Abstract

The AKP government in Türkiye has been following a foreign policy based on values and discourses rather than power and interests. However, despite the lack of a radical change in international conditions, contrasting approaches in terms of the nature of foreign policy, strategic orientation, foreign relations, and international image have been adopted by the same government over short intervals of time. While a first period was marked by a value-laden transformation, a second was marked by righteous and romantic discourse and actions pointing to more value-based mentality. In a third period, foreign policy was guided by a logic based on a populist and opportunist approach. This paper calls each of these bases that shape foreign policy a different logic of foreign policy. Accordingly, while the logic of the first period was constructed in “the modified base logic” and led to the quest for strategic depth in foreign policy, the logic of the second became “righteous-romantic” and resulted in “strategic instability”. The logic of third, on the other hand, was shaped by its reactive form and led to “strategic uncertainty”. In this way, the paper argues that the strategic volatility in Turkish Foreign Policy can be explained by the elements that constitute the logic of foreign policy and the interactions among them.

1.Introduction

With the change of government in 2002, conventional TFP was criticized for not sufficiently utilizing Türkiye’s potential, and a search for change was begun to realize this potential. In this process, it is possible to identify three significantly different periods: 2003-2011, 2011-2016 and 2016-2023 2016-2023 [1]. During the first period (AKP-1), foreign policy was marked by reformist efforts conducted within a value-laden (influenced by values) framework, whereas in the second period (AKP-2) it was shaped by value-based ttitudes and discourses. In the third period (AKP-3), foreign policy was conducted with a logic based on populist discourses and opportunist actions. Thus, the logical framework in the AKP-1 period produced an effective foreign policy within the framework of “strategic depth” understanding. The logical construct of the AKP-2, by contrast, generated revisionist tendencies that resulted in “strategic instability” in foreign policy, and the logic underpinning the AKP-3 led to “strategic uncertainties” in foreign policy. Such unexpected and uncontrollable significant shifts in a foreign policy’s strategic appearance, in the absence of radical changes in conditions, is defined as “strategic volatility”. Turkish foreign policy under the AKP rule has demonstrated such strategic volatility.

This study argues that the failure to sustain the change in TFP by the AKP in the aimed for direction, and the subsequent strategic volatility, are related to shifts in the logic of foreign policy (LFP). In this context, the conceptual framework will be operationalized by defining the base LFP in terms of (i) power, (ii) interests, (iii) values, (iv) discourses, (v) actions, and (iv) the relations among these variables. As one might expect, these elements are drawn from realist, idealist, normative, constructivist and post-structuralist approaches. Each approach tends to functionalize one or more of these variables from a different perspective and use them as a basis for foreign policy analysis. Here, an analytical framework has been developed to evaluate the basic assumptions of these approaches. In this framework, the reason for strategic volatility in TFP is that “the base LFP”, which ensures stability and consistency in foreign policy, is disrupted by values and discourses, ultimately leading to risk-prone logics. Thus, the strategic volatility in TFP can be explained by the constitutional elements of the LFP and interactions among them. In this way, the article aims to analyze the consequences of foreign policies based on varying logics from different perspectives in relation to strategic volatility.

This study is expected to contribute to the literature by proposing a new framework of foreign policy analysis. It should be emphasized that this study is not about the problem of rationality, which has been widely discussed in foreign policy analyses, but about the logic on which foreign policy is based. Although the extent to which states act rationally is a matter of debate, it is certain that they try to act within a certain framework of logic. Moreover, despite the strong link between logic and rationality, they are not the same thing. While rationality is about inferences (knowledge, decisions) being based on reason, logic is about the way of reasoning for these inferences. In this context, the question here is not how much foreign policy is based on rationality, but what kind of rationality it is based on. Therefore, apart from the issue of rationality, a new conceptual framework is proposed here in order to outline the logic that underpins foreign policy decision-making and practice.

This article, utilizing a process analysis of post-2003 TFP from the perspective of the LFP is organized as follows: First, a conceptual framework for the LFP and its elements will be presented. To this end, the fundamental characteristics and functions of these elements, as well as interactions among them, will be defined and “the base logic” on which foreign policy is based will be clarified. This article also discusses other possible types of logic that could cause strategic volatility in foreign policy, beyond the base logic. Then, the AKP era will be divided into three periods in terms of the LFP: AKP-1 (2003-2011), AKP-2 (2011-2016) and AKP-3 (2016-2023). In each period, the characteristics and functions of the LFP elements and the interactions among them are discussed to evaluate different logics and their consequences in terms of the nature of foreign policy, strategic orientation, foreign relations, and international image as indicators of strategic volatility.

2. Conceptual Framewotk: The Logic of Foreign Policy

2.1. Elements of the LFP and Their Interactions: The Base Logic

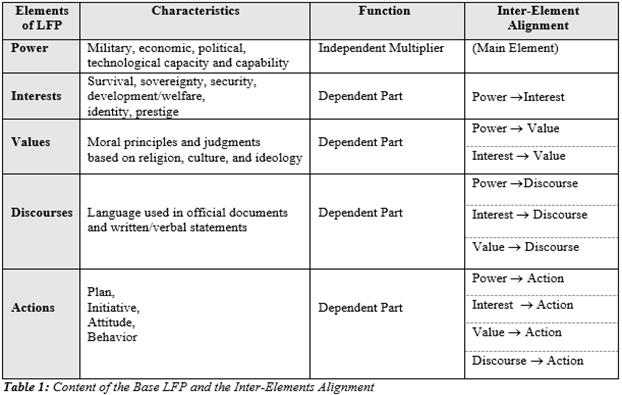

Foreign policy is a combination of design, orientation and implementation. When we look at the details of this combination, we see a number of indispensable elements such as the capacity and capability to do (power-p), what needs to be protected or promoted (interest-i), the ideals and the thoughts about the desired ends (value-v), their statement (discourse-d) and implementation (action-a). These elements and the interactions among them are the building blocks of foreign policy architecture and logic behind it. The logic of foreign policy (LFP) refers to appropriate characteristics and functions of these elements, and alignment among them. It is also assumed as a requirement of the LFP that all these are compatible with the international balances of power (bp) and normative structure (ns).

Thus, the LFP has five dimensions: power, interest, value, discourse and action. Each dimension will be discussed both in terms of characteristics and functions attributed to its constituent elements, and alignment among them. In this way, this article defines “the base logic” as a precondition for a consistent and stable foreign policy.

The first dimension is power (p). It has two aspects. The first concerns the nature and definition of power. Power determines what a state can do. Leaving aside the debates on power (see Hill, 2003, pp. 127-155), we will simply consider the multidimensional (military, economic, technological, political, sociocultural), and sustainable capacity and capability as power. This power might come in different forms, such as hard, soft and smart. Power perceived by decision makers should coincide with this definition and content. Moreover, since power is relative, a state’s position in the international hierarchy of power must also be taken into account. The second aspect concerns the relation between power and other elements. Power is an essential element of the base LFP, because decisive results in foreign policy can ultimately be achieved through power. Therefore, all others should be aligned with power, which means that power is a multiplier element independent of others (the main element) in the base LFP formula.

The second dimension is interest (i). Interests are about what need to be protected or promoted, such as sovereignty, security, development/welfare, identity and dignity, and the concrete national benefits. However, in practice, interests can be defined in different ways: one way is through power and the other is through values. For the base LFP, these interests need to be defined within the confines of power. Any definition of interests that does not take power into account heavily based on values will be considered as a problem. Therefore, interests should be aligned with power (“power-interest”) and take values into consideration (“interest-value”). This requires interest to be consistent first with power and then values. Pursuing goals beyond power (unrealistic interests) is contrary to the base LFP as it entails costs, risks and/or adventurism. Thus, interests are logically represented as “i≡i/p+v” and constitute the dependent part of the sum in the base LFP formula.

The third dimension is value (v). Values refer to the moral principles and judgments believed to be good and right, derived from religion, culture, and ideology. Values are related to ideals and thoughts, and they form the norms that guide foreign policy. They define right and wrong, good and evil, what is beneficial and what is not, and thus friend and foe. In this way, they provide a framework and guidance for the state’s ideals, with whom, and how to achieve them. Values thus define a state’s international orientation and strategic identity by producing norms to which the state adheres, and these norms in turn determine what behavior is appropriate for actors with a particular identity (Katzenstein, 1996, p. 5). This will ultimately lead a state to cooperate with states that are close to its values, or to adopt the values of the states with which it cooperates. It is also possible to use values to justify and legitimize foreign policy. In any case, values should represent the whole of society and be compatible with universal values. Thus, for the base LFP, their place and influence in foreign policy should depend on and be proportional to power and interest. Therefore, values are represented as “v≡v/p+i” as the dependent part of the sum in the base LFP formula.

Values have two aspects. The first one concerns its relation to power. For “power-value alignment”, while the goals should be aligned with the capacity to realize them, this is not always possible. This is because values are related to the ideals, and power cannot limit the adoption of these ideals. But for the base LFP, values in practice should be subjected to power. The second aspect concerns the “interest-value” relationship (see Hill, 2003, p. 303). Values always should be aligned with interests. Here, too, fundamental values and interests are expected to coincide as much as possible. However, when values and interests conflict each other, the base LFP requires values to be subjected to interests (v≡v/i).

