Abstract

How do we conceptualize compartmentalization as a foreign policy behavior? This paper will argue that compartmentalization is a practical and cognitive approach to foreign policy decision-making and behavior at times of contradictory pressures arising from domestic or external realities, when actors need to make stark choices between different alternatives. Having delineated the boundaries of this concept, the article will engage in an extensive review of the literature employing the concept of compartmentalization in the study of Turkish foreign policy. It will trace how Turkish foreign policy conduct increasingly adopted this behavior in at least two distinct forms: issue-based and actor-based. The paper will argue that the widening scope of this practical-cognitive behavior is a result of a number of systemic and domestic-state level factors, which are closely related to the evolution of Türkiye’s domestic realities and international positioning against the background of a changing international system. Moreover, the paper will argue that at the individual-ideational level as well, compartmentalization has been part of a set of cognitive priors which affect the Turkish foreign policy makers’ formulation of alternative foreign policy strategies.

1. Introduction

Globalization has deepened complexity in international politics by diffusing power, multiplying the number of actors, and creating interdependencies among actors across various issue areas and regions. While states pursue multiple agendas, external and domestic issues have become increasingly entangled. The widening complexity in international politics has given way to puzzling patterns and forms of bilateral relations among states, diverging from the conventional and holistic understanding of amity, enmity, or neutrality (Aydinli & Rosenau, 2005). A particularist and compartmentalized approach to foreign relations is also gaining ground, whereby states work with other counterparts in various issue-areas or loci in order to realize mutual gains and mitigate shared concerns. There has been no shortage of scholarly attention to decipher those apparently contradictory foreign policy behaviors by states in this complex, globalized yet transitioning world system.

We study here compartmentalization as a ‘form of foreign policy behavior practiced by states’ and a ‘cognitive prior adopted by leaders’ (Acharya, 2009) to cope with challenges arising from complex interactions in contemporary world affairs. We will argue that compartmentalization essentially involves a practical-cognitive approach to foreign policy decision-making at times of contradictory pressures arising from competing or mutually exclusive alternative sets of relationships or choices at either domestic or external levels. Such usually high-stake decision-points are more likely to arise during times of systemic polarity, intense strategic rivalry, systemic transitions, or in the case of multifaceted relations, wherein interest divergence in some areas goes hand-in-hand with shared interests in other areas which are worth not foregoing. At such junctures, compartmentalization emerges as one of the alternative avenues to make cooperation possible, by allowing the parties to ‘agree to disagree,’ as the popular saying goes.

Although compartmentalization has been used in the literature for quite some time to describe contradictory positions and complex relations between various states, there is no systematic analysis of this concept, nor has there been a well-established operational definition instructing such analyses. Most uses of ‘compartmentalization’ are idiosyncratic, as scholars employ the term in a casual sense. The purpose of this article is to develop a comprehensive framework which can be used for foreign policy analysis, by conceptualizing compartmentalization as a foreign policy behavior at practical and cognitive levels. What follows is an attempt to define compartmentalization, by suggesting a typology of different forms of this behavior and its main components. This section will also delineate the concept further to differentiate it from other similar concepts used in foreign policy analysis, particularly transactionalism and hedging. Then the article will engage in an extensive review of the literature employing the concept of compartmentalization in the study of Turkish foreign policy. In addition to tracing the evolution of how this concept has been applied, this section will overview various manifestations of issue-based and actor-based compartmentalization. Rather than engaging in a detailed case study analysis to test the applicability of the compartmentalization hypothesis, the purpose of this inquiry will be to provide an illustrative survey of how Türkiye’s relationship with several countries, such as Russia, Iran, Israel or the United States, had elements of compartmentalization. Next, the discussion on the drivers of compartmentalization in Turkish foreign policy conduct will also highlight how it has emerged as a cognitive prior, shaping the leaders’ approach to foreign policy. The concluding section will revisit the role of compartmentalization as a strategic-cognitive process in Turkish foreign policy of late, referring to the pressures exerted by the securitization of the regional environment.

2. What is Compartmentalization? Delineating the Boundaries

How do we conceptualize compartmentalization as a foreign policy behavior? Compartmentalization may refer to a number of interrelated phenomena. Traditionally, compartmentalization in foreign policy studies referred to the division of power and labor among various bureaucratic institutions (Clifford, 1990; Mueller, 2013; Delreux & Earsom, 2024). This practice is mainly justified on rationalist grounds, as decision-makers are often assumed to separate different issues from each other at cognitive and practical levels to manage simultaneous and complex challenges. As Smyth notes (Smyth, 2021, pp. 414-415) it refers to “the way in which decision-making processes organize themselves to isolate specific issues for consideration within discrete compartments” that “fit well with economic rationalist perspectives on human action that see people as rational actors seeking to maximize their utility in any given situation.”

The concept is also used to refer to the insulation of domestic politics from foreign policy, the delinking of economic and trade policies from diplomatic and security relations, or the detachment of a specific foreign policy issue from other disputes. In a related sense, different issue domains can be delineated as “compartments,” which are usually driven by distinctive focus, logics or dynamics (Choiruzzad, 2017, p. 46). In this respect, a typical example for compartmentalization is the isolation, at the height of the Cold War, of nuclear risks from the entire set of problems in relations between the two superpowers, which agreed on a compromise in that issue area. Likewise, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) of July 2015 could be viewed as a textbook example of compartmentalization, in which the concerned parties, namely Iran and the United States, successfully insulated the nuclear issue from other questions and reached a compromise (Akbarzadeh, 2024). Recently, there were references to this concept in the Biden administration’s approach to the relations with China in the context of climate change.[1]

Compartmentalization is also increasingly used as an analytical tool to explain contradictions and apparent inconsistencies in state behavior. Several recent studies employed the concept of compartmentalization as an explanatory framework to understand puzzling foreign relations of various countries, especially in their bilateral relations with certain counterparts (Délano, 2009; Patrick & Bennet, 2014; Cornell, 2016; Kang & Kim, 2017; Kundnani & Puglierin, 2018; Rudd, 2022; Brugier, 2022; Tsintsadze-Maas, 2024). In that genre, the concept has been employed in the analyses of Turkish foreign policy, particularly in its relations with Russia and Iran, as will be reviewed below. Before moving to the Turkish case, this section will seek to delineate the analytical boundaries of the concept.

2.1. Issue-based vs. Actor-based Conceptualization

Compartmentalization can be divided into two broad categories. Firstly, compartmentalization can have an issue-based meaning in the sense that it refers to the separation of policy domains from one another in a relationship with a single actor. In that respect, states may resort to this instrument to maintain cooperative forces against the backdrop of conflictual dynamics. It thus, for instance, offers a balance between long-term security and short-term economic interests. Secondly, compartmentalization also has an actor-based meaning, whereby it implies the tendency to conduct relations with one actor in isolation from others. States may use this instrument in pursuit of mutually exclusive partnerships, i.e., with two or more rival actors or blocs. Thus, for instance, it may particularly help states balance off treaty-based and long-established alliance dynamics with the ad hoc or emerging relationships with non-allies.

In a related sense, the concept may also be used to refer to the role of the leaders at the domestic-external nexus. Considering the contradictory expectations by the domestic and international audiences, leaders often confront challenges in decision making. Compartmentalization can be a tool to reconcile the tensions arising from differences in the domestic agenda and foreign policy priorities.

2.2. Compartmentalization at Cognitive and Practical Levels

Compartmentalization operates at two distinct but interrelated levels: cognitive and practical. Firstly, it functions as a cognitive process on the part of decision-makers, who may employ it to manage contradictory pressures for cooperation and contention arising from various sources. Relying on their previously held ideas, perspectives, worldviews or rational calculations, decision-makers may adopt compartmentalization at a cognitive level, as they decide with whom (actor-based compartmentalization) or on which issues (issue-based compartmentalization) they will cooperate. Secondly, at the practical level, compartmentalization can be conceived as a foreign policy behavior, whereby policy makers take actions such as detaching the country’s bilateral relations with various actors from each other (actor-based compartmentalization), or forging cooperative frameworks in order to handle complex, multifaceted and otherwise conflictual relations with certain counterparts (issue-based compartmentalization).

