired by Modernization Theory, whereby increasing income levels lead to increasing literacy, which in turn leads to democratization (Figure 1). In fact, this causal graph implies two different causal relationships in a causal chain, the first one positing higher income leading to higher literacy, and then another one positing higher literacy leading to democratization.

Drawing the causal relationship also forces the scholar to clarify whether the hypothesized relationship is based on a “chain” as in Figure 1 above, or the concatenation of two or three or more variables that are separately necessary but only together sufficient for the outcome,[38] or whether there is yet another type of causal configuration that leads from the causes to the outcomes.

12. Temporally Delimit The Hypothesized Cause(s) and The Outcome

In order to more fully address the temporal dimension of causality, another crucial step in proposing and conducting social scientific research is to temporally delimit the hypothesized cause(s) and the outcome(s) of interest as much as possible. Which year(s), month(s), or days(s) did the main outcome (dependent variable), the central puzzle, of the research design unfold? This question is absolutely central to the entire research endeavor. Without knowing at least approximately, and if possible exactly, the time interval in which the outcome “happened” or transpired is essential. Ultimately, the temporal delimitation of the outcome is a decision that the scholar has to make, but it has to be justified in a way to be convincing to the scholarly audience as well. For example, in the case of a piece of legislation, the scholar may choose to delimit the outcome as the day it was passed, or between the day it was proposed and the day it was passed, or between the day it was proposed and the day it came into force, or in any other way in which it seems justifiable to temporally delimit the passage of that legislation. If the outcome is seemingly an “event” such as a piece of legislation, beginning of a war, genocide, revolution, and the like, it may be somewhat easier to temporally delimit it. If the outcome is seemingly a “process” such as a years-long attempt to abolish slavery (emancipation) or end racial segregation, then it may make more sense to specify it as much as possible.

Which year(s), month(s), or days(s) did the main hypothesized causes, or potential independent variables, of the research design unfold? This is also an important question, but arguably secondary to the temporal delimitation of the outcome, since the outcome should be driving the entire research design, whereas the hypothesized causes are only of significance due to their potential explanatory power vis-a-vis the outcome. If the hypothesized cause is a structural or a cumulative variable, specifying the relevant time interval of an otherwise uninterrupted variable would be necessary, such as “change in GDP per capita between 1995 and 2005” in a causal relationship where GDP per capita is one of the hypothesized causes.

13. Self-Critical Introspection: Possibility of Multi-Temporal Equifinality?

Even after following all the steps in conceptualization, operationalization, and measurement with special attention to the temporal delimitation of dependent and independent variables, and having formulated an argument that has demonstrable advantages over the preexisting alternative explanations, scholars should leave the door open for the possibility of what I describe as “multi-temporal equifinality.” Equifinality is the possibility of different causal paths leading to the same outcome, and it has been discussed at length in seminal works on qualitative methodology in particular.[39] “Multitemporal equifinality”, I suggest, is the possibility of the same outcome having different short-term and long-term causes. In other words, scholars should be explicitly open about the possibility of the same outcome (dependent variable) having different short-term and long-term causes.

I explored the possibility of multitemporal equifinality in my work on two major outcomes of significance for Turkish politics, namely, the PKK’s declaration to end the ceasefire against Turkey in July 11, 2015, and the Gülenists’ failed coup attempt of July 15, 2016. In both cases, I pointed out that there are very short-term causes that most likely “triggered” the PKK’s[40] and the Gülenists’ decision to attack, such as the PYD’s consolidation of territorial control in northern Syria in June 2015 and the impending dismissals of Gülenist officers in the military (originally expected to take place in August 2016), respectively. However, there were also long-term causal processes, such as the gradual removal of segregationist measures against religious conservatives and ethnic minorities under AK Party governments, which made an ultimate all-out conflict between these illegal groups and the Turkish government very likely, although not inevitable.[41] In my article titled, “Why did the PKK declare Revolutionary People’s War in July 2015?”, I took special care to emphasize that I was mainly evaluating competing short-term causes, especially the most popular ones in the media. In a much longer article, I took special care to emphasize that I was focusing on more long-term, quasi-structural reasons behind the PKK’s all out offensive and the Gülenist coup attempt.[42] In short, one can uphold different short-term and long-term explanations for the same outcome, as long as one explicitly distinguishes between them and explicates the distinctive causal logic behind them. This, in short, is the peculiar kind of equifinality that I describe as multi-temporal equifinality.