The fourth dimension is discourse (d). Discourses are the foreign policy language and communication process that is constituted by the wording and style used in the written and oral statements of decision-makers and in official texts. The importance of discourse stems from its function. Discourses have the function of forming subjects, defining identities, setting boundaries between the rational and the irrational, the legitimate and the illegitimate (Aydın-Düzgit & Rumelili, 2019, p. 286; Ripley, 2017, pp. 3-4). As such, they play an important role in the construction of social and political reality (Holzscheiter, 2014, pp. 145-150). For this reason, they are not only an output of foreign policy but also an input, forming a legitimate basis for foreign policy and guiding public opinion. However, the use of discourses for this purpose may open foreign policy to the influences of domestic politics and thus may be a source of deviation from the base LFP. Therefore, the use of discourse for this purpose should be minimal and at a level that does not affect the overall foreign policy discourse. Moreover, discourses should be realistic, flexible and free of rhetoric. On issues that have not been decided upon and are not planned to be translated into action, one should not use idealistic, enthusiastic, harsh and rigid discourses. As such, discourse, for the base LFP, should be shaped within the framework of power, interests and values, taking into account the international balance of power and normative structure, and should be both compatible with each other and internally consistent. Therefore, discourses are represented as “d≡d/p+i+v” as the dependent part of the sum in the base LFP formula.

For the base LFP, discourses have three aspects. First, they should be aligned with power. “Power-discourse alignment” (d≡d/p) means that the language used in strategic foreign policy statements should correspond to capacities and capabilities. Discourse that is disproportionate to the power used for tactical deterrence or other purposes is undesirable for the base LFP and should be exceptional. Second, discourses require “interest-discourse alignment” (d≡d/i), and should fundamentally reflect interests. The third point concerns the “value-discourse” relationship, where values, because of their idealistic and rigid character, should not be the primary determinants of discourse. The discourse should reflect values only to the extent of the necessities of power and should coincide with interests. This can be formulated as “v≡v/p+i⇒d≡d/v”.

The fifth dimension is action (a). Actions are the concrete output of foreign policy and include all kinds of initiatives, attitudes and behaviors such as strategies, relations, diplomatic interactions, use of force, and operational plans related to them. States should possess a variety of instruments for actions, and actions should be carried out using appropriate instruments. Actions can be the product of different logics (Holzscheiter, 2014, pp. 145-150; Tabak, 2014, pp. 23-30). For the base LFP, actions are expected to emerge depending on power, interests, values and discourses and the alignment among them. Moreover, since the actions are directly oriented towards the external environment, they should -more than any other element- be in line with the international balance of power and normative structure. Therefore, actions are represented as “a≡a/p+i+v+d” as a dependent part of the sum in the base LFP formula.

Actions can be evaluated along four aspects. The first is the “power-action alignment”. This refers to the suitability of actions to capacities and capabilities (a≡a/p). For the base LFP, taking actions beyond one’s capacity is adventurous. The second is “interest-action alignment” (a≡a/i). It is important that actions match interests. An action without a clear definition of interests is a deviation from the base LFP. The third is “action-value alignment”. Actions should be aligned with values. But the transformation of values into determinants of actions with no regard of power and interest, i.e. value-based actions, is contrary to the base LFP. Only value-based actions that are aligned with power and interest are compatible with the base LFP (v≡v/p+i⇒a≡a/v) and only then can values guide actions. Fourth is “action-discourse alignment”. Discourse should not be independent of action. In foreign policy, states translate their strategic objectives into discourse and strive to realize them. In this case, actions are expected to be in line with such discourses (a≡a/d). Naturally, not everything that will be done can be said, and not everything that is said can be done. For example, a state may sometimes use tactical discourses for deterrence purpose. What is important for action-discourse alignment is to put into action what is frequently emphasized at the level of discourse and not to emphasize what will not actually be acted upon.

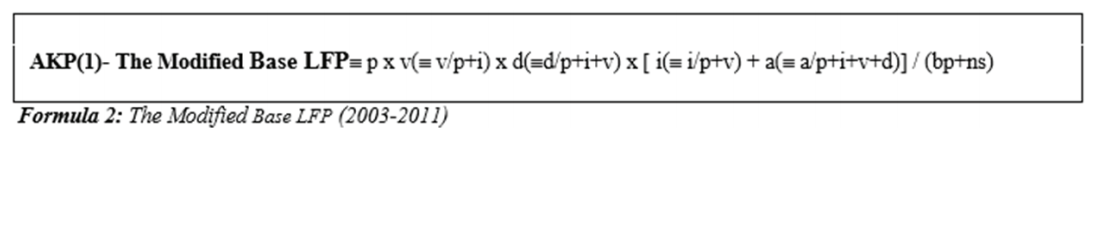

Consequently, as demonstrated in Table 1, the base LFP assumes that interests should be in alignment with power, values should be in alignment with power and interests, discourses should be in alignment with power, interests and values, actions should be in alignment with power, interests, values and discourses, and all the while taking into account the international environment (bp+ns) that are divisors of all equivalences. In this case, the base LFP would be formed as in Formula 1.

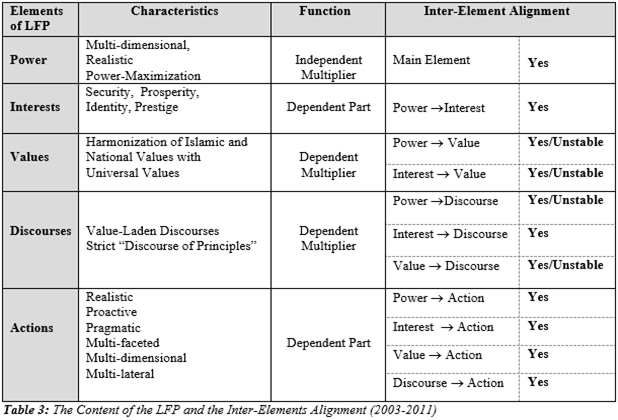

2.2.The Base Logic and The Others

States seek to conduct their foreign policies in line with some sort of the “base logic” outlined above. This logic ensures a stable foreign policy for two reasons: because, the characteristics and functions assigned to the elements of logic are (i) realistic and proper, and (ii) relations among the elements are aligned. It is assumed that conducting foreign policy on such a logic will prevent probable instability, inconsistency, uncertainty and adventurism, reduce the costs and risks of foreign policy, and strengthen its legitimacy. Moreover, this form will prevent foreign policy from personalization, short-term concerns and polemical debates and instantaneous and uncalculated reactionary behavior.

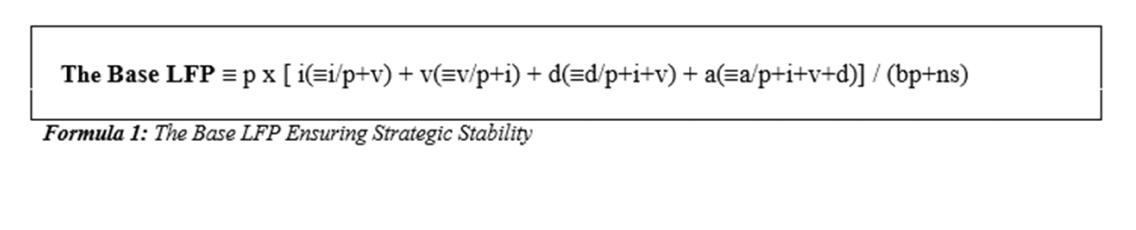

Any configuration of the LFP elements is an outcome of a different logic. Based on the change in the functions of the elements and the interactions among them, the base LFP can take on opportunistic, righteous/romantic, reactive, or adventurous forms, which can lead to more risk-prone policies and strategic volatility. As long as the foreign policy elements are aligned and power is the independent multiplier, it is assumed that foreign policy is shaped by the base logic. Within these confines, any other change in the functions of the elements, as long as they do not turn into independent multipliers over power, is also regarded as the modified base logic. Any other change that misaligns the elements and turns one or more of them into an independent multiplier over power is a deviation from the base logic.

When “interest” turns into the independent main element beside power, LFP will be opportunistic. A foreign policy based on this logic will be volatile due to the changing nature of interest. When the main element becomes “values” beside power, foreign policy is based on “righteous/romantic logic”, and when “discourse” becomes the main element, foreign policy is based on “reactive logic”. Righteous/romantic logic leads to unachievable goals in foreign policy. Reactive logic, on the other hand, undermines credibility and reliability. If interest, value, discourse and actions become the main elements over power, the LFP turns “adventurous”. These logics contain serious costs, risks and, sometimes can lead to existential problems. Therefore, they are considered as risk-prone logics deviating from the base logic, and causing strategic volatility (See Table 2).

