Wiebke Wemheuer-Vogelaar

Freie Universität Berlin

Peter Marcus Kristensen

University of Copenhagen

Mathis Lohaus

Freie Universität Berlin

Several studies have pointed to an unproductive ‘division of labor’ in the International Relations discipline (IR), notably its publication patterns, in which scholars based in a ‘core’ publish theory-building work while scholars based in a ‘periphery’ publish mainly empirical, area-oriented, or theory-testing work. The latter would thus mainly act as ‘local informants’ feeding empirical material on ‘their own’ country or region into the theorizing efforts of the ‘core’. We investigate this argument empirically using the dataset compiled by the Global Pathways (GP) project that studies the content in both ‘core’- and ‘periphery’-based and edited journals. Overall, our findings corroborate the argument about a core-periphery division of labor. Our main findings are threefold: (1) In terms of theory, we find that ‘core’ journals publish a larger proportion of theory-developing (and statistical) work and a lower proportion of analytical case studies and descriptive work than do ‘periphery’ journals. Scholars based in the ‘periphery’ are rarely published in these more theoretical ‘core’ journals (accounting for just 5.5% of articles in the journals studied here), but the published articles tend to apply theory. The main division of labor is thus not playing out within ‘core’ journals, but across the ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ worlds of publishing. In the ‘periphery’ journals, we actually find that scholars tend to publish a significant proportion of work using theory. (2) In terms of regional focus, we find that all journals and authors tend to have an empirical ‘home bias’, i.e. focus their empirical work on the region in which they are based, but that this is stronger for ‘periphery’-based journals and authors. This provides some confirmation of an unproductive division of labor where ‘core’ authors publish works about all regions of the globe, while 'periphery' authors have a stronger regional orientation. (3) Finally, we find evidence that some journals and authors – particularly those based in Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia – tend to be more policy-oriented, but we find no conclusive evidence of a core-periphery gap in this context.

1. Introduction

It is a disciplinary truism that International Relations (IR) is not a very international, but rather an Anglo-American or Western-centric discipline.[1] However, recent years have witnessed an attempt to open the discipline and its institutions to a broader range of voices and approaches from outside its Anglo-European ‘core’, what has variously been called “Third World” IR,[2] “non-Western” IR,[3] “peripheral” IR[4] or “global” IR[5], “geocultural pluralism”[6] and the like. This has led to an increasing awareness of the representational politics of IR, as seen in attempts to broaden the cultural representation within major journals. Representational politics of IR matter, even if they are sometimes excessively focused on problematic “Western/non-Western”, “core/periphery”, and “North/South” binaries.[7] Yet the problem is broader than merely increasing the presence of scholarship from the ‘periphery’, ‘Global South’ or ‘beyond the West’ in research publications, textbooks, conferences and so on.[8] To develop effective representational policies in the discipline, it is also important to interrogate what is published where and by whom.

Several studies have pointed to the existence of an unproductive “intellectual division of labor” in which Anglo-European-based or ‘core’ scholars produce theory-building work while scholars from the 'periphery' consume, apply, and test theory.[9] Arlene Tickner (2013:631), for example, describes a “neo-imperialist” division of labor, where the “first world/North” is viewed as the primary producer of “finished goods” such as scientific theories while the “third world/South” is viewed as a source of “raw data” or, at best, “local expertise”. In this hierarchical system, the scholar from the Global South or ‘periphery’ can function mainly as “regional experts” feeding empirical and area-oriented material on their country or region into the ‘core’.[10] They act as “subcontractors to a (usually Western) theory-producing core.”[11] Put in the terms of colonial political economy, Global South scholars are viewed not as “scholars or theorists in their own right” but as “native informants”[12] fulfilling the role of “servants” in the House of IR.[13]

Global circulation networks, in turn, transport this raw “data” to the “North” (or “upstairs” in Agathangelou and Ling’s metaphor)[14] for interpretation and theory-building, repackage it into recognizable “theory” and circulate it for global consumption.[15] Once again, these “advanced theoretical goods” are uni-directionally disseminated into the ‘periphery’.[16] This “intellectual division of labor is anchored in the global imperial order”, Manuela Picq argues, where the Eurocentric ‘core’ retains its status as the global center of theory production while dismissing scholarship from the South as merely “case studies, not theory” and thus not “real IR.”[17] But it is also hegemonic and self-reproducing in that 'peripheral' fields dissuade theoretical work and valorize practical applied knowledge of use to policymakers,[18] thus “perpetuating their own marginalization.”[19]

This paper sets out to study the ‘division of labor’ argument empirically. We aim to test three dimensions of the division of labor argument: (1) that theory production and use is concentrated in a geographical ‘core’; (2) that communities of IR located in a ‘periphery’ tend to publish work that is empirically focused mostly on their ‘own’ region; (3) that knowledge production in this ‘periphery’ is more policy- and practice-oriented than is the case in the ‘core’. Methodologically, we try to test these claims bibliometrically, i.e. by studying the content of IR journal publications, as several studies in the sociology of IR have done before us. Unlike the majority of previous studies of IR, however, we not only examine publications by periphery-based scholars in ‘core’ journals,[20] but use the dataset compiled by the Global Pathways (GP) project to study the content of articles published in both ‘core’- and ‘periphery’-based and edited journals. By looking at both ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ journals, we are able to study whether there is a systematic division of labor in that scholars based in regions of the ‘periphery’ tend to publish work of a different nature (e.g. more empirical and less theoretical work, more on their ‘own’ region/area than on others, more policy-oriented) compared to scholars working in the regions of the ‘core’ publishing in ‘core’ journals – a key part of the division of labor argument. But more importantly, the Global Pathways data enables us to also examine if the publication patterns differ markedly when scholars from the ‘periphery’ or the ‘core’ publish in journals controlled and edited in the ‘periphery’. If we find that scholars based in the ‘periphery’ actually publish more on theory and more on extra-regional and global issues in 'periphery' journals, then this provides evidence that their absence or the particular division of labor in ‘core’ journals may have less to do with what scholars in the ‘periphery’ work on and more to do with who can publish what where, and who is accepted as a producer of such IR and who is not.

Our main findings are (1) in terms of theory, ‘core’ journals publish a larger proportion of theory developing (and statistical) work than do ‘periphery’ journals, and a lower proportion of analytical case studies and descriptive work. Scholars based in the ‘periphery’ are rarely published in these more theoretical ‘core’ journals (accounting for just 5.5% of articles in the journals studied here). The main division of labor is thus not playing out within ‘core’ journals, but across the ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ worlds of publishing. As we turn to the ‘periphery’ journals, we actually find that scholars based in the ‘periphery’ tend to publish a significant proportion of work using theory, even if this work is rarely published in ‘core’ journals. (2) In terms of regional focus, we find evidence that all journals and authors tend to have an empirical ‘home bias’, i.e. focus their empirical work on the region in which they are based, but that this tendency is stronger for ‘periphery’-based journals and authors. This provides some confirmation of an unproductive division of labor in which ‘core’ authors publish work about all regions of the globe, while 'periphery' authors have a stronger regional orientation. However, this comes with the important variation that local-language ‘periphery’ journals are more inclined to publish work with a global focus or on regions other than where the journal is based, while English-language ‘periphery’ journals tend to focus on the regions in which they are based. (3) Finally, in terms of relative policy orientation, we find evidence that some journals and authors – particularly those based in Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia – tend to be more policy-oriented, but no conclusive evidence of a core-periphery gap is found here.

