Abstract

The main motivation of this paper is to uncover the logic underlying the seemingly inconsistent and erratic foreign policy behavior of countries like Turkey, which are surrounded by different subsystems. The strategic cultures of the surrounding subsystems impose different modes of behavior on borderlands and create attract-repel elements for them. The responses to such elements appear as policies of rapprochement and estrangement, representing closer or cooling relations. Therefore, as part of the attract-repel dynamic, foreign policy behavior appears to oscillate between conflicting extremes. Consequently, the borderland position presents a combination of challenges and opportunities, depending on the comprehensive national power. It can be either reduced to a buffer zone caught between different and imposing entities, or transformed into a hinge state that can change regional or global balances. The underlying logic and ultimate goal of such policy swings, which may appear contradictory and erratic at times, is to become a hinge state in this process by capitalizing on advantages and opportunities, avoiding drawbacks and gaining more power at each step. In this process, Turkey appears as a borderland country that keeps moving between pivotal and linchpin positions, trying to confirm her linchpin status while aspiring to become a hinge state.

There are so many ways to analyze states’ foreign policies, most of which focus on internal factors such as decision-making, leadership, bureaucracy, party politics, ideology, interest groups, public opinion etc., rather than systemic dynamics. This internal focus is a legitimate standpoint because foreign policy is viewed in general as an extension of domestic politics. In that sense, the field of foreign policy analysis appears to be part of political science rather than international relations. The negligence of systemic perspectives is also because of their overly-deterministic and simplistic accounts, as well as not being able to offer a rich set of analytical tools beyond general assumptions of anarchy and the quest for power and security.

Foreign policy analyses from an International Relations perspective require more systemic approaches. The analyses that come closest to such approaches are geopolitical ones, but they focus more on the “geo” than the political, where geography as a fixed reality imposes itself on state policies. They are about the geography of politics. The analyses which place the “political” at the center of their evaluations are found in the literature on critical geopolitics. Although critical geopolitics is about the politics of geography, its focus is still more on domestic politics and the way actors imagine/perceive and spatialize their political visions on their geographies (Tuathail, 1996). The subsystems approach proposed here offers a middle ground between the domestic and system levels.

International political analyses disproportionately focus on great powers and their policies and neglect lesser powers, which can also play crucial roles for international order and security. The middle powers linking different subsystems could be just as consequential as great powers. While such states are under-theorized because of their wide variation in size, power, and political characteristics, their importance in international politics compels us to theorize. The approach adopted here aims to make contributions in understanding non-great powers such as Turkey. The article starts with the general outline of the inter-subsystemic approach, introduces the related terminology, and then moves on to analyze the underlying structure of Turkish foreign policy.

Besides its geopolitical position, the main reason for the growing interest in Turkish foreign policy, especially in the post-Cold War era, is the fact that its behavior as a middle power deviates from the conventional patterns defined by mainstream IR theories. Certain traits and behavioral patterns are attributed to typical middle powers, such as low military spending, seeking to find common ground, interest in international institutions, readiness to assist in conflict resolution (Cox, 1989), status-seeking behavior to distinguish themselves from small powers (de Bhal, 2023), status quo politics and neutrality (Jordaan, 2003, pp. 167, 177), multilateralism, taking compromising positions in disputes, linchpin or bridge roles, economic rationalism, activism, and taking an initiative-oriented approach (Cooper et al., 1993). Middle powers represent a relatively stable middle ground, as the name suggests, both in terms of power ranking and geopolitical position between polarized groups. Despite these generalizations, it is also important to note that there is no typical or homogenous group of middle powers that behave the same way or exhibit invariable characteristics (Holbraad, 1984, pp. 67-81). The policy towards Syria in particular is a striking example of Turkey acting not as a typical middle power but like a great power, perhaps exceeding its power capabilities. For that reason, some call it a “modified middle power” (Altunışık, 2023). Instead of adapting to the policies of one of the great powers in Syria, Turkey formulated its own design facing both the US and Russia at the same time. This paper claims that it is possible to make sense of such behavioral fluctuations through inter-subsystemic dynamics.

While displaying some of the typical features, Turkey deviates from conventional perceptions of rational behavior and acts unexpectedly on occasion. Examples of such perplexing behavior include the signing of a technical and industrial cooperation agreement with the Soviet Union in 1967 at the height of the Cold War; positioning itself against the West in recent years even in economic matters, despite the fact that its foreign trade is mostly with the West (56 percent with Europe vs. 25 percent with Asia); while being an EU candidate country, trying to establish closer ties with or seek possible membership of organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS+; allowing an uncontrolled mass migration in the 2010s by following an “open door” policy as part of Turkey’s sense of historical responsibility; being a NATO member and cooperating with Russia at the same time (nuclear cooperation and the purchase of the Russian S-400 air defense system in 2017 at the cost of being removed from the heavily invested F35 project in 2019); and also clashing with Russia on many issues such as Ukraine and Syria, to name but a few. Despite being a NATO member, Turkey’s reluctance to participate in the sanctions against Russia and its improvement of relations with Moscow during the Ukraine War while simultaneously supplying Ukraine with substantial arms cannot be explained merely by middle power activism or multilateralism. Do these erratic and inconsistent actions then point to some sort of behavioral disorder (Adısönmez & Öztığ, 2024), or to an undiscovered logic that needs to be revealed? Is it possible to come up with a conceptual explanation for such policies beyond leadership choices and personal judgements originating from domestic politics?

As a key country around which all major events revolve, understanding Turkey’s behavioral patterns is of great importance in discovering the overlooked aspects of international politics. Moreover, the shortcomings of the conventional explanations in making sense of Turkish foreign policy have become more apparent in the post-Cold War era. Most puzzling developments, such as Turkey’s estrangement from its Cold War allies and its alignment on opposite sides in the Middle East, are explained with domestic developments, such as the Islamic leanings of the government or the neo-Ottomanist ideology. Nevertheless, this article offers an inter-subsystemic explanation for such unexpected policy shifts.

Contrary to common belief and neorealist assumptions, the international system is not a single whole, but is rather composed of subsystems with their own historical roots, geopolitical assets, and different strategic cultures. Our assessment of the fundamental dynamics of Turkish foreign policy is based on the inter-subsystemic approach (Özdemir, 2015). The model is built on a sort of dialectical logic where differences and contradictions of different subsystems intersect and blend in overlapping areas called “borderlands” and shape state behavior. In general, focusing on these coupling tensions, this model can be used for both global-systemic and country-specific foreign policy analyses. The aim of this article is to provide a framework of analysis for the behavioral dynamics of borderland countries like Turkey.

To summarize our main postulates: (1) the international system does not have a homogenous structure and is divided into different subsystems; (2) each subsystem shapes actor behavior based on its strategic culture; (3) the behavior of the actors situated between different subsystems is shaped by not one but several surrounding strategic cultures and the tensions between them; (4) due to this multiplicity, such actors’ behavioral patterns deviate from others and can seem unpredictable; (5) understanding inter-subsystemic tensions can help us make sense of foreign policy behavior.

The study of international subsystems became popular between the 1960s and the 1980s because of the divisions caused by the Cold War and the emergence of newly independent countries (Brecher, 1963; Kaiser, 1968; Singer, 1969; Haas, 1970; Thompson, 1973; Thompson, 1981). However, at the end of the Cold War, as new theories gained popularity, systemic studies were discredited for their assertive determinism. As a result, subsystem studies could not be developed sufficiently and were limited to studies of different regions. Despite the valuable knowledge produced, these studies did not take the next step towards investigating the interactions between different subsystems. Since actors in each subsystem behave according to a common strategic culture, studying areas of contact between them has great potential to reveal previously overlooked dimensions of world politics.

For that reason, the inter-subsystemic approach, as a belated initiative, intends to take the next step with subsystem studies, which have been largely neglected thus far. Even though the identification of each subsystem and its strategic culture has crucial significance, the ultimate goal has to be studying interactions between these mostly incompatible structures. According to this approach, the most interesting areas that provide important clues about the fundamental dynamics of international politics are the places where subsystems come into contact or intersect with each other, what we call here “borderlands.” Such places provide a fertile ground for research in international politics because the tensions caused by the incompatible and conflicting nature of their strategic cultures merge upon these intersections and shape regional and sometimes global conflicts.