3.The Logic Of The AKP’S Foreign Policy: Its Nature and Consequences

3.1. The Logic of Foreign Policy in the AKP-1 Period and Its Consequences

The main reason behind the logical shift in this period was the value-laden reinterpretation of Türkiye’s international role and identity in line with the AKP’s political identity. It is clear that there was a change in TFP with the AKP government, which described itself as conservative-democrat. The then foreign policy theorist of the AKP, Davutoğlu, who criticized the foreign policy understanding of previous periods for overlooking Türkiye’s potential and historical legacy, formulated foreign policy from a perspective that he termed “strategic depth” (2001). He interpreted this perspective through the lens of “history-geography-civilization”, reflecting his conception of identity, which he referred to as “self-understanding” (ben-idraki) (1997, pp. 10-11). This perspective advocates a perception of a new Türkiye and a new world. With the AKP government, this new strategic mindset based on values and identity was codified and put into practice with new principles and discourses. This change brought about both a reinterpretation of the elements of the LFP and a rearrangement of the relations among them. However, in this period, foreign policy remained relatively in line with the base logic due to the AKP’s quest for legitimacy and its EU vision.

3.1.1.Value-Laden Transformation and the Modified Base Logic

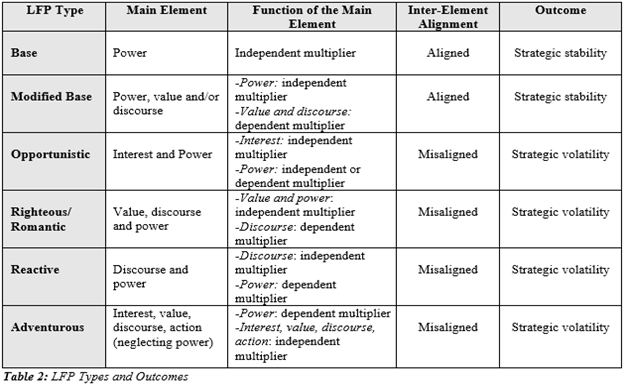

Davutoğlu criticized the past understanding of power, which is the main element for the LFP, by stating that Türkiye remained below its potential (2001, p. 45). According to Davutoğlu, power is composed of fixed data, consisting of history, geography, population and culture, and potential data, consisting of economic, technological and military capacity. His equation of power is the sum of these data multiplied by strategic mindset, strategic planning and political will (2001, p. 17). Davutoğlu stated that Türkiye needs to reinterpret all these parameters (2001, pp. 45-47). Thus, by acquiring new capabilities, an increase in power in line with the country's capacity was aimed to be achieved. As a result of the policies towards this goal, the GDP and foreign trade volume tripled in that era (Oran, 2013, p. 54). Türkiye also moved up two places to 17th in the world GDP ranking (T.C. Kalkınma Bakanlığı, 2015, p. 17). Military power also increased during this period. According to Globalfirepower data (“GlobalFirepower.com Ranks”), Türkiye’s average ranking between 2007 and 2011 was 8th, up from 20th in 2005. However, political and social fragility, which constituted a major obstacle to power capabilities, persisted throughout this period (see Oran, 2013, pp. 70-130). Despite this fragility, total power continued to increase, especially due to economic achievements. According to WPI data, the national power ratio, which averaged 0.610-0.645 until 2003, reached up to 0.680 in 2006 and 0.690 in 2011 (Ruvalcaba, 2023). Interestingly, despite this increase in power, the ratio of military expenditure to the GDP declined significantly, from an average of 3.5% until 2003 to a range of 2-2.5% after 2004 (SIPRI). This is an indication that the traditional understanding of power as defined by military capabilities has been replaced by a multi-dimensional understanding of power (Ersoy 2009, pp. 121-123). As a result, in this period, power was redefined in accordance with the base LFP and acted on by accepting that it was the main element.

In parallel with this new understanding of power, a non-status quo policy was adopted (Gül, 2007, p. 68) and definition of interests started diverging from the narrow security understanding. In line with the “strategic depth” approach, new dimensions were added to interests such as ensuring prosperity through regional integration, based on shared values, gaining prestige and thus increasing influence. All of this was attempted through the harmonization of interests within the framework of multilateralism and reciprocity. In this way, in line with the goal of gradually expanding the sphere of influence (Ersoy, 2009, p. 123), the immediate environment was transformed from a threat to a safe area, and the sphere of interest was expanded. At the same time, full membership in the EU continued to be the primary goal of the TFP (Babacan, 2008). Therefore, the definitions of multiple interests in this period were compatible with the new understanding of power and values.

In this period, the most fundamental element that both fed the demand for an increase in power and was the source of new definitions of interests was values, which also constituted the basic dynamic of change. The decision makers of the period emphasized “moral and humanitarian obligations” and values in several speeches (Gül, 2007, pp. 78, 465, 550; Zengin, 2010, p. 63). The content of these speeches pointed to an effort to harmonize Islamic, national and universal values and to the themes of justice, equality and peace in Islam, while national values were transformed into a more pluralistic and inclusive character and harmonized with universal values such as human rights, and the rule of law. Thus, in line with Davutoğlu’s approach (2001, pp. 79-93) that political culture should be harmonized with history, civilization, and universal values, a synthesis was attempted between Turkish, Islamic, and Western values (Zengin, 2010, pp. 198, 207, p. 347). In this respect, in Öniş’s words (2014, p. 214), “the underlying logic of the AKP’s foreign policy was based on a new kind of nationalism… with conservative and religious overtones, yet outward-oriented and globalist in its orientation”. However, due to the importance attributed to values, their function in the LFP had a multiplier effect, instead of being part of the sum for the base LFP. However, since both the reflections of the change were generally positive and a value-laden approach (not value-based) was adopted, the risks of this position for the base LFP did not catch any attention. As a result, despite this risk, the values were aligned with the new definitions of interests. Additionally, even if there was no problem for power-value alignment, this was due to the fact that values in foreign policy did not yet require power. However, the attitudes manifested in the Palestinian policy pointed to a serious risk for power-value alignment. The same is true for the interest-value alignment.

In this period, the discourse that was, in Davutoğlu’s words (2001, p. 46), “squeezed between sloganic Westernism and sensational third worldism” was replaced by a new discourse compatible with increasing power, expanding interests and values. This discourse was remarkable in two ways. First, it was shaped by a number of concepts such as “pro-active foreign policy” and “rhythmic diplomacy,” developed by Davutoğlu himself and presented as foreign policy principles (Davutoğlu, 2008, pp. 79-84; Yeşiltaş & Balcı, 2011, pp. 12-20; Oran, 2013, pp. 139-140). These principles, announced at the beginning of the period, were decisive in foreign policy. The prominence of discourse also changed its function within the LFP and turned it into a multiplier element. Moreover, this “discourse of principles” reduced the flexibility much needed for foreign policy practice and made it more rigid and riskier. Although the political achievements allowed these risks to be ignored for a while, the later failures would lead to new problems. For example, when “zero problems with neighbors” failed, foreign policy became the target of criticism (Askerov, 2017). This points to the risk of a power-discourse misalignment and a consequent power-action misalignment. The second striking aspect of the discourses is that they were value-laden. Placing values at the center of change makes this inevitable. Moreover, this is not only a result of the government’s need to legitimize itself and the change in foreign policy and to gain public support, but also a reflection of the rising identity politics in the world. As such, “the value discourse” was compatible with the national and international conjuncture. However, for the base LFP, value-laden discourses face difficulties in aligning with both interests and values. Moreover, the use of discourse for legitimization by values led the foreign policy to turn into an instrument of domestic politics (see Öniş, 2014, p. 214), which in turn led to a more rigid and assertive discourse. During this period, because the discourse-action alignment was relatively maintained, these negativities did not stand out, but when this alignment started breaking down, this discourse became a problem for the base LFP. In conclusion, even though the foreign policy language adopted posed risks, it did not have a negative effect on the base LFP at least until 2011.

In terms of actions, Türkiye acted in a multifaceted and multidimensional, proactive and realistic manner. Foreign policy instruments have been diversified, and actions have been conducted with suitable instruments. Additionally, attention has been paid to the alignment between actions and other elements in general. Moreover, although discourses and values have been more prominent, they have been operationalized through power and interests and in accordance with international conditions. This period’s LFP and the alignment between its elements are summarized in Table 3.

As a result, the LFP of this first period can be represented as in Formula 2. Although the base logic has been largely preserved due to the function of power and inter-element alignment, values seem to have a multiplier effect. This is a risk that could disrupt the alignment between values and other elements. The same is true for discourses, which, like values, also became a multiplier element due to their principled nature. For these reasons, it can be said that the LFP in this period was one of a “modified base logic”.

3.1.2 Consequences of the Modified Base Logic: Reformism and Toward “Strategic Depth”

TFP in this period followed a path with a reformist approach. This approach generally yielded positive results in line with Davutoglu’s “strategic depth” approach. In terms of its nature, TFP had become realistic, value-laden, opportunity-oriented, multi-dimensional, in line with great powers, soft power-based, proactive, neutral or multi-lateral, and dynamic.