The paper proceeds first by outlining its methodology and the Global Pathways dataset. Second, we present our empirical findings with an emphasis on, firstly, theory use; secondly, regional focus; and thirdly, policy relevance.

2. Methodology and Data

The sociology of global IR has employed different methods for studying the social structure of the discipline, including studies of textbooks and syllabi[21] or surveys among IR scholars.[22] This article adds to the part of the literature that emphasizes bibliometric studies of journal publications, which are often considered as providing the “most direct measure of the discipline itself.[23] In contrast to surveys among scholars and investigations into how the discipline is being taught, journal publications indicate what counts as ‘real’ IR research and what gets circulated in the wider disciplinary network.[24] That is why journals provide a useful entry point for examining arguments about a division of labor in global IR research.

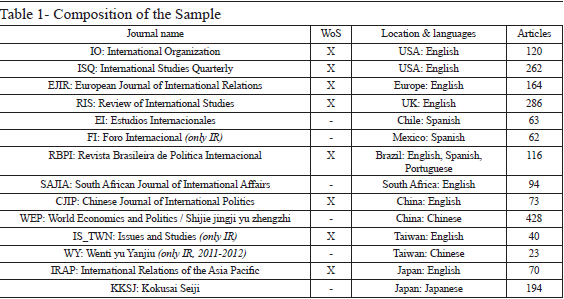

Much of the literature on the contents of IR research tends to study North American and European journals indexed by the Web of Science. Drawing on the Global Pathways dataset, we are able to cast a wider net, which allows us to examine the ‘division of labor’ thesis. To represent the ‘transatlantic core’, we study International Organization (IO), International Studies Quarterly (ISQ), European Journal of International (EJIR), and Review of International Studies (RIS). These four journals are based on both sides of the Northern Atlantic, are highly regarded according to the TRIP survey, and receive many citations in the Web of Science.[25] In addition, our sample includes ten ‘periphery’ journals based in Latin America, Africa, and Asia, both within and outside of the Web of Science. These were selected to provide information on a diverse set of IR communities from different world regions, including comparisons between English and local-language outlets of the same region, when possible. Taking into account some exclusions due to data and methodological concerns (see below), the sample covers 1,995 IR research articles published between 2011 and 2015.

For each article in these journals, the authors’ institutional affiliation at the time of publication has been coded based on the information indicated directly in the journal articles, or in some cases in each (print) issue. This allows us to assign a regional base to each author. In addition to geographical base, we also investigated where authors obtained their PhD degrees. This required extensive research on authors’ biographies via departmental websites, professional social networks, and general web search. Both pieces of information point to specific institutions and countries, but for the sake of simplicity the results were aggregated at the level of world regions.

The existing literature on global inequalities in IR tends to operate with meta-geographical terms like ‘core’ versus ‘periphery’, ‘West’ versus ‘non-West’, and ‘North’ versus ‘South’. Such terms can surely be useful, and sometimes unavoidable, heuristic devices when describing the structural inequalities in the discipline. However, aggregating can also be seen as problematic and over-simplistic. This becomes most evident when categories are applied to the scholarly communities of entire regions or collections of regions, which are often not uniformly ‘peripheral’ or ‘core’.[26] Even for specific journals, it is never clear-cut. There might be good justifications for considering International Organization, for instance, as a ‘core’ journal, but do International Relations of the Asia-Pacific or Chinese Journal of International Politics count as ‘periphery’ journals when they have senior U.S. and European academics on the editorial board and are published by Oxford University Press?

The same problem applies to the identification of author affiliation. Rather than focus on the crude categories of ‘core’ and ‘periphery’, we prefer to operate with nine geographical regions. Given the dominance of the Anglophone world in the journals we examine, and the wider discipline, we operate with distinct categories for North America, Australia and New Zealand, and the United Kingdom – what has sometimes been called the “Anglo-American condominium”.[27] Together with Continental Europe, these regions are often considered the ‘transatlantic core’ of IR. In addition to this, we distinguish Latin America and the Caribbean, East Asia, South and Southeast Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and Sub-Saharan Africa. We acknowledge that these regional classifications are not unproblematic either, but they provide a more nuanced disaggregation than the more meta-geographical terms ‘core’ and ‘periphery’. It is also important to note that this classification is purely based on the authors’ geographical location and is not a study of their ethnicity or nationality. Therefore, scholars based in the ‘core’ may very well be nationals of a country associated with the ‘periphery’, and vice versa.

Co-authorship composition across regions is highly interesting in the context of a potential global ‘division of labor’. As several observers have noted, co-authorships can be part and parcel of the unequal global division of labor as exemplified by the case of papers “co-authored by a Western and a non-Western IR-scholar, where the latter provides ‘local empirical data’ to be used in the testing of allegedly universal theories possessed by the former.”[28] Even if labor in co-authored papers were not actually divided this way but the co-authorship were, say, a strategic choice for 'periphery' scholars to get published, as the interviews conducted by Aydinli and Mathews suggest, co-authorships may nonetheless translate into an imbalanced division of prestige where the 'core' scholar bolsters theoretical prestige backed by the legitimacy of regional expertise, while the 'periphery' scholar is not recognized for theoretical expertise.[29]

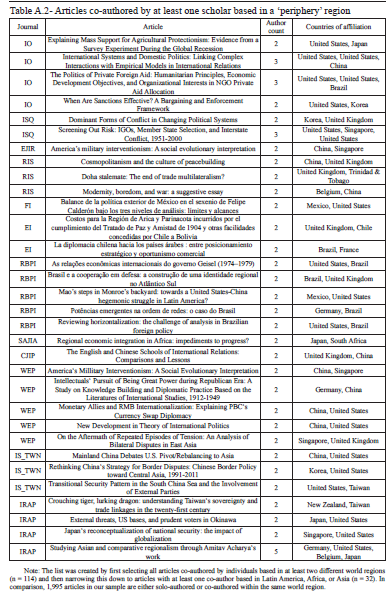

While these kinds of co-authorships are conceptually interesting, they are exceedingly rare.[30] In the overall ‘Global Pathways’ dataset, 28 percent of articles are co-authored; yet most of these authors are based within the ‘transatlantic core’.[31] Between 2011 and 2015, the 14 journals we analyze here published just 32 articles (1.5 percent) co-authored by at least one person based in a ‘periphery’ region. We refrain from analyzing these pieces quantitatively but include a list in the appendix. This omission seems unfortunate given our research interest, but it decreases the likelihood of bias in our findings. Moreover, including these few cross-regional co-authorships would also have complicated our analysis to a significant degree, as we could only guess which author was responsible for which parts of the research. To infer that 'periphery' scholars contributed empirical data while core-based scholars contributed the theory would only reinforce the very structure we seek to interrogate.

