Giles Scott-Smith

Leiden University

This article critically explores some of the evaluative perspectives and models developed by social science scholars in order to further critical thinking on the function of exchange programmes, and particularly Fulbright, within international relations. It takes the concept of ‘educational exchange’ to mean the movement of individuals or groups between nations for the purpose of training of some kind, ranging from high school visits to professional skills. The Fulbright programme covers both student and scholar exchange and has the added element that academics are moving also to teach, taking their expertise with them. While there are many studies of bilateral exchange programmes, there is more to explore in terms of the function of educational exchange as a vector of transfer (be it of knowledge, material, people, or all three) in transnational or international history. The article first surveys the literature on the Fulbright programme to assess how its purposes in international relations have been presented. It then explores potentially innovative ways to conceptualise exchanges in international and transnational interactions: ‘geographies of exchange,’ ‘brain circulation,’ ‘centres of calculation,’ ‘enlightened nationalism,’ and ‘parapublics’.

1. Introduction

It is a widespread assumption that cross-border exchanges contribute to a more peaceful international environment by undermining stereotypes and establishing social ties. As Julie Mathews-Aydinli summed up in a recent book exploring this theme, “Intuitively, it seems logical that educational exchanges will increase participants’ knowledge and understanding of others’ practices and beliefs, and this will in turn contribute to better, friendlier relations between the participants and those others.” [1] The Fulbright program is presented as typical of this outlook, as its website announces:

Through our unique international educational and cultural exchange programs, Fulbright’s diverse and dynamic network of scholars, alumni and global partners fosters mutual understanding between the United States and partner nations, shares knowledge across communities, and improves lives around the world.[2]

Behind this general statement of intent lies the assumption that Fulbright, through its facilitation of international, inter-cultural, and educational exchange, creates the basis for the progression of inter-state relations in a more peaceful direction. Of course, these kinds of claims have not avoided criticism. Some researchers have found the presumptions of exchanges overtly idealistic in their goals, often at variance with the available data on their results.[3] Attempts to quantify the positive impact of exchanges can also appear lacking in depth, although survey development has led to increasing refinement of results.[4] There is also a sense that a counter-trend is evolving, whereby we are returning to a situation of public diplomacy increasingly being used as a tool in an environment of competing states, rather than an investment in a more enlightened, post-national landscape.[5]

This article critically explores some of the evaluative perspectives and models developed by social science scholars in order to further critical thinking on exchange programmes, and particularly Fulbright, within international relations.[6] It takes the concept of ‘educational exchange’ to mean the movement of individuals or groups between nations for the purpose of training of some kind, ranging from high school visits to professional skills. The Fulbright programme covers both student and scholar exchange and has the added element that academics are moving also to teach, taking their expertise with them. While there are many studies of bilateral exchange programmes,[7] there is more to explore in terms of the function of educational exchange as a vector of transfer (be it of knowledge, material, people, or all three) in transnational or international history.[8] Global history and studies of hegemonic or imperial networks have occasionally focused on the contribution of exchanges for the establishment and/or maintenance of trans-continental connections, in particular in the context of Pan-Americanism.[9] As Paul Kramer presciently put it in 2009:

the history of foreign student migration ought to be explored as U.S. international history, that is, as related to the question of U.S. power in its transnational and global extensions. In this sense, my argument here is topical: that historians of U.S. foreign relations might profitably study international students and, in the process, bring to the fore intersections between “student exchange” and geopolitics.[10]

To date, this (re)positioning has not yet been done for the Fulbright programme, yet the intersections of the programme’s global scope and purpose with US global power after WWII are more than evident. With this as context, this article first surveys the literature on the Fulbright programme to assess how its purposes in international relations have been presented. This is followed by a section on recent analytical pathways from the social sciences that provide potentially innovative ways to conceptualise exchanges in international and transnational interactions: ‘geographies of exchange’, ‘brain circulation’, ‘centres of calculation’, ‘enlightened nationalism’, and ‘parapublics’. This is followed by a discussion of the ways in which these perspectives might be brought to bear in investigating the contribution of exchanges as channels of influence in international relations over time.

2. The Purposes of the Fulbright Programme

The Fulbright program, of course, stems from humble beginnings that did not provide much indication of the initiative’s expansive goals. The amendment to the Surplus Property Act of 1944 that provided the means for what would become the global network of Fulbright agreements is a very plain, almost anodyne piece of legislation. Regarding the purpose of the Act, the following is laid out in concrete terms:

This “ingenious marriage of necessity and idealism” reflects a piece of legislation that was inserted in a way to deliberately avoid attention and opposition, flying under the radar during the quiet summer period of the congressional calendar.[12] Fifteen years later, the preamble to the Mutual Educational and Cultural Exchange Program (Fulbright Hays) is much more explicit as to the grand aims involved:

The purpose of this chapter is to enable the Government of the United States to increase mutual understanding between the people of the United States and the people of other countries by means of educational and cultural exchange; to strengthen the ties which unite us with other nations by demonstrating the educational and cultural interests, developments, and achievements of the people of the United States and other nations, and the contributions being made toward a peaceful and more fruitful life for people throughout the world; to promote international cooperation for educational and cultural advancement; and thus to assist in the development of friendly, sympathetic, and peaceful relations between the United States and the other countries of the world.[13]

This is the language we most associate with the overall goals of the Fulbright exchanges: pursuing educational advancement, achieving mutual understanding, seeking cultural unity, and as a result promoting the cause of peace. It is the kind of language that Robin Winks (1952 Fulbright grant to New Zealand) dismissed in the opening sentence of an essay on the subject – “One’s thoughts about the value of the Fulbright experience invariably consist of a tissue of clichés” – before concluding: “A tissue of clichés it is. But no less true for that” .[14]

The belief that cross-border contacts could gradually break down social and political barriers and lead to a more peaceful international system, if not a transformation of international society, is a staple of Enlightenment Liberal thinking. Free trade was, from this perspective, meant not only to generate wealth but also to facilitate economic interdependence, social interaction, and the generation of a shared sense of common human destiny. Kant’s notion of ‘perpetual peace’ from 1784 comes closest to embodying this as a cosmopolitan political project.[15] Yet the inauguration of organized exchanges in the Atlantic and imperial worlds in the late 19th and early 20th centuries occurred during a peak period of nation-building and competitive interests, and “organizing the mobility of elites for scientific and economic gain became an instrument of foreign policy.” [16] So whereas Liberalism provided the broad theoretical assumptions underlying cross-border contacts as a fundamental good, the actual implementation or organized exchanges in the form of scholarships for training and educational purposes always possessed a kernel (or more) of national interest. But the positive sentiments of Liberalism based on human nature and the wish to bring a new world into existence always fed more easily into the public posture of exchanges. International organisations, looking to evolve the state system beyond competition towards cooperation on shared issues and recognition of shared values, took this all a stage further. Karl Deutsch’s ideal of a ‘security community’, the democratic peace theory, paths to functionalist integration, and the role of communications in transforming inter-state relations all built on these assumptions to construct Liberal-fuelled imaginaries of peaceful future worlds through normative, value-rich processes of integration.[17]

Many studies of the Fulbright programme have embarked from these fundamental Liberal assumptions and the belief that it was contributing to the evolution of international relations in a positive direction. These approaches thus praise the Fulbright concept not as a normative but as a transformative power. Reviewing the legacy of Fulbright exchanges for the contribution they could make at the dawn of the post-Cold War era, Leonard Sussman exclaimed the following in resounding rhetoric:

The small world of Fulbrighters can make limitless connections with the large universe. One man launched that idea. It has improved hundreds of thousands of lives directly, millions indirectly. That idea has helped introduce entire scholarly disciplines in countries abroad, and has led to better teaching and research methods here and abroad. It has improved the way architects build, scientists research, teachers teach. The idea has influenced the way countries act: Their behavior improves as elites learn greater sensitivity and act with greater respect for other cultures. That idea has brought people together from many nations not just for a semester, but a lifetime.[18]

It would be too easy to compartmentalize this as more of Winks’ ‘tissue of clichés’. At the heart of this worldview lie two fundamental assumptions: that the programme has generated an exclusive elite devoted to the betterment of the world through public service and inter-cultural communication; and that Fulbright is all about the transfer of expertise through as much the camaraderie of inter-personal relations as the formality of professional appointments. This situates the ethos of the programme in the same context as, say, the Rotary club movement, that during the first half of the twentieth century spread the ideals of business-related brotherhood just as Fulbright spread the ideals of academia-based brotherhood in the second.[19]

Yet Fulbright the politician and Fulbright the programme did possess their own in-built limitations to realizing this one-worldist vision. Firstly, there has always been a Liberal-Realist dichotomy at the heart of the Fulbright exchange ideal. Sam Lebovic has outlined how Senator Fulbright himself took for granted the underlying assumptions of the benefits of exchange, talking only in general terms along the lines of the Fulbright-Hays preamble above. For Fulbright, the values inherent in these exchanges were simply a given – they were a normative force to gradually steer international society towards a better future. That future represented the effective merging of American values as universal values, of the American interpretation of civilization as world civilization, so much so that Lebovic concludes that “For all the talk of mutual understanding, in other words, Fulbright imagined that educational exchange would produce a global elite that was attuned to American values and American interests and would work to remake their countries in the image of American freedom.” [20] Fulbright’s elitism is clear – and for a Rhodes Scholar, almost to be expected – in that by directing attention to the carefully selected ‘best and the brightest’ a potential new era of international accord, led by the enlightened few and with the US acting as lodestar, could be achieved. Fulbright himself, in the preface to a special issue devoted to the programme in 1987, laid this purpose out clearly:

I do not think it is pretentious to believe that the exchange of students, that intercultural education, is much more important to the survival of our country and of other countries than is a redundancy of hydrogen bombs or the Strategic Defense Initiative. Conflicts between nations result from deliberate decisions made by the leaders of nations, and those decisions are influenced and determined by the experience and judgement of the leaders and their advisors. Therefore our security and the peace of the world are dependent upon the character and intellect of the leaders rather than upon the weapons of destruction now accumulated in enormous and costly stockpiles.[21]

This ‘national internationalism’ was regularly stated in official documents as well, where the confluence of US and global interests was taken as a given. The Board of Foreign Scholarships could thus refer without contradiction to how “The Fulbright program is a model of investment in long-term national interests. By building goodwill and trust among scholars around the world, it has created a constituency of leaders and opinion-makers dedicated to international understanding.” [22] The Fulbright concept therefore fitted perfectly within what John Fousek referred to as the ‘nationalist globalism’ of the post-WWII period:

President Truman’s public discourse continuously linked U.S. global responsibility to anticommunism and enveloped both within a framework of American national greatness…. This discursive (and ideological) triad of national greatness, global responsibility, and anticommunism pervaded American public life in the later 1940s.[23]

Lebovic argues that this nationalist undertone was a built-in part of Fulbright’s own ideology – just as the (US-)educated elites around the world should lead their respective countries, so too did the US have the responsibility to provide the guidance for those elites as leader of the ‘free world’.

The fact that the programme was reliant on appropriations from Congress following the Fulbright-Hayes Act of 1961 also meant that arguments needed to be made in the context of national interest to secure the necessary political support. Pressures to quantify Fulbright’s ‘value’ for furthering USA foreign policy interests gradually increased from the late 1960s onwards, when the State Department and USIA began to adopt ‘cost effective’ validation rubrics similar to the Defense Department.[24] Yet since the very beginnings of the Fulbright programme, voices from the academic world called for its use-value to be understood in terms different from those used in other arms of foreign policy. As Francis Young stated clearly around the time that calls for quantification began to increase:

Perhaps one reason we have not supported the exchange program more generously is that we have expected the wrong things of it, have assigned it a short-range, foreign policy back-up role, and then wondered why it did not produce the hoped-for results. Were we to see educational exchanges in their proper relationship to foreign policy – as extending the range of diplomacy, improving the climate in which it functions, and placing it on a firmer information base – we would recognize the importance of the Fulbright-Hays program more fully, use it to better advantage, and support it more generously.[25]

Over the years, and especially following the departure of Fulbright himself from the Senate in 1972, respect for exchanges as a form of ‘slow media’ functioning in their own time zone has waned, and the demand for statistical evidence of effectiveness has grown. The US State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs has posted a series of evaluation studies dating from 1997 onwards, including several on the Fulbright student, scholar, and teacher programmes. The data is overwhelmingly positive in tone, but the level of the evidence presented is strikingly thin.[26]

Fulbright’s elitist outlook also shaped the purposes of the programme in terms of race and gender, which raises questions about its role as an emancipatory force. A member of the social upper class representing a Southern state in Congress, Fulbright the representative and Fulbright the senator were very much in line with the racial prejudices of their socio-political milieu. It is worth mentioning in stark detail Fulbright’s record on civil rights:

J. William Fulbright maintained a perfect anti-integration voting record in Congress from his first election to the House in 1942 until 1970, when he first deviated from the segregationist line with his vote to extend the Voting Rights Act [VRA]. Prior to that moment of personal history, he voted against the Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1960, 1964 and 1968, and against the Voting Rights Act of 1965. He was an active participant in various filibusters of nondiscrimination legislation between 1948 and1964, and signed the Southern Manifesto of 1956. His only betrayal of the segregationist position was when he declined to join the doomed filibuster of the 1965 Voting Rights Act (VRA), even though he voted against it on final passage. When the VRA was up for reauthorization in 1970, and Fulbright confronted for the first time an electorate with large numbers of black voters, he cast his only pro-Civil Rights vote in over three decades. Otherwise, the Arkansas statesman stood with staunch segregationists such as James Eastland of Mississippi and Richard Russell of Georgia.[27]

With this outlook, it is logical that Fulbright himself was not so interested in pursuing the exchange programme with nations of the Global South, although the imperatives of US foreign policy, combined with the availability of surplus military hardware to sell, soon guided it down exactly that path. Thus, the first Fulbright agreements were signed with China in 1947 and Burma, the Philippines, and Greece in 1948.[28]

On the issue of gender, the programme was more positive in its impact. Reviewing the relevance of gender in the working and impact of the programme, Molly Bettie has argued that it was open to female participants from the start and that the first appointments to the Board of Foreign Scholarships included professors Helen White (University of Wisconsin), Sarah Gibson (Vassar College) and Margaret Clapp (Wellesley College).[29] Nevertheless, social conservatism still reigned regarding gender roles in the US, and during the first years women were only making up one-third of Fulbright student grantees.[30] Most female participants from the US were white, middle class, and travelling to Europe. Senator Fulbright was also not in favour of extending the scope of the senior scholar grants to allow their dependents (generally referring to their wives) to travel with them, despite the many reports that indicated the additional positive influence of family members in interactions with local communities. For Fulbright, the research grants for scholars should remain focused on academic excellence. Since this assumed that most individuals able to attain academic excellence were men, it is indicative of Fulbright’s own understanding of gender hierarchy and the purpose of the exchange experience.