14. From Here to Eternity?[43] Concluding Remarks on Causal Mechanisms across Time

An important first step for increased methodological rigour and causal clarity might be scholars’ self-awareness about the temporal dimension of causal processes. One of the goals of the current article has been “raising awareness” about the temporal dimension of causal processes with a short empirical survey on studies of Turkish politics. In the spirit of promoting best practices, I also proposed that scholars explicitly discuss, however briefly, the temporal dimension of the causes that explain their outcome of interest in their articles, which would further methodological and theoretical transparency across the scholarly community.

Some of the causal processes we are interested in as scholars of Turkish studies have probably already ended, such as the causes of the Ottoman Empire’s alliance with Imperial Germany in the Great War, or the causes behind Turkey’s adoption of etatism as its economic policy in the 1930s. However, there are other causal processes that have been unfolding for decades, and the results of which we have been observing and will likely observe in the near future. Furthermore, there are probably other causal processes of significance that have been unfolding over centuries if not millenia, providing general patterns and structuring the “grand questions” of humankind, supposedly “from time immemorial to eternity.” What scholars could do is to be aware of, and if possible explicitly state, just what kind of temporal horizon their own causal explanation has. Ideally, the ultimate goal should be, as the thought-provoking title of the journal All Azimuth[44] suggests, to approach the same puzzle from multiple directions or all angles, not just in terms of using diverse methodological and theoretical tools, but also in terms of employing multiple temporal lenses.

* The author would like to thank Ilgın Bahar Evcil and Idlir Lika for their research assistance, Ersel Aydınlı and Gonca Biltekin for organizing a workshop in which a previous version of this paper was presented, Egemen Bezci for his comments as the discussant in this workshop, and an anonymous reviewer for All Azimuth.

Akçadağ, Emine, and Elnur İsmayilov. “Ukrayna krizinin Rusya ve Japonya arasındaki Kuril Adaları sorununa etkisi.” Uluslararası İlişkiler 12, no. 48 (2016): 95–115.

Aktürk, Şener. “The Fourth Style of Politics: Eurasianism as a Pro–Russian Rethinking of Turkey's Geopolitical Identity.” Turkish Studies 16, no. 1 (2015): 54–79.

———. “NATO neden genişledi? Uluslararası ilişkiler kuramları ışığında NATO’nun genişlemesi ve ABD–Rusya iç siyaseti.” Uluslararası İlişkiler 9, no. 34 (2012): 73–97.

———. “One Nation under Allah? Islamic Multiculturalism, Muslim Nationalism And Turkey’s Reforms For Kurds, Alevis, and Non–Muslims.” Turkish Studies 19, no. 4 (2018): 523–51. doi: 10.1080/14683849.2018.1434775.

———. “Passport Identification and Nation–Building in Post–Soviet Russia.” Post–Soviet Affairs 26, no. 4 (2010): 314–41.

———. “Regimes of Ethnicity: Comparative analysis of Germany, the Soviet Union/post–Soviet Russia, and Turkey.” World Politics 63, no. 1 (2011): 115–64.

———. Regimes of Ethnicity and Nationhood in Germany, Russia, and Turkey. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

———. “Religion and Nationalism: Contradictions of Islamic Origins and Secular Nation‐Building in Turkey, Algeria, and Pakistan.” Social Science Quarterly 96, no. 3 (2015): 778–806.

———. “Turkey’s Civil Rights Movement and the Reactionary Coup: Segregation, Emancipation, and the Western Reaction.” Insight Turkey 18, no. 3 (2016): 141–67.