Apart from geographical meta-data, we have coded the content of articles using a detailed codebook with multiple-choice variables. Each article was assessed by at least one research assistant, who classified the contents by searching for keywords and patterns in the whole article. These choices were then reviewed by senior coders (also referred to as arbitrators) to check for consistency. The Global Pathways codebook and coding strategy is based on that developed by the TRIP project for their original journal analysis.[32] Since their focus was not explicitly on the study of ‘global IR’, the TRIP codebook has been adapted to this purpose by the GP team. In this context, several new variables were introduced and values for existing variables were altered or added. The categories of interest for this article are: the usage of theory, the empirical focus in terms of geography, the overall level of abstraction and generalizability, and the inclusion of policy advice. The full dataset, list of variables, and codebook are available via the project’s website.[33]

3. Empirical Findings

3.1. Theory and approach

Theory has historically assumed a central role in the social and intellectual structure of International Relations. Theory is therefore also central in the literature about core-periphery structures and a ‘division of labor’, the argument being that the ‘core’ retains a near-monopoly on theorizing (despite recent anxieties about the “End of IR theory”).[34] Coding for ‘theory’ in journal publications raises a more fundamental question about what ‘counts’ as theory, different concepts of theory, the boundary work involved in distinguishing ‘proper theory’ from work that is ‘atheoretical’, ‘empirical’, ‘descriptive’, ‘practical’ and so on. These delineations are a key part of the ‘core-periphery’ structures themselves, for instance when certain types of work are described as atheoretical and thus allegedly of lesser value. Furthermore, there is a real risk of implicitly applying ‘Western’ or ‘core’ concepts of theory as the only recognizable or detectable kind of ‘theory’.[35] In that case, we would risk finding only what we are looking for, namely the dominance of said theories.

There is no easy solution to avoid biases when it comes to theory, but to be as open as possible, we track theoretical approaches based on the labels and keywords used by the authors themselves. Such self-identification takes place whenever an author names a theoretical approach or makes use of characteristic keywords. This includes articles employing a theory to frame the article’s question and answer, those analyzing theories themselves as their main object, as well as articles using theories as sources for competing explanations. The coding includes mainstream ‘Western’ IR theories, for which we identified indicators in our codebook, such as “balance of power” for realism. Additionally, we recorded references to theoretical concepts from bordering disciplines, for example when authors directly draw on sociology or economics. We also trace what has been called ‘indigenous’, ‘localized’, ‘non-Western’, or ‘Global IR’ theories, which were coded based on geographical or cultural markers such as “Chinese exceptionalism” or “The Kyoto School.” This open-ended coding thus tracks whether articles are using any kind of theory, irrespective of whether it is rooted in paradigmatic IR, imported from somewhere else, or combinations thereof.

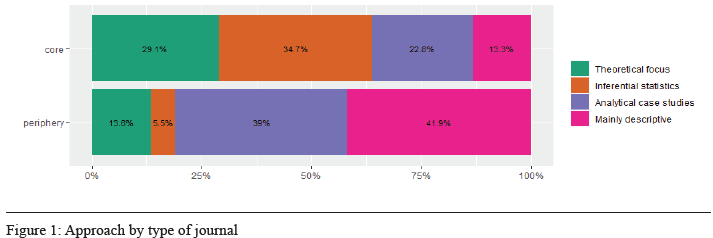

A second piece of information is assessed independent of theory usage but closely linked to it: for each article, we assess their overall approach. Our coding scheme distinguishes four potential outcomes. The most abstract type of article is primarily focused on theory development, either in the format of a purely theoretical essay or by pairing theoretical elaborations with a short empirical illustration. Another typical kind of article uses formalized techniques of ‘inferential statistics’, such as regression analysis (at times also in conjunction with short case-study vignettes). The third type of article is labelled ‘analytical case studies’ and contains different approaches such as process tracing, comparative case studies, or narrative case studies; the common denominator here is the goal of (also) engaging in causal analysis. This separates it from the fourth type of article – ‘mainly descriptive’ research, which can be of a qualitative or quantitative nature but does not involve systematic causal explanation.

Figure 1 contains our findings for the overall approach of articles. A clear difference between the two sets of journals concerns the relative emphasis on theory compared to empirics. Almost a third of the articles from ‘core’ journals have a predominantly theoretical focus, whereas this proportion is only 13.6% in ‘periphery’ journals. Among the remainder of articles with an empirical focus, ‘core’ journals often publish work using inferential statistics (34.7%, and this mainly in ISQ and IO) followed by analytical case studies and, lastly, mainly descriptive work. Meanwhile, inferential statistics are almost absent in ‘periphery’ journals. By contrast, analytical case studies and mainly descriptive are by far the most prominent general approaches.

Overall, this confirms the division of labor argument in that ‘core’ journals are much more likely to publish theory-developing work. This suggests that the bulk of theory production takes place in these journals, while the ‘periphery’ journals are much more likely to publish descriptive articles with or without references to theory.[36] However, we do find that 13.6% of articles in ‘periphery’ journals have a theoretical focus, and, more importantly, that approximately 90% of their authors are also based in periphery regions, with more than half of these holding a PhD from a university located in the periphery. Of the 29.1% pure theory articles in the ‘core’ journals, however, 95% have authors located in the ‘core’ and most of the remaining authors hold a PhD from the ‘core’.

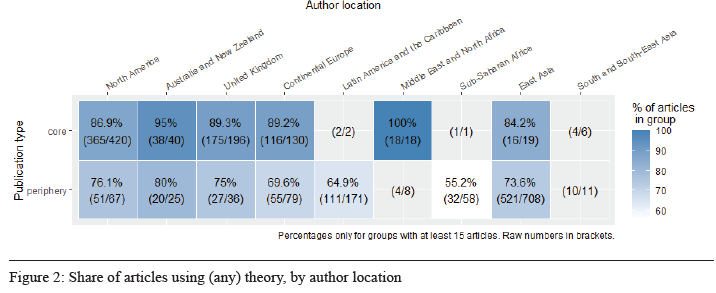

However, when we move from theory development to the use of theory, we find a somewhat more mixed picture. The share of articles using theory is still larger for authors based in North America, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand, and Continental Europe compared to authors based in Latin America and the Caribbean, East Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. More specifically, scholars based in regions typically conceived as ‘core’ – North America, UK, Australia and New Zealand, and Continental Europe – publish theory-informed work in both ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ journals. Authors based in these four regions tend to publish predominantly theory-informed articles, but even more so when publishing in ‘core’ journals (around 90%). The proportion of articles with some use of theory is lower for all four regions when they publish in ‘periphery’ journals, but still above 70%.