Over the years, studies of the impact of the Fulbright programme in national contexts have gradually increased, as the available data and access to archives has allowed for more detailed assessments.[31] These studies have built up a mosaic image of US global influence over time, taking the knowledge/power nexus as its core and liberal internationalism as its motif.[32] Moving beyond anecdotes, these studies have brought the Fulbright programme slowly into focus as a key vector of influence around the world, shaping the production and dissemination of knowledge across the humanities, social sciences, and applied sciences, with the United States functioning as the principal resource centre. With these studies providing an expanding foundation for further research, it is apposite to consider how we can still further the workings of this knowledge/power nexus. The following section will explore a series of analytical pathways that can be used to assess the Fulbright programme anew: ‘geographies of exchange’, ‘brain circulation’, ‘centres of calculation’, ‘enlightened nationalism’, and ‘parapublics’.[33]

3. Geographies of Exchange

Geographers have contributed a whole new perspective to the spatial significance of exchange, mapping out the circulations of knowledge in the context of broader matrixes of power on a global scale. From this perspective, exchanges become “an instrumental strategy to shape cosmopolitan identities, through transnational connections and the patronage of particular disciplines and scholars.” [34] Focusing attention on the role of the Ford Foundation in India during the early Cold War, Chay Brooks has sketched how the Foundation’s ‘modernist imaginary’ was transferred as a form of symbolic power to Indian individual and institutional beneficiaries. At the heart of this was a desire, indeed a belief system, that “educational philanthropy was an investment in a better functioning political order” :

Technical exchanges were about providing an experience allied to the transferral of expert knowledges acquired through American-led instruction. The administration of exchange acted as a means to converge the universal knowledge of scientific practice, the local knowledges of farms in the United States, as well as the travelling knowledges of the Indian extension workers. The apparatus of exchange formed a line of connection, a form of scalar geopolitics, between the philanthropic and educational imperatives in the boardrooms of America, and its mutation into new ‘modern’ and ‘developed’ forms of farming and village life.[35]

Brooks adds another perspective to the notion of exchanges acting as a form of ‘capillary power’ on a global-local scale, through which knowledge would be transferred, largely in a one-way direction.[36] The ‘modernist imaginary’ was in practice the deliberate imposition of hierarchies of knowledge based on a fixed understanding of ‘development’, with local knowledge and practices either subordinated or erased from the narrative as merely ‘primitive’. This situates the Fulbright programme firmly as a vector of US-led modernization, and Fulbrighters as the messengers of progress. On the mundane level, Fulbright was used to transfer knowledge and expertise in the natural and social sciences as a means to shape disciplines and educational training methods abroad. But Brooks is pointing beyond this to how modernist imaginaries generated in the metropole needed to be communicated and turned into reality in the periphery through the personal relations of Fulbright’s knowledge emissaries.

The fact that the Fulbright programme worked through bilateral committees is a crucial additional detail. The purposes of the programme in each national setting were mapped out by local representatives in conjunction with US members (both foreign service officers and civilians, usually from business and academia). This frames the programme – particularly from the 1960s onwards when local funding began to match and even surpass the US appropriations – more as a form of co-produced or ‘consensual hegemony’, a site of negotiation where the interests of national and US internationalist elites merge.[37]

4. Brain Circulation

The term ‘brain circulation’ was introduced into migration studies to conceptualise the significance and longer-term impact of temporary movements of highly skilled professionals.[38] It was Heike Jöns who took this as a model to explore “the long-term effects of the transnational circulation of academics and its meaning for the constitution of transnational knowledge networks.[39] By carrying out an in-depth study of the Humboldt Foundation’s academic grants over a period of 56 years, involving over 1800 visiting academics to (West) Germany from 93 countries, Jöns convincingly showed how the Humboldt’s targeted patronage of top-level academics in specific fields of activity unquestionably assisted with the scientific rehabilitation of post-war West Germany into professional transnational academic networks. The cumulative effects were evident in the (re-)establishment of German centres of knowledge production and the securing of expertise, contacts, and material resources. Drawing on Welch, Jöns concluded in agreement that exchanges such as Humboldt and Fulbright “are important mechanisms to sustain internationalization.” [40]