Specifically, what distinguishes a subsystem from others is its strategic culture. In the literature, the term “strategic culture” usually refers to a country’s political perceptions and culture shaping its foreign policy. Here, instead, the term refers to a foreign and security policy shared by a group of states, or an assumed modus operandi, which structures them as a subsystem. Strategic culture provides guidance about acceptable and unacceptable behaviors, the range of policy options, and instruments to be legitimately or successfully deployed that have a better chance of success (Johnston, 1995). Therefore, in each subsystem, what draws the framework of actions and determines the legitimacy or illegitimacy of ends and means is strategic culture. It is the sum total of attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions in settings of threats, opportunities, and settlement strategies (Özdemir, 2008, pp. 16-17). In each subsystem, there is a different and widely accepted mentality shaping the relations, which Buzan (1991, pp. 189-190) calls “a pattern of amity and enmity.” A strategic culture may not necessarily be based on common and shared values, but on the ways competition and conflicts are conducted, and by constraining policy choices and instruments, it allows predictability. In other words, it is a context where both cooperative and conflictual behaviors are shaped (Gray, 1999, p. 50). Hence, the countries with distinct behavioral patterns form a subsystem, which can be identified and defined by its strategic culture.

Therefore, as a fundamental element shaping state behavior, anarchy is not distributed evenly across the international system, neither in kind nor degree, and various forms of anarchy coexist in different regions (Sorensen, 1998; Väyrynen, 1984, Cooper, 2000). For example, in the European subsystem, there is a sort of “mature anarchy” (Buzan, 1991, p. 176) where the absence of a higher authority is mitigated through institutionalization and a sort of legal system under the aegis of the European Union. The current strategic culture of Europe restricts state behavior through its rules and institutions and has significantly eroded state sovereignty, especially (but not exclusively) in economic issues. In such strategic culture, use of force as part of foreign policy is considered strictly illegitimate. On the other hand, the current strategic culture of the Middle East allows actions that better resemble a raw concept of anarchy on which the mainstream IR theories base their assumptions. In such strategic culture, the use of force might be illegal, but it is also commonly resorted to. Cross-border military operations in other sovereign states’ territories are possible depending on the balance of power. Hence, strategic cultures, which define subsystems, are cultures of anarchy shaped by the actors.

The strategic cultures of subsystems and countries mutually construct each other and shape behaviors, standing at the crossroads of domestic and foreign policy. While foreign policy in Europe is mainly based on national interests, in the Middle East it is based on the interests of subnational entities such as ethnic, tribal, or religious groups. This difference has decisive effects on state behavior. While recognizing the crucial importance of domestic factors in foreign policy, this article takes a more systemic perspective to reveal the underlying grand dynamics of foreign policy fluctuations on the bases of inter-subsystemic pressures, opportunities, and risks.

Membership in a subsystem is usually taken for granted and mostly negligible in foreign policy analyses because it does not represent behavioral variation. On the other hand, for a borderland country, subsystemic identification is the most significant variable that causes behavioral variation and sometimes creates strange mixtures of strategic cultures. Stuck between different subsystems and dealing with the tensions of incompatibility, a borderland tries to develop unique behavioral patterns, which do not fit perfectly into any of the surrounding strategic cultures. The tough military actions in Iraq and Syria and harsh statements about the Israeli-Palestinian dispute with its idealistic and humanitarian discourse in Turkish foreign policy is an example of such intermixtures, where European peace rhetoric and Middle Eastern military action are integrated. Given these observations, the inter-subsystemic analysis focuses on two aspects of borderland positions: identity and behavior.

While debates on such positions mainly focus on the matters of belonging and identity, behavioral aspects are largely overlooked. Borderlands, located between different strategic cultures, often struggle to determine how to behave when faced with new developments, sometimes displaying sudden and unexpected changes in behavior. The nature and consequences of such behavioral shifts need to be explored. Between different subsystems, countries facing contradictory modes of behavior try to harmonize these modes as much as possible, dithering between them. If they fail in their harmonization efforts, they might have to choose one over the other. Depending on that choice, they are estranged from one subsystem while they experience rapprochement with the other. This entrapment between conflicting subsystems and the resulting indecisiveness causes foreign policy fluctuations, which, in the end, might be vital for regional and global security architecture depending on the power status of the borderland. The most important reason behind such policy ambivalence originates from efforts made towards finding a middle ground between contradictory demands of the surrounding subsystems. For example, Turkey’s dealings with the Kurdish issue fluctuate between the negotiatory European and military Middle Eastern strategic cultures. After a long military conflict, Turkey followed a solution process (Çözüm Süreci) in 2009-15, negotiated with PKK leader Öcalan, and formed “ a wise-people committee”. Another uncompromising period of armed struggle resumed in 2015 and lasted until the government contacted Öcalan again in December 2024, signaling another shift in style. Our main goal here is to reveal the probable causes of such puzzling behaviors that do not fit conventional policy patterns, on the basis of underlying inter-subsystemic linkages.

Alternative terms exist to define borderlands, such as limitrophe, cusp, or liminal states, which imply being at the edge of a subsystem. These terms also imply that, despite their peripheral location, these actors are primarily part of a region, albeit an idiosyncratic one (Robbins, 2014). “Liminal state,” or liminality, (Yanık, 2011; Rumelili, 2012) also implies a phase of transition from one status to another and ambiguities pertaining identity during this process. Liminal entities are stuck between two domains with no clear identity and are thus accompanied by a feeling of inferiority (Turner, 1966). As an example, Turkey’s westernization efforts, resulting identity issues, and protracted EU membership process point to a liminal status. When stuck in a liminal position, “the deeper and more irreconcilable the contradictions between the two worlds, the more likely that the subject in a liminal position will be fixed there” (Higgott & Nossal, 1997, p. 170). In order to emphasize the fixed, enduring, and unique nature of that position, this paper prefers the term “borderland,” which also evidently has certain liminal features.

While the above terms imply a passage from one side to another, “borderland” refers to an overlapping and more ambiguous zone between two different entities while displaying the characteristics of each, not being a typical member or fully belonging to either one (Özdemir, 2008, p. 33). It is only partially included in the surrounding subsystems, but at the same time, a complete exclusion is not possible for historical and socio-political reasons. As a more neutral term, “borderland” implies neither transition from one side to the other, nor a lack of identity with a transient nature, but is a unique and permanent existence that defies fixed categories. Because of its hybrid nature, it is also most affected by the discrepancies and contradictions of the surrounding subsystems. For a borderland, the dilemmas and fractures created by its geopolitical position are both identity-related and behavioral. The identity-related tension is a result of the uncertainty about whether Turkey belongs to Europe or the Middle East. Behavioral tensions emerge from the incompatibilities between European-imposed modes of behavior, which are more rules-based, institutionalized, negotiatory and multilateral, and Middle Eastern modes of behavior, which are mostly unilateral or bilateral and more power-based. Behavioral fractures are about political/strategic culture, while identity fractures are related to social bonds and culture. Although they are interrelated, the former concerns policy and strategy, while the latter concerns emotional ties.

In this respect, despite all the action around it, a borderland is solitary, and a sense of homelessness dominates its thinking. The main dilemma it faces is choosing between the clarity and security that come with being part of a subsystem and the variety of ambiguous policy alternatives that come with a borderland position. Being part of one subsystem gives a state a sense of security based on predictable patterns of behavior. However, since the binding patterns of a specific strategic culture might be too restrictive for a borderland, it sways between different strategic cultures and vacillates between the safety of solidarity and the freedom of action. This unique position, despite its vagueness and insecurity, comes with flexibility and opportunities, therefore, its historical legacy can be both a blessing and a curse (Cem, 2004, p. 66), depending on power capabilities. In this position, more power means more opportunities, while weakness means becoming a mere buffer zone or an unstable country, such as the Balkan countries (at the end of the Cold War), Ukraine, or Lebanon.

Because borderlands are places between geopolitical tectonic plates (subsystems), their vacillations in both domestic and foreign policy are more radical and erratic, and at the same time, depending on their power, they can have decisive effects in world politics. Borderlands are also the most active and dynamic parts of the international system even during times of relative stability and inertia. During systemic transitions, while other states merely try to adapt to new conditions, borderlands usually experience much deeper and radical transformations, both internally and in terms of systemic identification. For example, the shift in Eastern and Central European borderlands from a socialist to a liberal subsystem (actually, the collapse of the socialist one) in the early 1990s marked the end of the Cold War. Turkey’s shift from Europe to Eurasia and the Middle East in the decades following the 2010s is another example of such radical changes. Such sharp turns in relatively short time periods are particular to borderland countries because of inter-subsystemic dynamics. There are many examples of such radical turns. Turkey signed a free trade agreement with Syria in December 2004 but was arming rebel groups in the Syrian civil war against the government from 2011 onwards; it started membership negotiations with the EU in 2005 but steered away from Europe after 2011. Another example is Erdogan’s decision to host Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi in Ankara in 2024, despite Erdogan’s statement in 2019 that he would never talk to him (Al Jazeera, 2019) and Turkey’s tough stance against him after the 2013 Egyptian military coup.