The reformist approach also influenced Türkiye’s strategic orientation towards a “balanced Westernism,” compatible with universal values and great powers. Although relations with the EU gained new momentum with the candidacy for full membership in general, Türkiye handled its relations with the West more pragmatically and sought alternatives in the non-western regions. As Oğuzlu (2008, p. 5) points out, “Turkey has increasingly embraced a new strategic thinking in its relations with the West that is based more on cost-benefit calculations than on identity-related factors”. In addition, Türkiye’s approach to the international system also moved away from the conformism of the previous periods, and towards more reformism. This approach came with a demand for recognition as a “central country” and a change in its international role and position.

In terms of foreign relations, a serious reform process was undertaken and efforts were made to establish multidimensional and multilateral relations based on cooperation and friendship with all actors, including historically troubled and neglected countries. Bilateral relations were diversified, developed and deepened, especially with the neighboring countries. This widening and deepening of relations was reinforced by Türkiye’s involvement in international and regional organizations.

Thus, in terms of its international image, Türkiye’s visibility, influence, prestige and attractiveness increased. The fact that Türkiye received the support of 151 states in the vote for membership of the UN Security Council for 2009-2010 is an indication of this (UN General Assembly, 2008). This shows that Türkiye had achieved a tremendous “geopolitical expansion”. As a result, Türkiye started to be characterized as a model actor in its region and achieved a “middle power” status in the international power hierarchy (Öniş & Kutlay, 2017, pp. 170-174; Çakır & Akdağ, 2017, p. 352). The effects and consequences of the change in the LFP during this period are summarized in Table 4.

The success of this foreign policy, which was appreciated by many segments of the public, became possible due to the realistic formulation of the LFP considering the potential of the country and a well adaptation to the new conditions. Nevertheless, the risk caused by the prioritization of values and discourses over power began to show its effect in this period. Especially, harsh rhetoric against Israel, the efforts to protect Iran, and the growing relations with Islamic countries led to greater value-based evaluations and criticism. In this respect, towards the end of the period, skeptics claimed that TFP was “neo-Ottomanist” (Taspinar, 2008; Onar, 2009; Ruma, 2010, pp. 133-140; Oran, 2013, pp. 196-200) and that it had led to an “axis shift” (Keyman, 2010; Çandar, 2010; Kardaş, 2011, pp. 19-42; Demirtaş Bagdonas, 2012, pp. 111-132; Oran, 2013, pp. 193-194). Even though the decision-makers explicitly rejected such criticisms, this does not change the fact that a “value discourse” had come to the forefront in foreign policy and posed problems. Indeed, the 2009 Davos Crisis, when Israel was “put in its place” with value-laden discourse, and the subsequent crises with Israel signaled the transition to a new era, one in which value-based discourses and actions would become more prominent. These debates would intensify in subsequent periods, due to value-based foreign policy.

3.2.The Logic of Foreign Policy in the AKP-2 Period and Its Consequences

The main reasons behind the logical shift in this period were the Arap Spring and Davutoğlu’s new position in the decision-making process. The start of this period was marked with Türkiye viewing itself as an “order-building actor” and a “wise country” that could redesign its immediate region and that had global ambitions (Davutoğlu, 2011a; Yeşiltaş & Balcı, 2011, pp. 18, 23). During this period, when Davutoğlu’s position in the decision-making process was strengthened (Foreign Minister in 2011 and Prime Minister in 2014), the most important development that affected the TFP and tested this claim was the Arab Spring. Despite the uncertainties, new threats and risks that emerged in this process, Türkiye asserted its claims even more strongly and declared that the TFP would be carried out with the principles of being “value-based”, “vision-oriented”, “self-confident” and “autonomous” (Davutoğlu, 2012a, pp. 3-5). However, conducting foreign policy along these principles should still be based on power and in alignment with interests. Here, we can look at how far these requirements were fulfilled for the base LFP and how these claims transformed it.

3.2.1.Value-Based Discourses and Actions, and the Righteous-Romantic Logic

Although Türkiye’s total power growth continued with the momentum of the previous period until the end of 2013, serious problems began to emerge in the elements of power. In 2013, the Gezi and December 17-25 incidents and the failure of the Kurdish Resolution Process caused significant fractures along the country’s political and sociocultural fault lines and led to instability and polarization. This had a negative impact on “political will”, which Davutoğlu considers one of the multipliers of power, and “economic capacity”. As a result of these problems, the GDP started to decline. The same was true for military power. Türkiye’s average ranking between 2012 and 2016 descended to 9th from the previous 8th (“GlobalFirepower.com Ranks”). Moreover, the political and economic situation negatively affected Türkiye’s soft power. As a result, in WPI’s national power index, the increase in total power stopped and declined slightly (Ruvalcaba, 2023). Despite all this, the assumption throughout the period was that “the country was on its way to becoming a global power” (Davutoğlu, 2011b). As a result, power gradually moved away from being determinant of the LFP. As a matter of fact, Davutoğlu stated at the beginning of the period, “We will not think about whether we can afford it. If our power is not enough, we will create the means that our power will be enough” (2011b), indicating that power would not be taken as the main factor. This is an attitude contrary to the base LFP.

In this period, interests were defined not in terms of capabilities, but wishes. In other words, Türkiye started to define its interests around values and establish spheres of influence through the prestige it had gained in the previous period in geographies that it believed shared common values. Seeing itself as an “order builder” with the opportunity provided by the Arab Spring, Türkiye wanted to establish a strong “sphere of influence” in the Middle East as a regional leader. This understanding of interest actually included the entire “near land basin”, which Davutoğlu saw as the primary sphere of influence and which he said should be gradually expanded, especially towards the Balkans and the Middle East (2001, p. 118). In fact, as Davutoğlu pointed out “the greatest national interest is the place you occupy in the conscience of humanity” (2011b), representing common interests of humanity on a much more idealistic level. Although this was a vague and romantic definition of interest, it exemplified the determinism of values over interests which is contrary to the base LFP.

In this period, alongside universal values, we see an emphasis on local values, such as the brotherhood of Muslims, fraternal law, and tarihdaşlık (sharing the same history). But, since one of the new principles was that of value-orientedness, it became inevitable that values casted more influence on policy. Thereafter, Davutoğlu emphasized values in many of his speeches and stated that a value-based foreign policy would be pursued (2012b; 2013). Thus, values became as much an independent multiplier in the LFP as power. This means that values would not be defined by power and interests, but even vice versa. Indeed, in this period, values functioned to compensate power based on the thought that a zone of security, influence and prosperity could be created around Türkiye through values. But this approach was not realistic. For this, Türkiye had to align with the values itself (Öniş, 2014, pp. 216-217), and these values had to be shared by other actors. Instead, during this period, domestic developments contradicted these values (Ayata, 2014, pp. 108-109), and no actor based their relations on these values (For an assessment, see Oğuzlu, 2012, pp. 8-17). Furthermore, Türkiye did not have enough power to support its value-based stance and to convince other actors in this direction. Therefore, there was a clear misalignment among values, interests and power. Moreover, at a time when even the great powers were acting with realpolitik concerns and ignoring universal values, Türkiye’s value-based policy neglected the balance of power. As a result, values turned into an independent multiplier like power and started to shape other elements, thereby upsetting the alignment in the LFP, and the TFP drifted away from the base logic to a righteous one.

The dominance of values disrupted the alignment of discourses and the other elements, making it value-based and romanticized (d≡d/v), and causing it to gain a multiplier effect within the LFP. When the most prominent feature of the discourse was its value-basedness, its main function was also to justify and legitimize value-based foreign policy. This function, in turn, transformed the discourse into rhetoric which manifested itself in an assertive, persuasive and enthusiastic style. In this context, it was frequently stated that Türkiye would not shy away from responsibilities required by universal values. At the beginning of the period, Davutoğlu stated that “Türkiye would raise its voice everywhere in the world” and that it would “be the defender of universal values... integrate with humanity”, “embrace what no one else has embraced” and “know no boundaries... in terms of integrating with traditional values... embrace brotherly peoples... with historical compatibility” (2011b). Moreover, emphasizing “historical missions and ties” and “obligations” and claiming to be “the pioneer and manager of the wave of change in the Middle East” (see Oran, 2013, pp. 219-222) are discourses reminding of the great power perspectives. These speeches, without the backing of great power capabilities, caused a discourse-action misalignment. Another characteristic of this rhetoric is that domestic and foreign policy discourses are often intertwined and linked. Typical examples were Erdoğan’s enthusiastic greetings to the peoples of fraternal countries when he won the 2011 elections, saying “today...Sarajevo has won, Damascus has won, Beirut has won, Gaza has won, Jerusalem has won...” (Hürriyet, 2011a), in another speech he said “Syria...is our internal affair” (Hürriyet, 2011b), and again “we will go to Damascus very soon...and will pray in the Umayyad mosque, too” (Hürriyet, 2012a). These words clearly show that the AKP was intending to be even more assertive in foreign policy with more self-confidence due to its electoral victory at home. Moreover, the legitimization and activation of the value-based foreign policy through the internalization of the outside world led the discourse to become more romanticized, raised expectations both at home and abroad, and increased the risks for TFP. Enthusiastic crowds began to see Türkiye as the savior of the peoples in the Middle East and even of the Muslim world. This led to an increasingly romanticized foreign policy.