Here, Acharya’s (2012, p. 193) conceptualization of “cognitive priors” as “the preexisting ideas … of individuals or societies -whether they are worldviews, causal ideas, or principled ideas” can help us better understand the cognitive dimension of compartmentalization. Actors could bring various preexisting beliefs, ideas or schemas to new situations as they respond to them. There is a wealth of political-psychology scholarship looking at how those cognitive priors are informed or how individuals -leaders- organize the world in their mind. These are beyond this article’s focus, and for our purposes here, what matters is whether cognitive factors matter causally. At this point, while it is also beyond the scope of this study to analyze the role of ideas in international relations, it is helpful to recall Goldstein and Keohane’s (1993, p. 12) contention that ideas have the potential to influence policy outcomes through various causal pathways. They could serve as roadmaps, affect strategic interactions, or become embedded in institutions. In that respect, compartmentalization can also be viewed as part of the cognitive priors that leaders bring with them, which eventually affect the way they process information, respond to strategic environment, and eventually make foreign policy decisions. Thus, compartmentalization emerges as a result of a cognitive-strategic process, whereby the ideas shared by the elites and the policy practices -material factors- mutually interact.

2.3. Compartmentalization as a Form of Cooperation: Linking vs. Delinking Multiple Issues

Compartmentalization can best be conceptualized as a form of cooperation, which is a product of strategic interactions where actors’ deliberate policy choices determine the outcome. This phenomenon challenges a zero-sum approach to international relations, as it is driven by states’ search for reaping mutually rewarding opportunities. When actors cannot afford abandoning dividends of cooperation on certain areas, or cannot remain indifferent to looming risks or opportunities, they tend to conduct their relations with different states on separate tracks, or isolate issues of conflict and divergence from the areas of potential cooperation in bilateral relations, with an aim to minimize potentially adverse effects of the disagreements on the overall foreign relations. Moreover, a major factor highlighted by the cooperation literature is obviously at play here: shadow of future. As Milner (1992, p. 474) argues, actors’ “willingness to cooperate is influenced by whether they believe they will continue to interact indefinitely,” which is directly related to their assessment about the stability and the future of their environment. In any case, achieving this outcome requires an important degree of coordination between the parties, which is largely discussed by the neo-liberal scholars of cooperation during the 1970s and 1980s (Axelrod & Keohane, 1985).

Seen from this perspective, compartmentalization emerges as an outcome of a rational choice on the part of decision-makers to delink different issues and domains that arguably have different structures and dynamics, which affect the prospect of cooperation and competition. Depending on the nature and content of the isolated issue domains or problems, decision-makers coordinate and adjust state policies with their counterparts and relevant stakeholders “if they wish to gain various benefits of cooperating” (Fearon, 1998, p. 271). Again, as states seek to reduce negative implications of competition and rivalry in one domain into other ones (Milner, 1992, p. 467), compartmentalization as a way of separating issue domains from each other emerges as a suitable instrument.

Therefore, compartmentalization appears to enjoy an interesting relationship with one of the essential mechanisms of international relations: issue-linkages. As underlined by neo-liberalism, the growing interdependence among countries in terms of economy, trade, security as well as deepening social and cultural interactions have created multiple channels to increase possibilities of cooperation, which in turn creates opportunities for the states to use linkage-politics to expand their benefits from cooperation (Keohane & Nye, 2012) or promote peace and stability.

While linkage politics refers to actors’ ability to manipulate the connection and interdependence across issues, the logic of compartmentalization hinges on the ability to isolate or decouple issues from each other so that conducting them on separate platforms becomes possible. The neo-liberal theses on ‘interdependence’ or ‘trade promotes peace’ all assume that there will be positive externalities and spill-over from areas of cooperation in low key issues, which will eventually come to encompass high politics issues, creating conditions for peace and stability. In the case of compartmentalization, however, the logic is different. The ‘disconnect’ or ‘delinking’, i.e., the containment of issues or domains of conflict and cooperation and the prevention of spill-overs from the political arena to economic sectors, is rather what makes cooperation possible, as it potentially helps maintain a conditional and minimum peace and stability between nations.

2.4. Cross-cutting Realist vs. Liberal Rationality: Relationship to Other Strategies and Approaches

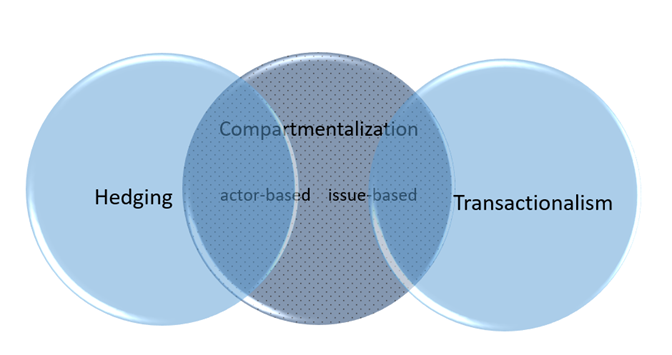

Overall, in states’ foreign policy toolkit, compartmentalization refers to a pragmatic behavior and a mode of relationship, confined to specific issue areas, domains or actors. Compartmentalization incorporates elements of return-maximization (liberal) vs. risk-contingency (realist) behavior, thus catering to several motivations ranging from conflict management, utilitarianism, strategic flexibility, or signaling of intentions. Compartmentalization as a practical/cognitive behavior is a specific tool that must be considered against others, as well as in careful consideration of its benefits versus costs. In many ways, it resembles and partly overlaps with two popular concepts, namely hedging and transactionalism, but it is also distinct from them (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Compartmentalization in relation to other similar concepts

On the one hand, as a foreign policy behavior, compartmentalization resembles transactionalism, which rejects a holistic approach to foreign policy making, and tends to conduct foreign relations based on pragmatic, short-term and reciprocal exchanges, mostly devoid of a normative content and long-term shared strategic perspective (Kardaş & Ünlühisarcıklı, 2021, p. 7). Transactionalism may as well overlap with compartmentalization in the sense that relations with partners can be handled in distinct and narrowly defined compartments governed by separate logics based on short-term considerations, rather than one single shared strategic vision or logic of long-term cooperation shaping all issue domains. However, transactionalism also differs from compartmentalization in significant ways. For one, whereas transactionalism is usually the mode of interaction between two actors based on short-term calculations and zero-sum logic, paradoxically long-term considerations are built into compartmentalization as well. In a compartmentalized bilateral relationship, a transactional mode of relationship characterized by calculation of short-term gains in one issue area may co-exist with a long-term strategic vision in other issue domains. Indeed, it is the ‘shadow of future,’ i.e., the concern to sustain long-term shared interests, that incentivizes cooperation. In other words, a compartmentalized relationship between two states sharing immediate historico-spatial environment may be characterized by multiple dimensions of evolving strategic interactions, achieved through the isolation of issues of divergence which may or not be managed on the basis of transactionalism. Moreover, since transactionalism mainly refers to how relations are managed at a bilateral level, it overlaps mainly with the issue-based understanding of compartmentalization only, but not necessarily with the actor-based meaning of compartmentalization.

On the other hand, compartmentalization has also a close relationship with hedging, which seeks to cultivate close relations simultaneously with a number of competing actors with the aim of lessening risks and maximizing gains, i.e., ‘return maximizing’ and ‘risk contingency’ policies (Pujol, 2024; Zha, 2022; Kang & Kim, 2017). Actor-based compartmentalization provides flexibility to maintain multi-vectoral policies, by simultaneously developing economic, diplomatic and security engagements with various and competing actors. As much as it resembles hedging strategy, compartmentalization cannot be reduced to this concept. For one, we treat compartmentalization not as a foreign policy strategy but a practical/ cognitive behavior, which can be employed in conjunction with other strategies. Although compartmentalization aligns largely with hedging strategy, states may employ it as part of other foreign policy strategies, most notably balancing or bandwagoning. Actor-based compartmentalization could be regarded as a substantial element of hedging strategies that states employ when they are forced to choose between two or more alignment options in high-risk situations. Nonetheless, compartmentalization can manifest itself both in terms of choice between two actors and in relations with a single actor, since the logic of issue-based compartmentalization also entails separation of issue domains in bilateral relations of any two states. Moreover, hedging concept is usually employed to study the behavior of small states vis-à-vis great powers (Kuik & Rozman, 2015), but compartmentalization can be a practice exercised by any size of state. Likewise, while hedging is usually related to high stakes choices between competing powers in situations of uncertainty, these conditions are not always necessary for compartmentalization.

3. Compartmentalization in Turkish Foreign Policy

There is a tendency in the recent scholarship on Turkish foreign policy to define certain dimensions of Türkiye’s international relations or the nature of its bilateral relationship with certain countries as ‘compartmentalized.’ In policy analyses as well, it has been increasingly emphasized how, despite the prevalence of political disagreements and geopolitical rivalry, Türkiye has arguably pursued a ‘positive agenda’ and effectively employed compartmentalization in its dealings with a number of neighboring countries, regional powers, and great powers (Özkan Erbay, 2021). However, as stated earlier, there is no systematic analysis of this concept, nor is there a well-established operational definition instructing such analyses. Most uses of compartmentalization are idiosyncratic to the particular authors, who rather draw on the casual meaning of the term without offering a uniform definition on the content and implications of the concept.