This research is important for its scope beyond the national setting. Fulbright internationalism was about linking scholars across national domains, setting up transnational connections with the United States functioning as the central node for patronage, inspiration, expertise, and sources. Drawing on Jöns' approach, the contribution of the various Fulbright programmes across Western Europe for the shaping and sustaining of the social sciences and business administration as academic fields can be further analysed.[41] American Studies is a case in point, not being a recognized field in Europe in the immediate post-WWII period, yet vital in terms of orientating academic production, learning and circulation around the US metropole. American power needed its interpreters, and they in turn needed access to America, Americans, and ‘Americana’.[42] Sites of exchange such as the Salzburg seminar, operating since 1947, acted as key centres of circulation for this development. Salzburg’s annual conference acted as a guiding event regarding the latest academic trends, shaping through debate the directions taken by the academic field.[43] Needless to say, Fulbright grantees figured prominently in this process as the principal guides, both through academic status and disciplinary insight.[44]

5. Centres of Calculation

A centre of calculation, as formulated by philosopher of science Bruno Latour, refers to a site where knowledge production takes place through the gathering of resources from other locations.[45] Centres thus function as central nodes within circulatory movements of experts, their congregation over time resulting in the building and the shaping of research fields and scientific disciplines. Such centres can function at all levels of activity, starting from the individual and moving up through various scales of the institutional. Commenting on the essential factor of mobility for the creation and sustenance of each centre, Jöns outlined it thus:

Scientists use encounters with other people and spatial contexts systematically in order to gather new resources for the production and support of their arguments. Depending on the field of study and period of time, the mobilized research objects, infrastructure and expertise may include documents, books, data, instruments, machines, methods, stones, plants, animals, people, specimen, artefacts, questionnaires, diaries, observations, maps and drawings as well as research assistants and collaborators.[46]

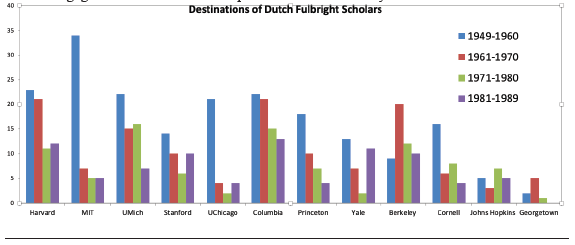

The centre model is useful for understanding the processes of knowledge accumulation, and its consequences, within the context of imperial ‘discovery’ and expansion. Recent studies have delved into the mechanisms of mobility and the centres around which and through which this mobility occurs, with organized educational exchange being a pivotal vector.[47] In this context, the Fulbright programme has had multiple shifting centres, depending on the disciplinary and institutional paths taken by the student and scholar grantees themselves. In terms of the United States, a small example can be given as to how Fulbright scholars from the Netherlands moved away from the centres of expertise among the elite universities over time to engage more with other sites spread across the country.

Outside of the United States, Fulbright scholars may contribute to the accumulation of knowledge in specific sectors, but they may also simply represent forms of academic capital that indicate ongoing symbolic ties with the US metropole.[48]

6. Parapublics

In an extensive study of Franco-German relations, Ulrich Krotz developed the notion of ‘parapublics’ as providing an often-hidden layer of intensive interaction. Defining them as “neither strictly public nor properly private,” Krotz outlined the characteristics:

Parapublic underpinnings are reiterated interactions across borders by individuals or collective actors. Such interaction is not public-intergovernmental, because those involved in it do not relate to each other as representatives of their states or state-entities. Yet, these contacts are also not private, because the interaction is to a significant or decisive degree publicly funded, organized, or co-organized….Parapublic underpinnings are a distinct type of international activity.[49]

Krotz focused specifically on youth exchanges, city and town ‘twinning’, Franco-German societies, and media. Materially, they provide resources and so encourage behaviour through patronage. Collectively, these activities “produce and reproduce a certain kind of personnel” and “generate and perpetuate social meaning and purpose, that is, they construct international value.” But the real value of Krotz’s work comes from his conclusion that the results were in important ways limited. There developed no Franco-German public sphere of any merit, and “French and German domestic social compacts” and separate social spheres remained largely intact. The parapublic channels instead functioned to normalize existing inter-state relations rather than generate some kind of novel sense of collective identity or alteration of political processes. The value of these channels comes from their social purpose and processes of normalization being institutionalized in inter-state relations. They contribute, in other words, to a sense of order in international affairs.

To an extent, Fulbright exchanges also contribute to such an outcome. The focus here is on the normative power of repeated cultural interactions, something that the existence of bilateral Fulbright committees necessarily facilitates as their raison d’etre.[50] Fulbright agreements are also parapublic, with grantees being designated as informal ‘cultural ambassadors’ operating outside of diplomatic channels. The sense of order refers to the assumption, on some level, of alignment with the interests and assets of the United States, be that political, economic, or cultural-intellectual, even if this is unquestionably combined with the intention of national gain. Despite functioning on an elite level, Fulbright exchanges are therefore also a form of normalization – a sign that bilateral relations are stable enough for a joint investment in academic endeavours and integrated futures.