In this period, idealistic, righteous, and biased actions were undertaken in line with value-based foreign policy. Thus, the former “pragmatic-proactivism” was transformed into “romantic hyperactivism” with a revisionist character. In this context, there were calls for the Sykes-Picot order to be changed and the “century-old parenthesis should be closed” (Karagül, 2013). Erdoğan’s visits to Libya, Tunisia and Egypt in September 2011 and subsequent efforts to restructure these countries (Ayata, 2014, p. 99) reflect this revisionism. The most prominent example of this revisionist tendency was Syria. After failing to convince Assad for political reforms, Türkiye became a direct party to the civil war and attempted to overthrow Assad (Yeşilyurt, 2013, pp. 420-421). For the first time in its history, Türkiye directly intervened in the internal affairs of another country and tried to shape it without taking international law into account. This direct meddling and over-engagement, which was also evident in the cases of Libya and Egypt, led to foreign policy being conducted like domestic affairs. For instance, Erdoğan directly addressed the crowds in Libya and Egypt in 2011, identifying with them and delivering strong messages of unity and solidarity (Haberler.com, 2011a, 2011b). But Türkiye had to change its policies in a short period of time in the face of unforeseeable and uncontrollable developments (see Ayata, 2014, pp. 100-106). Thus, causing Türkiye to directly confront the great powers in the region, these policies generated inconsistent actions.

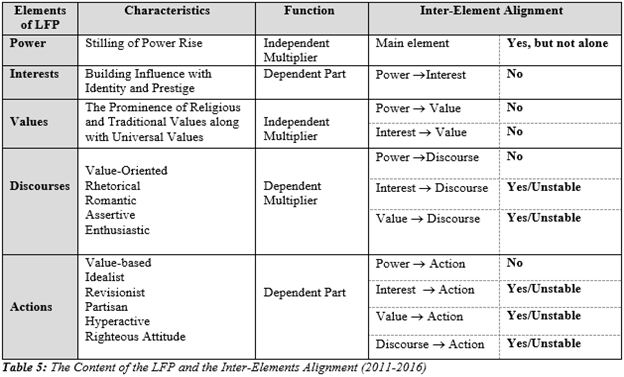

Such value-based actions are coined as a “principled stance”, implying that principles representing certain values, regardless of power, interests and the international environment, should be maintained resolutely. After 2011, both Erdoğan and Davutoğlu insisted that Türkiye had adopted a “principled stance” in the face of most events. According to Davutoğlu, Türkiye “mobilizes the global conscience with its principled stance” (Yılmaz, 2013). By adhering to this stance, Türkiye challenged the injustices produced by the international system and positioned itself as the protector and voice for the oppressed. Its strong support for the Palestinians against Israel (Yeşilyurt, 2013, pp. 429-433, 442-446), and Iran against the US sanctions (Yeşilyurt, 2013, pp. 455-458), its criticisms of the structure of the UN Security Council (Milliyet, 2013), its humanitarian aid, advocating the rights of Syrian civilians against the regime and unconditionally opening borders to refugees regardless of the costs, etc. all were reflections of a “principled stance” around values such as justice, brotherhood and freedom. However, due to the neglect of power and systemic conditions, these value-based actions had to face reality and started wavering. For example, while criticizing NATO’s intervention in Libya in February 2011 (Hürriyet, 2011c), it became a part of the intervention in May. This period’s LFP and the alignment between its elements are summarized in Table 5.

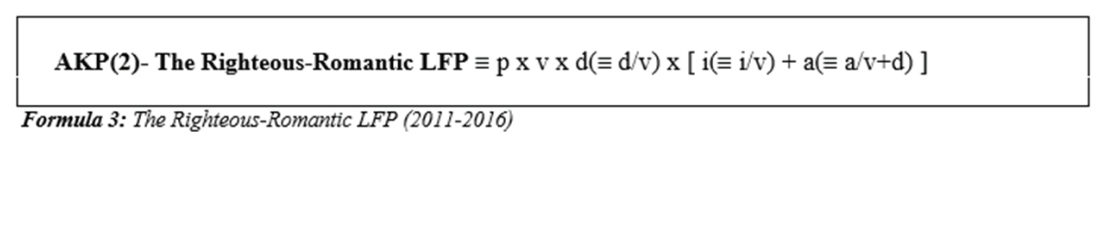

The LFP completely changed after 2011, as demonstrated in Formula 3. Here, values are no longer a factor dependent on power and interests, but have gained a multiplier effect as an independent factor, just like power. So, just as values are the main determinant of interests (i≡i/v), discourse is now shaped on the basis of values (d≡d/v) and has gained a multiplier effect as well. In this case, the influence of values and discourse on actions inevitably increased (a≡a/v+d) and foreign policy took on a “value-oriented discourse”. Additionally, this foreign policy also neglected the international balance of power (bp) and normative structure (ns). Therefore, “bp+ns” is no longer included in this formula. Thus, TFP began to be conducted on the “righteous-romantic logic” instead of the modified base logic. In Aras’ words (2019, p. 8) “The ideational richness without capacity ended up with an approach of a rhetorical and, historicist-romantic understanding”. 3.2.2.Consequences of the Righteous-Romantic Logic: Revisionist Tendencies and “Strategic Instability”

3.2.2.Consequences of the Righteous-Romantic Logic: Revisionist Tendencies and “Strategic Instability”

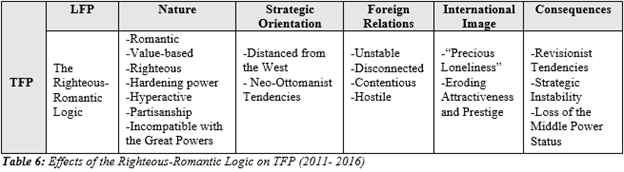

Based on the righteous-romantic logic, TFP began to be conducted with an understanding that can be described as soft revisionism. Decision-makers’ frequent appeals to the Ottoman geography and peoples, their references to historical heritage and responsibilities, and their view of the “order-building” role as a historical necessity, reflect a revisionist understanding with a neo-Ottomanist character (see Yavuz, 2022, p. 670). Although this understanding faced the compelling and limiting influence of systemic factors, it was not adapted to the changing conditions (Yeşilyurt, 2017). This attitude, which represents the practical counterpart of the strategic depth understanding, ultimately led to “strategic instability” in foreign policy; manifested in contradictions and swings from one extreme to the other within the same period in terms of indicators of strategic volatility.

First of all, the replacement of reformism with revisionism shifted the nature of TFP. In particular, when its value-laden characteristic became value-based and righteous, other attributes also changed rapidly. Realism was replaced by romanticism, compatibility with the great powers turned into rivalry, soft power turned into hardening power, opportunity-orientedness became opportunism, proactivism became hyperactivism, and neutrality turned to partisan interventionism.

Secondly, although there was no significant change in Türkiye’s strategic identity, its position in the Western alliance became questionable, and a search for alternatives began in this period. Relations with the EU became destabilized and the SCO was seen as an alternative (see Erşen, 2013, p. 22), while relations with the US, which developed under the “model partnership” until 2011, became unstable and completely deteriorated from 2014. Thus, Türkiye began to search for its own axis. This strengthened the neo-Ottomanist tendency, and a drift from Westernization to neo-Ottomanism began.

Thirdly, after 2013, while Türkiye sustained its “principled stance,” foreign relations started to drift, as other actors operated on a realpolitik basis. While relations with the West deteriorated, relations with the Middle East were deadlocked (see Yeşilyurt, 2017, pp. 75-76). Relations with Egypt and Syria were completely severed; those with Iran deteriorated seriously; and those with Iraq also entered a crisis in 2012 because of Davutoğlu’s visit to Kirkuk and his direct relations with the Kurdistan Regional Government (Hürriyet, 2012b). Similarly, relations with Russia deteriorated gradually during the Syrian crisis and finally reached the point of sanctions in 2015 with the downing of a Russian plane. In short, both bilateral relations and the policies pursued during this period swung from one extreme to the other on the friendship-hostility pendulum.

Finally, “the principled stance” also damaged Türkiye’s international image and isolated it. Türkiye’s attractiveness and prestige became greatly eroded. This situation, which Davutoğlu justified by saying “rather than standing in the wrong place, we would stand alone and upright” (Sabah, 2013), is also referred to as “precious loneliness” (Çandar, 2013; Şener, 2013; Çelik, 2016). With this loneliness, Türkiye’s international prestige and influence were weakened and in 2014, as a candidate for membership in the UN Security Council, the country received only 73 votes as opposed to 151 in 2008. Foreign Minister Çavuşoğlu’s explanation of this was “we could not give up our principles to get more votes” (BBC, 2014).