3.1. Types of Compartmentalization

There are at least two different usages of the concept in the literature with regards to Turkish foreign policy. Firstly, the widest use of the term compartmentalization takes an issue-based approach to the concept. It has been employed to describe the nature of Türkiye’s multi-dimensional relations with single countries, most commonly with the two regional rivals, namely Russia and Iran, as will be reviewed below. These scholars identified a pattern whereby this dynamic was in play not only across issues but also even within a single issue-area. Thus, there is a growing number of studies which highlight how a cooperative relationship in the economic realm evolved in parallel with adversarial relations in the political-strategic realm, in the case of both Iran and Russia.

Secondly, in earlier studies it is also possible to trace the use of compartmentalization in an actor-based sense, referring to Turkey’s relations with different countries or regions. In older accounts of Turkish foreign policy toward the Middle East, some experts argued how one of the fundamentals was a concern to conduct Turkish policy in the region in isolation from its place within the Western alliance system, as well as maintaining a balanced relationship with both Israel and the Arabs (Kamel, 1975; Taşhan, 1985, pp. 9-11). While Robins (1992, p. 85) characterized it as ‘separate’ and Hale (1992, p. 681) as ‘detached’, later Mufti (2002, p. 82) termed this attitude as compartmentalization. Aybet (2006, p. 541) also noted how Türkiye’s ‘successful’ separation of its Middle Eastern relations “from East-West relations and regional confrontations … was a practical way of dealing with the delicate and ever-changing political map of the Middle East, as well as Turkey’s policy as a NATO country within the region.” [2] In the post-Cold War era, the scholarship on Turkish foreign policy widely underlined a pattern whereby the country’s multidimensional ties with neighboring actors, particularly Russia, Iran or China, evolved despite the objections coming from the United States, which also coincided with greater incidence of compartmentalization.

3.2. Cases of Compartmentalization in Recent Turkish Foreign Policy Practice

In recent decades, compartmentalization has become a widely applied practical tool in Türkiye’s external conduct. While issue-based compartmentalization helped Türkiye maintain complex relations with certain states despite divergent positions, actor-based compartmentalization has facilitated the development of simultaneously good relations with apparently adversarial powers.

The widest application of the concept has been in the context of Turkish-Russian relations (Öniş & Yılmaz, 2016; Erşen, 2017; Frappi, 2018; Demiryol, 2018; Kardaş, 2019; Rüma & Çelikpala, 2019; Hamilton & Mikulska, 2021; Köremezli, 2021; Balta & Bal, 2025). In many ways this case has been treated as a textbook example of issue-based compartmentalization, whereby many experts have depicted the nature of Türkiye’s conduct with Russia as a “strategic process of isolating economic cooperation from broader geopolitical conflicts” (Cornell, 2016). While some tended to call it an emerging ‘compartmentalized alliance’ (Giannotta, 2022) others traced it to the signing of the Joint Action Plan for Cooperation in Eurasia between Türkiye and Russia in 2001, which also involved mutual respect of each other’s spheres of influence and a commitment not to undermine each other (Köstem, 2017, pp. 6-7).

Compartmentalization in Turkish-Russian relations could also be observed even within a single issue-area, including such strategic sectors as energy or defense cooperation. For instance, while Ankara has been in direct competition with Moscow in the Western-backed Southern Corridor through Nabucco or TANAP, it also has pursued energy partnerships with Moscow through joint pipeline projects, namely Blue Stream or Turkish Stream, not to mention Russia’s role as a major natural gas supplier or contractor of the first nuclear power plant (Kardaş, 2012). Likewise, in the military field, despite cooperation in arms procurement as in the case of the S400 purchase, the two sides confronted each other directly in Libya and Syria, and indirectly in the Southern Caucasus (Coffey & Kasapoglu, 2023).

Dynamics of actor-based compartmentalization have also been manifested in various dimensions of the Turkish-Russian relationship, since Ankara has cultivated and deepened cooperation with Moscow on economic, energy, and commercial issues, despite its alliance with the United States. Interestingly, issue-based and actor-based compartmentalization have reinforced each other. As Kardaş (2019, pp. 2-3) notes, the compartmentalization of relations with Russia not only enabled the two countries to “agree to disagree, focusing on areas of convergence and allowing, yet also containing, divergence in other issue areas”, but to the extent it “allowed for a differentiated relationship with degrees of divergence with Russia,” this practice also helped to manage the tensions with the Western partners, and defuse their criticism.

While some analysts underlined the fragility of compartmentalization in the face of the Russian-Turkish crises, and even some argued that it completed its life course especially after the downing of a Russian fighter jet in Syria in late 2015 (Cagaptay, 2016),[3] the two parties managed to move beyond this phase, underscoring the durability of this strategy. In a ‘successful’ showcase of such compartmentalization in subsequent years (Ozkarasahin, 2022), Türkiye has proven able to maintain good ties with both belligerents, by pursuing active neutrality during the Russia-Ukraine war. In the same line, despite their divergent positions on the fate of the Assad regime and the Syrian opposition, Türkiye has managed to preserve its shared interests and disagreements with both Iran and Russia, which culminated in the trilateral dialogue in the Astana format on the management of conflict in Syria.

The Turkish-Iranian relationship is also another case widely discussed as an example of compartmentalization (Sinkaya, 2014; Kırdemir, 2014; Sinkaya, 2016; Cagaptay, 2016). As regards issue-based compartmentalization, historically, Türkiye and Iran have preserved a fine line between friendship and rivalry amid the simultaneous but competing dynamics that oscillate between cooperative and conflictual trends (Sinkaya, 2019). Thus, despite their diverging positions and strategic priorities on many regional files ranging from Syria to the South Caucasus, both states have maintained political dialogue and economic cooperation. Likewise, patterns of actor-based compartmentalization have remained always present. Against the background of Iran’s problematic position within the international community, Ankara has conducted its relations with Tehran on its own priorities, and resisted complying with the Western policies as was most clearly observed in the case of the unilateral, extra-territorial sanctions of the United States. As a result, just as the case of Russia, Türkiye has had to delink its bilateral engagement with Iran from its broader place within the transatlantic security order.

Compartmentalization as a foreign policy behavior could also be observed in US-Turkish relations. While fulfilling its alliance obligations and complying with NATO decisions, Türkiye pursued cooperative relations with the adversaries of the United States in its own neighborhood, which resulted in actor-based compartmentalization (Ünlühisarcıklı, 2019). In recent years, despite its age-old alliance, growing divergence in security interests and political positions between the United States and Türkiye has compelled both parties to adopt issue-based compartmentalization to overcome the tensions in their bilateral relations (Stein, 2017a; Gümüş, 2022; Kardaş & Ünlühisarcıklı, 2021).[4]

Another example of compartmentalization to manage simultaneous operation of cooperative and conflicting dynamics in Turkish foreign policy could be observed in the case of the relations with Israel, whereby despite the tense diplomatic affairs due to the government’s support for the Palestinian cause, bilateral trade volume has continued to expand (Altunışık, 2024). Recently, Turkish-Greek relations come to the fore as yet another instance of compartmentalization of various issues in bilateral relations (Özer, 2023). Several rounds of escalation and bilateral tensions between Türkiye and Greece eventually gave way to another period of normalization whereby both states “agreed to disagree on core disputes while seeking collaboration on less contentious issues” (Nedos, 2024, para. 1). Likewise, others also studied the new phase of Turkish policy towards the Kurdistan Regional Government of Iraq after 2019, which sought to move beyond the fallout after the KRG’s referendum bid, as an instance of compartmentalization (Yıldırım, 2022). Occasionally, in policy analyses, experts continue to refer to ‘compartmentalization’ to describe Türkiye’s efforts to isolate disputed issues from the broader dynamics of its bilateral relationship, as in the examples of the Uyghur problem with China (Cafiero & Viela, 2017), or different positions on the East-Med gas exploration despite enjoying otherwise close ties with Italy (Tanchum, 2020).