The borderland position implies a different form of anarchy. While each subsystem has a distinct and established anarchic order that shapes behavior, the borderland, being surrounded by different strategic cultures with its organic (social and political) ties to their subsystems, does not have such a predictable pattern of behavior to which it can adhere. In other words, the common understanding in each subsystem that mitigates the effects of anarchy does not apply to borderlands; this is a state of limbo between different anarchies. There is also an ever-present underlying structure that shapes borderland policies. During the Cold War, the imminent security needs created rigid subsystems based on ideological differences. The ideological caging of the Cold War had restricted inter-subsystemic transactions and made independent strategic action treacherous. When this structure collapsed, incompatible but more flexible and permeable subsystems emerged. Contradictions between them in overlapping gray regions became more prominent, and their effects are felt more acutely in the borderlands. This new transitory period brought new pressures and tensions on one hand, but also created new opportunities and possibilities on the other, especially for strategic autonomy.

While each subsystem provides a certain sense of security to its members, the borderland remains in between and under the impression of constant threat and distrust, the degree of which depends on its power capabilities. Accordingly, it is suspected that the EU is trying to divide Turkey using the Kurdish issue, as well as ideas such as the Middle East being the source of terrorist threats, Russia being the historical enemy, and “the Turks have no friends but themselves.” This is, therefore, the root cause of the securitization that shapes the perceptions and behavior of policy makers. For most countries, this issue is resolved by joining a perceptional and behavioral community (a subsystem or an alliance). But for a borderland country, being a perfectly fitting part of a subsystem is neither possible nor desirable. For that reason, it leans more towards balancing and tries to find security in as much autonomy as possible, where a certain amount of freedom of action can be achieved. In fact, the security policies depend on the country’s power status, where weak states try to find security through compliance with great power policies or joining a subsystem or alliances. Nevertheless, as they become more capable, the search for autonomy becomes more prominent.

From a neo-realist perspective, security can be measured by the extent of autonomy, where an actor is not dependent and can decide its policy goals and means to avoid vulnerabilities. This autonomy also reflects power status (Waltz, 1979, pp. 139-145, 194-195). The great powers in the system have greater autonomy, and the lesser powers adapt their policies to those of the major powers and follow suit. But this dependence is at odds with the borderland identity and becomes more alarming as it gains more power. Cold War experiences particularly shaped the Turkish political mindset in such a way that strategic autonomy became the most important goal (Yeşiltaş & Pirinççi, 2021, pp. 135-137). A striking example of Turkey’s strategic dependence came during the Cuban Missile Crisis, when it became a bargaining chip between the US and the Soviet Union without Turkey’s knowledge or consent. During the Cold War, dependency was more tolerable because autonomous action had more risks than benefits. But then, security dependency became superfluous, burdensome, and even a source of insecurity, as was seen in the US embargo on Turkey in the late 1970s and the problems with the US arms sales to Turkey in the 1990s due to Greek, Armenian, and Kurdish lobbying. As a result, Turkey established the Undersecretariat for Defense Industries (Savunma Sanayii Müsteşarlığı) in 1985 to develop national defense technologies. Such technologies (especially drones), which ended Turkey’s dependence on its allies, gave Turkey the upper hand in its fight against the PKK and changed the regional balance when Turkish technologies were used in regional conflicts such as those in Libya, Syria, Karabagh, and Ukraine (Soyaltin-Colella & Demiryol, 2023).

Strategic autonomy means self-sufficiency and that a country independently decides the ends and means of its foreign policy. Respectively, the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2024) emphasizes its policy being a “national foreign policy.” This emphasis on being “national” reflects a rejection of subordinate roles and is a veiled criticism of the Cold War era, which prioritized the interests of the alliance over national ones. According to such criticisms, Turkey’s ties to other subsystems (Central Asia or the Middle East) remained sub-optimal or shadowed by western interests. Therefore, an independent (national) foreign policy is needed based on freedom of initiative and variety of options in both economic and military matters. It is possible to create such options for borderlands by developing new links with different subsystems. The quest for strategic autonomy is intrinsic to the borderland, within the limits of its power and systemic conditions, because this position requires quick decision-making and sometimes sharp policy turns, whereas binding commitments could slow down rapid policy recalibration. As a result, borderlands might seem like unreliable allies, especially in turbulent times. The indicators of a quest for autonomy can easily be found in political speeches such as that of President Erdoğan (2024):

Contrary to what some people say, there has been no axis shift in our country; rather, after a long search, our country has found its true axis. The name of this axis is “the Axis of Türkiye.” We do not act according to “what others would say,” as was the case in the past. Every decision we take in domestic and foreign policy, every policy we implement is completely based on the concept of the Axis of Türkiye.

In fact, examples of this search for autonomy can be traced back to earlier times. In 1964, when the infamous “Johnson Letter” warned Turkey not to act unilaterally on the Cyprus issue without consulting the United States, and that otherwise Turkey might not be protected against the Soviet threat, Prime Minister İsmet İnönü replied: “A new world will be built, and Turkey will take its place in it.” Indeed, Turkey intervened in Cyprus unilaterally in 1974 to stop the ethnic cleansing attempt against the Turkish minority, followed by a US embargo. This incident shows that even under the conditions of the Cold War, Turkey expected to have a degree of strategic autonomy. Today’s policies towards this search for autonomy are shaped by borderland dynamics, as well as power capabilities.

3.1. Borderland Dynamics

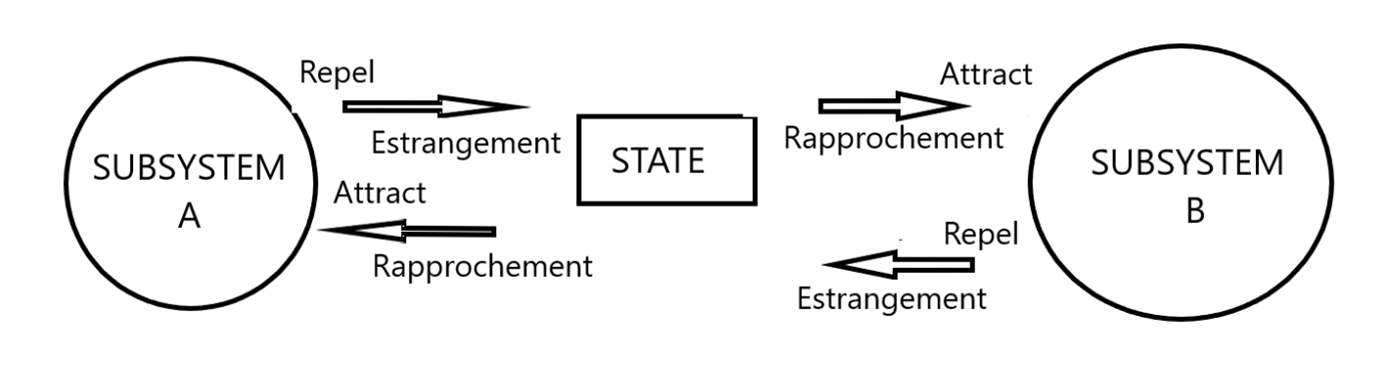

When a borderland is under pressure by surrounding subsystems, it reacts to such strains according to its capabilities, shaping its foreign policy behavior in the process. It is possible to identify two main dynamics and two intervening variables interacting at different levels: “attract-repel” at the subsystemic level and “rapprochement-estrangement” at the actor level. The two key intervening variables are “threat perception” and “power projection contingencies.” While weakening ties, lessening interest, and growing distance refer to “repel” at the subsystem and “estrangement” at the actor level, growing interest and involvement in issues, intensified relationships, and strengthening ties through the gravitational power of a subsystem refer to “attract” at the subsystem and “rapprochement” at the actor level. These two sets of dynamics are mirror images of each other at different levels (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Attract-Repel and Rapprochement-Estrangement Dynamics

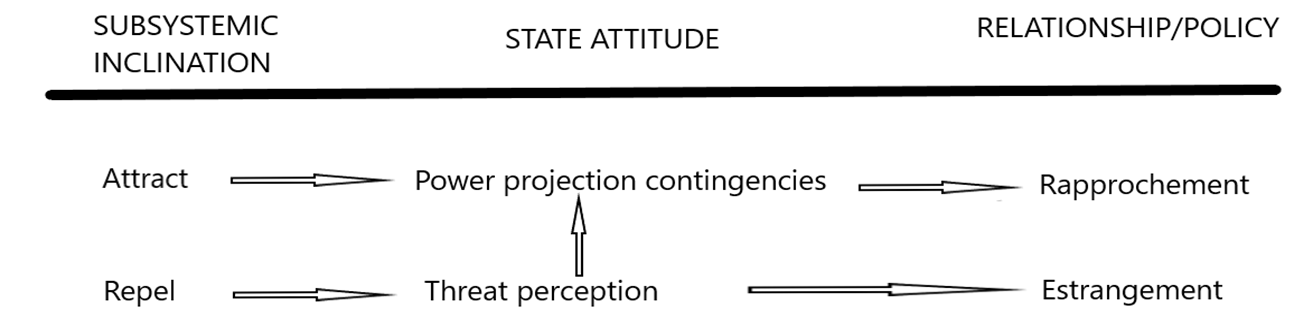

The intervening variables are as follows. “Threat perception” from a subsystem functions as a repel factor and pushes the borderland towards estrangement. “Power projection contingency,” mostly resulting from regional power vacuums, presents possibilities to redesign regional politics to gain advantages (assuming the country has such capabilities). It functions as an attract factor, causing rapprochement, even when such areas of power vacuum produce threat perception. Hence, the main elements determining the degree to which attract-repel dynamics will be converted into rapprochement or estrangement are capabilities, perceptions, and the attitude of the actor.