———. “Why Did the PKK Declare Revolutionary People’s War in July 2015?” POMEPS Contemporary Turkish Politics, November 29, 2016. Accessed December 16, 2017. https://pomeps.org/2016/11/29/why–did–the–pkk–declare–revolutionary–peoples–war–in–july–2015/.

Ari, Başar. “Religion and Nation–Building in the Turkish Republic: Comparison of High School History Textbooks of 1931–41 and of 1942–50.” Turkish Studies 14, no. 2 (2013): 372–93.

Aslantaş, Selim. “Osmanlı–Rus ilişkilerinden bir kesit: 1826 Akkerman Andlaşması'nın müzakereleri.” International Relations/Uluslararasi İlişkiler 9, no. 36 (2013): 149–69.

Aydin, Umut. “Who is Afraid of Globalization? Turkish Attitudes toward Trade and Globalization.” Turkish Studies 15, no. 2 (2014): 322–40.

Bennett, Andrew, and Jeffrey T. Checkel eds. Process Tracing: From Metaphor to Analytic Tool. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Erdoğan, Emre. “Dış politikada siyasallaşma: Türk kamuoyunun “Davos Krizi” ve etkileri hakkındaki değerlendirmeleri.” Uluslararası İlişkiler 10, no. 37 (2013): 37–67.

George, Alexander L., and Andrew Bennett. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005.

Goertz, Gary. Multimethod Research, Causal Mechanisms, and Case Studies: An Integrated Approach. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017.

Hanioğlu, M. Şükrü. “Civil–Military Relations in the Second Constitutional Period, 1908–1918.” Turkish Studies 12, no. 2 (2011): 177–89.

Hinnebusch, Raymond. “The Arab Uprising and the MENA Regional States System.” Uluslararası İlişkiler 11, no. 42 (2014): 7–27.

Hollis, Martin, and Steve Smith. Explaining and Understanding International Relations. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990.

Karaosmanoğlu, Ali L. “Yirmibirinci yüzyılda savaşı tartışmak: Clausewitz yeniden.” International Relations/Uluslararası İlişkiler 8, no. 29 (2011): 5–25.

Katznelson, Ira. “Periodization and Preferences: Reflections on Purposive Action in Comparative Historical Social Science.” In Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social Sciences, edited by James Mahoney and Dietriech Rueschemeyer, 270–304. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Mahoney, James, and Dietriech Rueschemeyer, eds. Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social Sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Pierson, Paul. “Big, Slow–Moving, and… Invisible: Macrosocial processes in the study of comparative politics.” In Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social Sciences, edited by James Mahoney and Dietriech Rueschemeyer, 177–207. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Pierson, Paul. Politics in Time: History, Institutions, and Social Analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Smets, Kevin. “‘Turkish Rambo’ Going Transnational: The Polarized Reception of Mainstream Political Cinema among the Turkish Diaspora in Belgium.” Turkish Studies 15, no. 1 (2014): 12–28.

Tekindor von zur Mühlen, Sevinç. “Korean War in the Turkish Press.” Turkish Studies 13, no. 3 (2012): 523–35.

Topaktaş, Hacer. “Polonya'nın Türkiye'deki ilk daimi elçiliğinin kurulma süreci: Tarihsel dinamikler.” International Relations/Uluslararası İlişkiler 11, no. 43 (2014): 105–25.

Wendt, Alexander. “On Constitution and Causation in International Relations.” Review of International Studies 24, no. 5 (1998): 101–18.

Yalvaç, Faruk. “Uluslararası ilişkiler kuramında anarşi söylemi.” International Relations/ Uluslararası İlişkiler 8, no. 29 (2011): 71–99.

Yavcan, Başak. “Public Opinion toward Immigration and the EU: How are Turkish Immigrants Different than Others?” Turkish Studies 14, no. 1 (2013): 158–78.

Yıldız, Necip. “The Relation between Socioeconomic Development and Democratization in Contemporary Turkey.” Turkish Studies 12, no. 1 (2011): 129–48.