TFP in this period was characterized by values, discourse, and a soft revisionism, which led to instability and geopolitical contraction due to miscalculations regarding systemic conditions (see Yeşilyurt, 2017). Thus, Türkiye lost clout as a middle power (Öniş & Kutlay, 2016, pp. 174-178). The effects and consequences of the change in the LFP during this period are summarized in Table 6.

3.3. The Logic of Foreign Policy in the AKP-3 Period and Its Consequences

The main reason behind the logical shift in this period was the reaction toward the West in the context of the July 15 coup attempt and subsequent domestic developments. In 2016, while the negative effects of the Syria developments were ongoing, Davutoğlu lost his position and influence in the decision-making process. After Davutoğlu, there were two major developments that once again shook the base LFP and led to a new era: the July 15 coup attempt and the transition to a presidential system. The widespread belief that Western powers were behind the coup attempt, coupled with subsequent domestic political changes incompatible with the West, strengthened the anti-western attitude. These developments also weakened the country’s ties to universal values and Western identity. Moreover, the new system of government also led to significant changes in the decision-making process, making the president the sole decision-maker in foreign policy reshaping the LFP.

3.3.1.Populist Discourses-Opportunist Actions and the Reactive Logic

For power, Türkiye’s weakening influence and emerging fragility, accompanied by one-dimensional (military) politics, were the main features of the post 2016 era. Political will and strategic planning as the sources of power, envisioned by Davutoğlu, became even more problematic. Although it was thought that strong leadership with the new form of government would have a positive impact on foreign policy, this did not happen as the decision-making process became too personalized. In addition, social and political polarization due to the state of emergency and refugees led to serious problems in these dimensions of power. In parallel, there was a serious decline in democracy, freedoms and the rule of law, as can be seen from the international indices. According to the EIU Democracy Index, while Türkiye was ranked 87th in 2012, it remained below 100th throughout the AKP-3 period (Our World in Data). According to the Rule of Law Index, Türkiye was ranked as high as 69th in the previous period, but later declined to 110-120 range after 2016 (World Justice Project). In the Freedoms Index, despite being in the 80s earlier, it dropped to the 120s after 2016 (Freedom House). The economic repercussions of all these developments have also negatively affected power. The economic problems turned into a crisis in 2020, and the previous rank of 16th in the world GDP ranking, fell to 20th. In the following years, Türkiye moved up a few places again, but economic fragility persisted. After 2016, the most important positive developments in terms of power were in the defense industry, where significant investments are made. Nevertheless, Türkiye’s average ranking in military power indices declined slightly until 2024 from the 9th to the 10th place (“GlobalFirepower.com Ranks”). Therefore, we can speak of a slight downward trend in total power. According to WPI, total power of Türkiye dropped several places in the rankings between 2017 and 2022 (Ruvalcaba, 2023). Ultimately, the relative decline in power rankings combined with socio-political and economic vulnerabilities jeopardized the sustainability of military power growth. Nevertheless, the populist discourse ignored these vulnerabilities and emphasized the advancements in the defense industries as an indicator of an increase in total power (p≡p/d). As a result, power was distorted by moving away from a multidimensional and realistic understanding, and hard power came to the fore.

In terms of interests, a focus on threat perceptions and national security gave the perceptions of interests an extremely variable character on the basis of opportunism. The trauma of July 15, the exclusionary attitudes of regional actors, the US sanctions and its support for the YPG in Syria all increased threat perceptions. As a result, TFP became rapidly securitized and moved towards balancing strategies (Kubicek, 2022, p. 649). Although a “proactive security policy” (Yılmaz, 2021, p. 158) created some opportunities, security ultimately became the overriding focus of foreign policy (Haugom, 2019, p. 210). However, the fact that the defined interests were in conflict with both the great powers and the other regional actors increased the risks in TFP. The effort to manage these risks led to a constant shift of interests along with opportunistic approach, thus a destabilized foreign policy. Moreover, the ambiguous definition of interests and goals in relations with Russia, with which it has conflicting interests on many fronts, made the situation even more problematic. However, the increase in military power and the opportunistic attitude veiled the power-interest misalignment that these ambiguities in interests could have caused. It should also be noted that discourse had a crucial effect in the veiling of this misalignment. So we can logically illustrate these as “i≡i/p+d”.

In this period, although values seemed to be a crucial TFP input, they were more of an instrumental element. In other words, values were actually used to cover up problems and consolidate public opinion rather than shaping policy and determining/reflecting the country’s strategic identity and orientation. This instrumentality, due to the impact of July 15, led to the incorporation of certain unspecified “national and indigenous” values alongside universal values. Indeed, Foreign Minister Çavuşoğlu insisted throughout the period that Türkiye acted with national and humanitarian values, and that the anchor of foreign policy was national and universal values. (2017; 2018, 26; 2019, p. 16). Erdoğan also made similar emphases (Erdoğan, 2022, pp. 20-21, 25). However, these claims actually exhibited post-truth characteristics, referring to how emotion and beliefs have a greater influence on public opinion than objective facts. Because their anti-Western yet universal, and universal yet “national and indigenous” nature highlighted the contradiction in values, this showed that they were not the real anchor of TFP. Due to the distancing from universal values at home, values actually became part of a populist discourse in domestic politics. Thus, values were shaped by populist discourse within a post-truth framework (v≡v/d). Values have other problems as well. For instance, claiming to be based on values despite the weakening of power shows that a power-value misalignment persists. In terms of the interest-value alignment, despite the emphasis on values, interests were virtually stripped of values, which allowed for a highly opportunistic foreign policy. As will be discussed later, the fact that actions generally did not match values, weakened the claim that foreign policy was based on values.

During this period, discourse became the most important element of the LFP, and its rhetorical character increased. Moreover, this rhetoric was contradictory and instrumental in many ways. The language of foreign policy emphasized principledness and universal values; paradoxically, however, it was also based on anti-Westernism and nationalism. Other characteristics of the rhetoric were reactive, harsh and sharp, as well as leader-oriented, conspiratorial, populist and post-truthist. The common perception that the West did not show enough solidarity with the Turkish government during the coup attempt, and even that it had been a conspiracy of the US and some Arab states, hardened the rhetoric against the West (see Balta, 2023). This was also a result of an ideological shift from conservative democracy to nationalist conservatism (Aras, 2019, p. 10). In this context, despite NATO membership and the claim to be bound by universal values, the ambition to join organizations such as the SCO and BRICS resulted in a serious value-discourse misalignment. Additionally, with the ideological shift, populist nationalism shaped the rhetoric, as in the case of the “national and domestic foreign policy”, the motto of this era (Çavuşoğlu, 2017, 2018).

Another characteristic of the rhetoric is that it was highly leader-centered. Reflecting the change in the governance system in 2017, all speeches used phrases like “under the leadership of our President...” and “in accordance with the priorities set by our President...” (Çavuşoğlu, 2019, pp. 14, 33). This shows that foreign policy, which had been personalized in previous periods, turned completely leader-centered, with the rhetoric being shaped according to Erdoğan’s personal perceptions and preferences, and the boundaries between domestic and foreign policy becoming more blurred (Aras, 2019, p. 10). This situation, which manifested itself in a rigid, defiant and confrontational language, led to an increase in discourse-action misalignment. For example, in the Pastor Brunson case, despite Erdoğan’s insistent statements that he was a terrorist and would not be handed over to the US, Brunson was released and returned to his country within a few months of these statements.

Another striking aspect of this rhetoric was its conspiratorial nature as a result of populism (See Balta et al., 2021). In many of his speeches, Erdoğan spoke of “master minds”, “dark hands”, or “foreign powers to stir up our country”. Bahçeli, the leader of MHP, the nationalist partner in the government, also securitized the language of foreign policy by calling even the most ordinary political issues as a “problem of survival” (Yener, 2019) and every criticism as “treason”. Even though all of these could be interpreted as domestic consolidation efforts in the post-coup attempt era, this use of language gained further prominence mostly to cover up the problems and contradictions in foreign policy and prevent criticism. This also provided convenience in managing sudden changes as part of opportunist policies. So, the rhetoric functioned as a medium between the reality and the needs of the government to convince the public. But, this rhetoric detached the elements of the LFP from reality and exacerbated misalignment among them. For example, despite the actual declining of total power, the increase in power was discursively constructed by emphasizing the achievements in the defense industry, and the public opinion was shaped through the accusative language (one of the popular discourses was “perception management”). This made it possible to pursue a foreign policy that neglected power capabilities and avoided taking responsibility for the resulting outcomes. Similarly, as in the case of the frequent expressions that the ECHR judgments were “not recognized and deemed null and void”, the constant emphasis on universal values, even when the universal values had been violated, implied an effort to veil the value-discourse misalignment. As such, TFP basically became a field of populist discourse (see Balta, 2020; Özpek & Tanrıverdi, 2018) based on a post-truth understanding. Thus, discourses gained an independent multiplier effect within the LFP, shaping other elements, which ultimately distorted the base logic.