Normally, repel dynamics and threat perception are interrelated and lead to estrangement. However, in some cases, threat perceptions might be entangled with power projection contingencies and can cause rapprochement (see Figure 2). When the balance between threat perception and power projection contingencies are in favor of the latter, it might cancel out the repel factor and lead to rapprochement, as was the case for Turkey during the Arab Spring. The power vacuum in the Middle Eastern subsystem, especially with the start of the Arab Spring, provided ample opportunities for power projection to reshape regional politics.

Figure 2: Conversion of Attract-Repel Dynamics into Rapprochement or Estrangement

The transformation of Turkey’s relations with Europe is another example of this sophisticated interaction. The western/European subsystem was a security provider for Turkey until roughly the 2010s. Attract dynamics in the west and threat perceptions from the Middle East caused rapprochement with the former and estrangement from the latter. However, the disputes, especially in the Eastern Mediterranean with support from Europe and the US for YPG in Syria, converted an attract factor (security) into a repel factor through threat perception.

The attract and repel dynamics of each system originate from two types of sources: constant and volatile. Constant factors point to the strategic culture. For example, the main attractive elements of the European subsystem are its institutionalization, stability, solid economic base, and predictability. In contrast, the main repelling elements are its restrictiveness and interventions in sovereign rights. While providing a stable and secure environment, it does not allow strategic autonomy and independent decision-making. From this perspective, contrary to the common perception, what made the distance grow between Turkey and Europe after 2010 is not civilizational concerns but has much more to do with a constrictive European strategic culture that limits strategic autonomy. Turkey’s growing inclination to pursue a more proactive policy and take advantage of abundant opportunities in the region at a time of major regional transformations turned these factors into repel elements. For the Middle Eastern subsystem, attract elements include cultural factors, historical ties (the Ottoman heritage), and freedom of action including use of force, while the repel factors are its conflict-ridden nature, insecurity, unpredictability, instability and lack of cooperation. The volatile factors are related to short- and medium-term policy and behaviors. The problems faced in the EU membership process and the rise of Islamophobia and xenophobia are examples of such erratic repel dynamics in Europe. Similarly, if the membership process gains momentum, the attract dynamics might be activated. For the Middle East, the so-called Arab Spring and the consequent Syrian civil war appeared as a volatile attract factor for Turkey.

3.2. Rapprochement-Estrangement Pendulum:

What makes a country a part of a subsystem is its association or socialization with other members of that subsystem and its compliance and alignment with their strategic cultures or behavioral patterns. Since borderlands are marginal members of subsystems, their behavioral patterns and their socialization processes operate differently from others, with rapprochement and further affinity on one end and estrangement and aversion on the other. Foreign policy behavior is mainly shaped by the swings of this pendulum, where the fulcrum of policy falls on the resting point between the gravitational forces of subsystems.

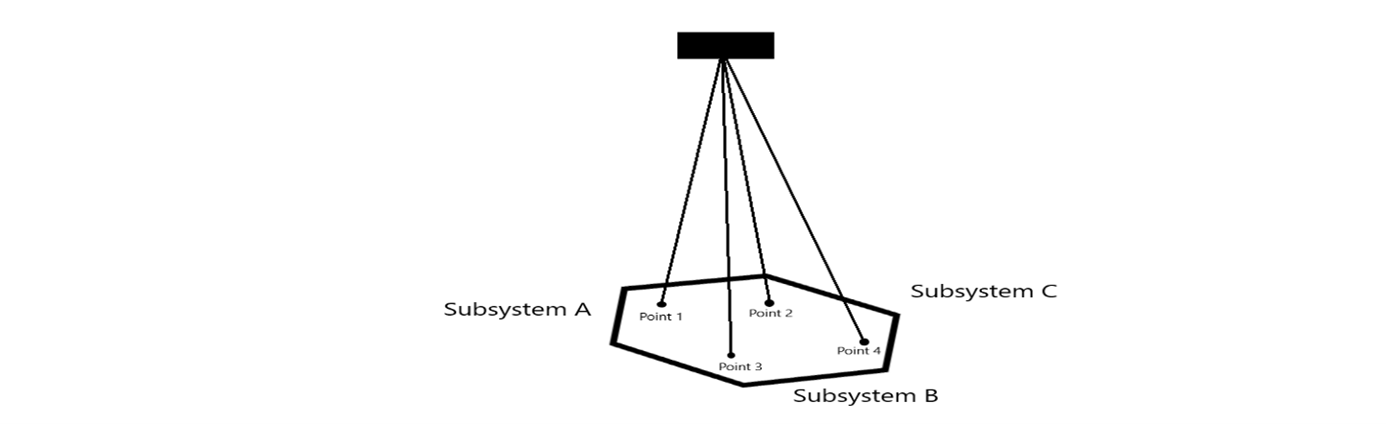

We can think of two different kinds of the rapprochement-estrangement pendulum: one that shows the distance from each subsystem and another that shows the resulting general situation in foreign affairs. The first one shows the current position of the country relative to each subsystem, and the average distance or medium point of balance. This pendulum is multidimensional, where rapprochement-estrangement dynamics are at work simultaneously for each subsystem. It could be visualized something like “Foucault’s pendulum,” where the oscillation area is not perfectly circular but demarcated by the surrounding subsystems. The distance at a certain time from each subsystem is represented as possible swing points in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Foucault’s Pendulum and the Variability of Distance from Subsystems

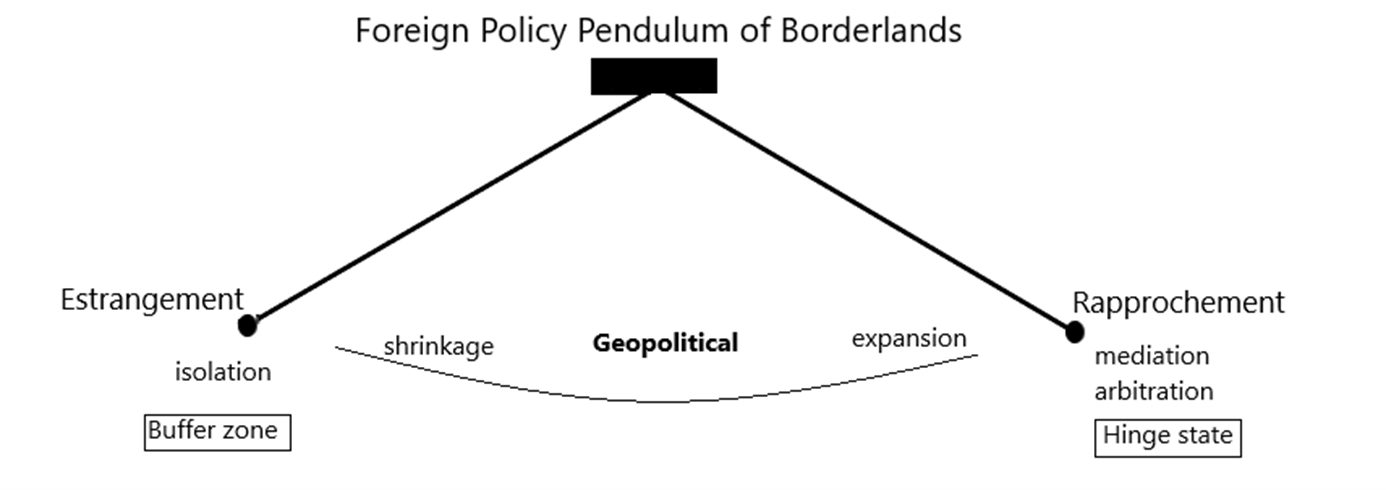

Since it is difficult to visualize the circumstances of “rapprochement-with-all” or “estrangement-from-all” in Figure 3, we need another pendulum to show the general state of affairs. Such a pendulum would depict a dynamic where estrangement from more subsystems causes geopolitical shrinkage and isolation, while rapprochement with more subsystems causes multilateral and vigorous diplomatic activities and expanding geopolitical sphere of influence (Figure 4). That pendulum is a two-dimensional indicator, where “estrangement-from-all” leans more toward being a buffer zone, while “rapprochement-with-all” leads to more central roles. The policy expression of rapprochement-with-all in Turkish foreign policy is “zero problems with neighbors” (Yeşiltaş & Balcı, 2013, pp. 14-15; Zalewski, 2013). Because of their historical and cultural ties with multiple regions, borderlands have more possibilities for rapprochement, and they are in an ideal position for mediation. For example, there is no other country except Turkey that could have mediated between Israel and Palestine, Ukraine and Russia, or Iran and the west. When Turkey had more balanced and constructive relations with Europe, Russia, and the Middle East before 2011, it exhibited a state of multilateral rapprochement, moving in the direction of becoming a hinge state.