3.3. Drivers of Compartmentalization in Turkish External Conduct: Systemic and Domestic Levels

It has been already underlined that compartmentalization is basically a practical strategy to manage contradictory pressures for cooperation and contention, which may arise from both systemic, domestic-state or individual-leadership level factors. In the case of Turkish foreign policy, we can talk about the following drivers:

In terms of the systemic-level drivers, two factors come to the fore. Firstly, systemic transitions present competing pressures, which need to be handled carefully. As was underlined earlier, the nature of the international system and its relationship to regional orders is an important determinant of the extent to which regional actors like Türkiye enjoy space for autonomous foreign policy action. Despite periods of frictions with the transatlantic partners and the ‘relative autonomy’ enjoyed by Türkiye (Oran, 2010), Turkish foreign policy throughout the Cold War years was overall in sync with the Western alliance system. Nonetheless, even during the height of the Cold War systemic pressures, Türkiye “resisted US pressure to enforce sanctions passed in 1980 to punish Iran for its taking of American hostages. The Turkish government, then headed by Suleyman Demirel, argued that US actions jeopardized an oil agreement previously signed by the two countries” (Stein, 2017b, p. 5).

The transition toward the post-Cold War era and the widening specter of regionalization opened up new avenues for cooperation with the country’s neighbors and the pursuit of multi-vector policies complemented by a quest for strategic autonomy (Kardaş, 2011; Kardaş, Sinkaya, & Pehlivantürk, 2025). Considering the continued Western-orientation, the growing relations with Russia and Iran, two countries which have been unable to overcome their underlying enmity with the West, have been a source of tension for Turkish-Western relations. In recent years, the debate over the transition to a post-Western world, the rise of China and the Global South, the discussions about the return of great power politics, or securitization of energy or technology point to another threshold of systemic transition. To the extent that this new era is creating another layer of pressures on the behavior of smaller and middle range powers, there is a growing resort to hedging as a preferred strategy by these powers (Pujol, 2024). Therefore, it is no surprise to see how Türkiye, too, is increasingly inclined to rely on actor-based compartmentalization, as it may become the most optimum way to manage systemic transition and sustain cooperation with countries outside of the Western order.

A related systemic factor is Türkiye’s international positioning as a ‘multi-regional’ regional power (Sayari, 2000; Kardaş, 2013). Considering its geopolitical location at the intersection of multiple regions, Türkiye is subject to dynamics of securitization and de-securitization in the Middle East, Europe, North Africa, or Black Sea contexts. While Buzan and Waever (2003, p. 394) conceptualize this unique position as one of an ‘insulator,’ Davutoğlu (2008, p. 78) defines Türkiye as “central country with multiple regional identities.” In turn, this status provides it with “the capability as well as the responsibility to follow an integrated and multidimensional foreign policy” (Davutoğlu, 2009, p. 12). As a result, Turkish foreign policy practices pursued political dialogue, economic interdependence and integration of Türkiye with the surrounding regions, which inevitably generated the challenges of reconciling contradictory pressures arising from different regional settings (Davutoğlu, 2013).

In any case, compartmentalization has emerged as a practical instrument to manage the competing pressures exerted by Türkiye’s membership into different regional sub-systems and the penetration of extra-regional powers -global overlay- into the surrounding neighborhoods. Moreover, in addition to attending to divergent priorities in different regions, Türkiye also needs to engage with certain actors in more than one region, which has further exacerbated the pressures for adjustment. For instance, Türkiye’s relations with the United States contradict its regional engagements with Russia and Iran, considering the former’s penetration into multiple regions as the sole unipolar leader. Likewise, with Russia as well, Türkiye has been engaging in more than one region, which has been accentuated by Moscow’s growing role in the Middle East and Africa. By detaching contradictory relationships, Türkiye tries to balance off rival powers against each other, or prioritize partnerships across regions.

In terms of domestic-state level drivers, Türkiye’s main strategic orientation or role perceptions (Özdamar, 2016) are important factors that have a bearing on compartmentalization behavior. Indeed, on a longitudinal dimension, national preferences for foreign policy orientations have affected the way Türkiye has responded to the changes in the global systemic conditions and how it has navigated its strategic environment through pursuit of multi-dimensionality. Turkish strategic culture has long exhibited elements of realist and liberal undertones. In the late Ottoman and early Republican period, defensive realpolitik, along with Westernization and a policy of balancing between great powers, emerged as major pillars of Turkish strategic culture (Karaosmanoğlu, 2000).

Western-orientation has been a major driver of compartmentalization in Turkish foreign policy in different periods. While it positioned itself under the US-led security order through membership into NATO, the contradictions between Western connection and Türkiye’s regional priorities and interests inevitably arose. Notwithstanding its skeptical position on the non-alignment movement or filtering its Middle East policies through Western priorities (Bilgin, 2009), when the dynamics of bloc politics started to dissipate, or when Türkiye failed to ensure its economic and security needs within the existing alliance system, it searched for new relationships. In that respect, the periodical rapprochement with the Soviet Union, especially during the 1970s, was arguably an instance of compartmentalization (Bayraktar, 2024).

The somehow inherent tensions between alliance commitments and regional interests became even more visible after the end of the of the Cold War, as a result of a shift from defensive to offensive Realpolitik (Karaosmanoğlu, 2000), growing desire for multi-axis orientation, and growing desire for autonomous action (Kardaş, 2011). Despite maintaining its place within NATO and the Western security architecture, Türkiye has hardly been willing to be ‘anchored’ as it is understood by the transatlantic partners. Thus, to the extent it has pursued independent regional engagements, which it deemed not in contradiction with NATO commitments, actor-based compartmentalization has emerged as an important instrument to address the resulting tensions.

Secondly, cooperative security has been ingrained in Turkish strategic culture over decades, partly as a result of Westernization (Karaosmanoglu, 2000). A firm believer of the notion of inclusive security and long-advocate against policies of containment or sanctions, Türkiye has preferred engagement over confrontation in its relationship with neighbors, and detached itself from its Western partners’ coercive policies. Therefore, it has engaged in actor-based compartmentalization, in an effort to minimize the negative fallout of its alliance ‘commitments’ for its regional relationships. Likewise, even in the case of neighbors with which it has deep-rooted historical enmities and underlying competitive or confrontational dynamics, it has been seeking to address them within the framework of cooperative security, whereby a regionalist approach centered on “regional ownership” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, n.d.) has played a decisive role. Acting on the motto of ‘regional solutions for regional problems,’ which was also embraced by its interlocutors, Türkiye has come to view Russia or Iran more as potential partners than a source of threat, thus giving way to issue-based compartmentalization (Köremezli, 2021, pp. 365-68).

Thirdly, the liberal elements underpinning Turkish international conduct also create incentives for the pursuit of compartmentalization. Overall, utilitarian, profit-maximizing and pragmatic considerations have a major impact on Turkish foreign policy decisions, unless vital interests are at stake. For instance, as summarized by the ‘trading state’ argument (Kirisci, 2009) domestic interest groups and commercial considerations play a major role in the formulation and execution of foreign policy. Along with the realities of interdependence and the necessity to access international markets and funds to sustain a healthy growth trajectory, Turkish economic realities dictate continuation of cooperative relations even in cases of political disputes, which again can best be reconciled through issue-based compartmentalization. As Balta points out, “increasing economic cooperation has prompted flourishing social and economic networks” which not only benefitted from but also lobbied for the rapprochement between the two countries (Balta, 2019, pp. 72-83), serving as a major driver of compartmentalization in Turkish-Russian relations. Moreover, actor-based compartmentalization also has been closely related to economic or commercial considerations, which dictated a diversification of partners outside the Western camp. As underlined earlier, since the early 1960s “facing rising inflation, a trade deficit, and declining foreign reserves, Turkey found itself compelled to explore supplementary sources of economic support” through even a compartmentalized partnership with the Soviets (Bayraktar, 2024). In the post-Cold War period, rising energy demand and the search for export markets were major drivers of Türkiye’s pursuit of multi-vector foreign policy, which forced a rethinking of its adversarial relations with mineral-resources-rich neighbors and conducting them on more cooperative foundations, despite objections from the United States and Western partners.

3.4. Individual-ideational Level Drivers: Can We Talk about Cognitive Compartmentalization?

As argued earlier, compartmentalization is an outcome of cognitive-strategic processes whereby ‘cognitive priors’ shared by the elites play decisive causal roles in policy practices. For our purposes here, the relevant question is whether compartmentalization has established itself as part of a set of cognitive priors, which affect the Turkish foreign policy makers’ formulation of alternative foreign policy strategies.