7. Enlightened Nationalism

The notion that increasing cross-border contacts necessarily break down national cultural barriers and propel the creation of an ‘international community’ is a truism for the standard ‘Fulbright ideology’ discussed above.[51] Since “educational exchange [is] one of the main types of cross-border contact favored by theorists of international community,” Calvert Jones set out to test its assumptions by means of a detailed study of US students who had studied abroad. Based on a cohort of 571 students, Jones concluded that there was no recognizable sense of ‘international community’ being generated (i.e. changing perceptions of cultural affinity), but that the experience did cause a positive reduction in the perception of threat. In contrast to this, the study experience did heighten the sense of national identity and difference, if not something of a chauvinistic pride. This caused a questioning of the basic criteria for ‘international community’, but in a way that merged Liberal and Realist suppositions.

Perhaps a different conception of international community is needed, one that relies less on the realization of fundamental similarities, shared outlooks, and the warmth of human kinship – Hedley Bull’s “common culture of civilization” , Deutsch’s “we-feeling” – and more on the conviction that cultural differences may be profound but need not be threatening…..The idea of community, then, would be more akin to earlier classic liberal perspectives emphasizing civility and tolerance than to more recent understandings of international community that draw from social psychology and emphasize the growth of a shared identity or common culture.[52]

Jones concludes that a form of “enlightened nationalism” may be the most striking outcome, where “cross-border contact may indeed encourage peace-promoting norms and a sense of community, just not through the generation of a shared identity.” This claim carries on neatly from the parapublics of Kotz, downgrading expectations as to the outcomes of educational exchange, but at the same time re-directing attention to the normative power of these forms of cultural interaction over time. At the same time, it diverges from the ‘global club’ mentality of Fulbrighters, and neither can it contribute to understanding the social significance of their alumni associations.

8. Conclusion

These five approaches provide a cross-section of methods that can be used to move our understanding of the influence of the Fulbright programme on the international system beyond the ‘tissue of clichés’. Personal relations remain at the centre of its method, but the key lies in situating these relations within economies of exchange that reveal the wider power relations at work. Orthodox understandings of the Fulbright programme’s normative power rarely moved beyond how these interpersonal relations were meant to generate a global community of enlightened professionals.

Geographies of exchange situates the purpose of these interactions within a spatial matrix of power, with the United States at its centre. While this would fit the Fulbright’s administrative outlook during the first two decades after WWII, the evolution of the respective bilateral agreements into an increasingly shared enterprise from the 1960s onwards (to the point today where the US is a minority shareholder in many significant cases) points to the need for a framework that can take this mutuality into account. This in no way dislocates Fulbright from networks of American power – it in many ways strengthens the claim of hegemonic relations being mutually supportive between allies – but instead expands its meaning to include the symbolic capital of its modernizing emissaries.

Both brain circulation and centres of calculation are useful concepts for encapsulating the contribution of Fulbright exchanges over time in the establishment and stabilization of sites of disciplinary expertise with transnational influence. Here the contribution of global circulations for the solidification of the US position as ‘knowledge metropole’ can be further explored. In contrast, the concepts of parapublics and enlightened nationalism move away from the transformative power of an elite-based analysis to emphasise instead the normative contributions of cultural and educational exchanges on a mundane level, where the focus lies more on their contribution to ‘managing the system’ than ‘changing the system’. But power relations are not absent here either, since perpetuating the status quo is also perpetuating existing hierarchies of status and influence. Each of these pathways, by grounding and carefully framing the study of educational exchange, therefore provide the basis for analysing the Fulbright programme’s contribution to knowledge transfer, institution-building, and inter-national relations. Behind the soaring rhetoric of the Fulbright-Hays Act and Fulbright ideology as a whole, therefore, lies a field of research that still needs to be fully mapped out.

Ackers, Louise. “Moving People and Knowledge: Scientific Mobility in the European Union.” International Migration 43 (2005): 99–131.

Adi, Hakim. West Africans in Britain, 1900–1960: Nationalism, Pan-Africanism, and Communism. London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1998.

Adler, Emmanuel, and Michael Barnett. Security Communities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Allen, Neal. “The Power of the One-Party South in National Politics: Segregation in the Career of J. William Fulbright.” In Brogi, Scott-Smith and Snyder, The Legacy of J. William Fulbright, 32–45.

Arndt, Richard, and David Lee Rubin, eds. The Fulbright Difference: 1948-1992. New Brunswick: Transaction, 1993.

Bettie, Molly. “Fulbright Women in the Global Intellectual Elite.” In Brogi, Scott-Smith and Snyder, The Legacy of J. William Fulbright, 181–98.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. London: Routledge, 1984.

———. “ The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Capital, edited by J. Richardson, 241–58. New York: Greenwood Press, 1986.

Braithwaite, Lloyd. Colonial West Indian Students in Britain. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 2001.