Figure 4: General Outcomes of Rapprochement and Estrangement

This general pendulum not only discloses the current political position and the power status of a country in an international system, but also illustrates the general trends in its relations. In order to identify the probabilities for the different forms a state may take on within the range of our pendulum, it is now necessary to discuss specific types of borderlands.

3.3. A Typology of Borderland States

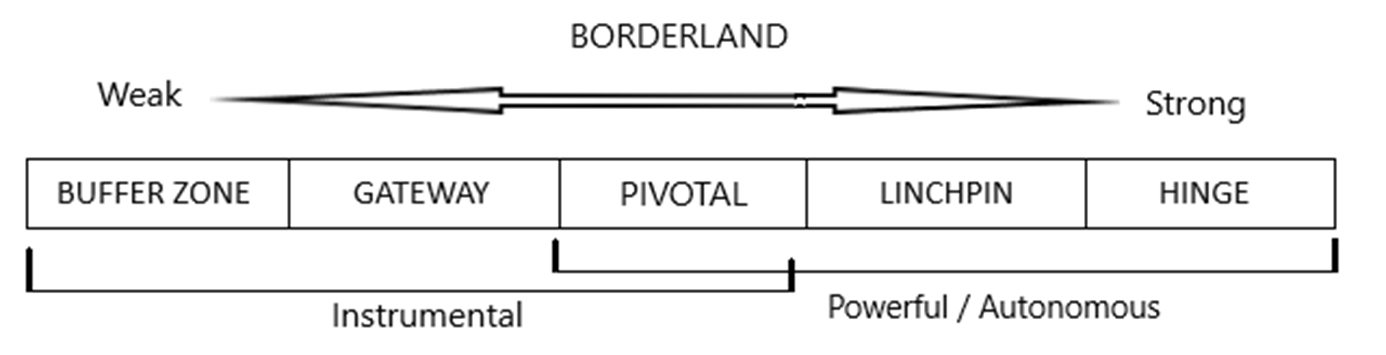

Since states react differently to inter-subsystemic dynamics, they might assume different roles as a result. Here, we take the term “borderland” as a neutral starting point and sort its versions on the basis of their power positions and roles. Geopolitical analyses use various terms to describe such positions interchangeably in a vague manner. However, in this article, each term implies a different role for the borderland state depending on its capabilities. Focusing on behavioral rather than mere geographical dimensions of a borderland, this article takes power capabilities as the yardstick for our conceptual classification. The significance of borderlands in world politics is undeniable, regardless of their power. Buzan (1991, p. 196) also points to the significance of states which “occupy insulating positions between neighboring security complexes.” The first concept related to borderlands as its weakest form is the buffer zone, which separates two regions or subsystems. Buffer zones rarely qualify as actors since they are formed or utilized by other powerful actors for their own purposes to insulate different sides from each other. However, in this paper, insulating the function of a borderland is peculiar to a very specific and exceptional case of weak buffer states. The main and more common function of borderlands is not to insulate, but rather to transmit perceptions, problems, solutions, cultures, views, attitudes, etc.

When a buffer zone gets powerful enough to be considered an actor, it takes on the core functions of a borderland and becomes a “gateway,” which refers to countries at the crossroads of important regions or on major trade routes, migration flows, or cultural intersections (Cohen, 1991). They influence and sometimes control the flow of trade, capital, migration, etc., through their strategic position. Since these countries carry the potential to be a hub of trade, foot traffic, energy pipelines, etc., they are vital for global politics. The term was popularized by Saul Cohen to define regions that are opening gates from one subsystem to another. Unlike buffer zones, the main function of gateways is not insulation but transmission and passage. Another term with a similar connotation is “bridge,” which again implies a weak and auxiliary position. The bridge analogy, due to its passive and instrumental nature, loses its appeal as political and military capabilities improve. Compared to bridges, despite their largely instrumental nature, gateways imply having more control over passages, and their actor quality is more prominent. In that sense, they can also be termed as filter states, which act as both buffers and filtering bridges, controlling passages of migration and other security threats. If the main function is to stop unwanted flows, terms like “bulwark” or “bastion” are also used (Lesser, 1992), with the connotations of a buffer zone.

Another concept that acknowledges the actor qualities of borderlands is “pivotal state,” which, despite its implication of a distinct actor identity, still suggests an instrumentality for other great powers. “Pivot” is a term designated for those taking a central role in a game or a situation, as in the cases when Turkey played pivotal roles in the Cold War against the Soviet Union and when it facilitated western access to the Middle East. However, since the conditions or rules of the game are predefined by more important actors, the pivot role might be changed externally. This was the reason for concerns about Turkey’s declining geopolitical importance (Sayarı, 1992, pp. 11-12; Sayarı, 2000, pp. 171, 180) at the end of the Cold War, which points to the volatility of pivotal roles. What makes a country pivotal is its significance for global strategies and geopolitics, or its relevance for the security interests of great powers (Chase et al., 1996). In the original use of the term, Mackinder (1904) refers to a pivot as a region around which other actors and important events rotate. A pivot state, therefore, is a tenant that occupies that geographical position. Thus, what makes a state a pivot is not what it does, but where it is. In this sense, even though pivotal states assume certain levels of diplomatic clout and economic and military power, they are still relatively passive objects of international politics, or apparatuses of great power politics (Chase et al., 1996). The more recent uses of pivotal states accentuate “regional heavyweights” (Sweijs et al., 2014, p. 8)[1], which can autonomously shape their own security environment by utilizing their power, historical ties, or other regional advantages as active subjects. If the country is geopolitically significant but relatively weak in terms of power, it is a gateway or pivotal state like Ukraine. However, if the country has the capacity to pursue independent policies and even occasionally confront major powers, linchpin or hinge state may be more appropriate terms.

3.4. The Linchpin State, Mild Revisionism, and the Hinge State

The concepts that ascribe greater strategic personality to borderlands are linchpin and hinge states. Linchpin states play crucial roles in regional security, stability, and conflict management as they keep the regional actors together through a web of connections they have constructed. Because of their central roles in regional stability, great powers attach utmost importance to linchpin states. Such states might emerge under two distinct conditions: they can either be at the center of a subsystem as a magnet, holding parts together, or they might emerge as a borderland between two separate subsystems, connecting them to each other and acting as media of communication and facilitators in conflict resolution. While Russia is an example of the first, at the center of the Eurasian subsystem, Turkey arguably might represent the second type linking different subsystems.

Linchpin states are vital for global security, because through their cementing functions, they prevent geopolitical ruptures that could escalate to the global scale. For example, as a NATO member, EU candidate, and also a part of the Middle Eastern subsystem, Turkey plays crucial roles in resolving regional conflicts by connecting different parties and keeping the lines of communication open. The mediation efforts between Israel and Palestine in the early 2000s and between Iran and the US in 2010 are examples of such inter-subsystemic linchpin functions. Again, Turkey’s coordination of a prisoner/spy exchange between Russia and the West at Ankara’s Esenboğa airport in July 2024 (Outzen, 2024), or the Black Sea Grain Initiative with Russia in 2022 to allow Ukrainian grain to reach international markets (Reliefweb, July 27, 2022), are examples of Turkey’s linchpin functions in connecting different groups of countries (subsystems) that have been detached during the war.