Firstly, it is possible to say that the utilitarian, pragmatic vision is shared by many Turkish decision makers as a cognitive prior. In particular, considering their specific trajectory in Turkish politics, the JDP leadership had been particularly inclined to adopt such a business-oriented outlook (Renda, 2011), which has been popularly dubbed as a ‘win-win approach’ to foreign policy. While they started their journey as the representative of the interests of small and medium scale business groups, they prioritized the economic considerations in the formulation of foreign policy priorities. As part of the ‘economization of external relations’ (Frappi, 2018), they were eager to explore ways to ‘agree to disagree,’ hence isolate divergent political positions from the potential areas of cooperation and mutual gains. President Erdoğan employed the logic of a win-win approach on several occasions, including as part of the Turkish-Greek normalization process. For instance, ahead of his visit to Greece in 2023, he remarked, “our approach to foreign policy is not a zero-sum game. We will approach Athens with a win-win mindset” (Kostidis, 2023). Likewise, while attempts were underway to reinforce the Turkish-American alliance after a series of crises in bilateral relations, after noting that “the common interests of Turkey and the United States outweigh the differences,” Erdogan argued “we hope to reinforce our cooperation with the [incoming Biden] administration on a win-win basis” (Middle East Eye, 2021). While Erdoğan reiterated the importance of mutual steps on the basis of the ‘win-win’ principle during a visit to Tehran in January 2014 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2014), he repeated the same vision throughout the years (Berker, 2024).

Nonetheless, such reliance on issue-based compartmentalization to sustain economic cooperation is hardly peculiar to the JDP era, since earlier precedents exist, which can be traced to the era of former leaders such as Süleyman Demirel or Turgut Özal. During the Cold War years, Prime Minister Süleyman Demirel, following his visit to the USSR, said “today, the mistrust, hesitations and prejudices that have overshadowed and severely damaged Turkish-Soviet relations for many years are on the way to being eliminated. Commercial exchanges between our countries have entered an increasing tempo. As in our relations with other countries, political relations should not get in the way of economic relations for any reason.” (as cited in Balta & Özkan, 2016, p. 21).

Secondly, the regionalist vision is also widely shared as one of the cognitive priors of Turkish decision makers (Kut, 2010), which in turn support compartmentalization. Within the realm of the ‘regional ownership’ principle, they aspire to uphold good neighborly relations despite historical enmities, and approach the involvement of extra-regional powers in a rather skeptical manner. Historical ties and the necessity to share the same geography with the neighboring countries in the future infuses a degree of pragmatism, which often features in Turkish leaders’ reading of regional geopolitics. For instance, at the outset of the revival of the Turkish-Iranian rivalry subsequent to the Arab Spring, then Foreign Minister Davutoğlu stated; “It is quite natural that countries sharing the same geography have a relationship of cooperation and competition. While cooperating on some issues, they can compete over some other issues” (CNN Türk, 2012). In a meeting with his Iranian counterpart Hassan Rouhani in April 2016, President Erdoğan, after reiterating the common vision between the two states to prevent bloodshed in the region, argued that “it is beneficial for our states to minimize differences and maximize commonalities by enforcing political dialogue between us” (Haberler.com, 2016), which thoroughly illustrates the logic and function of issue-based compartmentalization. In another instance, Davutoğlu argued that regional actors “should not leave the fate of the region to extra-regional powers,” (Sinkaya, 2016, p. 96) illustrating the extent to which Türkiye preferred to conduct its relations with Iran on a separate platform than those with the United States, which lays the ground for actor-based compartmentalization. Again, during his meeting with Iranian President Raisi in January 2024, Erdoğan clearly reiterated this vision when he said “we have not terminated and will not terminate our economic and trade relations with our neighbor Iran due to [unilateral US] sanctions” (Berker, 2024).

Such a regionalist perspective and emphasis on cooperative security understanding can also be traced to earlier periods. In Turkish foreign policy makers’ conceptual maps, there is constant emphasis on the indivisibility of security and the necessity of including neighbors into security governance. For instance, then Foreign Minister Murat Karayalçın, after emphasizing the close relationship between peace, prosperity, and cooperation in economic and commercial areas, argued in a 1995 essay that “solving our problems and establishing good relations with all our neighbors is one of the important principles of our foreign policy” (as cited in Kut, 2010, p. 26). Likewise, conceptualization of Türkiye as a multi-regional actor and attributing to it a quest for multidimensional foreign policy is hardly novel. The roots of a multidimensional foreign policy could be dated to the early 1960s, whereas a search for proactive foreign policy course in various neighboring regions was clearly observed immediately after the end of the Cold War. Former Foreign Minister Hikmet Çetin, for instance, stated in 1993: “Being located in the middle of this very sensitive geography embracing the Balkans, the Black Sea, the Caucasus, the Middle East and the Mediterranean brings many responsibilities to Turkey, but also offers cooperation opportunities in a wide area…that necessitate it to take initiatives for building a belt of peace and develop political and economic cooperation.” (Kut, 2010, p. 25).

Thirdly, core ideational beliefs can be considered as another cognitive factor that may paradoxically give way to compartmentalization. The JDP leadership has strong moral positions which have been affecting Turkey’s foreign relations in the case of some countries. One can talk about the pursuit of a Moralpolitik and ideational agenda on such issues as the Palestinian question, Arab Spring or Syrian civil war, which have also underscored the JDP policy elite’s sensitivity to conservative segments of its support base. However, more often than not, these ideational beliefs, which are usually treated as an instance of an ideological foreign policy agenda (Altunışık, 2024), have contradicted with the utilitarian-liberal considerations on the one hand, and Realpolitik or national interest calculations, on the other. The leadership has often resorted to issue-based compartmentalization to manage the pressures on the foreign policy making processes emerging from this mismatch between moral and pragmatic considerations (Kardas, 2006).

The most notable case in this respect is the JDP leadership’s unwavering commitment to the Palestine cause, which has been breeding the conflictual relations between Israel and Türkiye. Yet, despite years of crises in political relations, economic exchanges have continued. During different attempts to mend the ties, President Erdoğan has used the logic of compartmentalization to advocate for the normalization agenda, which was openly rejected by his domestic supporters. For instance, in December 2021, he stated that “despite our differences of opinion on Palestine, our relations with Israel in the field of economy, trade and tourism are progressing in its own way” (Türkten & Kasap, 2021). On another occasion, while addressing JDP deputies in the Parliament in April 2022, he stated, “the steps we take to develop political and economic relations with Israel as required by global and regional needs are different. Our Jerusalem cause is different.” (AK Parti, 2022) Likewise, while justifying the normalization process with Egypt after a decade of tensions due to his moral stance on Muslim Brotherhood, Erdoğan used a utilitarian logic of compartmentalization. Meeting with Sisi in Ankara in 2024, Erdoğan said that the two countries would advance their multi-dimensional relations with a ‘win-win approach.’ (TRT World, 2024)

3.5. It takes Two to Tango! Converging Perspectives on Compartmentalization

As pointed out earlier, compartmentalization at the practical level is highly contingent on the pursuit of a similar approach on both sides, as well as its adoption at a cognitive level. It must be emphasized that the rise of high-level, leader-to-leader dialogue in Turkish foreign policy practices has largely facilitated such a congruence of perspectives. Despite the underlying geopolitical differences, leaders put high premium on personal rapport with their counterparts, in addition to acting on the necessity of maintaining cooperation in certain issue areas. To the extent that this top-down, leadership dominated foreign policy style has facilitated the dampening of tensions and overcoming of disagreements, they have also enabled cooperation in areas of overlapping interest.

For instance, Turkish inclination to compartmentalize relations with Russia has been reciprocated by Moscow in a similar manner. After acknowledging the divergence of opinions on substantive issues with his Turkish counterpart Erdoğan, President Putin praised the mutual trust they had, adding that “there is one thing I know: the bilateral trade volume surpassed USD 20 billion,” which underscored the role of pragmatic calculation (Ergin, 2020, para. 11). Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov stated how despite “serious differences on a number of international issues … Russia and Turkey engage in intensive political dialogue and have developed mutually beneficial cooperation in various areas.” He added that “without downplaying the existing differences,” Russia would continue to develop cooperation with Türkiye “guided by the strategic vision of common interests” (Teslova, 2021, para. 6). In any case, considering Russia’s skillful employment of ‘frozen conflict strategy’ in its neighborhood, its ability to achieve an overlapping perspective with Türkiye around compartmentalization can be better understood.

Likewise, a similar shared vision can be detected in the case of the Turkish-Iranian relations, as nicely captured by the Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s statement: “the relations between Iran and Turkey have been based on solid foundations throughout history and the occurrence of bitter and unfortunate events has not been able to affect the relations between the two countries” (Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2020). Similarly, the Greek Prime Minister Mitsotakis, while commenting on the normalization agenda to de-escalate tensions, emphasized that despite his disagreement with the Turkish president, it is no reason not to “welcome him to Greece [to] discuss … bilateral relations… promote the positive agenda [and] not allow the difficulties we have to end up in a military confrontation” (Ekathimerini, 2023).