As we turn to the regions typically conceived as ‘periphery’, it is worth noting that there is an asymmetry in the dataset. Our sample does not contain journals based in the Middle East and North Africa, South and Southeast Asia, or Australia and New Zealand (although EJIR had Australia-based editors). Scholars based in these regions will therefore only appear in our sample if they publish outside their home region, which explains their relative scarcity. Moreover, scholars based in regions with a ‘periphery’ journal often only publish in that journal, and not in other ‘periphery’ journals. Authors based in East Asia, for example, rarely publish in ‘core’ journals, and even less so in ‘periphery’ journals based in other world.[37] This pattern of limited ‘periphery-periphery’ exchange confirms that most interactions happen through the ‘core’ regions.[38]

As we turn to the regions typically conceived as ‘periphery’, it is worth noting that there is an asymmetry in the dataset. Our sample does not contain journals based in the Middle East and North Africa, South and Southeast Asia, or Australia and New Zealand (although EJIR had Australia-based editors). Scholars based in these regions will therefore only appear in our sample if they publish outside their home region, which explains their relative scarcity. Moreover, scholars based in regions with a ‘periphery’ journal often only publish in that journal, and not in other ‘periphery’ journals. Authors based in East Asia, for example, rarely publish in ‘core’ journals, and even less so in ‘periphery’ journals based in other world.[37] This pattern of limited ‘periphery-periphery’ exchange confirms that most interactions happen through the ‘core’ regions.[38]

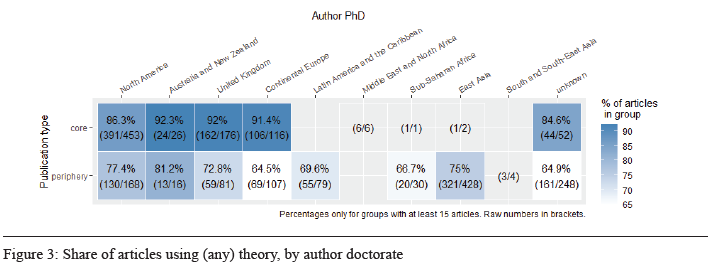

The pattern is also striking when we consider the authors’ educational background (Figure 3). Authors with doctorates from North America, UK, Australia and New Zealand, or Continental Europe have published theoretical work in both ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ journals, although they publish a higher proportion of theory-using work in the former. Authors with doctorates from other regions, by contrast, hardly publish in ‘core’ journals at all. Just nine articles there were authored by individuals with an Asian, African, or Middle Eastern PhD (six of which have Israeli doctorates). While we lack data on some authorship records (‘unknown’ in Figure 3), it seems unlikely that those would change the pattern entirely.[39]

Thus, authors based outside the ‘core’ publish theory-informed work, but they do so largely in ‘periphery’ journals. These ‘core-periphery’ structures become even stronger when we consider location of doctoral training instead of current institutional affiliation. Authors holding PhDs from ‘core’ regions have markedly more freedom of choice, indeed can publish anywhere, while authors with PhDs from ‘periphery’ regions can only publish in ‘periphery’ journals. This data furthermore illustrates that the search for what some have called ‘homegrown theorizing’ from the periphery[40] – if defined broadly as theory-informed work produced by scholars trained in the periphery – still has very low chances of being published in ‘core’ journals. But it thrives in ‘periphery’ journals. This, again, underlines the importance of establishing and maintaining ‘periphery’ journals like All Azimuth for a more global IR.

3.2. Empirical focus

The diverging empirical foci of 'core' and 'periphery' IR have also been discussed in the literature on the unequal patterns of publication in the discipline. One of the main critiques has been that scholars in the ‘periphery’ or ‘Global South’ are put into a problematic position as sources of primary empirical material about ‘their own’ country or region, rather than as subjects of theorizing about international relations more generally. That is, in the term employed by Gayatri Spivak and several observers in IR, a position of ‘native’ or ‘local’ informants.[41] The division of labor, Tickner argues, results in a situation where much “peripheral scholarship tends to description of local or regional events and problems instead of conceptualization of the world, serving at best as ‘raw materials’ for the grand narrative constructed by theorists of the core.”[42] Like area studies, Tickner contends, peripheral IR engages mainly in empirical description that answers to the ‘local’ rather than the ‘universal’.

We study this argument by coding the ‘region(s) under study’ for each article. This multiple-choice variable captures for which geographical locations the articles discuss empirical evidence. If an article addressed German-Japanese relations, for instance, this would be counted for both Western Europe and East Asia. Studies addressing countries spread across all world regions without any particular emphasis, for example analyzing the statistical effects of IMF lending, are coded as global. This allows us to study the ‘local informant’ argument, and the extent to which journals tend to publish works mainly about their ‘own’ region. To provide a fine-grained picture, we distinguish twelve regional markers: Western and Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, North America, Latin America and the Caribbean, Sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and North Africa, East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Oceania, Global, and ‘None’ in case of purely theoretical or abstract articles.

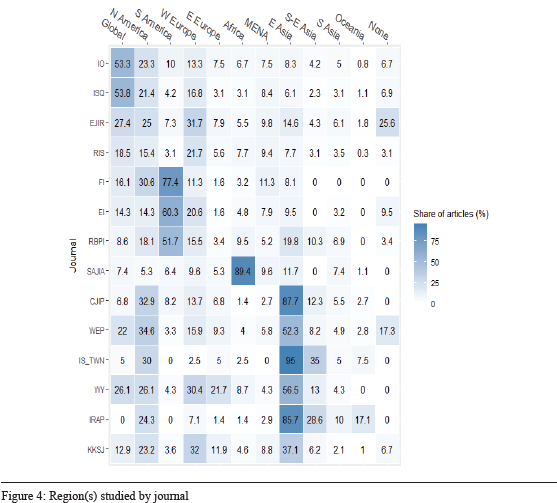

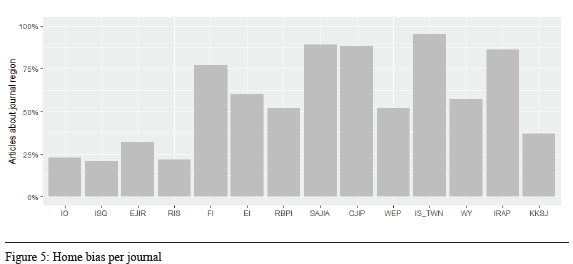

We find that most journals tend to have a ‘home bias’ towards studying the region in which the journal is based. Yet, as figure 4 and especially figure 5 illustrate, this home bias is relatively weaker for ‘core’ journals. Articles operating at the ‘global level’ are also more present in IO and ISQ while purely abstract articles (region ‘none’) are more present in EJIR. Conversely, the ‘home bias’ is high in several 'periphery' journals. 85 to 95 percent of articles in the South African Journal of International Affairs (South Africa), the Chinese Journal of International Politics (China), Issues and Studies (Taiwan) and International Relations of the Asia-Pacific (Japan) study the journals’ own region.