Hinge states, on the other hand, garner an even more influential and active position, a sort of central linchpin with more influence. Beyond mediation, more like an arbiter, such states also give angles and direction to all, shaping the relations between the surrounding subsystems. A hinge state cements different subsystems together through conducts of “transformative conflict resolution” practices, diplomacy, cooperation, and perhaps integration. Having close ties (rapprochement) with all actors, it becomes the holder of regional balances, a vital actor for regional and global stability, and has decisive effects on outcomes; and without it, permanent conflict resolution is not possible in either subsystem.[2] Since becoming a hinge state involves a change in power status, transformative influence is inherent in hinge states. As an example, the regime change in Syria in December 2024 was a first in Turkish policy and might be an indicator of becoming a hinge state. Despite all the other great powers in the region, Turkey seemed to determine the final outcome in Syria. When the regime collapsed, Russia and Iran withdrew and the US was left with the YPG on the north-eastern corner of Syria. The management of the subsequent developments and the deals with regional and great powers in the process show to what extent Turkey’s capabilities might lead to becoming a hinge state. Becoming a hinge state as a result of growing and transformative influence also might signal the constitution of a new subsystem centered on the hinge state, depending on the successful management of power relations. A probable coalescence of other actors around the borderland represents its full potential and elevates its status from middle to great power (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Power Positions and Roles of Borderlands

The transition process from a pivotal to a linchpin and finally to a hinge state may be less status-quo-oriented and may lean towards mild revisionism or reformism without disturbing regional stability. Mild revisionism is also a way of achieving strategic autonomy, which is the main prerequisite for becoming a linchpin and a hinge state. Only through such revisionism can the borderland redesign conditions to gain more influence without disturbing stability at both the global and subsystemic levels, as was the case in the Syrian regime change, the calls for UN reform (Erdoğan, 2021), and Turkey’s acquisition of military bases in Libya, Somalia, and Qatar (Banisalamah & Al-Hamadi, 2023). The potential of mild revisionism is inscribed in borderlands and noticeable in every stage, as in the cases of the revision of the Convention Relating to the Regime of the Straits in 1936, Hatay’s accession to Turkey in 1939, and the intervention in Cyprus in 1974. However, it becomes more prominent and assertive as it gets closer to becoming a hinge state. The most striking expression of such mild revisionism can be found in Davutoğlu’s speech (2013a):

In the period of modernity, they tried to make us forget the ancient identities with the newly developed identities, they always tried to fragment us and to narrow our politics, our understanding and our world in constricted moulds. Our understanding of politics today is to close the parenthesis opened in this way and to make a new understanding of politics dominant, first in our country, then in our region, then in the whole world, based on the values of the ancients.

We will render these borders meaningless in the wind of change in the Middle East, together with the governments that will come to power with the will of their own people… The future cannot be built on the Sykes-Picot maps and the subsequent colonial administrations, and then the newly emerging states based on artificially drawn maps and ideologies of nationalism, each blaming the other. We will break the mould made for us by Sykes-Picot… We are in search of a new regional order. A regional order based on … a sense of common destiny.

It should be noted that in becoming a hinge state, a borderland does not cede previous attributes. It still might have a buffer zone, gateway, and pivot and linchpin functions depending on the context, as its strategies require. In the Turkish example, the buffer zone and gateway roles have always been valuable for European and other interests. Even China wants to utilize Turkey’s gateway character to have access to the European markets. The Chinese auto giant BYD signed an agreement with Turkey to open a factory in Manisa to bypass the extra European taxes levied on Chinese automakers (Hoskins, 2024). The pivotal nature of the country has always been an attraction for both the West and Russia. As a linchpin state, it has been an inseparable part of the regional orders and Middle Eastern stability. While the regional actors attach great significance to Turkey as a regional linchpin, Turkey also uses these roles as strategic assets to turn herself into a hinge state and become a global actor.

Actually, all global powers have a hinge state aspect, because just like borderlands, they interact with different subsystems, not because of their geopolitical position but due to the global nature of their power. However, a regional or middle power as a hinge is much more interesting and worth investigating. What distinguishes middle hinges from great ones is not only their power capabilities, but that they are also integral (even if partially) parts of the subsystems they hinge. Great powers are, in most cases, considered outsiders, and their effectiveness heavily depends on regional allies. On the other hand, middle powers are less dependent on great powers to act as regional hinges, as long as they avoid direct confrontations with them.

It is possible to identify up to five or six subsystems surrounding or crossing Turkey, forcing it to act as an axle between them, connecting, balancing, and sometimes coordinating Europe, the Balkans, the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and the Caucasus (Oran, 2001, pp. 25-26), and possibly the Black Sea. However, this paper bases its analyses mainly on three subsystems: Europe, the Middle East, and Eurasia. Irrespective of the identified subsystems, Turkey can clearly be identified as a borderland. Geopolitical fate has placed Turkey between a stable and institutionalized European subsystem (zone of peace) and the most unstable “shatterbelt,” the Middle East. Shatterbelts are regions that are politically and socially fragmented, have contentious state boundaries, and are open to great power interventions from extra-regional actors (Kelly, 1986). As such, they represent the complete opposite of stable zones of peace. Being a borderland between such deeply contradictory environments, which require different modes of behavior and suggest radically different policy instruments, is, in itself, a source of behavioral and identity disorientation, and the main challenge for Turkish foreign policy is to resolve such contradictions. Understanding this challenge would help us make sense of Turkey’s problems with its Cold War allies and its policy fluctuations, sometimes referred to as “axis shifts.”

Turkey’s foreign relations have been heavily influenced by a borderland mindset. Despite its long history, this mindset became especially more prominent after the Cold War. Back in the Ottoman times, though contemporary Turkish geography was not a borderland then, the empire was itself on an intersection of Western, Islamic, and Orthodox spheres. The Balkans especially encompassed a region where all these different allegiances met and sometimes conflicted with each other. Therefore, the borderland psyche is an Ottoman heritage for Turkey. The declining late Ottoman era was characterized by complicated inter-subsystemic balancing games. In that period, the Europeans saw the empire as a buffer zone between themselves and Russia. The Crimean War (1853-56) was an example of the Ottomans balancing an Asian threat with European support. Earlier, when Mehmet Ali Pasha of Egypt, also supported by the French, revolted against the empire and advanced deep into Asia Minor, the threat was averted with Russian support (Hünkar İskelesi or Unkiar Skelessi Agreement) in 1833. On the other hand, after conquering Constantinople in 1453 on behalf of Islam and reaching the height of the empire, Mehmet II used the title “Kayser-i Rum” (Caesar of Rome) for the rest of his life. Such examples suggest that the borderland adopts balancing strategies when weak, but asserts claims over all the surrounding subsystems, and wants to act as a hinge when it is powerful. These are just a few of many examples of the deep-seated borderland mindset that shapes policy makers’ perceptions even today. In order to better understand Turkish foreign policy, we need to comprehend this state of mind. As a reflection of this geopolitical position and the ensuing perceptions, Turkey is viewed as a bridge or a gateway between the eastern and western worlds. But as the power status has improved, discontentment with this role has led to a search for more fitting tasks.

During the Cold War, Turkey identified herself as an integral part of the western subsystem, in terms of both security ties with the US and integration efforts with Europe. Aside from the westernization efforts that attracted Turkey to the western subsystem, the threat perceptions made repel dynamics prevail in other subsystems. However, after the 2010s, when the EU membership process halted and the US policies in the Middle East started posing new threats, Turkey started seeking strategic autonomy outside the west to match its growing economic and military power. For Turkey, the main attractions of the European subsystem are the possibility of EU membership, economic welfare and stability, and reliable security. This prospect also makes Turkey more effective and influential in other surrounding subsystems with its image of being part of a prosperous subsystem (Cem, 2004, pp. 68, 72). Because of this “attract factor,” integration with Europe was the highest goal in Turkish foreign policy until the 2010s, and this led to a predominant rapprochement process. Similarly, relations with the US had their own attract dynamics, such as the military cooperation/aid and technology transfer.

Any problem in these fields turns the same issues into repel dynamics, causing estrangement. For example, the rejection of Turkey’s demand for technology transfer for T-LORAMIDS (Turkish Long-Range Air and Missile Defense System) by the US in 2011 and problems in obtaining US Predator drones were such repel elements which drove Turkey towards self-reliance and alternatives from other technology providers (Rossiter & Cannon, 2022, p. 212), causing estrangement from the western subsystem and rapprochement with others. The main repel dynamics originating from Europe (the west) are ironically linked to the integration process as well. As the integration process has encountered problems, Turkey’s chances of becoming an EU member have significantly diminished, and the threat perceptions of Turkey and Europe started to diverge, as in the case of Turkey’s fight against the PKK/YPG. Because of the European indifference to Turkey’s security concerns, European repel dynamics have been activated. The assumption that the West is in decline in comparison with Asian economies also accompanies the aforementioned as an estrangement factor. A concrete indicator of this estrangement process, as it was worded in The Economist, is that “in 2008 Turkey aligned itself with 88% of the EU’s foreign-policy decisions and declarations. By 2016 that share had fallen by half to 44%. Last year it was only 7%” (The Economist, January 16, 2023). The confrontation in Syria with the US has also intensified estrangement with the west.