4. Conclusion

The widening scope of compartmentalization as a practical/cognitive behavior in the post-Cold War period was made possible by the evolution of Türkiye’s international positioning against the background of a changing international system. Moreover, a host of domestic level factors, particularly elements of strategic culture, including Westernization and regionalism, contributed to the same trend. Furthermore, at the individual-ideational level as well, compartmentalization has been ingrained into the cognitive priors driving Turkish foreign policy behavior, as it sat nicely with the prevailing role perceptions, worldviews, and normative inclinations of policy elites. As a result, it has become part and parcel of the overall foreign policy orientation in recent years, comfortably overlapping with main pillars of Türkiye’s external conduct such as proactivism, multi-vectoral foreign policy, a quest for strategic autonomy, etc. (Kardaş, Sinkaya, & Pehlivantürk, 2025). However, as the foregoing analysis has identified, compartmentalization can hardly be considered as a phenomenon of the post-Cold War era, as it was also manifested in Turkish foreign policy both at the practical and cognitive levels in previous periods.

In recent decades, the resort to issue-based and actor-based compartmentalization was grounded in several motivations. The primary drivers were pragmatic-utilitarian, since it mainly emerged as a modus operandi defining the relations with Russia and Iran, whereby issue-based compartmentalization enabled the isolation of mutually rewarding economic cooperation or energy partnership from political-strategic conflicts. To the extent such compartmentalization also helped manage asymmetrical interdependence, the deepening of cooperation became possible, as isolation of issue domains prevented the asymmetry from harming relations in other areas. Moreover, in many cases, issue-based compartmentalization was also widely employed as a practical instrument of damage minimization and conflict management, which allowed Türkiye to move beyond periods of heightened tensions in bilateral relations. Likewise, this strategy facilitated the management of the conflicts arising from mismatches between leaders’ ideational beliefs and pragmatic considerations and national interests. Furthermore, by utilizing compartmentalization on an actor- or region-based basis, Türkiye has managed to transcend conventional boundaries of alliance relationships, simultaneously entertaining economic and diplomatic engagements with various actors, and pursuing its own security interests on a segregated, issue-based and actor-based agenda.

As has been underlined earlier, conceptualized as a form of cooperation, the success of compartmentalization hinges on the ability of the parties involved to sustain cooperation in one area, despite competition or tensions in other areas. Therefore, it takes an important degree of coordination and mutual understanding to conduct bilateral relations on such a platform. For its own part, Türkiye has managed to reach such a degree of consensus with some of its neighbors, particularly Iran and Russia in recent decades. Meanwhile, in relations with the United States, Israel or other actors, this strategy has been employed occasionally.

Granted, compartmentalization is no magical tool. On its own, its employment neither means the elimination of disputes and conflictual issues between states, nor envisages a comprehensive solution for divergent positions. The recent course of Turkish-Israeli relations since October 2023 offers a good test of the limits of managing substantive disagreements through compartmentalization for an extended period of time. While issue-based compartmentalization has prevented a total collapse of bilateral relations and sustained pragmatic cooperation in various domains, it has not proved to be a panacea for resolving the underlying disputes. A number of recent trends are exerting further pressure on this policy, eroding the remaining cooperative elements even in the domains of economics, energy, or regional connectivity. For one, Israel’s conduct in Gaza and beyond in violation of international humanitarian principles and international law, which have resulted in its isolation worldwide, have challenged the core ideational beliefs of Turkish leadership such that striking a balance between moral and pragmatic considerations through compartmentalization is no longer possible. Secondly, through its revisionist posture since the fall of the Assad regime in Syria in December 2024, as manifested through its attacks on Lebanon, Iran and Qatar as well as the aggressive language of its leadership, Israel has not only emerged as the main destabilizing force in the region, but has also come to challenge Türkiye’s vital security interests. Lastly, the heightened securitization within the broader Middle East is imposing costly choices on states and narrowing the scope of compartmentalization, not only for Türkiye but also for other actors.

Indeed, when the regional security environment takes a more impermissible character, the parties may find it difficult to pursue compartmentalization. As the global forces gain predominance over regional dynamics under the influence of a return of great power competition, it may be too costly to maintain actor-based compartmentalization. Moreover, the deepening cycle of regional insecurity and the eruption of conflicts on the one hand, and asymmetric economic and power relations between the parties on the other, have put enormous pressures on issue-based compartmentalization, as isolation of disagreements against the background of heightened concerns over national interests and security competition becomes extremely untenable.

Notes:

[1] The Biden administration sought to render climate change as a distinctive issue for prospective U.S-China cooperation. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry said that the US would engage with China on climate “as a compartmentalized issue... that does not get confused by the other items” at play. (Melvin, 2021).

[2] In an interesting twist, Aybet (2006, p.541) implies the evolving meaning of compartmentalization practices. She uses ‘issue-based’ compartmentalization in the sense of dealing with Türkiye’s long-running bilateral issues such as the water issues with Syria or Aegean disputes with Greece, in separate compartments during the Cold War years. In such a setting, each compartment was handled in isolation, without having an overarching grand strategy tying individual issues together. When Türkiye started to pursue a more active foreign policy as a ‘regional power’ in the post-Cold War period, as her argument goes, the foreign policy apparatus started to create new compartments based on ‘regions’ instead, which coincided with the pursuit of a multidimensional orientation in Turkish foreign policy practices.

[3] Meanwhile, Daria Isachenko goes further and claims that compartmentalization was never the case for the Turkish-Russian relations and this incident just revealed it. (Isachenko, 2021).

[4] Regarding the contentious issues in Turkish-American relations, one of the advisers of President Erdoğan reportedly told VOA in June 2018, that “There is a process to compartmentalize issues of disagreement … Each issue is being addressed separately by working groups,” in order to prevent differences on one issue from affecting others. (Jones, 2018).

References

Acharya, A. (2009). Whose ideas matter? Agency and power in Asian regionalism. Ithaca, London: Cornell University Press.

Acharya, A. (2012). Ideas, norms, and regional orders. In T.V. Paul (Ed). International Relations theory and regional transformation (pp. 183-209). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

AK Parti. (2022, April 20). Genel Başkanımız ve Cumhurbaşkanımız Erdoğan, TBMM Grup Toplantımızda konuştu. Retrieved from https://akparti.org.tr/haberler/genel-baskanimiz-ve-cumhurbaskanimiz-erdogan-tbmm-grup-toplantimizda-konustu-20042022-141219/

Akbarzadeh, S. (2024, April 19). Iran and the nuclear agreement: What lies ahead? Middle East Council on Global Affairs. Retrieved from https://mecouncil.org/publication_chapters/iran-and-the-nuclear-agreement-what-lies-ahead/

Altunışık, M. (2024). Turkey’s foreign policy toward Israel: Co-existing of ideology and pragmatism in the age of global and regional shifts. International Politics, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-024-00619-z

Aran, A., & Kutlay, M. (2024). Turkey’s quest for strategic autonomy in an era of multipolarity. IPC Policy Brief, 1-18.

Axelrod, R., & Keohane, R. O. (1985). Achieving cooperation under anarchy: Strategies and institutions. World Politics, 38(1), 226-254.

Aybet, G. (2006). Turkey and the EU after the first year of negotiations: Reconciling internal and external policy challenges. Security Dialogue, 37(4), 529-549.

Aydinli, E., & Rosenau, J. N. (Ed.). (2005). Globalization, security, and the nation state: Paradigms in transition. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Balta, E., & Özkan, B. (2016). Türkiye-Rusya ilişkilerine “tarih” ile bakmak. (Boğaziçi Üniversitesi - TÜSİAD Dış Politika Forumu). Retrieved from https://tusiad.org/tr/yayinlar/raporlar/item/10005-turkiye-rusya-iliskilerine-tarih-ile-bakmak

Balta, E. (2019). From geopolitical competition to strategic partnership: Turkey and Russia after The Cold War. Journal of International Relations, 16(63), 69–86.

Balta, E., & Bal, H. B. (2025). How do middle powers act? Turkey’s foreign policy and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. International Politics, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-025-00679-9

Bayraktar, O. (2024). Turkey’s balancing act: The compartmentalization of security and economics. 1945-1980 [PhD Dissertation]. Bilkent University.

Berker, M. (2024, January 24). President Erdogan stresses cooperation between Türkiye and Iran to promote development, stability in region. AA. Retrieved from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/president-erdogan-stresses-turkiye-iran-cooperation-to-promote-development-stability-in-region/3117906

Bilgin, P. (2009). Securing Turkey through western-oriented foreign policy. New Perspectives on Turkey, 40, 103-123.