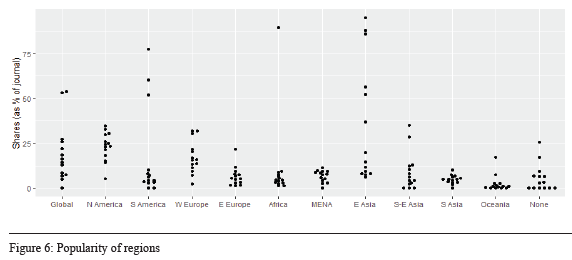

Note that SAJIA, CJIP, IS, and IRAP are all English-language 'periphery' journals. The empirical ‘home bias’ is less pronounced in local-language journals like Wenti yu Yanjui [Issues and Studies] in Taiwan, Kokusai seiji [International Politics] in Japan, or Shijie jingji yu zhengzhi [World Economics and Politics] in China. This suggests that Anglophone ‘periphery’ journals serve to debate regional issues with the (Anglophone) world, as the mission statements of journals like CJIP and IRAP suggest. In other words, one might say that these outlets are used to ‘tell the world about their region’. Conversely, local-language journals are used to ‘tell the region/country about the world’. They publish more articles that study other world regions, like Europe and North America, or that adopt a global scope.[43] This brings us to how different regions are covered in our sample of journals (figure 6).

One notable trend here is the fairly even coverage of North America, which is being studied in around 15-35% of articles across all journals (with the exception of SAJIA). Virtually all 'periphery' journals (again, except SAJIA) tend to publish a significant number of articles focused on North America (on average 24% of articles). This rate is greater than even that of the ‘core’ journals’ tendency to study North America. A similar pattern, albeit at lower levels, emerges for Western Europe. But the reverse is not true, as ‘core’ journals predominantly publish articles with a ‘global’ scope or that study North America and Western Europe. For Latin America, Africa, and East Asia, figure 6 shows that they are either popular objects of study – in their ‘own’ journals, indicated by the high values in the graph – or hardly featured at all. Not surprisingly, the least-frequently studied regions are those without their ‘own’ journals in our sample (MENA, South Asia, Oceania).

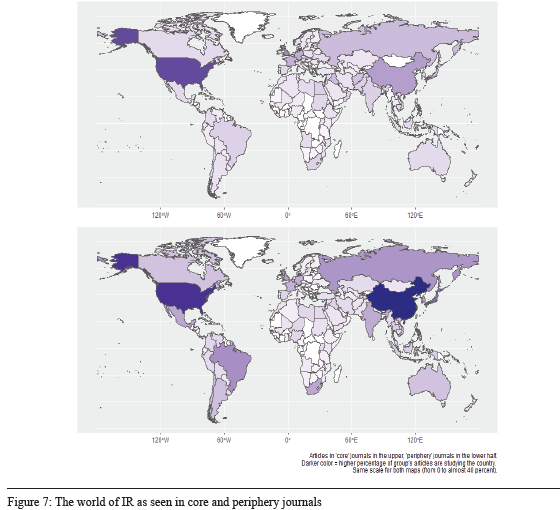

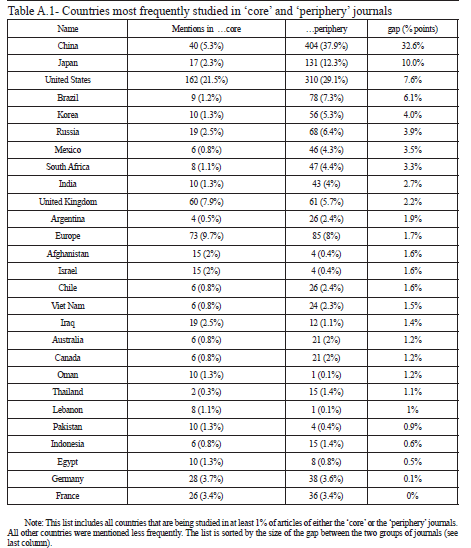

A more granular way to visualize the divergent empirical foci is by contrasting a global map of which countries are covered in ‘core’ journals vis-a-vis the ‘periphery’ journals (figure 7). On the one hand, 'core' journals tend to primarily cover major economies and military powers like the United States (21.5%), secondarily Europe as a whole (9.7%), the United Kingdom (7.9%), Germany (3.7%), France (3.4%) and then China (5.3%), Russia (2.5%) and Japan (2.3%). Apart from that, they tend to have a comparatively higher focus than ‘periphery’ journals on Europe and the United Kingdom and, more notably, specific countries with strong security interests (Afghanistan, Iraq, Israel, Pakistan, Egypt).[44]

The 'periphery' journals, on the other hand, predominantly publish work on China (37.9%), the United States (29.1%), and Japan (12.3%). These results resemble the ‘core’ journals in the attention paid to large economies and influential states, such as members of the UN Security Council (with even more attention on the United States than in ‘core’ journals). In addition, however, the ‘periphery journals’ have different priorities to some extent (see annex, table A-1). They focus much more on their own ‘home’ states (Brazil 7.3%, Japan 12.3%, Mexico 4.3%, Chile 2.4%, South Africa 4.4%), and on neighboring countries (like Argentina 2.4%, Korea 5.3%, Vietnam 2.3%, Thailand 1.4%). This could be seen as an equivalent to the ‘core’ journals’ focus on states that concern their security and foreign policy interests. It is worth noting further that all the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) generally receive more attention in 'periphery' journals. As figure 4 showed, the Brazilian journal RBPI is the journal outside East Asia and Africa with the most articles on those regions.

Taken together, the data on ‘empirical focus’ sheds new light on the division of labor hypothesis: ‘core’ regions are covered by most journals worldwide, whereas ‘periphery’ regions are covered more extensively by journals based in such regions. This largely confirms the argument made by critics of the ‘division of labor’ in IR, namely that work empirically oriented towards ‘core’ regions like North America and Europe is viewed as ‘general IR’, while work on ‘periphery’ regions is viewed as regional or area studies.[45]

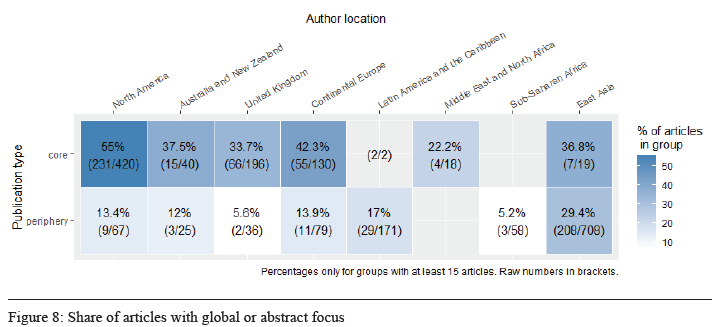

A different way to examine the empirical ‘division of labor’ argument is by looking at the share of articles without any specific regional or country focus. Put differently, this concerns the share of articles with a ‘global’ empirical focus or no such focus at all. This is another way of capturing abstract forms of reasoning that tend to decontextualize, or even devalue context, both of which are likely to occur with the implementation of inferential statistics, formal modeling or theoretical arguments. Figure 9 (‘global or abstract focus’) thus covers both articles with the universalist ambition of providing generalizable empirical findings at the highest possible ‘global’ level (for example via large-n quantitative papers) and/or high levels of abstraction with no empirical or regional focus (typical of theorizing or formal modeling papers).