The actions in this period were largely shaped by the responses to emerging problems and crises, which were generally reactive, defensive, opportunist and coercive. The mostly unilateral and variable actions led to misalignment among interests, values and discourses, and thus diverted from the logic of actions. First of all, with some exceptions, such as asylum seekers and foreign aid, a value-action misalignment was striking. The increasing problems regarding human rights and freedoms at home and the harsh criticism by the West further weakened the claim to acting on the basis of universal values. More importantly, many issues that were opposed in principle previously as a matter of values were turned into bargaining chips in bilateral relations. Balta (2023) calls this “give-and-take (alverci) foreign policy”. In this respect, the principled objections to Sweden’s NATO membership were removed in exchange for the purchase of F-16s from the US; Pastor Brunson was released as a result of Trump’s threats; the detention of German citizen Deniz Yücel was ended after negotiations with Germany; the Khashoggi murder case was closed as a result of negotiations with Saudi Arabia; and a meeting was had with Egyptian President Sisi, despite the fact that President Erdoğan said he would never meet him. This rapid change of actions cannot be explained merely by the changing nature of interests, but by a value-free opportunism which ended up with a value-action misalignment.

Relations with Russia during this period, on the other hand, had serious problems for value-action as well as interest-action alignment. Türkiye’s claims to take national and universal values as anchors of foreign policy, while establishing strategic relations with an authoritarian and aggressive Russia, caused misalignment between values and actions. Additionally, contradicting its Western connection, Türkiye’s strategic cooperation with Russia as in the cases of the S-400s and the Nuclear Power Plant Project, despite its conflicting interests in many regions, led to an interest-action misalignment (Yavuz, 2022, p. 675). Moreover, for economic interests, Türkiye’s anti-Western stance, when it had 60% of its foreign trade with the West and 20% with Russia, deepened this misalignment.

Another logical inconsistency was between discourse and action, which manifested itself in a mixture of cooperation and a rhetoric of enmity and conflict in its relations with some actors such as the UAE, Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Similarly, despite being anti-Western in rhetoric, the country maintained strong economic and political relations with the West and with Israel. In Balta’s words, (2023) “While Türkiye didn’t refrain from criticizing Israel... it didn’t cut trade or diplomatic relations... This discursive sharpness, which didn’t turn into action… calmed the anger of public opinion by giving the impression that Türkiye was pursuing foreign policy with its head held high, …made it possible for Türkiye to pursue a pragmatic foreign policy that constantly shifted direction”.

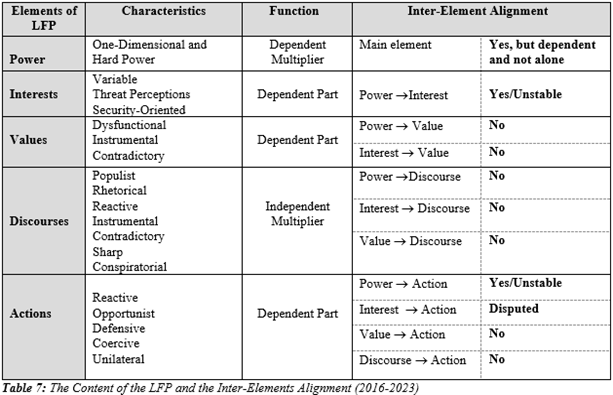

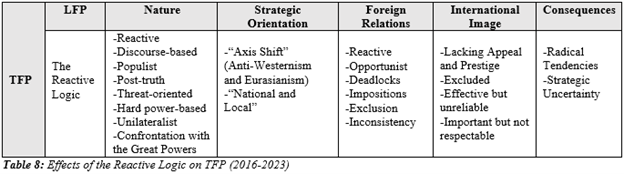

Finally, Türkiye took some unilateral military actions to overcome its geopolitical exclusion such as establishment of military bases in countries like Somalia and Qatar, military operations in Syria, military exercises in the Eastern Mediterranean within the framework of the “Blue Homeland” doctrine, as well as exclusive economic zone and Navtex declarations backed by military capabilities, sending troops to Libya and providing advanced military support to Azerbaijan to retake Karabakh. Taking these actions despite serious problems in total power may suggest a power-action misalignment. However, these actions were not examples of power-action misalignment because of Türkiye’s growing military capabilities and the effective use of diplomacy, achievement of a certain level of strategic autonomy (Haugom, 2019, pp. 211-212). Furthermore, these actions were compatible with the international environment, albeit with difficulty, through an opportunistic and delicately balanced policy. On the other hand, the fragility in total power posed a serious risk to the sustainability of this compatibility. This period’s LFP and the alignment between its elements are summarized in Table 7.

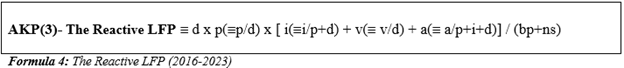

As a result, the post-2016 LFP takes a different form, as seen in Formula 4. Here, power is no longer an independent multiplier, but a multiplier that is predominantly constructed through discourse. Values have lost their impact and become part of the sum, largely because they remain in the discourse as legitimizers. In this way, discourse has become an independent multiplier determining the LFP. As a result, the interests and actions will inevitably be shaped by the discourse. In the end, LFP diverged increasingly from the base logic and transformed into the reactive logic.

3.3.2.Consequences of the Reactive Logic: Radical Tendencies and “Strategic Uncertainty”

Radical tendencies appeared in the TFP on the reactive logic, manifesting as a paradigmatic questioning of strategic identities, interests, and actions. The strategic instability observed in the previous period gave way to “strategic uncertainty” in foreign policy, characterized by abrupt shifts in attitudes, inconsistencies in responding to simultaneous and intense challenges, and the ambiguity in strategic identity and international orientation.

First of all, the foreign policy was transformed into a reactive character. Value-based policies gave way to discourse-based ones, principledness to opportunism and romanticism to post-truthism. The earlier incompatibility with the great powers’ policies turned into an antagonism. Moreover, in the security field, TFP became threat-oriented, while the previously hardened power turned into full-fledged hard power. While activism continued, the earlier hyperactivity acquired a reactive character, and partisan interventionism become unilateral.

Secondly, foreign policy orientation and strategic identity became unclear as to where and how Türkiye positions itself in the world. In particular, the widespread belief that the US played a role in the July 15 coup attempt and the lack of reaction from European allies led to a radical questioning of conventional alliances and defense policy and a search for strategic autonomy. Although Haugom (2019, pp. 216-219) states that this search was not a change in orientation, the earlier distancing from the West turned into anti-Westernism, and though not officially accepted, Türkiye gave up its Western perspective (Oğuzlu, 2020, p. 138). Moreover, this strengthened Eurasianist and “national and indigenous” outlook were united in opposition to the West. Thus, the “axis shift” that was voiced in the AKP-1 started to become a reality in this period.

Thirdly, this period was characterized by intense and serious problems in foreign relations. For example, in relations with the US, Türkiye faced many crises, threats and sanctions in a very short period of time. In 2017, the arrest of Pastor Brunson for espionage led Trump to threaten Türkiye (The Guardian, 2018). In 2019, Trump sent a letter to Erdogan with warnings and threats (The Guardian, 2019), and increased his support for the YPG. In the same year, the US halted the sale of F-16s and removed Türkiye from the F-35 project, and then imposed sanctions under the CAATSA (US Department of State, 2020). Even Turkish citizens faced visa problems (Metz, 2018). In this period, there were several problems with Europe such as refugees, human rights violations, sanctions against Russia, Finland and Sweden’s NATO membership, and the denial of visas to Turkish citizens. Moreover, Türkiye became the second country to be subjected to an “Infringement Procedure” by the ECHR, when it did not recognize the Kavala judgment (BBC, 2021). Subsequently, the Court ruled “violation” for failure to abide by its final judgment of Türkiye (ECHR, 2022). While these crises were taking place with the West, relations with countries in the region were also problematic. For example relations with Syria, Egypt and the UAE were severed, and relations with Israel, Greece, Saudi Arabia, Iran and Iraq also cooled. Türkiye’s exclusion by other actors was evident in events such as the establishment of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum in 2020, the signing of the Abraham Accords with Israel, and the agreement on the “India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor” project in New Delhi in 2023. Thus, Türkiye faced a geopolitical siege.

Ultimately, all these point to multifaceted inconsistencies and uncertainties in TFP. As a member of NATO seeking alternatives, friendly with Russia but on opposite fronts, an odd candidate for EU membership, Türkiye’s policies were confusing. Political orientations are at odds with economic ones. Therefore, despite an active foreign policy, cooperation and conflict, friendship and enmity were all intertwined and foreign policy was unpredictable, where anything could happen at any moment, and where things could get better in an instant, or worse.

Finally, in terms of its international image, Türkiye became an actor whose position and axis were constantly changing, lacking its appeal and prestige. Nevertheless, with the relatively/fragile strategic autonomy it gained due to its opportunistic attitude, its increasing hard power and its successful initiatives, it remained an actor that could not be neglected by either the great powers or regional actors. The effects and consequences of the change in the LFP during this period are summarized in Table 8.