Brugier, C. (2024). Institutionalization, compartmentalization and “privatization” of conflicts: The driving forces behind EU-China relations, the world’s largest trading relationship. In J. F. Sabouret (Ed.). L’Asie-Monde–III: Chroniques sur l’Asie et le Pacifique (2014-2023). CNRS Éditions via OpenEdition.

Buzan, B. & Waever, O. (2003). Regions and powers: The structure of international security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cafiero, G., & Viela, B. (2017). China-Turkey relations grow despite differences over Uighurs. Middle East Institute. Retrieved from https://www.mei.edu/publications/china-turkey-relations-grow-despite-differences-over-uighurs

Cagaptay, S. (2016). Turkey’s rewarming ties with Iran. Washington Institute. Retrieved from https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/turkeys-rewarming-ties-iran

Choiruzzad, S. A. B. (2017). ASEAN as compartmentalized regionalism: A preliminary discussion. Global: Jurnal Politik Internasional, 19(1), 44-57.

Clifford, J. G. (1990). Bureaucratic politics. The Journal of American History, 77(1), 161-168.

CNN Türk. (2012, January 7). “İran’la gizli bir savaşımız yok.” Retrieved from https://www.cnnturk.com/turkiye/iranla-gizli-bir-savasimiz-yok-80487

Coffey, L., & Kasapoğlu, C. (2023). A new Black Sea strategy for a new Black Sea reality. Hudson Institute, 1-14.

Cornell, S. E. (2016). The Fallacy of ‘compartmentalisation’: the West and Russia from Ukraine to Syria. European View, 15(1), 97-109.

Çelikpala, M. (2019). Viewing present as history: The state and future of Turkey-Russia relations. EDAM Foreign Policy & Security, 6, 1-30.

Davutoğlu, A. (2008). Turkey's foreign policy vision: An assessment of 2007. Insight Turkey, 10(1), 77-96.

Davutoğlu, A. (2009). Turkish foreign policy and the EU in 2010. Turkish Policy Quarterly, 8(3), 11-17.

Davutoğlu, A. (2013, March 21). Zero Problems in a New Era. Foreign Policy. Retrieved from https://www.mfa.gov.tr/article-by-h_e_-mr_-ahmet-davutoglu_-minister-of-foreign-affairs-of-the-republic-of-turkey-published-in-foreign-policy-magazin-2.en.mfa

Délano, A. (2009). From limited to active engagement: Mexico’s emigration policies from a foreign policy perspective (2000-2006). International Migration Review, 43(4), 764-814.

Delreux, T., & Earsom, J. (2024). Missed opportunities: The impact of internal compartmentalisation on EU diplomacy across the international regime complex on climate change. Journal of European Public Policy, 31(9), 2960-2985.

Demiryol, T. (2018). Türkiye-Rusya ilişkilerinde enerjinin rolü: Asimetrik karşılıklı bağımlılık ve sınırları. GAUN JSS, 17 (4), 1438-1455.

Ekathimerini. (2023, November 13). Athens ‘totally’ disagrees with Ankara on Hamas but talks should proceed, says PM. Retrieved from https://www.ekathimerini.com/news/1224789/athens-totally-disagrees-with-ankara-on-hamas-but-talks-should-proceed-says-pm/

Erbay, N.Ö. (2021, June 24). Ankara to use compartmentalization in managing relations. Daily Sabah. Retrieved from https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/news-analysis/ankara-to-use-compartmentalization-in-managing-relations

Ergin, S. (2020, December 29). 2020’den 2021’e dış politika (1) Rusya ile rekabet, çatışma ve işbirliği el ele yürüyor. Hürriyet. Retrieved from https://www.hurriyet.com.tr/yazarlar/sedat-ergin/2020den-2021e-dis-politika-1-rusya-ile-rekabet-catisma-ve-isbirligi-el-ele-yuruyor-41700719

Erşen, E. (2017). 2000’li yıllarda Türkiye-Rusya ilişkileri: Kompartımanlaştırma stratejisinin sorunları. In G. Özcan, E. Balta, & B. Beşgül (Eds.). Türkiye ve Rusya ilişkilerinde değişen dinamikler: Kuşku ile komşuluk (pp.147-161). İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları.

Fearon, J. D. (1998). Bargaining, enforcement, and international cooperation. International Organization, 52(2), 269-305.

Frappi, C. (2018). The Russo-Turkish entente: A tactical embrace along strategic and geopolitical convergences. In V. Talbot (Ed.). Turkey: Towards a Eurasian shift? (pp. 45-69). Milano: ISPI.

Giannotta, V. (2022). The domino effect: What is Turkey’s stake in the Black Sea crisis? Trends Research & Advisory. Retrieved from https://trendsresearch.org/insight/the-domino-effect-what-is-turkeys-stake-in-the-black-sea-crisis/?srsltid=AfmBOooHnxrID3mw_OXl8AYg5BDuDOk5SGwHSbJuHu8Iwlpp8xi_XfsI

Goldstein, J., & Keohane, R. O. (Eds.). (1993). Ideas and foreign policy: Beliefs, institutions, and political change. Ithaca&London: Cornell University Press.

Gümüş, A. (2022). Increasing realism in Turkish foreign policy during post-Davutoğlu era. Insight Turkey, 24(4), 167-186.

Haberler.com. (2016, April 16). Erdoğan: İran ile Türkiye arasındaki iş hacmi artırılacak. Retrieved from https://www.haberler.com/ekonomi/erdogan-iran-ile-turkiye-arasindaki-is-hacmi-8363333-haberi/

Hale, W. (1992). Turkey, the Middle East and the Gulf crisis. International Affairs, 68(4), 679-692.

Hamilton, R. E., & Mikulska, A. (2021). Cooperation, competition, and compartmentalization: Russian-Turkish relations and their implications for the West. Foreign Policy Research Institute, 1528.

Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2020, August 9). Dr. Rouhani at the opening ceremony of the sixth meeting of the High-Level Cooperation Council: Iran-Turkey Ties have historically been based on very strong foundations. Retrieved from https://en.mfa.ir/portal/newsview/609564/Iran-Turkey-ties-have-historically-been-based-on-very-strong-foundations

Isachenko, D. (2021). Turkey and Russia: The logic of conflictual cooperation. Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik.

Jones, D. (2018, June 29). Turkey's re-elected leader eyes less tension with NATO. VOA. Retrieved from https://www.voanews.com/a/turkeys-reelected-leader-eyes-easing-tensions-nato-allies/4460599.html

Kamel, A. (1975). Turkey’s relations with the Arab world. Foreign Policy, 4(4), 91-108.

Kang, W., & Kim, J. (2017). Compartmentalized hedging in the Middle East: Turkey's alternative strategy towards Iran. Korean Political Science Review, 51(6), 53-74.

Karaosmanoǧlu, A. L. (2000). The evolution of the national security culture and the military in Turkey. Journal of International Affairs, 54(1). 199-216.

Kardaş, Ş. (2006). Turkey and the Iraqi crisis: JDP between identity and interest. In H. Yavuz (Ed.). The Emergence of a new Turkey: Democracy and the AK Parti, (pp. 306–330). Utah: University of Utah Press.

Kardaş, Ş. (2011). Quest for strategic autonomy continues, or how to make sense of Turkey’s ‘New Wave’. GMF On Turkey.

Kardaş, Ş. (2012). Turkey-Russia energy relations: The limits of forging cooperation through economic interdependence. International Journal, 67(1), 81-100.

Kardaş, Ş. (2013). Turkey: A regional power facing a changing international system. Turkish Studies, 14(4), 637-660.

Kardaş, Ş. (2019). Turkey's S400 vs. F35 conundrum and its deepening strategic partnership with Russia. GMF on Turkey.

Kardaş, Ş., & Ünlühisarcıklı, Ö. (2021). Dual Framework for the Turkey-US Security Relationship. German Marshall Fund of the United States.

Kardaş, Ş., Sinkaya, B., & Pehlivantürk, B. (2025). Scope, drivers and manifestations of the realist turn in Turkish foreign policy: A case of delayed strategic adjustment. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 25(1), 11-30.

Keohane, R. O., & Nye, J. S. (2012). Power and interdependence (4th ed.). Boston: Longman.

Kırdemir, B. (2014, August 2). Can Turkey continue to compartmentalize its relations with

Tehran? SLD. Retrieved from https://sldinfo.com/2014/02/can-turkey-continue-to-compartmentalize-its-relations-with-tehran/

Kirişçi, K. (2009). The transformation of Turkish foreign policy: The rise of the trading state. New Perspectives on Turkey, 40, 29-56.