Similar dynamics can be identified for other subsystems as well. The magnetism of the Eurasian subsystem for Turkey actually started with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the liberation of the Turkic world. The conversion of this growing interest into an assertive policy did not materialize because of the Russian factor but was later blended with the Asia Anew Initiative (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2019). The main attract dynamics of the Middle East are mostly cultural, but also political, dragging Turkey into regional issues such as the Israeli-Palestinian dispute. Because of the ideological orientation of the political Islamists in Turkey, the Middle Eastern subsystem has an undeniable attractiveness. The region also carries great potential for Turkey to play a leadership role and to design its own strategic goals more freely, compared to the more restrictive European subsystem. Especially after the Cold War, the power vacuum in the region presented Turkey with more power projection contingencies and the role of a regional hegemon. Despite providing opportunities for more autonomous strategies, as a region of interest for other great powers, the Middle East is not free from elements that curtail Turkey’s liberties and pose substantial problems for autonomous action. Any policy towards the Middle East must take the great powers into consideration. The main repel dynamics of the Middle Eastern subsystem are mostly military and threat-related matters, and most of Turkey’s threat perceptions originate from the region. For this reason, although some argue that Turkey should distance itself from the region, historical and religious attract dynamics make Turkey’s complete disengagement or estrangement from the region unrealistic. Therefore, Turkey tries to find an optimal point between rapprochement and estrangement tensions.

An interpretation of these dynamics from the “threat perception” and “power projection contingency” perspective gives us precious insights about foreign policy behavior. In times of weakness, threat perception drives foreign policy approaches towards estrangement. However, in times of strength, the power projection contingency takes precedence over threat perception as the main dynamic. Turkey’s stance towards the Middle East during and soon after the Cold War, when it was relatively weaker, was estrangement due to threat perceptions. In recent years, an emerging power vacuum in the Middle East and Turkey’s achievements, especially in military technologies, have increased the possibilities of power projection, and despite sustained threat perceptions, Turkey is leaning towards rapprochement. In Foreign Ministry circles, Turkey’s responsibility and commitment to solving problems in neighboring regions is expressed in the concept of “regional ownership” (Çavuşoğlu, 2019, p. 56). Davutoğlu (2013, p. 395) also implied the necessity of power projection in this geopolitical position when he said in an interview in 2009, “If we are not assertive in the Middle East, the Middle East will be assertive on us.” As a result, in addition to the occasional ones in Northern Iraq, Turkey had several military operations in Syria between 2015-2020, such as the Euphrates Shield, Olive Branch, Peace Spring, and Spring Shield operations.

The most striking reflection of estrangement before the 2000s is the swamp analogy. According to this analogy, the conflicts in the Middle East were so complex (repel factor) that any rapprochement could lead Turkey to sink in the sludge of these complex problems. During the AKP period, with increasing interest in the Middle East and rapprochement, the swamp discourse was openly criticized by Erdoğan:

calling the region a 'swamp' is ... both racism and a denial of our own origin, essence, and own identity. ... To call a region with which we have cultural, ethnic and religious links a 'swamp' only serves to exacerbate the problems. For our grandfathers a century ago, there was no difference between Medina and Istanbul, or Beirut and Izmir, or Aleppo and Ankara. But our governments turned their backs on this geography, calling it a 'swamp' (NTV, June 17, 2014).

Turkey’s willingness to undertake leadership roles in the region was expressed by Davutoğlu in the following words: “This is the centenary of our exit from the Middle East… whatever we lost between 1911 and 1923, whatever lands we withdrew from, … we shall once again meet our brothers in those lands” (Anadolu Ajansı, 2012). He criticized Turkey’s pivot role in the region as follows:

When Turkey left the region, there was an intellectual-political elite with an Ottoman heritage and an intercommunal geocultural unity that was the product of historical background... Turkey... emphasized its position as a representative of global powers in the Middle East, rather than creating an image of a host country with historical prestige... and alienated from the region (Davutoğlu, 2001, p. 57).

Aside from such regional dynamics, “rapprochement-with-all” is the main route to becoming a hinge state. The “strategic depth” as a conceptual effort to place Turkey in that position implies Turkey’s clout in the surrounding subsystems, using its historical and cultural ties. Other terms such as “order-building actor” or “center state” (Yeşiltaş & Balcı, 2013, pp. 8-9, 15-16)[3] also refer to Turkey’s growing and influential role.

On the other hand, “estrangement-from-all” also happened in 2011-2016. İbrahim Kalın coined this isolation in 2013 as “precious loneliness,” where principled foreign policy is more valuable than rapprochement achieved through surrendering core principles. In the years of “precious loneliness,” Turkey estranged herself from all surrounding subsystems, or in other words, the subsystems had the repel dynamics at work towards Turkey. The estrangement process with Europe had already begun in 2006, when the EU froze eight of the negotiation chapters due to Cyprus-related issues of contention. Especially after the 2016 coup attempt, Turkey’s slide into more authoritarian tendencies further strained relations with the West. The downing of a Russian fighter jet in 2015 also cooled and strained relations with Russia, which caused estrangement from the Eurasian subsystem.

Beginning in 2011, when Turkey became more ambitious to redesign the region (power projection), repel dynamics have been triggered in the Middle East as well due to other regional actors’ reactions. For example, the Syrian policy was one of the major issues causing discontent with Iran and, to a lesser degree, Iraq, while the stance on the Egyptian coup in 2013 and Turkish criticism of the generals who carried out the coup created new tensions between Turkey and the countries which had a different stance on that issue, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Following NATO’s Patriot missile deployments in Turkey, Iran, perceiving this as a threat to itself, forewarned in 2011 that it could launch a missile attack against Turkey if Iranian nuclear facilities were targeted by the US (Hurriyet Daily News, December 11, 2011). Therefore, despite increased interest (rapprochement) in the Middle East, the repel dynamics are strong and active in that period. Within the context of the Eastern Mediterranean gas field contentions, several European and Middle Eastern states (France, Italy, Greece, Cyprus, Israel, Egypt, Jordan, and Palestine) came together to form the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum, excluding Turkey.

Turkey’s new rapprochement initiative with Eurasia in 2016 shows that despite isolation, borderlands rarely run out of alternatives. Closer ties with BRICS+ and a request for membership in 2024, as well as participation in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS+ meetings in 2016 and 2023, respectively, and both at the presidential level, all indicate Turkey’s ongoing rapprochement with the Eurasian subsystem. This was an attempt to alleviate the pressure caused by the repel effects from other subsystems by approaching other subsystems. The existence of these alternatives makes it difficult to maintain the isolation of a powerful borderland like Turkey for an extended period. Consequently, seclusion lasted only five years. Estrangement from other subsystems reveals the rationale behind Turkey’s quest for rapprochement with Eurasia despite conflicting interests in Ukraine in the north and Syria in the south. Russia’s efforts to create new divisions within the western alliance by presenting enticing options for Turkey, such as becoming a hub for Russian gas (Hopkins et al., 2022), appear as an attract dynamic. Despite all its contradictory aspects, we can confidently conclude that as result of subsystemic dynamics, the pendulum hangs near Eurasia at the moment.

As a borderland rises in power status, it becomes more like an acrobat walking on a tightrope or a juggler dealing with multiple and multi-dimensional pressures coming from the surrounding subsystems. While dealing with such tensions, borderlands must also take the global powers’ strategies into consideration. In their foreign policy, “The skills they have utilized are not those of a giant but of a good dancer” (Cooper et al., 1993, p. 24). Examples of such diplomacy include having good relations with Russia as a NATO member and not participating in the NATO embargo on Russia while supporting Ukraine; complying with sanctions against Iran while trading with it; and criticizing Israel and engaging on the Palestinian issue while preserving trade relations. Davutoğlu conceptualized the method towards this goal as rhythmic diplomacy (Yeşiltaş & Balcı, 2013, pp. 12-13), which combines multilateral action and coordination to become an order-instituting country. “No order can be instituted without Turkey. Some order might be instituted, but there is an environment where everybody feels the need for Turkey’s contribution” (Davutoğlu, 2013, p. 421). This sophisticated game of regional design and multidimensional juggling with actors and balances carries a potential of great achievements, but also great blunders. For that reason, for a borderland, the subtleties and quality of diplomacy and the use of skillful diplomats are crucial. Any placement closer to estrangement in our general pendulum (Figure 4) is not a desirable situation in borderland politics because it leads to isolation. The ideal positions are closer to rapprochement for increased regional impact.