States seek to conduct their foreign policies within a certain logic. For an effective and stable foreign policy, this logic must be realistic, consistent, sustainable, and its elements should be aligned with each other. The AKP government made an attempt to reform the conformist understanding that had dominated TFP from 1938 to the 1990s. Although this attempt, in the AKP-1 period, involved some risks due to the prioritization of values and discourses, it provided momentum and influence to TFP, as the requirements of the base LFP were largely met. In 2011, with the change in regional conditions, this reform effort took on an increasingly revisionist character on the basis of values and discourses, and this understanding was maintained in a principled manner. However, since this attitude could not be backed by power and was not in line with the international environment, TFP fluctuated and gained a very different outlook at the end of the period. By 2016, with the change in domestic conditions, TFP began to rely on a radical understanding accompanied by reactive discourses and actions involving paradigmatic shifts. However, this approach brought serious problems and contradictions for TFP, which was already destabilized and could not be backed by power. Eventually, Türkiye’s strategic identity and orientation became increasingly blurred due to these problems and contradictions.

The main reason for this strategic volatility under the same government rule is that TFP gradually deviated from the base LFP that ensures strategic stability. Values and discourses played a key role in this deviation.

As seen in this study, values and discourses have always taken precedence over other elements (power-interest-actions) in foreign policy in line with the AKP’s ideological identity. However, while the values and discourses were relatively in alignment with other elements in the AKP-1 period due to a quest for legitimacy and EU vision, this alignment was disrupted in favor of values and discourses in AKP-2 period due to Türkiye’s increasing influence in the regional and international arena, and eventually discourse dominated foreign policy in AKP-3 period along with the relative decline, regime change and distrust towards the West. However, there is a fundamental contrast between the nature of values and discourses and that of foreign policy. Foreign policy is fundamentally shaped by power and the international environment. While power is a controllable element, the international environment is not. The nature of foreign policy, as it is designed domestically but implemented in an uncontrollable domain, requires caution as well as flexibility. Values, on the other hand, have a character that forces one to act independently of the circumstances, while discourses -especially if they are populist in nature- can easily lead to a departure from reality. Therefore, values and discourses (especially rhetoric) always have the potential to drive foreign policy away from reality and consistency. It is crucial, therefore, that they are not an independent multiplier in foreign policy, but rather serve as elements aligned with the others. Otherwise, it may disrupt the base LFP and cause unwanted erratic volatilities, as happened in the first two decades of AKP rule.

In the AKP-1 period, although values were prominent, they remained aligned with other elements and international conditions. However, in the AKP-2 period excessive adherence to values made it difficult to pursue foreign policy in line with power, strategic interests and international conditions. In the AKP-3 period, the problems were much more complicated. This time, values lost their real function and became merely part of the discourse, causing foreign policy to lose its direction. The reaction to the West completely detached discourse from reality and action from principle. Although creating the impression that everything was strategically planned and directing public perception through populist discourses eliminated public pressure, it did not solve foreign policy’s problems. Thus, TFP constructed around post-truth and populist discourses became contradictory and faced serious dilemmas. Contrary to its intended purpose, TFP generated new threats to the country’s security, prosperity and prestige. Hard power alone proved insufficient to address these challenges.

Ultimately, it was not possible to sustain TFP through reactive discourses and opportunistic, force-based actions. Given that foreign policy is the art of achieving maximum benefit at the least cost, a change in TFP was inevitable. Following the 2023 general elections, a new period appears to have begun in which TFP is conducted in line with the base logic. Only through such a shift can Türkiye recoup accumulated costs, normalize its relations with the world, and attain the strategic autonomy it has pursued over the past two decades.

Notes

[1] Following the 2023 general elections, a new period appears to have emerged; however, since this period has only recently begun, it is excluded from the scope of the analysis.

References

Aras, B. (2019). The crisis and change in Turkish foreign policy after July 15. Alternatives, 44(1), 6–18.

Askerov, A. (2017). Turkey’s “zero problems with neighbors” policy: Was it realistic? Contemporary Review of the Middle East, 4(2), 149–167.

Ayata, B. (2015). Turkish foreign policy in a changing Arab world: Rise and fall of a regional actor? Journal of European Integration, 37(1), 95–112.

Aydın Çakır, A., & Arıkan Akdağ, G. (2017). An empirical analysis of the change of Turkish foreign policy under the AKP government. Turkish Studies, 18(2), 334–357.

Aydın-Düzgit, S., & Rumelili, B. (2019). Discourse analysis: Strengths and shortcomings. All Azimuth, 8(2), 285–305.

Babacan, A. (2008). Büyükelçiler Konferansı açış konuşması. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/disisleri-bakani- ali-babacan_in-buyukelciler-konferansi-acis- konusmasi.tr.mfa

Balta, E. (2020). AKP’nin popülist dış politikası. İstanbul Politikalar Merkezi. https://istanpol.org/ Uploads/ContentManagementFile/akpnin-populist-dis-politikasi-- prof-dr-evren-balta.pdf

Balta, E., Kaltwasser, C. R., & Yağcı, A. H. (2021). Populist attitudes and conspiratorial thinking. Party Politics, 28(4), 1–13.

Balta, E. (2023). Türk dış politikasında 2023. https://www.perspektif.online/turk-dis-politikasinda-2023/

BBC. (2014). Turkey loses out on UN Security Council seat. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-29654003

BBC. (2021). Osman Kavala: Avrupa Konseyi’nin Türkiye için başlattığı “ihlal prosedürü” nasıl işleyecek? https://www.bbc.com/turkce/haberler-turkiye-59518748

Çandar, C. (2010). Türk dış politikasında “eksen” tartışmaları: Çok kutuplu dünya için yeni bir vizyon. SETA Analiz, (16).

Çandar, C. (2013). Türkiye’nin değerli yalnızlığı ya da etkisiz dış politika. Radikal.

Çavuşoğlu, M. (2017). 9. Büyükelçiler toplantısı açılış konuşması. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/disisleri- bakani-sayin-mevlut-cavusoglu_nun-ix_-buyukelciler- konferansi-acilisinda-yaptigi-konusma_-9- ocak-2017_-ankara.tr.mfa

Çavuşoğlu, M. (2018). 10. Büyükelçiler toplantısı açılış konuşması. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/data/%20BAKAN/sayin-bakanimizin-acilis-konusmasi-bkon.pdf

Çavuşoğlu, M. (2019). 11. Büyükelçiler toplantısı açılış konuşması. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/site_ media/html/bkon/XI-BKON-sn-mevlut-cavusoglu-acilis- konusmasi.pdf

Çelik, A. H. (2016). Türk dış politikasının niteliği üzerine kavramsal bir tartışma: Değerli yalnızlık mı, şuurlu dinamizm mi? Düzce Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 5(2), 67– 89.

Davutoğlu, A. (1997). Medeniyetlerin ben-idraki. Divan, 3(1), 1–53.

Davutoğlu, A. (2001). Stratejik derinlik: Türkiye’nin uluslararası konumu. İstanbul: Küre Yayınları. Davutoğlu, A. (2008). Turkey’s foreign policy vision: An assessment of 2007. Insight Turkey, 10(1),

79–84.

Davutoğlu, A. (2011a). 3. Büyükelçiler konferansı açılış konuşması. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/ disisleri-bakani-sayin-ahmet-davutoglu_nun-3_-buyukelciler- konferansi_nin-acilisinda-yaptigi- konusma_-03-ocak-2011.tr.mfa

Davutoğlu, A. (2011b). 4. Büyükelçiler konferansı açılış konuşması. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/dorduncu- buyukelciler-konferansi_acilis-konusmalari.tr.mfa

Davutoğlu, A. (2012a). Principles of Turkish foreign policy and regional political structuring. Turkey Policy Brief Series. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/site_media/html/bakanmakale_tepev.pdf

Davutoğlu, A. (2012b). TBMM Plan ve Bütçe Komisyonu konuşması. http://www.mfa.gov.tr/disisleri- bakani-davutoglu_nun-tbmm-plan-ve-butce-komisyonunda.tr.mfa

Davutoğlu, A. (2013). V. Büyükelçiler konferansında yaptığı konuşma. http://www.mfa.gov.tr

Demirtaş Bagdonas, Ö. (2012). A shift of axis in Turkish foreign policy or a marketing strategy? Turkey’s uses of its “uniqueness” vis-à-vis the West/Europe. Turkish Journal of Politics, 3(2), 111–132.

ECHR. (2022). Kavala v. Türkiye [GC], No. 28749/18. https://hudoc.echr.coe.int

Erdoğan, R. T. (2022). “Türkiye Yüzyılı” tanıtım toplantısı konuşması. https://www.tccb.gov.tr/assets/ dosya/2022-10-28-Türkiye_yuzyil.pdf

Ersoy, E. (2009). Old principles, new practices: Explaining the AKP foreign policy. Turkish Policy Quarterly, 8(4), 115–127.

Erşen, E. (2013). Türk dış politikasında Avrasya yönelimi ve Şanghay İşbirliği Örgütü. Ortadoğu Analiz, 5(52), 14–23.

Fisher Onar, N. (2009). Neo-Ottomanism, historical legacies and Turkish foreign policy (Discussion Paper No. 3). EDAM.