Brogi, Alessandro, Giles Scott-Smith, and David J. Snyder. The Legacy of J. William Fulbright: Policy, Power and Ideology, Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2019.

Brooks, Chay. “‘The Ignorance of the Uneducated’: Ford Foundation Philanthropy, the IIE, and the Geographies of Educational Exchange.” Journal of Historical Geography 48 (2015): 36–46.

Bu, Liping. Making the World like Us: Education, Cultural Expansion, and the American Century. Westport, CT: Prager, 2003.

Cook, Donald. A Quarter-Century of Academic Exchange. Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago, 1971.

Deresiewicz, William. “ Faux Friendship.” Chronicle of Higher Education, December 6, 2009. https://www.chronicle.com/article/faux-friendship/.

Deutsch, Karl. Political Community and the North Atlantic Area: International Organization in the Light of Historical Experience. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1957.

Engerman, David C. “Bernath Lecture: American Knowledge and Global Power.” Diplomatic History 31, no. 4 (2007): 599–622.

Erbsen, Heidi. “The Biopolitics of International Exchange: International Educational Exchange Programs – Facilitator or Victim in the Battle for Biopolitical Normativity?” Russian Politics 3 (2018): 68–87.

Fischer, Yael. “Measuring Success: Evaluating Educational Programs.” US-China Educational Review 7, no. 6 (2010): 1–15.

Fousek, John and To. Lead the Free World: American Nationalism and the Cultural Roots of the Cold War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Fulbright, J. William. “Preface.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 491 (1987): 10 .

Garner, Alice, and Diane Kirby. Academic Ambassadors, Pacific Allies: Australia, America and the Fulbright Program. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018.

Gomez-Escalonilla, Lorenzo Delgado. Westerly Wind: The Fulbright Program in Spain. Madrid: LID Editorial Empresarial, 2009.

Grazia, Victoria. Irresistible Empire: America’s Advance through Twentieth Century Europe. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2006.

Hargreaves, John. On ‘Capillary Power’ See John Hargreaves, Sport, Power and Culture: A Social and Historical Analysis of Popular Sports in Britain. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1986.

Heffernan, Michael, and Heike Jöns. “Research Travel and Disciplinary Identities in the University of Cambridge, 1885-1955.” British Journal for the History of Science 46 (2013): 255–86.

Honkamäkilä, Hanna. “ Interest in Deepening U.S.– Finnish Scientific Co-Operation 1947–1952.” Faravid: Pohlois-Suomen Historiallisen Yhdistyken Vuosikirja 40 (2015): 195–212.

Johnson, Lonnie. “The Fulbright Program and the Philosophy and Geography of US Exchange Programs since World War II.” In Tournes and Scott-Smith, Global Exchanges, 173–87.

Jones, Calvert. “Exploring the Microfoundations of International Community: Toward a Theory of Enlightened Nationaism.” International Studies Quarterly 58 (2014): 682–705.

Jöns, Heike. “‘Brain Circulation’ and Transnational Knowledge Networks.” Global Networks: A Journal of Transnational Affairs 9 (2009): 315–38.

———. “ Centre of Calculation.” In The SAGE Handbook of Geographical Knowledge, edited by John A. Agnew and David N. Livingstone, 158–70. London: Sage, 2011.

Jöns, Heike, Peter Meusburger, and Michael Heffernan, eds. Mobilities of Knowledge. Cham: Springer, 2017.

Kant, Immanuel. “ Idea for a Universal History with a Cosmopolitan Purpose.” In Kant: Political Writings, edited by Hans Reiss. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Koenis, Sjaak, and Janneke Plantenga, eds. Amerika en de sociale wetenschappen in Nederland. Amsterdam, 1986.

König, Thomas. “Das Fulbright in Wien: Wissenschaftspolitik und Sozialwissenschaften am ‘versunkenen Kontinent’.” PhD dissertation, University of Vienna, 2008.

Kramer, Paul. “Is the World Our Campus? International Students and U.S. Global Power in the Long Twentieth Century.” Diplomatic History 33 (2009): 775–806.

Krotz, Ulrich. “Ties That Bind? The Parapublic Underpinnings of Franco-German Relations as Construction of International Value.” Working Paper 02.4, Program for the Study of Germany and Europe, Harvard, 2002.

Latour, Bruno. Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Lebovic, Sam. “From War Junk to Educational Exchange: The World War II Origins of the Fulbright Program and the Foundations of American Cultural Globalism, 1945-1950.” Diplomatic History 37 (2013): 280–312.

———. “The Meaning of Educational Exchange: The Nationalist Exceptionalism of Fulbright’s Liberal Internationalism.” In Brogi, Scott-Smith, and Snyder, The Legacy of J. William Fulbright, 135–53.

Li, Hongshan. U.S.-China Educational Exchange: State, Society, and Intercultural Relations, 1905–1950. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2008.

Lindberg, Leon. “The European Community as a Political System: Notes toward the Construction of a Model.” Journal of Common Market Studies 5 (1967): 344–87.