Kostidis, M. (2023, December 2). Erdogan: ‘We will approach Athens with a win-win mindset’. Ekathimerini. Retrieved from https://www.ekathimerini.com/news/1226264/erdogan-we-will-approach-athens-with-a-win-win-mindset/

Köremezli, İ. (2021). Turkey’s foreign policy toward Russia: Constructing a strategic partner out of a geopolitical rival. Türk Dünyası İncelemeleri Dergisi, 21(2), 351-373.

Köstem, S. (2017). Türkiye-Rusya ilişkilerinde karşılıklı bağımlılığı yeniden düşünmek (Türkiye-Rusya İlişkileri Türkiye’nin Dış İlişkilerinin Son On Yılı Panel Serisi-7). ULİSA Analiz.

Kuik, C. C., & Rozman, G (2015). Introduction to light or heavy hedging: Positioning between China and the United States. In G. Rozman (Ed.). Joint US-Korea Academic Studies (pp.1-9). Washington DC: Korea Economic Institute of America.

Kundnani, H., & Puglierin, J. (2018). Atlanticist and ‘Post-Atlanticist’ wishful thinking. GMF Policy Essay, 1(6).

Kut, G. (2010). Türk dış politikasında çok yönlülüğün yakın tarihi: Soğuk Savaş sonrası devamlılık ve değişim. Retrieved from https://tusiad.org/tr/yayinlar/raporlar/item/10011-turk-dis-politikasinda-cok-yonlulugun-yakin-tarihi-soguk-savas-sonrasi-devamlilik-ve-degisim

Melvin, J. (2021, March 2). CERAWEEK: Kerry confident US can compartmentalize, work with China on climate. Retrieved from https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/electric-power/030221-ceraweek-kerry-confident-us-can-compartmentalize-work-with-china-on-climate

Middle East Eye. (2021, February 20). Turkey’s Erdogan seeks “win-win” relationship with US. Retrieved from https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/turkeys-erdogan-seeks-win-relationship-us-biden

Milner, H. (1992). International theories of cooperation among nations: Strengths and weaknesses. World Politics, 44(3), 466-496.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2014, January 30). Prime Minister Erdoğan pays a visit to Iran. Retrieved from https://www.mfa.gov.tr/prime-minister-erdogan-pays-a-visit-to-iran.en.mfa

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (n.d.). National foreign policy in the “Century of Türkiye.” Retrieved from, https://www.mfa.gov.tr/synopsis-of-the-turkish-foreign-policy.en.mfa

Mueller, P. (2013). Europe’s foreign policy and the Middle East Peace Process: The construction of EU actorness in Conflict Resolution. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 14(1), 20–35.

Mufti, M. (2002). From swamp to backyard: The Middle East in Turkish foreign policy. In R. O. Freedman (Ed.), The Middle East enters the 21st century (pp. 80-110). Gainsville: University Press of Florida.

Nedos, V. (2024, December 4). Athens, Ankara agree to disagree but keep talking. Ekathimerini. Retrieved from https://www.ekathimerini.com/politics/foreign-policy/1255265/athens-ankara-agree-to-disagree-but-keep-talking/

Oran, B. (2010). Turkish foreign policy (1990-2006): Facts and analyses with documents (trans.) Mustafa Akşin. Utah: The University of Utah Press.

Ozkarasahin, S. (2022). Walking on thin ice: Will Turkey’s ‘compartmentalization’ work in Ukraine? Eurasia Daily Monitor, 19 (154). Retrieved from https://jamestown.org/program/walking-on-thin-ice-will-turkeys-compartmentalization-work-in-ukraine/

Öniş, Z., & Yılmaz, Ş. (2016). Turkey and Russia in a shifting global order: Cooperation, conflict and asymmetric interdependence in a turbulent region. Third World Quarterly, 37(1), 71-95.

Özdamar, Ö. (2016). Domestic sources of changing Turkish foreign policy toward the MENA during the 2010s: A role theoretic approach. In C. Cantir & J. Kaarbo (Eds.), Domestic role contestation, foreign policy, and International Relations (pp. 89-104). New York: Routledge.

Özer, D.A. (2023, November 16). Compartmentalization of ties vital for Ankara, Athens relations. Daily Sabah. Retrieved from https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/news-analysis/compartmentalization-of-ties-vital-for-ankara-athens-relations

Patrick, S. M., & Bennett, I. (2014). Learning to compartmentalize: How to prevent big power frictions from becoming major global headaches. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved from https://www.cfr.org/blog/learning-compartmentalize-how-prevent-big-power-frictions-becoming-major-global-headaches

Pujol, I. G. (2024). Theorising the hedging strategy: National interests, objectives, and mixed foreign policy instruments. All Azimuth: A Journal of Foreign Policy and Peace, 13(2), 193-214.

Renda, K.K. (2011). Turkey’s neighborhood policy: An emerging complex interdependence? Insight Turkey, 13(1), 89-108.

Robins, P. (1992) Turkish policy and the Gulf Crisis, adventurist or dynamic? in C. H. Dodd (Ed.), Turkish foreign policy, new prospects (pp.70-87), Wistow: The Eothen Press.

Rudd, K. (2022). Rivals within reason? US-Chinese competition is getting sharper—but doesn’t necessarily have to get more dangerous. Foreign Affairs. Retrieved from https://www. foreignaffairs. com/china/rivals-within-reason.

Rüma, İ., & Çelikpala, M. (2019). Russian and Turkish foreign policy activism in the Syrian theater. Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi, 16(62), 65-84.

Sayari, S. (2000). Turkish foreign policy in the post-Cold War era: The challenges of multi-regionalism. Journal of International Affairs, 54(1), 169-182.

Sinkaya, B. (2014). Başbakan Erdoğan’ın Tahran ziyareti: Türkiye-İran ilişkilerinde yeni bir dönüm noktası. ORSAM. Retrieved from https://orsam.org.tr/yayinlar/basbakan-erdoganin-tahran-ziyareti-turkiye-iran-iliskilerinde-yeni-bir-donum-noktasi/

Sinkaya, B. (2016). Iran and Turkey relations after the Nuclear Deal: A case for compartmentalization. Ortadogu Etütleri, 8(1), 80-100.

Sinkaya, B. (2019). Turkey-Iran relations after the JDP. Istanbul: Institut Français d'études Anatoliennes. Retrieved from https://books.openedition.org/ifeagd/2934

Smyth, C. (2021). ‘Tick the box and move on’: Compartmentalization and the treatment of the environment in decision‐making processes. Journal of Law and Society, 48(3), 410-433.

Stein, A. (2017a). A new status quo: The West’s transactional relationship with Turkey. Heinrich Boll Stiftung. Retrieved from https://tr.boell.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/LY_E-Paper_Aaron%20Stein_v3.pdf

Stein, A. (2017b). An independent actor: Turkish foreign energy policy toward Russia, Iran, and Iraq. Atlantic Council. Retrieved from https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/An_Independent_Actor_web_0608.pdf

Tanchum, M. (2020). Italy and Turkey‘s Europe-to-Africa commercial corridor: Rome and Ankara‘s geopolitical symbiosis is creating a new Mediterranean strategic paradigm. Austria Institut für Europa-und Sicherheitspolitik. Retrieved from https://www.aies.at/download/2020/AIES-Fokus-2020-10.pdf

Taşhan, S. (1985). Contemporary Turkish policies in the Middle East: Prospects and constraints. Foreign Policy, 12(1/2). 7-21.

Teslova, E. (2021, May 24). Russia has 'beneficial cooperation' with Turkey despite differences on Ukraine: Lavrov. AA. Retrieved from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/russia-has-beneficial-cooperation-with-turkey-despite-differences-on-ukraine-lavrov/2252497

TRT World. (2024, September 4). Türkiye, Egypt partnership vital for regional peace and stability – Erdogan. Retrieved from https://www.trtworld.com/turkiye/turkiye-egypt-partnership-vital-for-regional-peace-and-stability-erdogan-18203810

Tsintsadze-Maass, E. (2024). Ontological crisis and the compartmentalization of insecurities. Global Studies Quarterly, 4(1), 1-14.

Türkten, F., & Kasap, S. (2021, December 23). Turkey sees anti-Semitism as crime against humanity: President. AA. Retrieved from https://www.aa.com.tr/en/turkey/turkey-sees-anti-semitism-as-crime-against-humanity-president/2455165

Ünlühisarcıklı, Ö. (2019, April 01). Turkey’s questionable commitment to NATO. GMF. Retrieved from https://www.gmfus.org/news/turkeys-questionable-commitment-nato