As a borderland, Turkey swings the pendulum towards wherever there is an advantage or opportunity in any subsystem. This requires a dynamic and complex set of strategies based on a mixture of opportunism and pragmatism, where inaction is viewed as incompetence. Using the momentum created by these swings, it tries to break out of its subordinate roles and pursue a more autonomous foreign policy, the main parameters of which it determines independently. Turkey’s mystifying rapprochement with BRICS+, a Eurasia-made formation brought together by Russia and China, is also a reflection of this role transformation goal. As Turkey’s latest target, BRICS+, with its patchy membership, brings together countries that have no overriding goal other than to be less dependent and take more central positions in international politics. This is the main reason for the tendency towards mild revisionism and a reflection of Turkey’s desire to become a hinge state. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that any indication of Turkey’s instrumentalization by Russia and China against the West would lead Turkey to rapidly withdraw from this bloc. These quick shifts in position make borderlands inevitable but also unreliable allies (Politico, February 2, 2023), where partnership of such countries is desired but also unsustainable, especially in times of turbulent transition. This unreliability, as a natural outcome of strategic autonomy, has several examples, such as non-compliance with the US sanctions against Iran in 2012-2016, the S-400 deal with Russia, a half-hearted commitment to EU membership, and the termination of strategic partnership with Israel. For the Eurasian partners, support for Ukraine and opposition forces in Syria can be added to the list.

In the situation of rapprochement-with-all, Turkey’s natural role is mediation of regional conflicts because its historical legacy enables its communication with the parties involved in any conflict in the region. This policy of mediation, inspired by the strategy followed during WWII, is coined as “active neutrality,” where the country is involved in all regional problems as a neutral party that actively tries to solve such problems. The key to this policy is to avoid becoming a party to the conflict while increasing regional influence to become a hinge state. If the attract-repel equilibrium is disturbed, Turkey seeks rapprochement with the attracting subsystem. Such situations almost always turn out to be temporary because the very nature of the borderland, with its strong regional ties, prevents the country from being permanently estranged from any one side. During the Cold War, when alliances were based on strict ideological affiliations, the threats from other subsystems (especially from the Soviet Union) pushed Turkey towards the European (western) subsystem. With the end of the Cold War, however, several alternatives have reappeared for Turkey to exploit its ties with other subsystems and its geopolitical position.

Pressed by the inter-subsystemic tensions, Turkey balances threats from each subsystem with opportunities from others. For example, threats from the Middle Eastern subsystems, such as Kurdish separatism, are balanced with the EU membership process, which is seen as a potential solution to the separatist tendencies[4] (Özdemir, 2006). Threats related to the military and technological dependency on NATO have been balanced with closer ties with Russia, culminating in the purchase of the S-400 air defense systems and a nuclear deal where Russia built a nuclear power plant on Turkish soil. Historically, the threats from Russia had been balanced with NATO membership. The energy dependency on Russia is partly balanced by energy cooperation with Middle Eastern countries, which was disrupted by the Syrian civil war. When the relations with NATO and the EU were damaged, Turkey made efforts to improve relations with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS+. All these efforts point to a sort of strategic hedging in which strategic risks and dependencies are minimized by developing alternative orientations and expanding elbow room.

Hedging strategies and the borderland mindset have a great deal of overlap because such strategies are used in situations of uncertainty and complexity, in fluid structures as opposed to rigid or fixed ones, when there is heightened sensitivity to the policies of other actors, and when there are “multiple, sometimes contradictory or competing hierarchies” (Jackson, 2014, pp. 344-346) like the existence of adjacent subsystems. In such situations, countries use a mixture of complex strategies to ensure and protect their vital interests, counterweighing not only the subsystems but also conflicting interests. Towards that end, Kuik (2016, p. 502) identifies the hedging strategy as a third alternative to balancing and bandwagoning, ranging from indirect balancing, dominance denial, economic pragmatism, and binding engagement to limited bandwagoning. All these policies are in line with the borderland mentality of “turning risks into opportunities” (Çavuşoğlu, p. 51) with the aim of achieving a certain degree of strategic autonomy, creating complicated networks and transcending conventional alliances or subsystems. According to Gonzalez-Pujol (2024, p. 197), since the main goal is to gain advantages through avoiding the risks originating from the uncertainties in the system, this strategy inevitably contains certain contradictions. At the same time, these busy networking activities, which, in a sense, stitch together the surrounding subsystems, enable the borderland, rather than being passively caught between them, to steer developments and shape regional conditions, ultimately making it a hinge state. On 18 February 2025, top US and Russian diplomats met in Saudi Arabia to discuss the future of Ukraine, while on the same day, Turkish President Erdoğan met with Zelensky in Ankara and took the initiative to support Ukraine’s territorial integrity at a time when the US had become more willing to compromise with Russia. The international developments during both the Syrian and Ukrainian wars suggest that Turkey is moving towards becoming a hinge state not only between subsystems, but also between global actors such as the US, Russia, and the EU, and between them and regional actors. Throughout these developments, Turkey has demonstrated its willingness to assume regional leadership roles independently, without being overshadowed by global powers.

Given their unique position in international politics, borderlands have crucial implications for foreign policy, and this paper has attempted to unravel the logic behind the policy fluctuations of countries located in such positions through an inter-subsystemic analysis of Turkey. Because of their multiple identities and affiliations, borderlands resist being part of a predefined subsystem, and their foreign policy dynamics differ from other states with clear subsystemic identities. Former Foreign Minister İsmail Cem (2005, p. 68) argues that Turkey’s geopolitical position gives it the opportunity to utilize its power at the maximum as long as it is not artificially compelled to choose between the surrounding alternatives. In uncovering borderland dynamics, the article first looked at the borderland mindset to discover the behavioral logic behind foreign policy, because behind seemingly contradictory and impulsive policies lies a kind of borderland thinking. Their geopolitical position, while causing both behavioral and identity confusion, also presents ample opportunities and options for foreign policy. Such opportunities also provoke a desire for more power. Such a position creates vulnerabilities when these countries are weak but offers a wide range of alternatives and opportunities as they get stronger.

In order to achieve both power and security, a borderland tries to take advantage of inter-subsystemic dynamics (attract-repel) and follows rapprochement-estrangement policies. This is the main underlying dynamic that shapes foreign policy behavior. Each swing in the pendulum is readjusted to take advantage of the benefits and minimize the drawbacks. As a member of NATO, Turkey’s rapprochement with the Eurasian subsystem can make more sense in the context of such dynamics. The long-term strategic roadmap, which follows complex paths shaped by estrangement-rapprochement moves, is ordered in two stages: (1) gaining strategic autonomy to be able to freely exploit inter-subsystemic dynamics, and (2) move up in the power hierarchy of international politics. The first step in eliminating the inconveniences of the borderland position is to achieve freedom of action, or strategic autonomy, which is a logical prerequisite for playing the linchpin and hinge roles. Only such powerful roles can mitigate the tensions and contradictions of surrounding subsystems. The second stage comes as an outcome of the accumulative gains in the oscillation process. This entire process, seemingly involving contradictory, irrational, and trivial policies resulting from domestic politics and personal preferences, is actually both a part and an outcome of an imposed logic deeply rooted in inter-subsystemic tensions.

Both stages of this strategic roadmap involve mild revisionism, requiring prudent handling of sophisticated networks. Such revisionism is the way out of the discomforting dilemmas of borderlands, reorganizing the regional orders to position themselves at the center as a hinge. In that process, the greatest risks are related to premature role undertakings, where policy goals exceed power capabilities. The move towards becoming a hinge state comes with greater confidence, which might be perilous if it leads to policies that exceed capabilities and overlook the inter-subsystemic and great power interactions. Such variables and the timing of new role undertakings represent a thin line between success and failure. For example, the Syrian policy seemed like a wrongly timed initiative where Turkey tried to play a hinge state role while its capabilities were at the linchpin level. However, the inter-subsystemic web of interactions caused the fall of Assad, and Turkey appeared as the sole victor to beat Russia, the US, and Iran simultaneously. Based on the analyses here, Turkey appears as a borderland country that keeps moving between pivotal and linchpin positions, trying to confirm her linchpin status while aspiring to become a hinge state.

The timing of seizing opportunities under multivariate conditions is one of the main challenges facing borderlands as they seek to move up the power hierarchy. The main challenge that borderlands face at every stage of their attempt to become an independent actor is that the global powers always view them as auxiliary. Turkey’s NATO allies have always regarded it as a pivotal state, while the US’s Greater Middle East project has recognized its linchpin status. However, the failure of this project and Turkish ambitions to go beyond supportive roles in shaping regional politics confused its Western allies and made it difficult for them to accept the new status that Turkey yearned to achieve. Thus, “status recognition” emerges as a cornerstone defining foreign policy concerns of borderlands in their journey up the power ladder. A logical consequence of this ascension to hinge state status is that at some point, they seek to supersede great powers in their region and thus might have occasional disputes with them.