Loayza, Matt. “A Curative and Creative Force: The Exchange of Persons Program and Eisenhower’s Inter-American Policies, 1953-1961.” Diplomatic History 37 (2013): 946–70.

Mathews-Aydinli, Julie. “ Introduction.” In International Education Exchanges and Intercultural Understanding: Promoting Peace and Global Relations, edited by Julie Mathews-Aydinli. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2017.

Medalis, Christopher. “The Strength of Soft Power: American Cultural Diplomacy and the Fulbright Program during the 1989-1991 Transition Period in Hungary.” International Journal of Higher Education and Democracy 3 (2012): 144–63.

Navarro, Juan José. “Public Foreign Aid and Academic Mobility: The Fulbright Program (1955-1973).” In The Politics of Academic Autonomy in Latin America, edited by Fernanda Beigel. London: Routledge, 2013.

Oelsner, Andrea, and Simon Koschut. “A Framework for the Study of International Friendship.” In Friendship and International Relations, edited by Simon Koschut and Andrea Oelsner, 3–31. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Parmar, Inderjeet. “Challenging Elite Anti-Americanism in the Cold War: American Foundations.” In Kissinger’s Harvard Seminar and the Salzburg Seminar in American Studies, edited by Michael Cox and Inderjeet Parmar. London: Routledge, 2010.

Pietsch, Tamson. Empire of Scholars: Universities, Networks and the British Academic World 1850-1939. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015.

Rupp, Jan C.C. “The Fulbright Program; or, The Surplus Value of Officially Organized Academic Exchange.” Journal of Studies in International Education 3 (1999): 59–82.

Russett, Bruce. Grasping the Democratic Peace: Principles for a Post- Cold War World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Salamone, Frank. The Fulbright Experience in Benin, Studies in Third World Societies 53. Williamsburg, VA: College of William and Mary, 1994.

Schmidt, Oliver. “No Innocents Abroad: The Origins of the Salzburg Seminar and American Studies in Europe.” In Here, There, and Everywhere: U.S. Foreign Policy and the Export of Popular Culture, edited by Reinhold Wagnleitner and Elaine Tyler May. Hanover: New England University Press, 2000.

Scott-Smith, Giles. “The Fulbright Program in the Netherlands: An Example of Science Diplomacy.” In Cold War Science and the Transatlantic Circulation of Knowledge, edited by Jeroen van Dongen, 128–53. Leiden: Brill, 2015.

———. “Mapping the Undefinable: Some Thoughts on the Relevance of Exchange Programs within International Relations Theory.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616 (2008): 173–95.

———. Networks of Empire: The US State Department’s Foreign Leader Program in the Netherlands, Britain and France 1950-1970. Brussels: Peter Lang, 2008.

———. “The Ties That Bind: Dutch-American Relations, US Public Diplomacy and the Promotion of American Studies in the Netherlands since the Second World War.” The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 2 (2007): 283–305.

Singh, Amar Kumar. Indian Students in Britain. London: Asia Publishing House, 1963.

Smith, Richard Candida. Improvised Continent: Pan-Americanism and Cultural Exchange. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017.

Sussman, Leonard. The Culture of Freedom: The Small World of Fulbright Scholars. Lanham MA: Rowman & Littlefield, 1992.

Tournes, Ludovic, and Giles Scott-Smith, eds. Global Exchanges: Scholarships and Transnational Exchanges in the Modern World. New York: Berghahn, 2017.

Tournès, Ludovic, and Giles Scott-Smith. “Introduction: Conceptualizing the History of International Scholarship Programs (19th-21st Centuries).” In Tournès and Scott-Smith, Global Exchanges, 1–30.

Walker, Vivian S., and Sonya Finley ed. “Teaching Public Diplomacy and the Information Instruments of Power in a Complex Media Environment: Maintaining a Competitive Edge.” US Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy, Washington D.C., August 2020.

Wegener, Jens. “Creating an ‘International Mind’? The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Europe 1911-1940.” PhD Dissertation, European University Institute, 2015.

Welch, Antony. “The Peripatetic Professor: The Internationalization of the Academic Profession.” Higher Education 34 (1997): 323–45.

Wilson, Iain. International Exchange Programs and Political Influence: Manufacturing Sympathy? Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2014.

Winks, Robin. “A Tissue of Clichés.” In The Fulbright Experience 1946-1986: Encounters and Transformations, edited by Arthur Power Dudden and Russell Dynes. New Brunswick: Transaction, 1987.

Xu, Guangqiu. “The Ideological and Political Impact of US Fulbrighters on Chinese Students: 1979-1989.” Asian Affairs 26 (1999): 139–57.

Ye, Weili. Seeking Modernity in China’s Name: Chinese Students in the United States, 1900–1927. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001.

Young, Francis. “Educational Exchanges and the National Interest.” ACLS Newsletter 20, no. 2 (1969): 1–18.