As the figure shows, authors based in North America and continental Europe tend to publish articles with a ‘global or abstract’ focus almost exclusively in ‘core’ journals and to a much lesser extent in ‘periphery’ journals, where the vast majority of articles are regionally oriented in some way. Scholars based in the 'periphery' tend to publish a lower percentage of ‘global or abstract’ articles both in ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ journals - with the proportion and absolute number highest for scholars based in East Asia.

3.3. Policy prescription

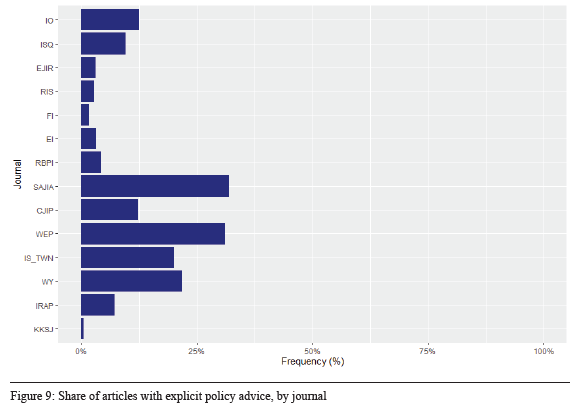

A final dimension of the division of labor argument is that IR in certain, mainly peripheral, regions tends to be more applied or policy-oriented. Practical orientation is partly captured in the above two parts on general approach and empirical focus, but an additional indicator for policy orientation is whether articles contain explicit policy prescriptions (figure 9).

When looking at the journal level, we find that articles in the China-based journal Shijie jingji yu zhengzhi and the South African Journal of International Affairs contain policy prescriptions in around 30% of the articles, followed by the two Taiwan-based journals Issues and Studies and Wenti yu Yanjui. However, the two US-based journals International Organization and International Studies Quarterly also contain policy prescriptions in more than 10% of the articles. The journals least likely to publish articles with policy prescriptions are in fact the Japanese journal Kokusai Seiji, the Chilean Estudios Internacionales, the Mexican Foro Internacional, the Brazil-based Revista Brasileira de Politica Internacional as well as the UK-based Review of International Studies and the European Journal of International Relations. That the journals based in Latin America are among those least likely to include explicit policy prescriptions is surprising considering that the region has been characterized as concerned with “lo práctico” and “practical knowledge susceptible to being translated into policy formulae”.[46] In sum, there is no clear evidence that journals based in the ‘Anglo-European core’ are more or less likely to publish policy-oriented work.

.

.

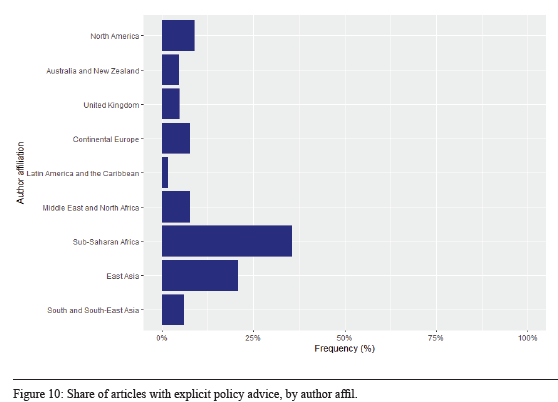

If we turn to the author level, authors based in Sub-saharan Africa (mainly publications in SAJIA) and East Asia also stand out as most inclined to offer explicit policy advice in articles. But apart from these, there is no clear evidence that scholars based in ‘core’ or ‘peripheral’ regions are more likely to provide policy advice in their academic work (see figure 10).

However, policy advice is not per se an indication of a relatively more ‘regional/local’ as opposed to a more ‘global/universal’ focus. Such advice could, in principle, be offered to actors in other regions, international organizations or NGOs. So, in order to connect fully to the division of labor thesis, further research would also have to examine whether the prescriptions are aimed at ‘local’ audiences. Although there is no clear ‘core-periphery’ pattern concerning the share of policy advice, we do find that policy advice tends to be based on very different approaches. In ‘core’ journals, 50.9% of the articles containing policy advice are based on inferential statistics, 20.8% are based on analytical case studies, and 17% on a mainly descriptive approach. In ‘core’ journals, furthermore, articles coded as global in scope or no regional focus are, in fact, more likely to include policy advice than articles with a regional focus. In ‘periphery’ journals, by contrast, most articles containing policy advice are descriptive in approach (56.3%), followed by analytical case studies (32.2%) and very few are based on inferential statistics (3.5%). This pattern is, of course, consistent with the general approaches in those journals (figure 1), but even more outspoken.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

This paper set out to examine the argument about the existence of a ‘division of labor’ in IR along core-periphery lines, with a dominant ‘core’ publishing most of the theoretical work and a dominated 'periphery' publishing empirical, descriptive, and area-specific work. Methodologically, it should be noted that the paper’s findings are based on comparative analysis of an admittedly limited sample of articles published in four ‘core’ and eight ‘periphery’ journals over the course of five years (2011-2015). As we have noted throughout, this has a bearing on the results. We can only encourage further research on a more expansive sample of journals and especially including journals from regions not covered here, such as Eastern Europe, the Middle East, South Asia, or Oceania.

Differences in sample composition also make it difficult to directly compare our findings to earlier comparative analyses of IR scholarship. Some of the journals studied here, such as the Chinese Journal of International Politics, were founded quite recently.[47] On the one hand, the growth in journals likely translates into more room for diversity, both in terms of who publishes and what is being published. This trend is illustrated by the fact that the Web of Science now collaborates with SciELO to incorporate sources (not only) from Latin America and the Caribbean. Even within the predominantly English-language Web of Science, the share of social science articles published by European and East Asian authors has grown between 1980 and 2009 at the expense of North Americans, whose share dropped from 62 to 49 percent.[48] Presumably, the market share of articles authored in the ‘periphery’ is growing even more strongly in journals outside the WoS. On the other hand, a growing chorus of voices does not automatically equal dialogue and engagement. It may well be that IR scholarship as a whole remains insular, as various sub-communities do not engage with each other in meaningful ways. Some of our findings here and elsewhere support this rather pessimistic view.[49] Moreover, the quantity of publications does not directly translate into visibility or impact as measured by citations. Questions about the ‘division of labor’ between different research communities are more pressing than ever. Our findings in this article suggest that ‘core-periphery’ patterns exist within the chosen journals. However, the results also nuance, and in some ways challenge, the simplistic reading of a dominant 'core' and dominated ‘periphery’.

Scholars based in the ‘periphery’ publish a significant proportion of work using theory in ‘periphery’ journals, but these articles rarely make it into ‘core’ journals. This seems to provide evidence that the particular hegemonic constellation has less to do with what scholars in the Global South work on, and is more so a product of gatekeeping on the part of the ‘core’ concerning what constitutes permissible IR (theory). However, it is also possible that self-selection mechanisms are at work. Maybe scholars based in the ‘periphery’ do not submit theoretical work to ‘core’ journals because they anticipate very low chances of acceptance. Submission data including comparative rates of rejection would be necessary for more research in this direction. Moreover, this paper has studied the usage, but not necessarily the production, of theory. It is therefore, in principle, still possible that theory-use basically covers a rehashing of mainstream IR theories produced in the ‘core’, perhaps applied to novel empirical cases, but in essence reproducing a division of labor where the 'core' produces and the 'periphery' consumes theory. Other studies have shown that explicitly “non-Western” theory is quite rare but can be found in East Asian journals; at the same time, many articles both in the ‘core’ and the ‘periphery’ draw on combinations of theories, which may be a sign of eclecticism and/or innovation.[50] Probing this further would require additional fine-grained assessments of how theory is used and developed, which seem difficult to conduct at a larger scale.

In terms of empirical focus, we find that all journals and authors tend to have an empirical ‘home bias’. This is more pronounced in the 'periphery' journals, while authors and journals based in the ‘core’ publish more works with a global or non-regional empirical focus. Overall, the data on empirical focus confirms the existence of an empirical ‘division of labor’ where ‘core’ authors and journals publish more widely about all regions of the globe, while 'periphery' authors have a stronger regional orientation. However, some nuances are worth mentioning. We do not find evidence that scholars based in the ‘periphery’ routinely gain access to ‘core’ journals as ‘informants’ or ‘local experts’ providing insights on their home region. Instead, they hardly publish there at all. More such cases might emerge when taking into account co-authorship between researchers from different world regions; yet, given the rarity of cross-regional collaboration in our sample, the potential impact is limited.

In addition, home bias is universal but differs in degree. In all four ‘core’ journals, the respective home regions are the most frequently studied individual regions; but in contrast to the ‘periphery’ journals, they come in third place after globally oriented and purely abstract research. Lastly, it should be noted that the local-language journals in Latin America and East Asia have home biases around 50%, with Mexican Foro Internacional as an outlier (75%). This is significantly lower than in the Anglophone 'periphery’ journals. Journals addressing the domestic audience, in other words, routinely publish works with a more global or outward-looking focus. At the same time, they retain a strong interest in their home region, which may reflect the authors’ desire to achieve practical policy relevance[51] and/or the goal of studying one’s own region because it is overlooked by the ‘core’ parts of the discipline.

Finally, it is important to emphasize that an empirical ‘division of labor’ – and the home bias in particular – is thus not necessarily and exclusively a product of global core-periphery structures forcing 'periphery' scholars into a rigid role of ‘local experts’. This explanation does not afford much agency to scholars based in the 'periphery', who, after all, also tend to publish regionally oriented works in journals based and controlled in the ‘periphery’. It may also be a response to empirical gaps in the ‘core’ discipline and/or local policy needs. In that regard, ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ are perhaps not really that different, each with their home biases and no clear evidence that one has a clearer policy orientation than the other.

What do our results mean for the wider ‘Global IR’ project and the potential for change in the discipline? Here it is important to be aware of the path dependencies at play. Reputation and prestige are sticky, indeed self-reinforcing, and it is hard to change the existing hierarchy. The role and identity of certain journals as, say, the key outlet to send theoretical work employing social theory such as EJIR is not changed in the short term. At the same time, ‘periphery’ journals that have a ‘policy’ or ‘home bias’ in their mission statement may also tend to attract work from their home region.[52] The wider political economy of publishing must also be taken into account here. Publishers may have a certain interest in maintaining the profile of a journal. Career incentives for authors, e.g. in scholarly communities in which publishing an article in a particular set of journals is crucial to making a career, may also not always favor an opening up of the field.

Therefore, even if some of the more prestigious journals based in the ‘core’ have been launching initiatives to be more accepting toward a wider array of submissions, including in languages other than English, it remains an open question whether this can lead to real change as long as their editorship remains tied to a particular geographical region. Journals that do have a rotating editorship mostly seem to move their bases around the (Northern) Atlantic, if they move across regions at all. There are also other causes to be skeptical of attempts at opening up, be it the journals trying to attract more submissions from outside the ‘core’ or the International Studies Association (ISA) increasingly entering the global conferencing market with ‘regional’ chapters and conferences (while the main event remains in North America). A legitimate question seems to be whether these developments challenge the hegemonic status of American IR or in fact reinforce it. Put differently, is ‘American-IR-turned-Global’ the same as a ‘Global IR’? If the status of the ‘core’ remains intact, it is unclear how much will change by adding some ‘regional’ chapters, especially if these obtain only the status of ‘regional IR’ studying their own regions.

This leads to a wider discussion about the limits of a representational ‘opening up’ of IR. As several recent works have emphasized, the need to address diversity (and core-periphery structures) goes way beyond the representational level.[53] Having more publications in major IR journals authored by scholars based in the Global South would not in itself challenge the wider core-periphery structures of the global discipline.[54] This requires a more fundamental change of what counts as ‘permissible’ and ‘proper’ IR.

ANNEX

Acharya, Amitav. “Global International Relations (IR) and Regional Worlds.” International Studies Quarterly 58 (2014): 647–59.

Acharya, Amitav, and Barry Buzan, eds. The Making of Global International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

———. Non-Western International Relations Theory. Abingdon: Routledge, 2010.

Agathangelou, Anna M., and L. H. M. Ling. “The House of IR: From Family Power Politics to the Poisies of Worldism.” International Studies Review 6, no. 4 (2004): 21–49.

Alejandro, Audrey. “Diversity for and by Whom? Knowledge Production and the Management of Diversity in International Relations.” International Politics Review (2021). doi: 10.1057/s41312-021-00114-0.

———. Western Dominance in International Relations?: The Internationalisation of IR in Brazil and India. London; New York: Routledge, 2018.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Gonca Biltekin. Widening the World of International Relations: Homegrown Theorizing. London: Routledge, 2018.

Aydinli, Ersel, and Julie Mathews. “Are the Core and Periphery Irreconcilable? The Curious World of Publishing in Contemporary International Relations.” International Studies Perspectives 1 (2000): 289–303.

———. “Periphery Theorising for a Truly Internationalised Discipline: Spinning IR Theory Out of Anatolia.” Review of International Studies 34 (2008): 693–712.

Buzan, Barry. “How and How Not to Develop IR Theory: Lessons from Core and Periphery.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 11 (2018): 391–414.

Capan, Zeynep Gulsah. “Decolonising International Relations?” Third World Quarterly 38, no. 1 (2017): 1–15.

Chen, Ching-Chang. “The Absence of Non-Western IR Theory in Asia Reconsidered.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 11 (2011): 1–23.

Crawford, Robert, and Darryl Jarvis. International Relations: Still an American Social Science? Albany: SUNY Press, 2001.

Colgan, Jeff D. “Where Is International Relations Going? Evidence from Graduate Training.” International Studies Quarterly 60, no. 3 (2016): 486–98.

Dunne, Tim, Lene Hansen, and Colin Wight. “The End of International Relations Theory?” European Journal of International Relations 19 (2013): 405–25.

Ergin, Murat, and Aybike Alkan. “Academic Neo-Colonialism in Writing Practices: Geographic Markers in Three Journals from Japan, Turkey and the US.” Geoforum 104 (2019): 259–66.

Eun, Yong-Soo. “Beyond ‘the West/Non-West Divide’ in IR.” Chinese Journal of International Politics 11 (2018): 435–49.

———. “Opening up the Debate over ‘Non-Western’ International Relations’.” Politics 39 (2019): 4–17.

Gelardi, Maiken. “Moving Global IR Forward – A Road Map.” International Studies Review 22, no. 4 (2020): 830–52.

Goldmann, Kjell. “Im Westen Nichts Neues: Seven International Relations Journals in 1972 and 1992.” European Journal of International Relations 1, no. 2 (1995): 245–58.

Hagmann Jonas, and Thomas Biersteker. “Beyond the Published Discipline: Toward a Critical Pedagogy of International Studies.” European Journal of International Relations 20, no. 2 (2014): 291–315.

Hamati-Ataya, Inanna. “IR Theory as International Practice/Agency: A Clinical-Cynical Bourdieusian Perspective.” Millennium 40 (2012): 625–46.

Hellmann, Gunther. “Interpreting International Relations.” International Studies Review 19 (2017): 296–99.

Hendrix, Cullen S., and Jon Vreede. “US Dominance in International Relations and Security Scholarship in Leading Journals.” Journal of Global Security Studies 4, no. 3 (2019): 310–20.

Hoffmann, Stanley. “An American Social Science: International Relations.” Daedalus 106 (1977): 41–60.

Holsti, Kalevi. The Dividing Discipline. Boston: Allen & Unwin, 1985.

Kapoor, Ilan. “Hyper‐self‐reflexive Development? Spivak on Representing the Third World ‘Other’.” Third World Quarterly 25, no. 4 (2004): 627–47.

Koeijer, Valerie de, and Robbie Shilliam. “Forum: International Relations as a Geoculturally Pluralistic Field.” International Politics Reviews (2021). doi: 10.1057/s41312-021-00112-2.

Kristensen, Peter Marcus. “How Can Emerging Powers Speak? On Theorists, Native Informants and Quasi-Officials in International Relations Discourse.” Third World Quarterly 36 (2015): 637–53.

———. “Revisiting the ‘American Social Science’ - Mapping the Geography of International Relations.” International Studies Perspectives 16 (2015): 246–69.

———. “The South in ‘Global IR’: Worlding Beyond the ‘Non-West’ in the Case of Brazil.” International Studies Perspectives 22 (2021): 218–39.

Lohaus, Mathis, and Wiebke Wemheuer-Vogelaar. “Who Publishes Where? Exploring the Geographic Diversity of Global IR Journals.” International Studies Review 23, no. 3 (2021): 645–69.

Lohaus, Mathis, Wiebke Wemheuer-Vogelaar, and Olivia Ding. “Bifurcated Core, Diverse Scholarship: IR Research in 17 Journals around the World.” Global Studies Quarterly 1, no. 4 (2021). doi: 10.1093/isagsq/ksab033.

Makarychev, Andrey, and Viatcheslav Morozov. “Is ‘Non-Western Theory’ Possible? The Idea of Multipolarity and the Trap of Epistemological Relativism in Russian IR.” International Studies Review 15 (2013): 328–50.

Maliniak, Daniel, Amy Oakes, Susan Peterson, and Michael J. Tierney. “International Relations in the US Academy.” International Studies Quarterly 55 (2011): 437–64.

Maliniak, Daniel, Susan Peterson, Ryan Powers & Michael J. Tierney. “Is International Relations a Global Discipline? Hegemony, Insularity, and Diversity in the Field.” Security Studies 27, no. 3 (2018): 448–84.

Mokry, Sabine. “Chinese International Relations (IR) Scholars’ Publishing Practices and Language: The ‘Peaceful Rise’-Debate.” In Globalizing International Relations - Scholarship Amidst Dives and Diversity, edited by Ingo Peters and Wiebke Wemheuer-Vogelaar, 135–63. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Mosbah-Natanson, Sébastien, and Yves Gingras. “The Globalization of Social Sciences? Evidence from a Quantitative Analysis of 30 Years of Production, Collaboration and Citations in the Social Sciences (1980–2009).” Current Sociology 62, no. 5 (2014): 626–46.

Neuman, Stephanie G. International Relations Theory and the Third World. Palgrave Macmillan, 1998.

Noda, Orion. “Epistemic Hegemony: The Western Straitjacket and Post-Colonial Scars in Academic Publishing.” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 63, no. 1 (2020): 1–23.

Picq, Manuela. “Rethinking IR from the Amazon.” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 59 (2016): 1–17.

Puchala, Donald J. “Some Non-Western Perspectives on International Relations.” Journal of Peace Research 34 (1997): 129–34.

Qin, Yaqing, ed. Globalizing IR Theory: Critical Engagement. London: Routledge, 2020.

Risse, Thomas, Frank Havemann, and Wiebke Wemheuer-Vogelaar. “Theory Makes Global IR Hang Together. Lessons from Citation Analysis.” Freie Universität Berlin Repository (2020). doi: 10.17169/refubium-28510.

Shilliam, Robbie. International Relations and Non-Western Thought: Imperialism, Colonialism and Investigations of Global Modernity. London: Taylor & Francis, 2010.

Smith, Steve. “The Discipline of International Relations: Still an American Social Science?” British Journal of Politics and International Relations 2 (2000): 374–402.

Thomas, Caroline, and Peter Wilkin. “Still Waiting after All These Years: ‘The Third World’ on the Periphery of International Relations.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 6 (2004): 241–58.

Tickner, Arlene. “Core, Periphery and (Neo) Imperialist International Relations.” European Journal of International Relations 19 (2013): 627–46.

———. “Latin American IR and the Primacy of Lo Práctico.” International Studies Review 10 (2008): 735–48.

———. “Seeing IR Differently: Notes from the Third World.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 32 (2003): 295–324.

Tickner, Arlene, and Ole Wæver. International Relations Scholarship Around the World. London: Routledge, 2009.

Turton, Helen. International Relations and American Dominance: A Diverse Discipline. London: Routledge, 2015.

———. “Locating a Multifaceted and Stratified Disciplinary ‘Core.’” All Azimuth 9, no. 2 (2020): 177–209.

Turton, Helen, and Lucas Freire. “Peripheral Possibilities: Revealing Originality and Encouraging Dialogue through a Reconsideration of ‘Marginal’ IR Scholarship.” Journal of International Relations and Development 19 (2014): 534–57.

Valbjørn, Morten. “Dialoguing about Dialogues: On the Purpose, Procedure and Product of Dialogues in Inter-National Relations Theory.” International Studies Review 19 (2017): 291–96.

Wæver, Ole. “The Sociology of a Not So International Discipline: American and European Developments in International Relations.” International Organization 52 (1998): 687–727.

Wemheuer-Vogelaar, Wiebke, Nicholas J. Bell, Mariana Navarrete Morales, and Michael J. Tierney. “The IR of the Beholder: Examining Global IR Using the 2014 TRIP Survey.” International Studies Review 18 (2016): 16–32.